From the hindsight provided by nearly three hundred years of history, the Pueblo Indian Revolution of 1680 is to be understood most profoundly as a great act of restoration by the ancestors of today’s Pueblo Indian people.

—Ortiz (2005: 2)

On 5 August 1980, thirty-four Hopi and six Taos runners gathered in the plaza at Tuahtah (Taos Pueblo) in northern New Mexico (Sockyma and Sockyma 1980). They said their morning prayers with sacred corn meal, washed their faces in the nearby stream, and then received instructions from the governor of Tuahtah. They were told of the solemnity and importance of their mission and then one Hopi and one Taos runner were given a leather pouch. This pouch contained a message written on buckskin inviting all the Pueblo people to gather on 9 August for a historic meeting at Kewa (Santo Domingo Pueblo). It also contained a cord with two knots to commemorate the day when Catua and Omtua, the two runners from Tetsugeh (Tesuque Pueblo), were captured and killed by the Spaniards. These two runners then led the group out of the plaza on their long journey to Second Mesa at Hopi. So began the run to re-enact the dedication of their ancestors and celebrate the tricentennial of the famous Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

The Pueblo Revolt or, the first American Revolution as Joe Sando (1998: 3) calls it, is an American story of freedom and resistance to tyranny. After eighty-two years of living under Spanish rule, Pueblo Indian people and their Navajo and Apache allies rose up in a

Coordinated attack to throw off the yoke of Spanish authority. First at Tetsugeh and then at many other villages, Pueblo warriors attacked their mission priests and set their mission churches on fire. For nine days, they besieged the Spanish capital of Santa Fe, finally forcing Governor Antonio de Otermin to retreat in disgrace to El Paso del Norte (now Ciudad Juarez, Mexico). A total of 401 Spanish settlers and 21 Franciscan priests lost their lives in the uprising. The number of Pueblo people killed, however, is not recorded. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 was thus the earliest and most successful native insurrection along the northern Spanish frontier. And yet, the revolt is almost never mentioned in US history textbooks (but see Weber 1999). This fact speaks to the ongoing marginalization of Native American histories and their segregation within contact period scholarship.

The Pueblo Revolt period has not been a focus of sustained archaeological research. Although southwestern archaeology was founded on the study of mission villages, particularly Pecos (Bandelier 1881; Kidder 1916, 1924, 1958), Hawikku (Hodge 1918, 1937), and Awat’ovi (Montgomery et al. 1949) (some of which were burned during the revolt), the focus quickly shifted to the study of the ‘prehistoric’ past, in particular the archaeology of sites such as Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. The colonial encounter came to mark a convenient break between modern Pueblo life, the domain of ethnographers, and the deep past, the purview of archaeologists. The segmentation of time created an implicit barrier to holistic research linking Pueblo pasts to Pueblo presence. Only recently, with the emergence of resistance and identity as scholarly topics, has the field returned to the colonial encounter as a research area. This is now expressed by the renewed interest in mission pueblos (Adler and Dick 1999; Ivey and Thomas 2005; Lycett 2002), mesatop ‘refugee’ villages (Ferguson 1996a, 2002; Liebmann 2006; Liebmann et al. 2005; Preucel 2000a, 2000b, 2006; Preucel et al. 2002; Wilcox 2009), pueblitos (Towner 1996, 2003; Towner and Johnson 1998), and the Spanish capital of Santa Fe (Shapiro 2008; Snow 1974).

In our chapter, we wish to contribute to the study of the Pueblo Revolt period by introducing a place-based approach emphasizing the ontological interdependence of time, space, and history. Our starting point is the idea that places embody history both physically and spiritually and that historical memories are given life when people re-encounter these places. For example, the 1980 re-enactment of Catua and Omtua’s run by selected Pueblo youth not only brought forth the memory of the revolt but it also publicly reconfirmed the same social values that made the Pueblo Revolt successful. Similarly, our choice to do archaeology at the post-Revolt mesa villages occupied by Pueblo ancestors not only provides us with an opportunity to engage with Pueblo history, but it also requires us to consider the implications of our research for contemporary Pueblo communities. At the same time, it causes us to reflect upon our different subjectivities. One of us (Aguilar) is a member of Powhoge owingeh (San Ildefonso Pueblo), conducting research on a village occupied by his ancestors, while the other (Preucel) is a Philadelphian collaborating with Cochiti Pueblo in the study of their ancestral village. Both of us share a commitment to providing opportunities for Pueblo youth to visit these ancestral places and learn about their ongoing significance.

This place-based perspective is essential for the further development of indigenous archaeology (Smith and Wobst 2005; Watkins 2000; see Gould, Mrozowski, this volume). There are several reasons for this. First, a place-based approach embraces the strong link that the Pueblo and other indigenous peoples maintain with their past. For Pueblo people, there is no disconnect between place and time—the contemporary world and that of their ancestors are embedded in the same place—and it is this reality that generates their continuing attachment to these places. Second, a place-based perspective furthers the aims of an indigenous archaeology by rejecting the false dichotomy between history and prehistory and the implicit assumption that places of history are linked to entangled European/indigenous encounters, while places linked exclusively to an indigenous past are part of prehistory (see Pawlowicz and LaViolette, this volume). This approach also resonates with perspectives developed in African archaeology, especially how the presencing of the past occurs in ritual settings where deep time histories and more recent histories figure prominently in the lives of people today (Lane, Schmidt, and Walz, this volume).

