Those in the pay of the Emperor in the 16th Century were probably about two-thirds archers, one-third firearm men. As time passed, the proportion of the latter grew, but there were many men with composite bows until long after our period. In the second half of the 16th Century there were two sizes of matchlock firearm, corresponding to the European musket and caliver. The former were described in the mid-17th Century as small but well-finished; they were often inlaid and otherwise decorated, and were kept in scarlet or green cloth covers when not in use. They had wooden forks or rests, which seem to have been hinged to the gun itself, and were perhaps rather short, as Indian musketeers sometimes sat or squatted to fire.

The infantry were far inferior in status and morale to the cavalry, and spent much of their time on the more menial duties of sentry-go and baggage-guard. In battle, like the cavalry, they kept no order, and either skirmished or were found defending laagers or field-fortifications.

The firearm men did not use the European bandolier, but wore waist-belts, often decorated, from which hung match, flint and steel, bullet pouches, powder flask and priming-horn.

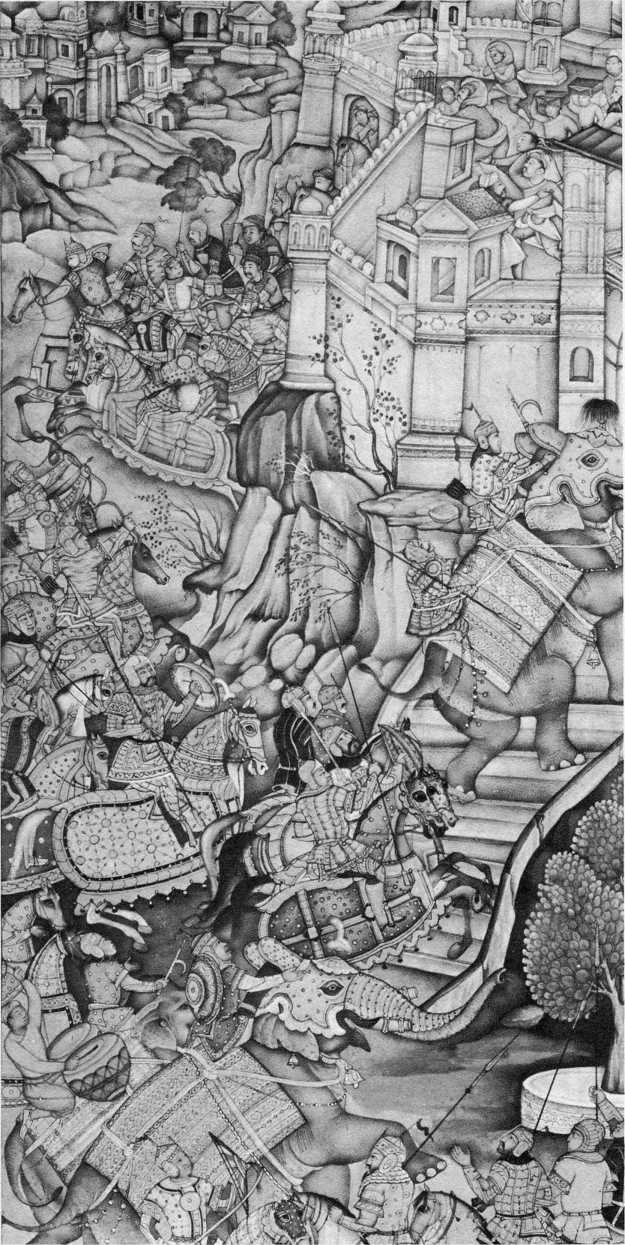

Moghuls. Shows heavy cavalry, elephants (note armour, including upstanding ‘ears’ to protect driver) (The British Library).

In addition to the firearms mentioned, there were also heavier ‘jezails’ like the wall-pieces used in Europe; they were indeed often so mounted in fortresses, but were also taken into the field on camel mountings. In the mid-17th Century the army included 300 camels so equipped.

Apart from the paid infantry and cavalry mentioned, Moghul armies normally contained vast hordes of local levies and militia, hired tribesmen, followers of local Rajahs and so forth. These would provide, chiefly, light cavalry and infantry, the latter being armed with bamboo spears, sword and shield, sling or bow. (Some tribesmen still used bamboo longbows as in Alexander's day.)

Such troops largely served to satisfy the Indian passion for numbers, and were normally useless, or even harmful, to their own side, both in battle and on the march, when, together with the invariable vast crowds of camp-followers and massive paraphernalia of the Emperor’s camp and elephant-borne harem, they helped to slow down the army to the crawling pace which so irritated contemporary European observers like Sir Thomas Roe.

World History

World History