The name given by the Norse to territory in the modern-day Maritime Provinces of Canada, where they arrived around the year 1000 and established a settlement, the first European outpost in the Western Hemisphere.

According to a Norse saga written perhaps 200 years later, sometime around the turn of the first Christian millennium Leif Eriksson, who was himself the son of the famous Norse explorer Erik the Red, set sail from Greenland to lands lying farther west. He encountered and named three places: Helluland (“Slab-Land”), Markland (“Forest Land”), and Vinland (“Wineland”). A later Norse explorer named Thorfinn Thordsson Karlsefni and his wife, Gudrid, followed up Leif’s efforts and took a small contingent to Vinland in the hope of establishing a colony. Although they had a baby while on their expedition, within a year they returned to Greenland and eventually to Norway before they made a permanent home in Iceland. In the late 12th century a Norse bishop named Erik Upsi also set sail for Vinland, although no record exists to tell what happened.

In the late 20th century archaeologists working at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland found evidence of an 11th-century Norse settlement, probably Vinland; others have speculated that Markland was present-day Labrador.

Further reading: Alfred Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); William W. Fitzhugh and Elisabeth I. Ward, eds., Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga (Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000); Kirsten Seaver, The Frozen Echo: Greenland and the Exploration of North America, ca. A. D. 1000-1500 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1996); The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America, trans. Magnus Magnusson and Herman Palsson (Harmondsworth, U. K.: Penguin, 1965).

Vitoria, Francisco de (ca. 1485-1546) scholar Francisco de Vitoria, an influential Spanish jurist and professor of theology, argued that the native peoples of the Americas had a legitimate right to the ownership and governance of their own lands.

In 1539 Vitoria entered into a long-standing debate with the publication of his treatise “On the American Indians” (“De Indis”). While most Spaniards accepted the legitimacy of the Spanish conquest of America, some voices, most notably that of the Dominican priest Bartolome DE Las Casas, condemned the cruelty of the Spanish. In 1511 another Dominican, Anton de Montesinos, warned the Spanish settlers of Hispaniola that if they did not stop treating the Indians cruelly, they would be damned to hell. Neither Las Casas nor Montesinos doubted that the Spanish had a legitimate claim to the New World, but they believed that the Indians should be treated more fairly.

The mistreatment of the Indians helped sustain a debate in Europe over the justice of the Spanish conquest. In 1510 John Mair, a Scottish theologian teaching in Paris, maintained that the conquest of the Americas was just because the Indians were “natural slaves” who would benefit from European rule. As “natural slaves,” the Indians needed Europeans to guide them and introduce them to Christianity. If the Natives of the New World had to be conquered before they would accept Christianity, then war against the Indians was just. The Spanish lawyer and adviser to the Crown Juan Lopez de Palacios Rubios also argued that the Spanish conquest of the New World was legitimate. For Palacios Rubios, the Catholic Church had dominion over the entire world. In the Treaty of Tordesillas, Pope Alexander VI had granted authority over the New World to the Spanish. As long as the Indians refused to become Christian, they were in rebellion against the church and could rightfully be subjugated.

Vitoria rejected these arguments. The Indians, he wrote, were rational human beings, not the “natural slaves” that Aristotle had suggested must exist. As rational beings, the Indians had a right to their lands and goods, and the Spanish had no right to take their property or enslave them. Their own rulers, not the Spanish, had legitimate authority over them. Vitoria also maintained that the pope’s authority was purely in the spiritual world. Because he lacked power in the temporal world, he could not take the Indians’ territories away and give them to one European prince or another. Furthermore, conquest of the Indians could not be justified by the desire to convert them to Christianity. Spanish treatment of the Indians thus far, Vitoria argued, was so cruel as to make the Indians less likely to convert.

The Indians’ right to their land was not inviolable, however. Like other Catholics of the day, Vitoria believed that the pope’s spiritual (though not temporal) authority extended across the world. The pope, therefore, could declare that only one European power had the right to colonize the New World in the interest of peacefully promoting the conversion of the Indians to Christianity. The Spanish could not compel the Indians to convert, but the Indians had no right to refuse to allow missionaries to travel and preach in their lands. Vitoria also argued that individuals and peoples had a right to trade with one another to their mutual benefit. If the Indians refused to permit missionaries to live among them or did not allow trade, then the Spanish could legitimately make war upon them.

