Designed to provide relief for homeowners facing foreclosure and to rescue the mortgage industry, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created during the first Hundred Days of the New Deal.

The Great Depression had created grave troubles in the mortgage industry. Prior to the 1930s, mortgage loans typically required high down payments (typically 35 percent or more) and had terms of five to 10 years, with a large “balloon” payment at the end of the loan. As homeowners were increasingly unable to meet the balloon payment, they had to refinance the loan or face foreclosure. To meet their own debts, banks called in balloon payments and liquidated the mortgages. Foreclosures jumped from 150,000 in 1930 to 250,000 in 1932, and to 1,000 per day by early 1933. With banks needing liquid assets and no home insurance to protect the owners, the mortgage industry was in shambles.

President Herbert C. Hoover had tried to address the problem with the Federal Home Loan Bank Act in 1932. Congress, however, weakened Hoover’s proposal to allow homeowners to use their home as collateral for a refinancing loan by making the amount of collateral needed to secure the loan more than most homeowners could afford. The result was that the Federal Home Loan Banks proved unable to slow the rate of foreclosure. Faced with an accelerated number of home (and farm) foreclosures after his inauguration, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the Home Owners Refinancing Act in the spring of 1933; the act passed Congress in June 1933, creating the Home Owners Loan Corporation. (The Farm Credit Administration was also created in June to refinance farm mortgages.)

The HOLC had two purposes. First, it provided help to homeowners in danger of losing their homes by refinancing their mortgages. Second, it assisted troubled banks holding the mortgages by insuring the loans, thus allowing the banks to liquefy defaulted mortgages rather than owning and trying to resell the homes themselves. Operating mostly in America’s cities, the HOLC refinanced almost one out of every five mortgages during the agency’s life. Just from 1933 to 1936, it spent some $3 billion and refinanced a million homes. But while the agency assisted with refinancing, it was really an insurance agency for banks, not for homeowners, and it also foreclosed on properties, especially during the recession OF 1937-1938, when it foreclosed on 100,000 homes.

The Home Owners Loan Corporation did not survive World War II. It was a victim of Congress’s budget-cutting in 1943, when many New Deal relief agencies, such as the Works Progress Administration and National Youth Administration, were eliminated. But the HOLC left a lasting legacy on the mortgage industry. Together with other New Deal housing programs, such as the Federal Housing Administration and the Federal National Mortgage Association (known popularly as Fannie Mae), HOLC helped to stabilize and rationalize the mortgage process. Mortgage loans became more affordable for many more Americans, the appraisal of homes was standardized so that insured banks financed homes at their appropriate value, and banks were able to turn their mortgages into liquid assets quickly by reselling them for their current value. By 1945, the risk that had long been a part of the realty and home construction industry had largely been removed, greatly aiding in the home building explosion of the postwar period.

Further reading: Kenneth T. Jackson, “Race, Ethnicity, and Real Estate Appraisal: The Home Owners Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration,” Journal of Urban History 6:4 (1980): 419-452; Gail Radford, Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

—Katherine Liapis Segrue

Hoover, Herbert C. (1874-1964) 31st U. S. president Herbert Clark Hoover served from 1929 to 1933 as the 31st president of the United States. Following impressive successes in business and government, Hoover won an overwhelming majority in the presidential election of 1928. But as the Hoover presidency was barely under way, the Great Depression struck, and Hoover’s unsuccessful efforts to revive the economy and deal with unemployment led to his landslide defeat in the election of 1932.

Hoover was born on August 10, 1874, in the Quaker community of West Branch, Iowa. Orphaned at the age of nine, he went to live with the Minthorn family in Newberg, Oregon. In 1891, Hoover entered Stanford University as a member of the “pioneer class” and pursued an interest in engineering. After graduating in 1895 with a degree in geology, he went to work for several mining operations throughout the West. He married fellow Stanford geology major Lou Henry, an outgoing woman who compensated for some of Hoover’s introverted reserve.

In 1897, Hoover took a position with the London-based mining firm Bewick, Moreing and Company. By 1902, he had become a partner in Bewick Moreing, and for the next five years he traveled throughout the world, developing international prominence as an entrepreneur and geologist and earning praise as “the great engineer.” After leaving the firm in 1908, Hoover invested in a number of successful mining and oil ventures. By 1910, at the age of 36, Hoover had amassed a fortune estimated at $3 million.

Hoover’s Quaker upbringing had instilled in him not only an optimism that society could be improved and ordered through cooperative efforts, but also a conviction that wealth brought an obligation to work toward such goals through public service. With the outbreak of World War I, Hoover was given several opportunities to pursue his interest in humanitarianism and to apply his managerial skills to large-scale public endeavors. He headed the international committee for the relief of Belgium, which was successful in feeding 11 million people in Belgium and northern France. President Wilson then appointed Hoover as U. S. food administrator to coordinate efforts to provide food for allies. As food administrator, Hoover sought to avoid rationing, and instead encouraged Americans to voluntarily help conserve food by observing “wheatless” and “meatless” meals. After the war, Hoover headed the American Relief Administration’s European Children’s Fund, which continued to feed children through the summer of 1922.

