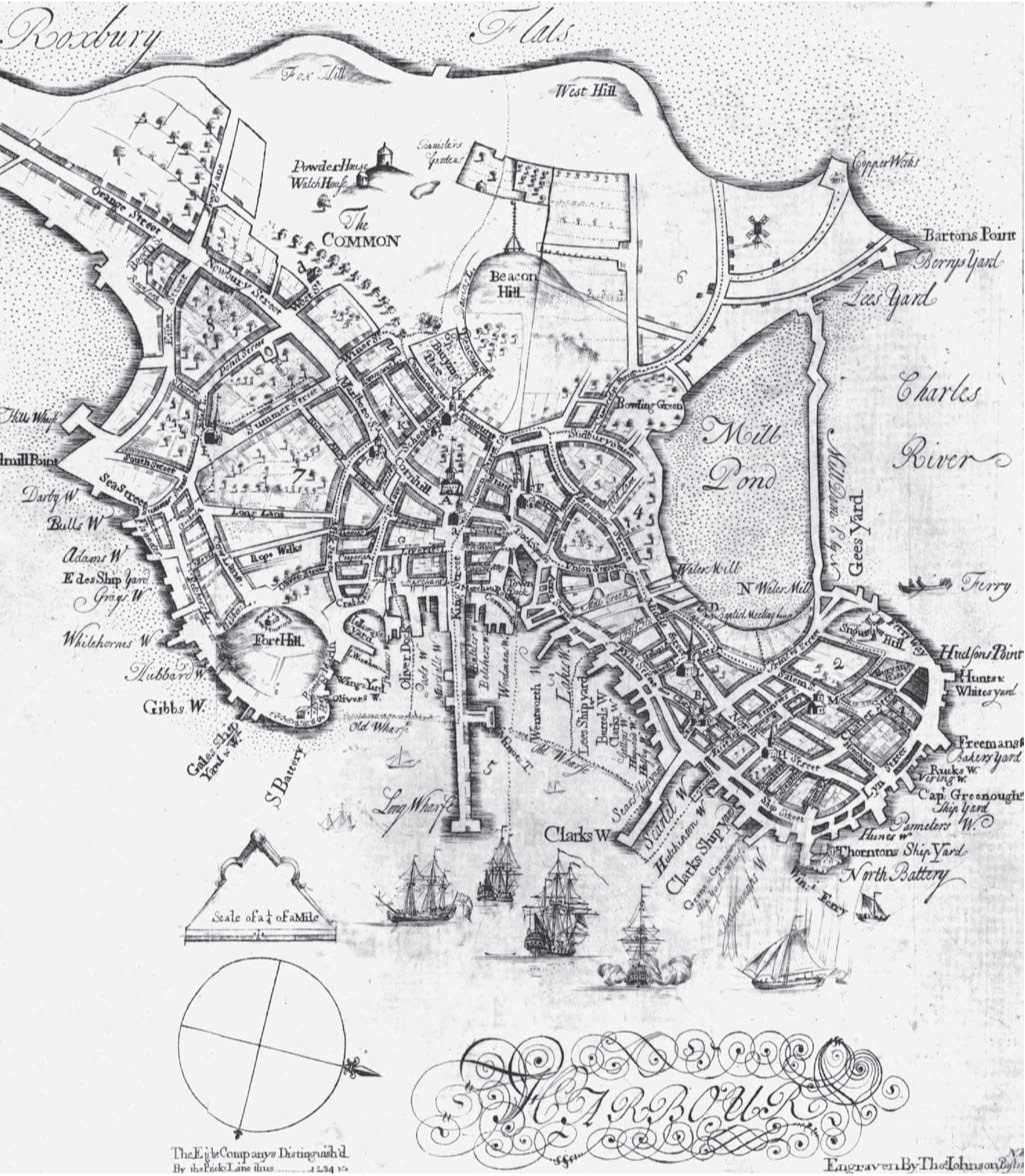

Boston’s location on the Shawmut Peninsula, with three lofty hills (the Tremont or Tri-mountain), natural springs, and a deep and protected harbor, was a natural choice for the first wave of Puritan settlers to Massachusetts, who arrived in 1630. The Puritans envisioned themselves as establishing a “city on a hill,” and here was the hill. They were invited from Charleston by the Reverend William Blackstone, a hermit who had been living on the peninsula since 1625.

