Most medieval kings were itinerant. They did not reside for long periods in one place or govern from fixed capital cities, but journeyed continually from place to place. There were several reasons for this. Economically, it might be cheaper and more convenient to move the king, his retinue and their horses to the supplies of food, drink and fodder rather than vice versa. The itinerant court thus consumed the produce of royal manors or received 'hospitality' from bishops, abbots or others on whom the obligation lay, before moving on to its next source of sustenance. Obviously, as the European economy became more monetized and commercialized, such an economic rationale for itinerant kingship grew less pressing: market solutions were now available to meet the problem of supply. There were also political advantages to itineration, however. In an age of low rates of literacy, when local bureaucracies were rudimentary or nonexistent, the physical presence of the king was the surest way of making royal authority a reality. Medieval government, it has been said, was 'a government of the roadside'.

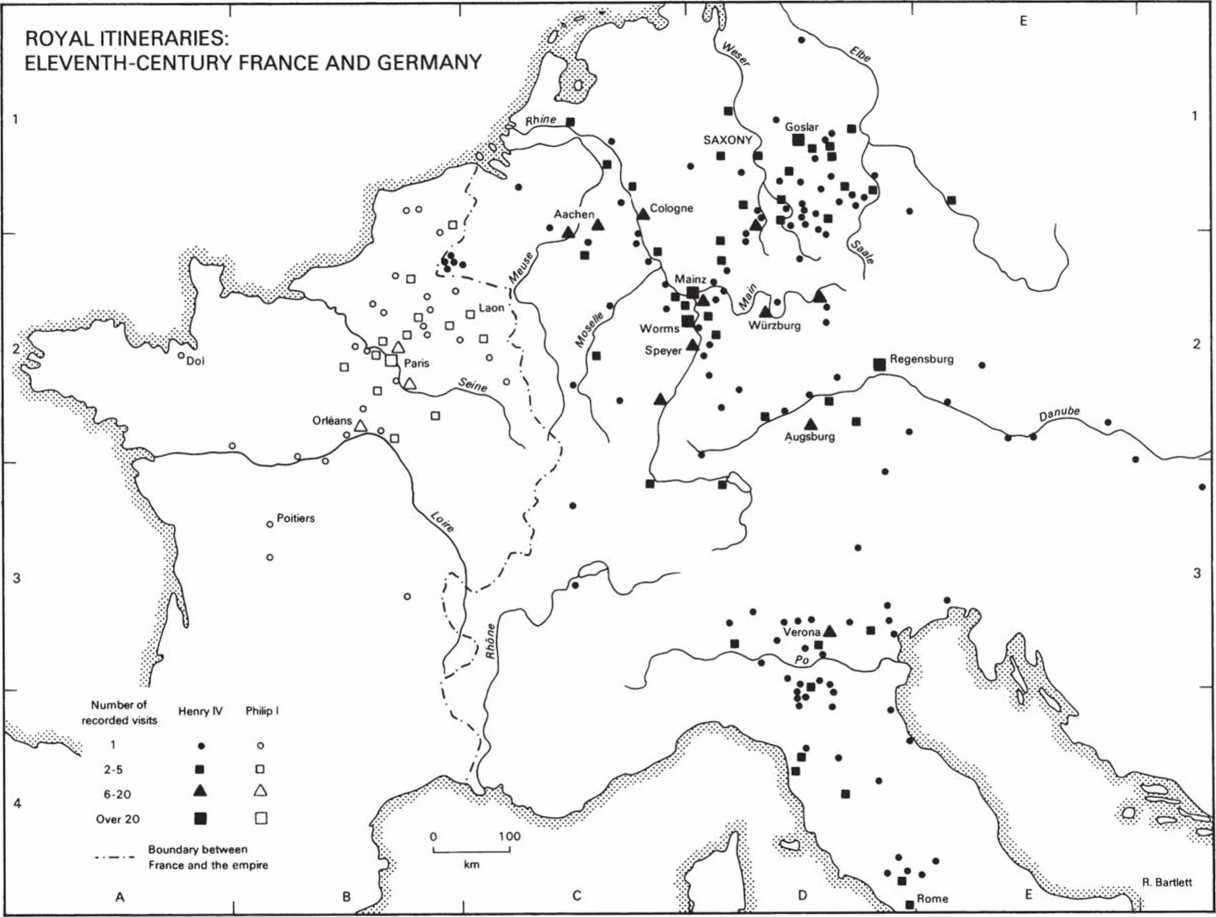

The map shows the places visited during their long reigns by two contemporary rulers, Philip I of France (1060-1108) and Henry IV of Germany (1056-1106), as they are revealed by contemporary documents. Both kings were constantly on the move, but the patterns of their itineraries show significant variation. First, much more is known about the movements of Henry IV than Philip I, partly because the number of royal documents from the German king's reign is much greater than that from the French king's (491:171), partly because Henry was a controversial figure and excited the chroniclers' attention. Also clearly visible is the fact that the German kings of the eleventh century acted on a far vaster scale than their French contemporaries. Henry moved regularly throughout Germany, was deeply involved in Italy and campaigned south of Rome, east of Austria and north of the Meuse. The extreme limits of his journeyings produce an axis of around 1,500 km. Not all of this was happy: the concentrations of activity in Saxony and north Italy represent prolonged attempts to subdue opposition. Nevertheless, the

Geographical range of Henry IV's activities indicate the ambitious scope of the German monarchy.

In contrast, the Capetian king was limited to a relatively small area, especially the zone between the three main royal centres of Orleans, Paris and Laon. Outside this region the king travelled almost as a foreign prince in his own kingdom. His visits to Poitiers and Dol, for example, which took place in 1076, were to seek a military alliance with the duke of Aquitaine and to relieve a castle besieged by William, duke of Normandy—he was treating with equals or enemies rather than subjects. The virtual autonomy of the great French princes in the eleventh century, compared with the relatively greater subordination of the German dukes to royal authority, is reflected in the itineraries of the two kings.

The map demonstrates the basic geographical pattern of royal power in the two kingdoms: in France a royal demesne in the Ile-de-France which was the only real arena for Capetian power; in Germany a monarchy deeply embedded in the Rhine valley and south-east Saxony (the homelands, respectively, of the Salian dynasty and their predecessors, the Ottonians), but which sought also to maintain a hold over the Po valley and Rome. Within two centuries these patterns would be fundamentally altered as the Capetians extended their power beyond the Ile-de-France while the German monarchy saw its lands and powers disintegrate.

R. Bartlett

World History

World History