13.1 PUEBLO PLACEMAKING

Placemaking is sometimes defined as the social practices of constructing place (Preucel and Matero 2008: 84). From this point of view, it is as characteristic of indigenous cultures as it is of modern Western capitalist society. Because the making of place is an inherently political process, certain places may be incorporated into sanctioned views of the social imaginary. Places of resistance, such as battlefields, may be sanitized and depoliticized as they are incorporated into specific narratives emphasizing the continuity of past and present. Alternatively, they may be recuperated and used to deny continuity as a means of challenging the dominant social order. What is and is not considered to be a place is thus part of an ongoing dialogue involving contestation and negotiation. The refashioning of space into place is a technology of reordering reality, and its success depends on the degree to which this refashioning is concealed in the details of material culture and site plan and the degree to which it generates habitual action.

This perspective, as useful as it is, can be criticized for being somewhat one-sided. It considers how people make places, but unfortunately pays less attention to how places make people. One of the central premises of contemporary indigenous studies is that place has its own agency and life-force (Cajete 2000). Places and people exist within a moral landscape structured by reciprocal relationships of obligation such that places give people wisdom and people give places respect. It is the balance of obligations that simultaneously constructs personal identity and ensures cultural survival. As Keith Basso (1996) notes, places offer a remarkable capacity for triggering acts of self-reflection, inspiring thoughts and memories. He suggests that places ‘animate the ideas and feelings of persons who attend to them’, just as ‘these same ideas and feelings animate the places on which attention has been bestowed’ (Basso 1996: 107). Many indigenous peoples recognize a set of responsibilities associated with being-in-the-world that requires honouring all living things, from plants and animals to mountains and spirits. Because things are not always in balance, there are forces of chaos at work that can make some places dangerous; places require respect and spiritual preparation.

For Pueblo people, places are given meaning through the movements of sentient beings (people, animals, and deities) and their encounters with one another. For example, when the Hopi emerged from the underworld and entered the Fourth Way of Life, they entered into a spiritual covenant with the deity Maasaw to journey until they reached their destiny at Tuuwanasavi (‘the centre place’) (Kuwanwisiwma and Ferguson 2004: 26). They were instructed to leave ang kuktota (‘footprints’) to demonstrate that they met their spiritual obligations. Today, Hopi point to the ruins of former villages and the potteries, stone tools, petroglyphs, and other artefacts left behind as offerings as the footprints of their ancestors. These footprints are thus tangible proof of ancestral clan migrations and land stewardship (Kuwanwisiwma and Ferguson 2004: 26). But they are also intangible evidence since they embody place-names that are incorporated into prayers and songs as part of specific ceremonies.

Locating past events in absolute time in the manner that archaeologists have traditionally favoured is not a priority with Pueblo people. Rather, what is important is not so much when things occurred, but where they occurred and what these places can reveal about Pueblo society and cultural values that is useful in the present. This place-based perspective collapses the standard distinction between prehistory and history and allows people an ongoing dialogue with their ancestors to guide appropriate behaviours. That dialogue is essential for building closer ties within the community and unveils how history is produced and memorialized (see Lane, Schmidt, Walz, this volume). Places are nodes in a sacred geography that links together mountains, mesas, rivers, and villages. Alfonso Ortiz (1969) and Rina Swentzell (1993) have eloquently described how the Tewa world is organized according to blessings and energy flows radiating outward from the village plaza to the mountaintops and back again to the village. This general principle, if not the specific details, is widespread among all the Pueblos.

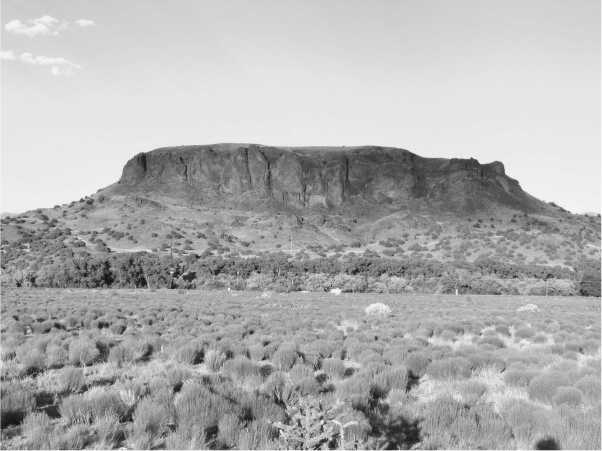

The mesas located in the cardinal directions near villages are especially venerated. For example, Tunyopin (‘spotted mountain’) or Black Mesa is located due north of Powhoge (Fig. 13.1). It figures prominently in many San Ildefonso stories. It contains a cave where a giant lives with his wife and daughter (Harrington 1916: 295). This giant was known to eat little children until he was killed by the War Gods. Parents today still warn their children to be careful or they will be taken away by the giant. Traditional stories mention that the mountain once emitted smoke and

Fig. 13.1. Tunyo, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico (photo: Joseph Aguilar)

Fire. The mesa is also the location of one of the most famous of the Tewa Revolt period villages. This village is called Tunyo kwaje teqwakeji (‘old houses on the top of Tunyo’) (Harrington 1916: 297). Because its walls were built of cobblestones from the Rio Grande gravels and have long ago collapsed, there are no room block alignments visible. The importance of place is perhaps best indicated by the fact that dances were traditionally performed on top of the mesa (Harrington 1916: 295).

