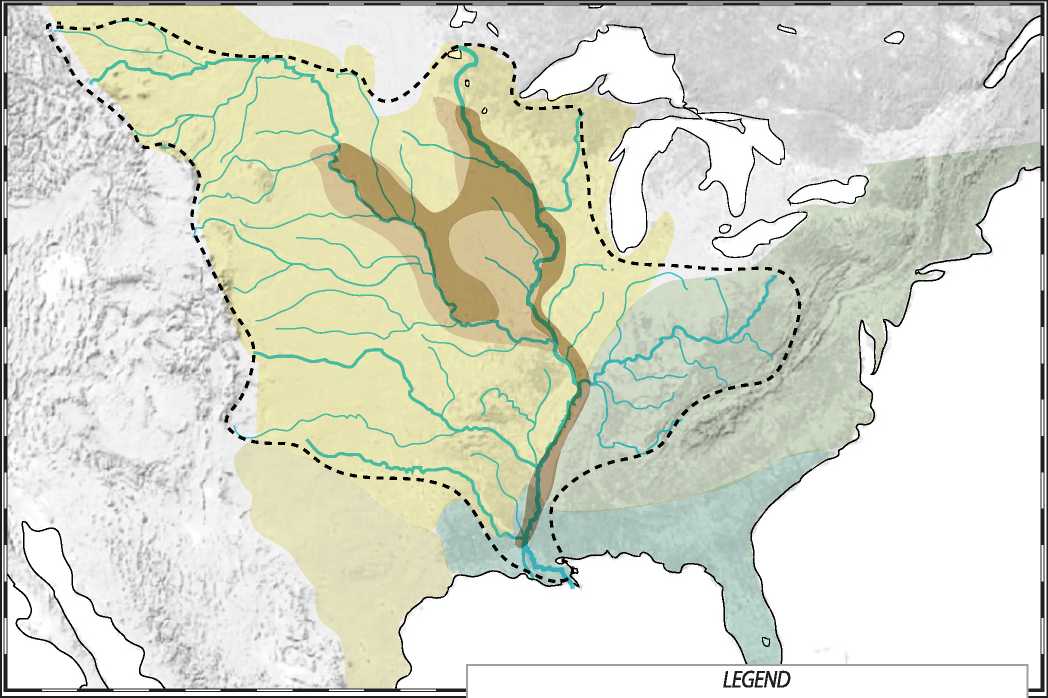

Just as the corn that was brought to the southwest had to be made compatible to native plants and arid conditions, the corn that was brought up the Mississippi had to be integrated into forest and riverine conditions. It followed the web of habitations along the shores of the waterways, first northward and then eastward toward the Atlantic where it arrived at a crucial moment just when the Hopewell Tradition was in decline and mound building at an end. With the arrival of corn planting, however, the mound-building tradition was revived as well as the ceremony-oriented way of life that had once operated in the region. The area had a huge advantage. Corn grows best in land with deep layers of mineral-rich soils known as loess. In the United States this is found exclusively along the Mississippi River and in an area that stretches

Figure 16.19: Mississippi River drainage and major urban sites, 1000-1600 ce. Source: Florence Guiraud

PRAIRIE

WOODLAND

SWAMP FOREST DESERT

LOESS

RIVERS

From Ohio to western Wisconsin and into Nebraska, which is why today this area is known as the Corn Belt. In ancient times, before modern machinery, the use of the loess in this area was limited, however, since the prairie with its deep roots and tough grass was not suitable to farming (Figure 16.19).

Because many of the rivers had high blufis, making weir-dam canals was impossible. As a result, unlike in Mexico, Peru, and in parts of the Southwest, irrigation was never practiced here. The choice was to either clear the forest in search for well-watered, low-lying areas or to farm the river flood plains. It would be wrong, however, to think that these people were less advanced than the southern cultures with their irrigation techniques. The loess and plentiful rain made irrigation less necessary. Corn and its associated agricultural practices did, however, radically transform the landscape, perhaps even more so since neither monsoons nor rapid jungle growth compensated for forest removal. In the cleared land, small mounds by the thousands were created with the corn planted on the tops. Corn was occasionally planted on the top of long parallel ridges, some still visible today as far north as Michigan. The mounds and ridges protected the plants from an early frost or late snow and also provided more soil on which to plant.15 Another way to grow corn was to exploit, where possible, the bottom lands of rivers that so far had only been used for Ashing, hunting, and transportation. The rich soil there was replenished every year with the flood. But to move into these bottom lands was a bold step that required preplanning and a great deal of risk. It also required powerful elites that could organize and control a substantial workforce, while imposing and naturalizing the new corn-centric mythology on the people.

World History

World History