There were in several respects two ‘economies’ in the Roman world. On the one hand, there was the economy of the state and government, representing a fairly straightforward relationship between producers, taxation, and the redistribution of the

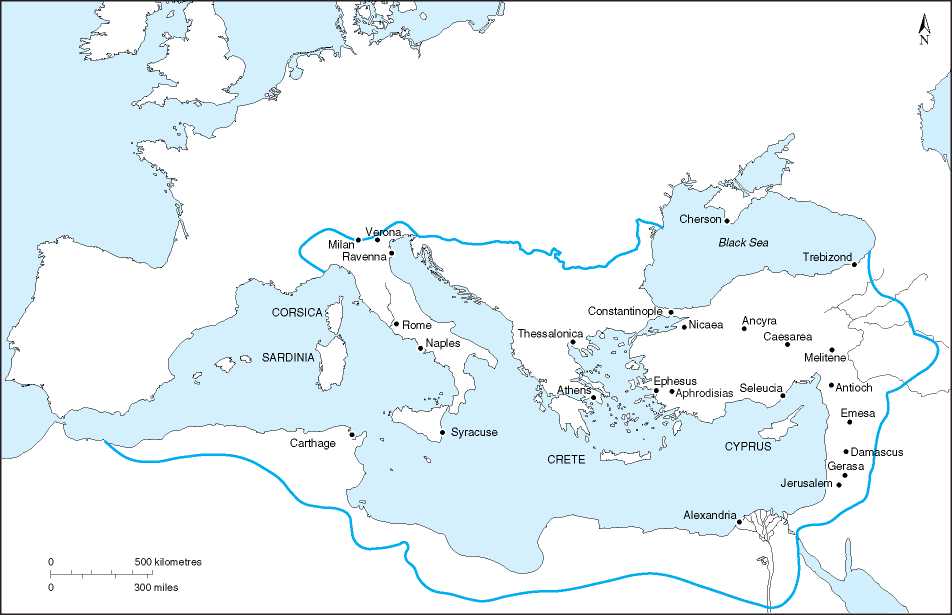

Map 3.4 Major cities of the 6th century.

Resources thus extracted to the army, court, government and civil administration. The coinage issued by the government through its mints facilitated the smooth operation of this system. On the other hand, there was the ‘economy’ of ordinary society, a vast web of intersecting pools of activity and resources tying town to countryside and vice versa, pools of activity that sucked in the state’s coinage and circulated it around entirely different patterns of transaction and exchange from those of the state’s fiscal system. Both were inter-related, yet both were in several respects autonomous, operating on different principles and responding to substantial shifts in context and circumstance in very different ways.

Long-distance trade displayed particular patterns that reflected the prosperity of the regions where certain goods were produced. Oil and grain were exported, along with the pottery in which they were transported, from North Africa throughout the Mediterranean world; oil and wine travelled from Syria to the western Aegean and south Balkan coastlands, whence they were re-exported inland or further west - to Italy and southern Gaul. The distribution of ceramic types provides much information about these movements: many types of produce were carried in pottery containers of one sort or another - amphorae, for example, often very large vessels, were used for transporting and storing liquids such as wine and oil, as well as solids such as grains, the shape varying according to need. They were moved around chiefly by sea, and were often accompanied by other ceramic products, including fine tablewares, which were exported alongside the bulk goods. Finds of such pottery, in conjunction with knowledge of their centres of production, offer a fairly detailed picture of such trade in this period. Some of these goods travelled considerable distances - in the later sixth century ships were still sailing from Egypt into the Atlantic and around to south-west England, trading corn for tin. This Mediterranean trade did not reflect private, market-led demand alone: much of the commerce in fine wares travelled in the ships of the great grain convoys from North Africa to Italy and from Egypt to Constantinople, the captains of the ships being permitted to carry a certain quantity of goods on their own account for private sale in return for a percentage of the price obtained.

A marked difference existed between those centres of population and production with access to the sea, and inland towns and villages. The economy of the late Roman world was intensely local and regionalised, and this was reflected also in the attitudes and outlook of most of the population: the expense of transport, especially by land, meant that patterns of settlement and the demographic structure of the empire conformed to the limits of the resources that were locally available. And here, it was chiefly the major urban centres that were involved.

Pottery is crucial in revealing patterns of production, exchange and consumption in the late Roman world. Indicative of the strongly market-orientated nature of estate and smallholder production in North Africa, for example, is the fact that until the late fifth and early sixth century imports from this region were strongly represented throughout the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean regions. Commerce and exchange seem in no way

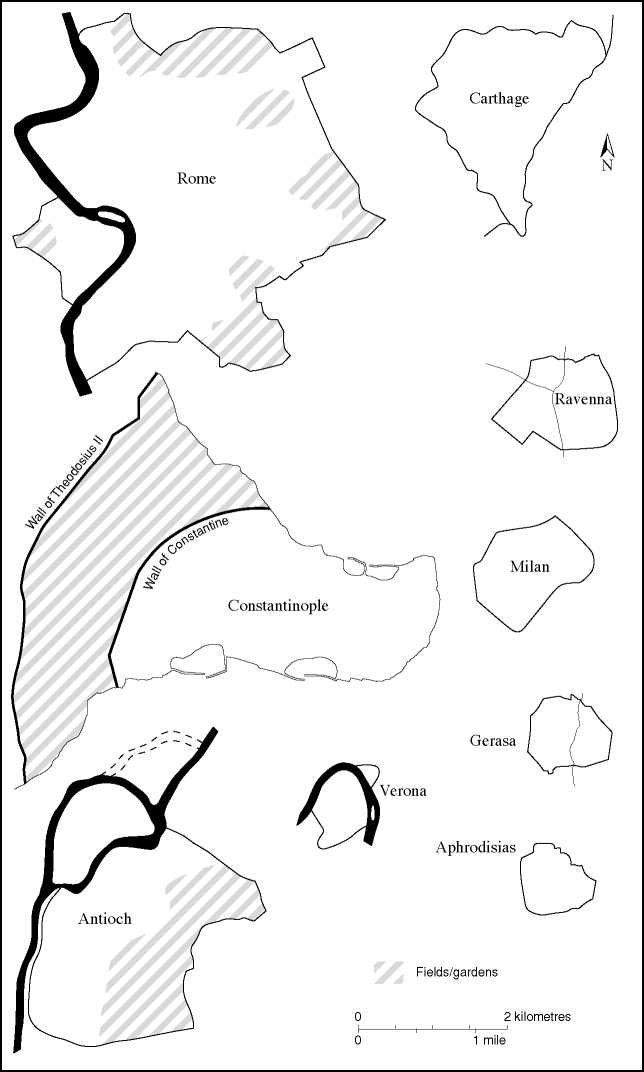

Figure 3.3 Comparative size of walled towns in the eastern Roman empire, 5th-7th centuries.

To have been hindered by the political boundaries of the period. From the later fifth century, there was a reduction in regional North African ceramic production, a reduction in the variety and sometimes the quality of forms and types, especially of amphorae, and a corresponding increase of eastern exports to the west. African imports to the east Mediterranean, both fine and coarse wares, decline sharply from about 480-490 on, to

Achieve a limited recovery after Justinian’s destruction of the Vandal kingdom in the 530s. The incidence of wares produced in the Aegean region and connected with the development of Constantinople as an imperial centre during the fourth century increases in proportion as that of African wares decreases; while over the same period the importance of imported fine wares from the Middle East, especially Syria and Cilicia, also

|

T—r | ||

|

_S | ||

|

Ur | ||

O o o

M

|

NTT | ||

|

» 0-rO-Ttn |

I I I I I I ITT

World History

World History