Similarly, the Pajarito Plateau is a sacred place for the people of Powhoge. It is the location of many ancestral villages, such as Potsuwi (‘village at the gap where the water sinks’), Sankawi (‘village at the gap of the prickly pear cactus’), Navawi (‘village at the gap of the gamepit’) and Nake’muu (‘village on the edge’). Nake’muu is the revered place that was rebuilt and reoccupied during the Reconquest period. The name refers to the location of the village at the confluence of Water Canyon and Canon de Valle, on the narrow point at the end of a mesa. The physiographic setting of Nake’muu is quite dramatic, and a visit to the site leaves no doubt as to why the site was used as a place of refuge. Perhaps due to its clandestine location, where very few if any Spanish soldiers had ever ventured, miles away from the stronghold of Tunyo, there is no mention of Nake'muu in the historical literature. However, the site is well known to archaeologists ever since Edgar Lee Hewett (1906) visited the site and produced the first sketch maps of the village, calling it the ‘the best preserved ruin in this region’. Although no archaeological excavations have taken place, the site has been extensively remapped and photographed by Los Alamos National Laboratory in consultation with Powhoge as a part of a long-term monitoring project (Vierra 2003).

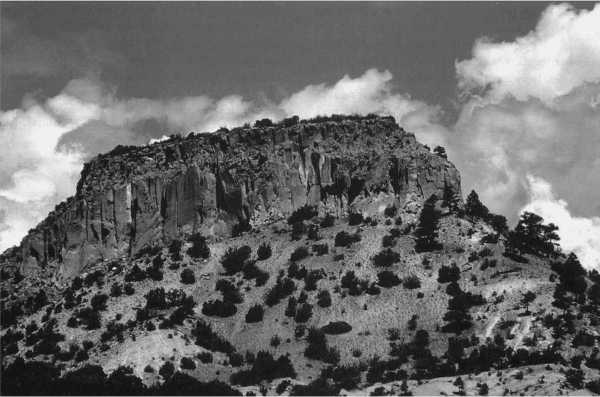

Hahn Mesa (people’s mesa), or Cochiti Mesa, located 7 miles northwest of Cochiti, is a sacred place for Cochiti people (Fig. 13.2). It is the location of one of their ancestral villages occupied after the Revolt of 1680. It is known as Hanat K’otyiti (‘Cochiti above’). Other Cochiti names include K’otyiti shoma (‘old Cochiti’), K’otyiti kamatse shoma (‘old Cochiti settlement’), and K’otyiti haarctitc (‘Cochiti houses’) (Harrington 1916: 432). The main village is a large double plaza pueblo. There are at least 137 ground-floor rooms distributed in six room blocks and a kiva in each plaza. All of the rooms are constructed of shaped tuff blocks set into an adobe mortar. The masonry work is generally quite good and, in some places, the walls stand 3 m high. Viga and latilla holes are present in upper levels of several walls and these provide direct evidence for roofs and possibly second-storey rooms. Many rooms have well-preserved wall features such as doorways, vents, niches, and pole sockets. Quite a few walls have large expanses of intact plaster, and some of this is discoloured from burning. Artefacts are concentrated in

Fig. 13.2. Cochiti Mesa, New Mexico (photo: Robert Preucel)

The shallow midden areas to the north, east, and south of the village. Approximately nine single room structures and several indeterminate features are located immediately outside the room blocks. Tree ring dates indicate an occupation date as early as 1684 (Preucel et al. 2002).

A secondary village, or rancheria, is situated approximately 150 m southeast of the plaza pueblo. It consists of an informal grouping of approximately twenty-seven non-contiguous structures, ranging from one to two rooms in size. These structures are all highly eroded and in some cases the wall alignments are completely obscured. The building materials are tuff, and there is a markedly higher proportion of irregular to shaped stones than at the plaza pueblo. The spatial arrangement of the structures is rather loosely organized and extends in a linear fashion approximately 160 m down the mesa. Some structures possess a general northwest-southeast orientation, while others have a northeast-southwest alignment. There is no evidence for ritual architecture. The pottery indicates that the rancheria dates to the Reconquest period and may be contemporary with the plaza pueblo or possibly built during the 1696 Revolt (Preucel 2000a).

13.2 RESTORING THE TEWA WORLD

The San Ildefonso Indians preserve traditions of this siege. Brave Indians used to descend every night through the gap and get water

From the river for the besieged people to drink. The Spaniards were afraid to come near enough to be within range of rocks and arrows. The stone wall and the ruined houses probably date from the siege of Vargas, but still older remains of walls and houses may be discoverable on the mesa.