Although Vitoria’s arguments did allow for a “just war” to be undertaken against the Indians, their significance lay in his insistence that the Indians were rational human beings with a legitimate claim to their lands and freedoms. The arguments made by Vitoria, Las Casas, and other scholars and theologians helped lead to the Emperor Charles V’s issuance of the New Laws of 1542. These laws declared that the Indians were vassals of the Crown and defended their rights to self-preservation, property, and justice against Spanish crimes.

Further reading: Suzanne Hiles Burkholder, “Vitoria, Francisco de,” in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 5, ed. Barbara A. Tenenbaum (New York: Scribner’s, 1996), 429; Anthony Pagden, The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1982);-, Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire

In Spain, Britain and France, c. 1500-c.1800 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1995); “Vitoria on the Justice of Conquest,” in The Conquerors and the Conquered, vol. 10, New Iberian World: A Documentary History of the Discovery and Settlement of Latin America to the Early 17th Century, eds. John H. Parry and Robert G. Keith (New York: Times Books, 1984), 290-323.

—Martha K. Robinson

Waldseemuller, Martin (ca. 1470-ca. 1518-1521) geographer

Martin Waldseemuller, a German artist and cartographer, was the first to use the term America to refer to the New World.

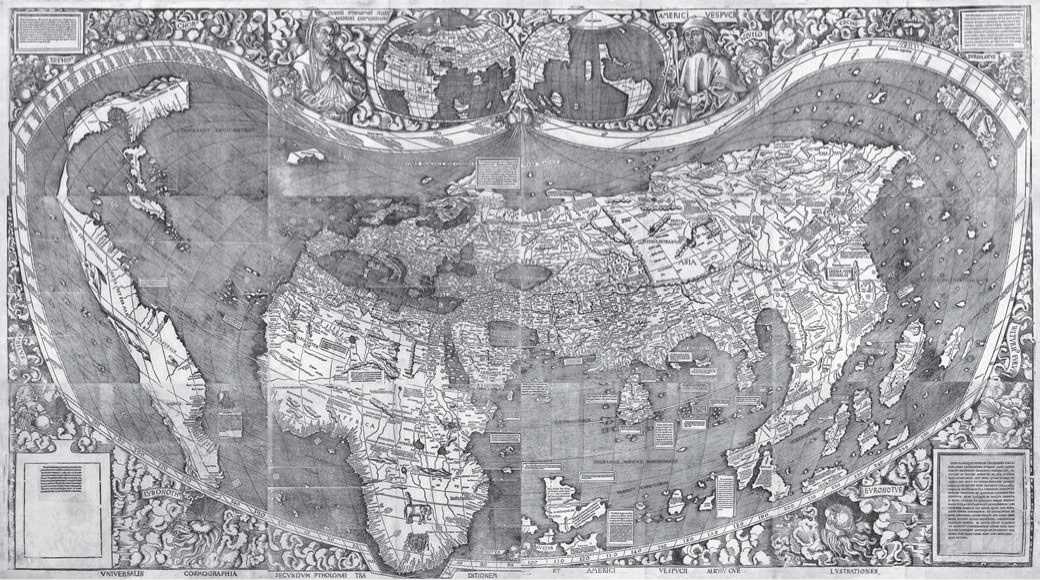

Waldseemuller was born in Germany but lived in northeastern France. His most important map of the Western Hemisphere, the Universalis cosmographia (1507), was probably commissioned by the duke of Lorraine. This map, almost 10 feet square, was printed from 12 wood blocks and was so popular that 1,000 copies were made, only one of which has survived. The Universalis cosmographia drew on Portuguese and Italian maps and on Amerigo Vespucci’s account of his travels (see Documents). Unlike other maps of the day, which portrayed North America as an extension of Asia, on Waldseemuller’s map North America appeared as a relatively small but distinct landmass.

In his Cosmographia introductio (1507), Waldseemuller wrote that because Amerigo Vespucci had discovered a fourth continent, it should bear his name. “I do not see,” he wrote “why anyone should rightly forbid naming it Amerige—land of Americus, as it were, after its discoverer

The Universalis cosmographia (1507), by Martin Waldseemuller (Library of Congress)

Americus, a man of acute genius—or America, since both Europe and Asia have received their names from women.” Waldseemuller and later cartographers used the term America to refer only to South America. Until 1538, when Gerhardus Mercator labeled the northern continent America, most cartographers called it Terra de Cuba, Terra Florida, Terra del Labrador, or Parais.

