The west Trans-Baikal region of Siberia, wherein is found Kamenka (Bath House Stove) and other Paleolithic open sites (Figs. 3.24-3.26), has a substantial history of scientific investigation despite its distance fTom Moscow and St. Petersburg. The archival research by Ludmila V. Lbova and E. A. Khamzima (1999) found that the first Trans-Baikal scientific expeditions began in 1724, led by D. G. Messershmidt, who noted numerous stone graves that looked like a “fossil army” (Fig. 3.27). The members of the second Kamchatka expedition (G. Miller, I. Gmelin, others) undertook the first excavation in 1743 of burials in the area of today’s Yeravninski reservoir. More than two centuries had to pass before the deeply buried Kamenka site would be discovered.

The Kamenka site is located near a settlement named Novaya Bryan, about 2 km west of the Bryanka River that flows through a sandy steppe valley flanked by hills darkened by small stands of conifer trees (51°460 N, 108°20' E). It consists of an accumulation of cultural and faunal remains of a repeatedly occupied large Upper Paleolithic open camping area. Kamenka is named after a low mountain on whose southeastern lower slope it appears, at about 600 m elevation. Artifacts and faunal remains were first discovered at Kamenka in 1989 by local school children and their history teacher due to exposure caused by workers removing sand and gravel from a large barrow pit for use in construction elsewhere (Abdulina and Tashak 1990). The Kamenka locality was saved from further destruction by the actions of Lbova, who had Kamenka legally designated as a cultural monument. She then directed the scientific sampling of the site fTom 1989 to 1995 for the Buryat Institute of Social Sciences of the Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences (now the Institute of Mongolian, Buddhist and Tibetan Studies) (Lbova 1991a, 1991b, 1996,2000; Lbova and Volkov 1993; Lbova and Germonpre 1994; Lbova and Shteinokova 1996; Germonpre and Lbova 1996; Lbova etal. 2003). Judging from published site maps (Lbova 2000:162-165; and elsewhere), approximately 300 m2 was excavated. Artifacts included knives, linescrapers, perforators, points, and burins. Wear analysis shows most were used for butchering animals, treating hides, and producing bone tools (Lbova 2002, Lbova et al. 2003). Hearths and a possible tent ring were also found deeply buried under sandy soil with various amounts and units of fine gravel, clays, and some calcification (Lbova 1991a, 1991b, 2000, Germonpre and Lbova 1996). Paleopedological features suggest that the main human occupation occurred during the warmer Karginsk interstadial, which was followed by the cold Sartan stadial.

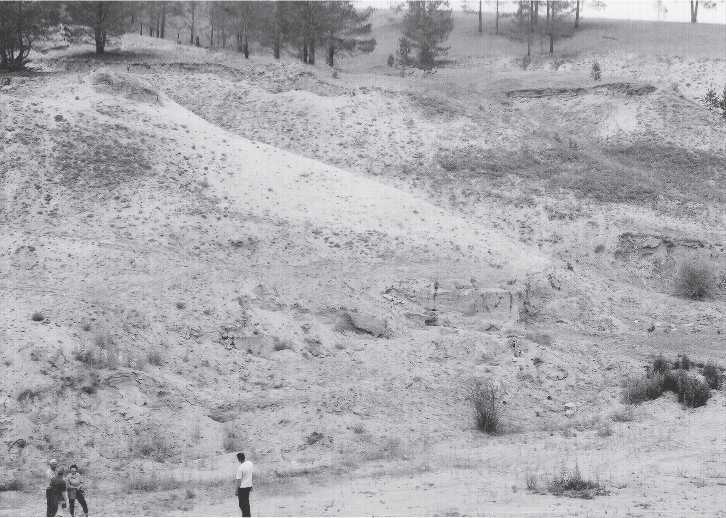

Fig. 3.24 The Kamenka site. Excavated by Ludmila Lbova, the Upper Paleolithic cultural horizons are near the level where the people are standing (CGT neg. Kamenka 7-8-03:16).

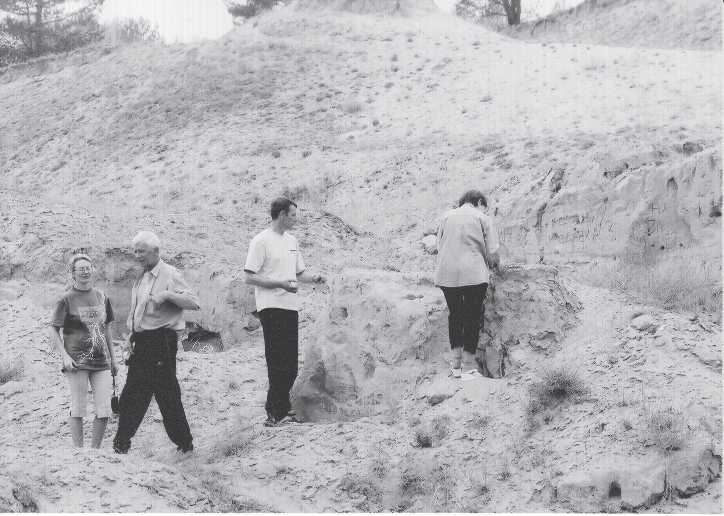

Fig. 3.25 The Kamenka site. Visitors are examining the Upper Paleolithic cultural horizon on which they are standing. Left to right: Ludmila Lbova, Nicolai Ovodov, driver, Olga Pavlova (CGT neg. Kamenka 7-8-03:11).