—Harrington (1916: 294-5)

Although only occupied for nine months, Tunyo was a major centre of resistance during the Reconquest of New Mexico. Of all the mesa villages established in the northern Rio Grande, it was the largest, possibly housing as many as 2,000 people. At different times, it served as the home for people from seven Tewa villages: Powhoge, Kha’po (Santa Clara), Nanbe, P’osuwaege (Pojoaque), Tetsugeh, Kuyemuge (Cuyamun-gue), and Sakona (Jacona), and two Tano villages: Yam p’hamba (San Cristobal) and Ipere (San Lazaro). Vargas attacked the mesa three times but never succeeded in capturing the village; the final encounter was not a military defeat but a negotiated surrender. Vargas first mentions that the Tewa had taken refuge on Tunyo on 9 January 1694 (Kessell etal. 1998: 41), shortly after and in response to a devastating battle and the execution of seventy pueblo defenders and leaders in Santa Fe just days earlier. A day later, Vargas describes his conversation with Domingo, a war captain from Tetsugeh whom he met halfway up the mesa in an effort to secure the Tewa surrender. Vargas states ‘he spoke, saying that he was not coming down because he was not well. He and the others repeated that they were not coming down. They were afraid because of what happened to the Tanos (in Santa Fe)’ (Kessell et al. 1998: 44).

Vargas, however, does not mention the people from Powhoge who took refuge on the Pajarito Plateau at their ancestral village of Nake’muu. Oral tradition records the journey of women and children from Powhoge to Navawi and then up the canyons to Nake’muu (Vierra 2003: 12). Nake'muu is a small plaza pueblo originally constructed during the Late Coalition period (1275-1325 ad) and containing at least fifty-five ground-floor rooms distributed in four room blocks. A close inspection of the wall construction sequence indicates that two separate linear room blocks were initially built. Sometime later a series of lateral northern and southern room blocks were added, enclosing a central plaza. The outside doorways were subsequently sealed, and the focus of the pueblo became the central plaza area (Vierra 2003: 3). The walls are constructed of shaped tuff blocks quarried from the local bedrock and held together by adobe mortar. One possible explanation for the excellent condition of the walls is that the roofs may have been repaired during the Reconquest. Traditional knowledge about this sacred place has been passed down at

Powhoge through oral traditions and annual visits to the village by tribal members. These oral traditions stand as strong testimony to the links between the recent and deeper pasts and their role in shaping notions of the sacred.

Despite its historical significance, virtually no systematic archaeological work has been conducted at Tunyo, and it remains relatively poorly understood. One reason for this neglect is that the mesa lies on Powhoge lands, allowing the Pueblo to exert strict control over who is allowed access. Just as Pueblo people defended the mesa in 1694, so, too, do they defend it today from perceived modern threats, such as unwelcome visitors. Another reason may be the popular belief that archaeology can contribute little to an understanding of the historic period (a view clearly contradicted by the success of historical archaeology). Surprisingly, Adolph Bandelier was sceptical of the archaeological value of Powhoge and Tunyo, stating, ‘the pueblo of San Ildefonso, or Po-juo-ge, offers nothing of archaeological interest. Neither does the black mesa called Tu-yo, two miles from the village, deserve attention except from an historic standpoint’ (Bandelier 1892: 82).

In 2009, Joseph Aguilar began preliminary archaeological fieldwork at Tunyo. The overarching goal of his project is to assess the archaeology of Tunyo as well as to evaluate the ethnographic and historical data within the context of Powhoge cultural preservation initiatives. Aguilar’s research is beginning to shed new light on our understanding of the historical events that took place there, especially the role the mesa played as a place of refuge for Pueblo people during the Reconquest. Needless to say, an understanding of the archaeological history at Tunyo by Pueblo people is not necessary for their appreciation of the sanctity and significance of the mesa. However, such information can only enrich Pueblo people’s perspectives, as these new ways of knowing and understanding the past can supplement their already strong convictions about place. The same is true of archaeologists seeking to make better use of Pueblo oral traditions in their own research, thereby embracing an indigenous perspective concerning the production and maintenance of history (see Schmidt, this volume).

The scope of Aguilar’s work thus far has focused on documenting the defensive features located along the perimeter of the mesa that were used as part of a defensive strategy against the Spaniards. These features take on two main forms: linear rock alignments and caches, or piles of river-rolled quartz cobbles. The linear rock alignments consist of stacked courses of shaped and unshaped basalt rock. These alignments range from one to seven courses high, and range from less than 1 m to more than 1.5 m in height. The lengths of these alignments range from less than 1 m up to 10 m, although it appears that some segments have eroded away and may have been longer. Furthermore, some alignments may have been connected to others, making some even longer still. The alignments are straight or curvilinear, while in some instances alignments are to the topography of the mesa edge. The rock caches consist of conspicuous piles of river-rolled quartz cobbles, but at least two of these caches are composed of basalt slabs. All of these caches, like the wall segments, occur along the perimeter of the mesa, and in some instances are located directly behind and/or adjacent to the rock alignments. The numbers of individual cobbles within each cache vary. Some contain no more than thirty cobbles, while others contain hundreds. Some caches are small (less than 1 m in diameter) dense aggregations of cobbles, and others are distributed over a relatively larger area (a few metres in diameter). The diameter of individual cobbles within these caches also varies from approximately 3 cm to 10 cm. Most of these cobbles are roughly the size of an average man’s fist.