Waldseemuller also wrote several books and made a globe and a large-scale map of Europe. His works influenced other 16th-century cartographers and were widely imitated.

Further reading: Seymour I. Schwartz and Ralph E. Ehrenberg, The Mapping of America, (New York: Abrams, 1980); R. V. Tooley, Maps and Map-Makers (London: B. T. Batsford, 1987); Hans Wolff, “Martin Waldseemuller: The Most Important Cosmographer in a Period of Dramatic Scientific Change,” in Hans Wolff, ed., America: Early Maps of the New World (Munich: Prestel, 1992).

—Martha K. Robinson

Walsingham, Sir Francis (1530?-1590) statesman An English statesman and diplomat who served for almost two decades as Queen Elizabeth I’s secretary of state.

Early in his career Walsingham left England when Queen Mary I acceded to the throne, remaining abroad until her reign ceased. His five-year sojourn fostered his Protestant zeal and also helped develop his diplomatic career. While abroad he gained information in Spain, Italy, and France, all of it useful when he returned to England when Elizabeth took the throne.

Walsingham became one of the Queen’s most trustworthy administrators. His first official task placed him in charge of London’s secret service, through which he rooted out nefarious internal and external plots against the monarch. In August 1568, for example, he was able to produce for Lord Burghley (another close ally of the Queen) a list of all persons entering Italy during the previous three months who were hostile toward Elizabeth.

In 1570 Walsingham traveled to Paris on his first officially state-sponsored diplomatic mission. He hoped to establish better relations between England and an increasingly Huguenot influenced France. Rising hostilities between French Huguenots and Catholics, culminating in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, cut Walsingham’s efforts short. He returned to England in 1573 with little optimism about future relations between France and England. Upon his return Walsingham became secretary of state, a post he held for the next 17 years. Working with Machiavellian precision both at home and abroad, he trained his attention on Catholic zealots. For his efforts Elizabeth knighted him in 1577.

As part of his foreign policy strategy, Walsingham endorsed maritime ventures and colonial expansion. He corresponded with Ralph Lane, Sir Richard Grenville, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert. In addition, he served as a patron to all of England’s chief writers on the exploration of the New World, including Richard Hakluyt the Younger. In 1587 Walsingham’s spy network supplied him with the numbers of men, characteristics of vessels in commission, and full inventories of horses, armor, ammunition, food, and supplies of the heralded Spanish Armada. However, a year later his connections dissolved, leaving him with little information prior to England’s upcoming naval confrontation with the armada.

Walsingham died in 1590 after facing pecuniary difficulties toward the end of his life. Living during an age in which the traitor, the conspirator, the spy, the counterspy, and the agent-provocateur appeared within the shadows of the larger backdrop of international diplomacy, he proved the consummate late 16th-century statesman and diplomat.

Further reading: John Bossy, Giordano Bruno and the Embassy Affair (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991); Conyers Read, Mr Secretary Walsingham and the Policy of Queen Elizabeth (New York: AMS Press, 1978).

—Matt Lindaman

Wanchese (fl. 1580s) Roanoke diplomat One of two Indians brought to England from the islands of present-day North Carolina in 1584, Wanchese, a Roanoke Indian, learned to speak English but rejected the colonists upon returning to America.

Wanchese and Manteo arrived in England with Arthur Barlowe and Philip Amadas, who had explored the coast of North America in search of a place to build a colony. While in England the two Indians lived with Sir Walter Ralegh. While Manteo was a man of high status among his people, Wanchese seems to have ranked less high among his, and Manteo likely treated him as an inferior. He may have been sent to England by Wingina, a Roanoke leader, to learn about the English. When he returned to America in 1585, he left the colonists and returned to his own people. He apparently reported that the English were only men and did not have supernatural powers. The colonists, who believed that any reasonable human would acknowledge English superiority, regarded him as something of a traitor for preferring his own people. They also believed that he tried to convince Wingina to conspire against the colony.

Further reading: Thomas Harriot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590; reprint,

New York: Dover Publications, 1972); Karen Ordahl Kup-perman, Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America (Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press, 2000);-, Roa

Noke: The Abandoned Colony (Totowa, N. J.: Rowman & Allanheld, 1984); David Beers Quinn, Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584-1606 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

—Martha K. Robinson

World History

World History