Hailed as “the great humanitarian” for his wartime efforts, Hoover was appointed Secretary of Commerce under President Warren G. Harding. Although a member of the Republican Party, ideologically Hoover was a progressive, and his appointment prompted opposition within the GOP. Hoover believed, as he described in his 1922 essay “American Individualism,” that the government should play an active role in coordinating private industry and promoting voluntary associational efforts that would improve the overall standard of living without crossing the boundary between the public and private sectors.

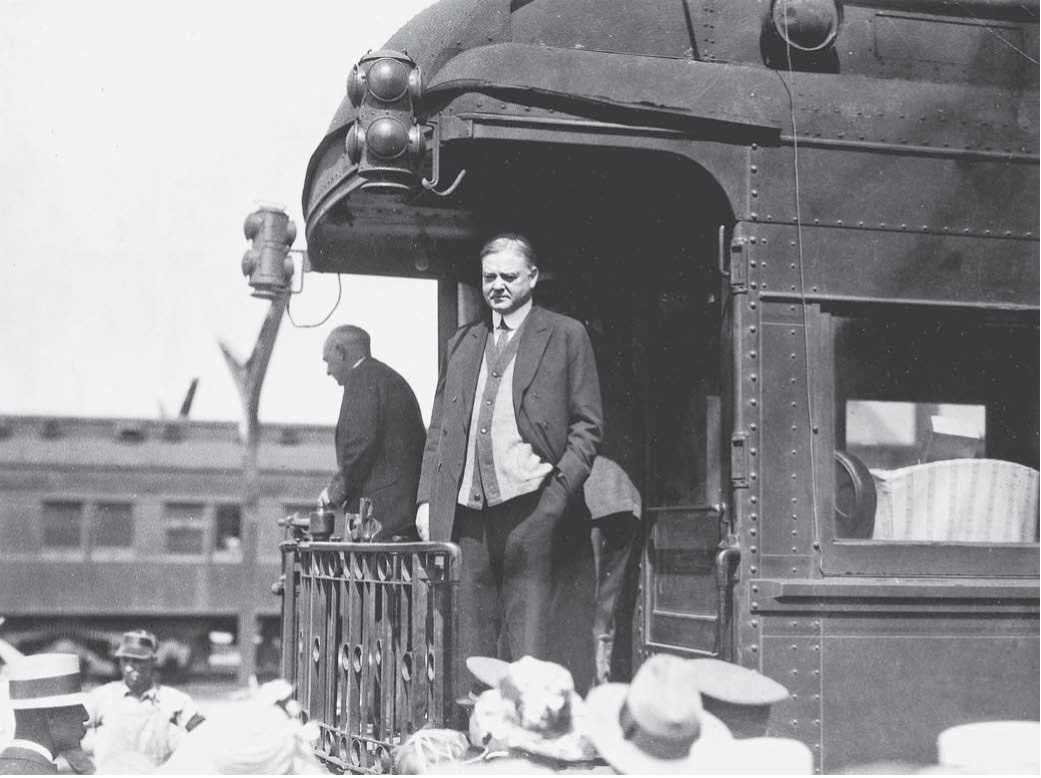

Herbert Hoover campaigning from the back of a railroad car during the 1928 U. S. presidential election (Library of Congress)

During his time as secretary of commerce, he transformed an insignificant department into one of the most important in the executive branch. Hoover not only made efforts to open foreign markets for U. S. goods, but he also worked to promote efficiency throughout the private sector through the standardization of consumer items, the reduction of costly labor strikes, and the improvement of planning processes. Moreover, Hoover worked to develop projects for the irrigation of dry lands and flood control.

In 1928, after President Calvin Coolidge chose not to run for reelection, the GOP turned to its most capable administrator to maintain control of the White House. Receiving 58 percent of the popular vote and carrying 40 out of 48 states, Hoover won by one of the largest margins in history. But with the stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, Hoover’s presidency encountered enormous economic and political difficulties and his reputation sank with the economy. Although Hoover made efforts to stave off further economic decline and to encourage business confidence, including the creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, his failure to take effective action to alleviate unemployment and provide adequate relief led many to perceive him as inept and uncaring. Hoover’s presidency ended with his overwhelming defeat at the hands of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932.

In 1933, Hoover returned to his home in Palo Alto, California, but he never completely retired from public life. Although he wanted the 1936 GOP presidential nomination, the party turned instead to Kansas governor Alfred M. Landon. Hoover remained an outspoken critic of the New Deal, characterizing several programs as “fascistic,” and vehemently criticizing Roosevelt’s 1937 court-PAcking plan. He generally sided with isolationists who criticized Roosevelt’s increasingly interventionist foreign

POLICY in the late 1930s and early 1940s, although he did not join the America First Committee.

During World War II, Hoover established the privately run Polish Relief Commission, which fed children in occupied Poland until 1941 and the U. S. entry into the war. In 1946, President Harry S. Truman asked Hoover to head the Famine Emergency Commission to address postwar famine in Europe. In 1947, Hoover asked Congress to appoint a commission to examine the reorganization of the executive branch and address inefficiency in the federal government. The resulting Hoover Commission offered nearly 300 recommendations for change, more than two-thirds of which were accepted and which enhanced the managerial powers of the president. Hoover died on October 20, 1964.

Further reading: David Burner, Herbert Hoover: A Public Life (New York: Knopf, 1979); Joan Hoff Wilson, Herbert Hoover: Forgotten Progressive (Boston: Little, Brown, 1975).

—Shannon L. Parsley

World History

World History