The geology of the mesa is quite distinctive. The mesa itself is a large basaltic extrusion, with a highly eroded centre. Geologists from Los Alamos National Laboratory and Glorieta Geoscience, Inc. have identified a stratigraphic layer of river gravels, approximately 10 m thick that sits atop the mesa (Steve Reneau and Paul Drakos, personal communication, 2008). The gravel cap suggests that an ancient riverbed once existed at the present summit of the mesa but has since eroded away, only to be remarkably preserved atop the hard basalt. Given the natural abundance of basalt and river cobbles on the mesa, and that the archaeological features are composed of these materials in an unmodified form (e. g., rocks composing the alignments are not shaped), the distinction between what is natural and what is archaeological is somewhat challenging. However, closer scrutiny of the spatial distribution of these features and their physical composition clearly indicates that they are not naturally occurring phenomena but are better interpreted as part of a defensive strategy employed by Pueblo people during the Spanish sieges.

Preliminary surveys have identified seventy-one rock caches and seventeen rock alignments, including segments and fragments. The spatial distribution of these features shows that both types, rock caches and rock alignments, occur only on the perimeter of the mesa and not on all parts of the perimeter. The topography of the mesa may lend some explanation to this irregular distribution along the perimeter. Where the topography of the mesa is at its absolute steepest on the western side of the mesa, where cliff walls are at least 60 m (200 ft) high, neither feature types are present. There are instances where rock caches do occur at relatively steep portions of the mesa; however, these are points where known trails traverse the mesa top. The majority of both feature types are spatially distributed near or along areas where the topography of the mesa is significantly less steep, or relatively easily accessible, and/or where known trails traversing the mesa top exist.

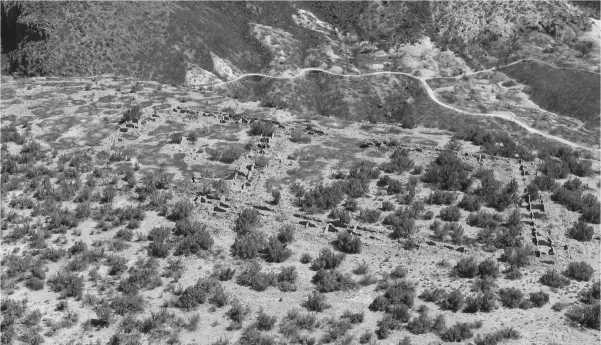

It is impossible to give absolute dates to the construction of these features. But inferential evidence strongly suggests that they were used as part of a defensive strategy. First, an examination of the topography of the mesa, in conjunction with the spatial distribution of these features, shows that these features were distributed with defence of the mesa in mind. These features are concentrated at places where there are known trails, so we can infer that they were strategically positioned at these points for the purpose of defending these routes up the mesa. It is precisely at these points that a potential enemy wishing to attack the mesa would make their attempt. Indeed, Vargas reported on the Pueblo use of fortifications and the hurling of stones against Spanish forces during the siege. For example on 11 March 1694, during the first battle, Vargas notes that a squadron of twenty men attacked the main path up the mesa, which was said to be heavily fortified (Kessell et al. 1989: 160). Furthermore, Vargas observed the Pueblo defenders atop the mesa countering the Spanish offensive by throwing large slabs or rock and hurling stones from above. At other points, where the topography of the mesa is more pronounced, the mesa was naturally defensible and did not require any artificial defence. Where known trails traverse the steep cliffs through natural gaps, there are a few rock caches, presumably defending these passageways. Harrington (1916: 298) identifies one of these gaps as Tsampije kutsipo’e or ‘little trail of the notch in the rock at the west side’. He describes this gap through which ‘brave young Tewa went down to the river to get water at night when the San Ildefonso people were besieged by Vargas on top of the mesa in 1694’ (Harrington 1916: 298). This trail is still well known to the people of San Ildefonso today, and two rock caches have been identified at this point (Fig. 13.3).

The layout and organization of the mesa village is not yet clear. There are no ethnohistorical descriptions of the village because Vargas never climbed the mesa. The fact that it was built to house people from multiple Tewa villages suggests that it would have involved planning by the Powhoge cacique and a number of other Pueblo leaders. During the siege, the village had to accommodate the people from multiple villages. Vargas mentions that he observed 1,000 people defending the mesa, although, as Hendricks (2002: 185) has noted, there is some debate about this. Although we do not yet know the exact architectural form of the village, the extent of the village area has been recorded and its boundaries defined. Preliminary research suggests the village area

Fig. 13.3. Rock caches or ammunition piles overlooking the main trail to the top of Tunyo (photo: Joseph Aguilar)

Encompasses approximately 10,000 m2. This is certainly not all residential living space, and includes what appear to be several separate room blocks, distributed in an irregular pattern, and a possible plaza area. It seems likely that the topography of the mesa and the defensive features helped secure this defensive position rather than the form of the village. A similar conclusion has been drawn at the refugee community of Dowa Yalanne near Zuni, where it has been shown that the mesa itself, and not the architecture of the village, provided defensibility (Ferguson 1996a: 119).