The town of Boston was founded in September 1630 as the capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Its form of government was created in 1633 as the town meeting with elected selectmen, and it lasted until Boston was incorporated as a city in 1822. Early Massachusetts governors John Winthrop and Henry Vane and the leading Puritan ministers John Wilson and John Cotton resided in Boston. The Boston Common was established as the common pasturage in 1632, and the town market was created in 1634. Harvard College was established in neighboring Cambridge across the Charles River in 1636. Boston’s population swelled quickly to nearly 1,700 in the first decade, then slowed as immigration declined.

Trade dramatically affected Boston’s character after the disruption of the English Civil War of the 1640s, transforming the town into one of the most important shipping ports in the British Empire. Shipping was based heavily on the export of timber, cod, and rum and the import of wine, wheat, molasses, and finished materials. Shipbuilding flourished as the need for ships grew.

The city’s merchants diversified their operations, taking a lead in the African slave trade and dealing directly with smugglers and privateers. Merchants largely ignored the Navigation Acts, resulting in Boston, profiting as a commercial center.

An entrenched elite of several families developed, they provided leadership to the town and the colony from Boston. Leaders from among the Winthrop, Saltonstall, and Sewall families, with popular support, were responsible for arresting Royal Governor Sir Edmund Andros and his associates in 1688, imprisoning him on an island in Boston Harbor. They hoped for the return of the godly Puritan Commonwealth, but the Second Charter of 1691, a compromise achieved by Increase Mather, extended sullrage to non-Puritans by eliminating church membership as a requirement for franchise status and created a royal governor appointed by the king.

A series of fires, especially the major ones in 1676 and 1711, consumed large portions of the town’s center. Boston quickly recovered each time, aided by legislation requiring brick for new structures in town. This spurred construction of some of the most impressive buildings in the colonies: the Old Brick Church and Old State House between 1711 and 1713, Christ Church (the Old North Church) in 1723, and the Old South Meetinghouse in 1729 (all of which, except for the Old Brick, are still standing). Roads were graded for drainage, paved with cobblestones, and routinely cleaned. Subterranean drainage was created in 420 sections between 1708 and 1720. The most important construction project was Long Wharf in 1711. It extended from King Street nearly a mile into Boston Harbor, making it one of the largest in the world.

By 1720 Boston was the largest British port in North America, with a population close to 12,000. It exerted its cultural and stylistic influence across New England and to the other colonies. Printing and book selling, painting and engraving, goldsmithing and cabinet making were just some of the advanced, specialized trades that flourished in Boston. The bustling town was the home of leading theologians, political aspirants, and a mercantile elite, as well as laborers, mechanics, housewives, prostitutes, slaves, transient seamen, and even the young Benjamin Franklin.

As Boston approached its highest pre-Revolutionary population, more than 16,000, a major economic depression in the 1740s combined with increasing poverty, smallpox epidemics, and deaths resulting from the continual warfare with France. Boston entered a period of declining shipping, decreasing population, and civil unrest. Wealth inequalities increased dramatically. Crowds of people often took to the streets to advocate their own political agendas. The vocally political nature of Bostonians of all classes from the 1740s

To the 1770s gave rise to various discontents and was a vital ingredient to the start of the American Revolution.

And cultural center, rivaled only by Philadelphia and New York City.

See also Endecott, John; Knight, Sarah Kemble; Mather, Cotton; Sewall, Samuel.

This 1728 map shows Boston when it was still the largest city in the thirteen colonies. (Library of Congress)

Further reading: Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979); Walter Muir Whitehill, Boston: Topographical History, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000).

—Stephen C. O’Neill

World History

World History