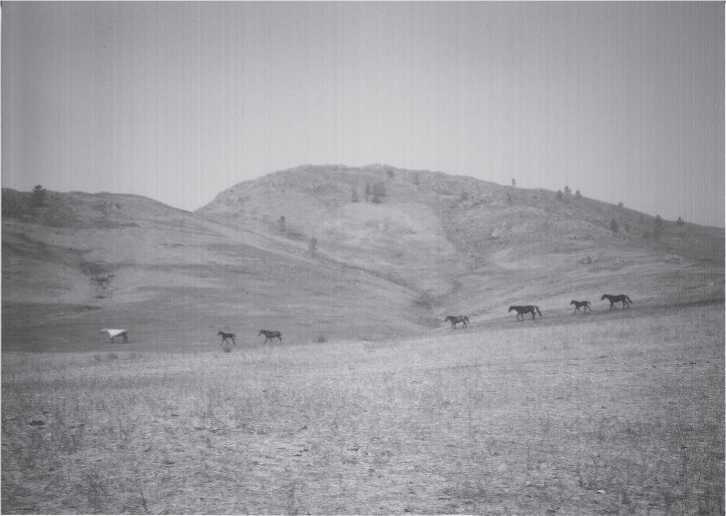

Fig. 3.26 Odyssey. A small herd of horses. On the trip to Kamenka and Varvarina Gora, Ludmila Lbova also showed the authors her ongoing excavations at Khotyk. This locality, like much of the region around the Trans-Baikal population center of Ulan-Ude, is steppe. One evening a herd of horses trotted by our tents, provoking a mental image of what Upper Paleolithic hunters might have similarly seen in this locality (CGT neg. Khotyk 7-8-03:7).

Vasili’ev et al. (2002) have compiled many of the published carbon-14 dates for Paleolithic Siberia, including ten obtained from Kamenka (they did not include for technical reasons a date of 28 000 BP, included in the 11 dates published by Lbova [2002:63]). Bone and charcoal carbon-14 dates range from 24 625 BP to 40 500 BP, with an average of 30 200 BP. Oxford University radiocarbon dating laboratory dates released in June 2003 are 41 350 BP and 39 290 BP (Lbova, personal communication, June 30, 2003). Thus, Complex A (C) (middle Karginsk time) ranges fTom 26 760 to 41 350 BP, and Complex B from 24 625 to 28 000 BP (late Karginsk time). This range of dates conforms with established dates for the Karginsk interstadial. Site components A and C have typological stone tool similarities in their blade forms, whereas Component B is more varied, although dates for the three components are much the same. On the whole, the existence of this hunting camp (dates, bone-processing technology, and stone tool types) is viewed as transitional from Mousterian to the Upper Paleolithic. We restricted our taphonomic study to bones recovered only from Component A, generally the deepest of the three, and with many times more specimens.

As stated in the methods section of Chapter 1, we limited our formal observations to pieces whose maximum diameter was greater than 2.5 cm, and whose surfaces had little or no root damage. Rarely, we scored pieces with heavy root damage when it was limited

Fig. 3.27 Odyssey. Forest fire smoke. The sun was almost completely blotted out by the acrid and eye-watering smoke fTom lightning-ignited forest fires far to the north of Ulan-Ude.

Unreachable, these huge fires burn for months. Similar wildfire conditions likely existed in Pleistocene Siberia and were likely to have been an aid to hunters waiting in ambush for game fleeing the fires. This scene also shows a large grave near Khotyk believed to have been excavated by Professor Messerschmidt in 1742 of the Second Academic Expedition to Kamchatka (Lbova and Khamzina 1999). He allegedly found only a few horse bones as the grave had been looted at some earlier time. Left to right: Olga Pavlova, Nicolai Ovodov, and Ludmila Lbova (CGT neg. Khotyk 7-8-03:14).

To one surface or small area. We also did not count most whole pieces that lacked perimortem damage of any sort. These included almost all loose teeth and foot bones. Unlike other sites, especially Ust-Kan, Kamenka contained many teeth and cranial parts. The Kamenka assemblage, like all other sites, was curated in many plastic bags and whatever sorts of cardboard boxes Lbova and her student workers had available. Our working area was limited to one small table. Hence, our study proceeded by opening a bone bag, making and recording observations, doing macrophotography, returning the pieces to the bag, and then moving on to another bag. We were unable to attempt any inter-bag conjoining. Moreover, each bag might contain not only various species, various skeletal elements, but also differing provenience designations, such as I1, K4, I10, K9, no number, and so forth. The basis for bag contents was partly year of excavation, but also unknown reasons.

The faunal collection of Kamenka has been analyzed by M. Germonpre and published (Germonpre and Lbova 1996): mammoth (Mammonteus primigenius), one piece; horse (Equus cf. Caballus), 191 pieces; Asiatic wild ass, onager (Equus

Hemionus), one; rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), ten; camel (Camelus sp.), three; bighorn deer (Megaloceros giganteus), two; Mongolian gazelle, zeren (Procapra guturoza), 229; wild sheep (Ovis ammon), seven; bison (Bison priscus), 17; cave lion (Panthera spelaea), one; horned ungulates (Bovidae gen. sp.), seven; indeterminable mammals, 1532.

World History

World History