By the time of the last battle from 4 to 9 September 1694, Nanbe had joined the community. At this time, there may have been as many as 2,000 people on the mesa, several hundred of whom could have been warriors, although the actual number is difficult to estimate (Hendricks 2002: 193). After nearly nine months of isolated living on Tunyo, and after three major and bloody battles, the siege finally came to an end on 9 September 1694. The Tewa of Tunyo negotiated a peaceful settlement and thus avoided the fate of the Keres at Hanat Kotyiti, where 342 noncombatants and 13 warriors were captured and their village destroyed, and the defeat of the Jemez at Astialakwa, where 84 Jemez defenders were killed, some of whom jumped to their deaths or were burned in their homes. The Tewa were not defeated in battle and came down voluntarily from their mesa stronghold to begin the long process of repairing their villages and mission churches.

Today, Tunyo and Nakemuu are held in the collective memory of the different Tewa villages involved in the siege. The events that occurred are not recalled as specific dates in history, but rather as part of an unfolding past that is inseparable from the present and that require prayer and a show of reverence when the mesas and their villages are visited. Tunyo is not just a site of refuge occupied during the Reconquest period, but a place where supernatural deities and Pueblo ancestors are alive. The significance of Tunyo and Nake’muu, therefore, is anchored in those places themselves, and in their associations with deities and ancestors which are continually memorialized through pilgrimage and prayer. This holistic understanding is an example of the value of an indigenous, place-based archaeology that embraces the strong connections between place and history and rejects the notion of absolute time embedded in the concept of prehistory.

13.3 RESTORING THE KERES WORLD

All these pueblos had already come down off their mesas and have been given lands by the Spaniards. Only the people of Cochiti were still on their mesa. There was only one trail up to the pueblo, and at the top the people had piled boulders. When any enemy came up the trail, they rolled down a boulder and killed him.

—Santiago Quintana, Cochiti Pueblo (Benedict 1931: 185)

In 1995, Robert Preucel established the Kotyiti Research Project with Pueblo of Cochiti as a multi-year collaborative research project focusing on the archaeology of their post-Revolt period village of Hanat Koytiti. The central goal of the project is to identify the social processes surrounding the founding and occupation of Hanat Koytiti and to understand the meaning and significance of the village and mesa to the Cochiti people today. The project has four main components: the production of a map of the two villages constituting the Hanat Kotyiti community; an archaeological survey of mesatop and adjacent areas; an oral history project; and an internship programme for Cochiti youth. Hanat Kotyiti is well known in the archaeological literature. Adolph Bandelier first mapped the village for the Archaeological Institute of America in 1880; Nels Nelson then mapped and excavated the village for the American Museum of Natural History in 1912; and, most recently, Julia Dougherty surveyed and mapped the village and mesa for the US Forest Service in 1979.

Our research reveals that Cochiti Mesa was an early and persistent stronghold of resistance throughout the Reconquest period. When Juan Dominguez de Mendoza arrived at Sandia Pueblo on 10 December 1681, as an advance guard of Antonio de Otermin’s entrada, he learned that the people of Sandia, Puaray, and Alameda had all taken refuge with Alonso Catiti in the mountains of Cochiti or Cieneguilla (Hackett and Shelby 1942: 226). Catiti was known as the ‘supreme leader’ of the Keres people and he, along with Po’pay and other leaders, played an important role in planning the Revolt of 1680 (Hackett and Shelby 1942: 241-2). In several interviews, Mendoza discovered the people of Cochiti, San Felipe, and Santo Domingo had all fled to Cochiti Mesa (the sierra of Ciene-guilla) upon news of the Spanish attack on Isleta and that they were meeting in a war council (Hackett and Shelby 1942: 236). There is, however, no evidence for a village on the mesa at this time. Twelve years later, Don Diego de Vargas, the new governor of New Mexico, climbed the mesa and found a thriving pueblo. He entered the village and learned that the rebels were from the three villages of Cochiti, San Marcos, and San Felipe (Kessell and Hendricks 1992: 515-16). He pleaded with the people to come down and reoccupy their mission homes; however, only the San Felipe people complied. Because the Cochiti warriors were raiding the livestock of Santa Fe, he returned to the village on 17 April 1694 and made an early morning attack (Kessell etal. 1998: 192).

The decision by Cochiti leaders to move their village from their home near the Rio Grande River to the mesa would not have been taken lightly. Life on the mesa would have been quite difficult, in part because of the daily need to carry up water from the stream below. Several Cochiti stories relate these difficulties, emphasizing both the rigours of travel as well as the ever-present danger from enemies (Benedict 1931: 189). The decision to move onto the mesa was likely an attempt to start over, to flee a home that had become polluted by the deaths of the mission priests and the burning of the church, and to build a new community that conformed to the ‘laws of the ancestors’. Following the revolt, Po’pay and Catiti made a grand inspection tour of the pueblos. They instructed the people to cast off Spanish customs and practices and embrace their traditions, as when they came out of the lake of Copala (Hackett and Shelby 1942: 246-7). This account, emphasizing the mythic time of emergence, is clear evidence of a popular revitalization discourse incorporating aspects of nativism and revivalism (Liebmann 2006; Preucel 2002, 2006). Here, time and space converge as the Pueblo people literally recreate their world.

The Cochiti cacique likely planned the location of the village and entrusted specific work groups with the task of building room blocks and excavating the kivas. The homes of the ritual leaders may have been constructed first, followed by those of the villagers, and then the ritual structures. The construction of a new village enabled traditional social relations to be renewed. Perhaps the most fundamental of these relations is the moiety structure. At Cochiti, there are two kiva groups or ‘sides’ known as Turquoise and Pumpkin (Lange 1990: 389). This is paralleled at most of the other Keres villages. These dual divisions serve as exog-amous social groups and facilitate the balance of political and religious power within the village since officials are to be appointed from alternate moieties each year. Hanat Kotyiti was laid out with two plazas each containing a kiva to embody and reproduce the moiety structure (Fig. 13.4). The westernmost kiva likely belonged to the Pumpkin moiety and the easternmost kiva to the Turquoise moiety, on the basis of ethnography analogy to the modern Cochiti Pueblo (Lange 1990).

There is some intriguing historical information on the relative significance of the two kivas. On his second visit to the village in 1693, Vargas remarked on ‘the main plaza’ (Kessell et al. 1995: 200), and a year later he stated that he incarcerated the prisoners in the ‘main kiva’ (Kessell et al. 1998: 194). This reference to a main plaza and kiva might simply refer to size characteristics (the east plaza is slightly more than twice the size of

Fig. 13.4. The two plazas of Hanat Kotyiti (photo: Robert Preucel)

The west plaza), but it may also refer to the social meaning of these features.

The houses of the cacique and other religious leaders were larger than average to accommodate ritual practices and storage. Three of the six room blocks (RB 3, 5, and 6) contain extra-large room suites that were very carefully constructed of unusually large tuff blocks and exhibit some of the finest masonry at the village. They may have been used by the leaders of specific religious societies, such as the Shi’kame, Snake, or Giant societies, all known ethnographically at Cochiti (Lange 1990). However, ritual leaders may have occupied some of the smaller rooms as well. For example, Room 44 in RB 2 may have been occupied by a rain priest since Nelson found ritual paraphernalia associated with rainmaking ceremonies (Preucel 2000a).

Hanat Kotyiti is composed of six room blocks, two of which (RB 1 and RB 2) are joined together. It is likely significant that modern Cochiti is also divided into six sectors. These are named Ha’ni satyu (‘East Group’), Gi’ti satyu (‘North Group’), Po’ni satyu (‘West Group’), Kwi’ satyu (‘South Group’), Ko’lash kule (‘Round Mesa’), and Ka’ katche (‘Plaza Group’) (Lange 1990: 48). The room blocks at Hanat Koytiti certainly would have been named, possibly with some of the same names.

There is historical and architectural evidence regarding the village’s construction sequence. When Vargas first visited the village on 21 October 1692, he noted that:

The Keres Indians had set up a large cross and arches. All the people of the pueblo were a musket shot away. I received them with all kindness, and they greeted me saying the Praised be. I walked to the pueblo’s plaza, which has three cuarteles and another large separate one, where they had prepared a house for me. (Kessell and Hendricks 1992: 515)

The three cuarteles are likely RB 2, 3, 5, and the large separate one is likely RB 6 for reasons discussed above. If this interpretation is correct, RB 1 and 4 were constructed sometime after 1692. Significantly, the bonding and abutment data reveal that both of these room blocks were built in multiple, rather than unitary, building episodes.

The historical record also provides valuable information on the leadership of Hanat Kotyiti and the identity of some of the refugees joining the village. Vargas indicates that El Zepe was the leader of the Cochiti people and identifies Mateguelo as his lieutenant (Kessell et al. 1998: 30, 200,248, 771,823). El Zepe, unfortunately, is not well documented in the historical accounts. We do know that he welcomed a contingent of people from Ya tse (San Marcos Pueblo) led by Cristobal (Kessell et al. 1995: 409, 425) and a group of people from Katishtya (San Felipe) (Kessell etal. 1995: 200; White 1932: 9). However, tensions quickly emerged and El Zepe eventually ordered Cristobal and Zue, his brother, to be put to death because of their pro-Spanish leanings (Kessell et al. 1998: 200). Perhaps because of this event, some Katishtya people subsequently left to found the mesa village known as Old San Felipe or Basalt Point Pueblo along with local Spanish settlers (Harrington 1916: 498, Lange etal. 1975: 69).

Vargas also identifies Antonio Malacate as one of the leaders of the village (Kessell etal. 1995: 404, 540; Kessell etal. 1998: 30, 53, 67). Malacate, the governor of Zia Pueblo, is one of the most famous of the post-Revolt leaders. Serendipitously, he was absent from Zia in 1689 when Domingo Jironza Petriz de Cruzate attacked and burned his village (Kessell etal. 1995: 113, 117, 201). The Zia people that survived established a new mesa village on Cerro Colorado in the Jemez Valley (Kessell etal. 1995: 117). Malacate subsequently left Cerro Colorado to join the Cochiti at Hanat Kotyiti and assist in their resistance.

To restore the Keres world, the Cochiti cacique (probably not El Zepe, since the Spanish term him their captain and governor) may have modelled the village as Kasha K’atreti (White House). Kasha K’atreti was the primordial village of mythological time, built immediately after the emergence of people from the underworld (Ferguson and Preucel 2005). Stevenson (1894: 57-8) provides ethnographic evidence of the Zia people building a village in the form of White House. While it is impossible to know if this story dates to the time after the Pueblo Revolt when mesa villages were being established throughout the Rio Grande, it clearly indicates a relationship between mythology and architecture. If our interpretation is correct, then the Cochiti people physically restored their world through architecture, thereby presencing a past in the active shaping of the future. The shape and layout of Hanat Kotyiti would have re-established a moral order linked to the Revolt-period discourse about living according to the laws of the ancestors. It would have channelled people’s movements through specific gateways and into the plazas and, in the process, reminded them of their connections to a pre-Spanish world and their ancestral way of life.

As discussed above, Hanat Kotyiti attracted a number of refugees seeking to join with the Cochiti people for protection. In some cases the new arrivals would have had family or social relations with the Cochiti people and been invited to join room blocks in the plaza pueblo. This might explain some of the room blocks and the room suites added at the ends of several room blocks. However, in other cases, their family or social relations with the Cochiti may have been attenuated or nonexistent. Because of this, some families may have been directed to build their community apart from the village. The rancheria, located some 200 m east of the plaza pueblo, was either built as part of this process or slightly later during the Second Pueblo Revolt of 1696. The pottery evidence is somewhat inclusive since glazewares of the same historic period are present at both the rancheria and the plaza pueblo. The only exception to this is the greater proportion of Tewa grey - and blackwares at the rancheria that could index Tewa refugees. Juan Griego, an influential Oke owinge war captain, who fought alongside the Cochiti against Vargas, likely joined the community with some people from his village (Kessell et al. 1998: 206). It is also possible that the rancheria was built in 1696 when Lucas Naranjo of Cochiti led his people back up to the mesa (Espinosa 1988: 51). Vargas notes that the Cochiti and Santo Domingo people had their rancheria ‘in the heart of the sierra, which is opposite their pueblo on the mesa’ (Kessell et al. 1998: 819).

For the Cochiti people, Hanat Kotyiti is much more than a mesa containing a collection of archaeological sites. It is a venerated place where their ancestors reside; it deserves respect and requires appropriate behaviour on the part of all people, Pueblo and non-Pueblo visitors alike. It is recalled as one of the ancestral villages mentioned in oral narratives and described in the southward journey of the Cochiti people from Frijoles Canyon in Bandelier National Monument to their current village along the Rio Grande (Lummis 1897:133-54). Each summer, the Cochiti Summer Language programme organizes a day trip to the mesa to acquaint Cochiti youth with this ancestral place. In 2003, part of the mesa was returned to the Cochiti as part of a land exchange with the State of New Mexico. In a press release, Governor Simon Suina says, ‘Cochiti mesa was our forefathers’ land and we are happy to get it back for our future generations’ (New Mexico State Land Office 2003).

13.4 THE POWER OF PLACE

Places exist within a delicate tapestry of social relationships and obligations. With the arrival of the Spanish colonists in 1598, these relationships were systematically disrupted. Juan de Onate physically displaced the people of Oke owinge from their village at Yungue owinge to appropriate it as the base for his fledgling colony (Ellis 1989). During the governorship of Juan Manso, the people of Sevilleta Pueblo were relocated to Alamillo Pueblo so that the Franciscan friars might more easily convert them and monitor their behaviour (Scholes 1942: 29). These, and some forced dislocations due to introduced diseases like smallpox, made it impossible for Pueblo people to maintain their obligations to their ancestors. By 1640, less than a third of the 150 pueblos occupied when Onate arrived were still inhabited (Gutierrez 1991: 113). To compound matters even further, the Spanish friars actively suppressed the primary way in which Pueblo people collectively honour their ancestors, namely by ceremonial dancing. For example, in 1661, Fray Alonso de Posada, the new custodian of New Mexico, issued an order forbidding dancing and requiring the friars to collect and burn all dance regalia (Scholes 1942: 98). It is reported that more than 1,600 masks, prayer sticks, and figures of various kinds were quickly gathered from the kivas and destroyed. These acts, in addition to forced labour, slavery, usurious taxes, and the sexual violation of Pueblo women, led to specific revolts and uprisings that culminated in the famous Revolt of 1680.

Nowhere was the influence of the Spanish colonial project on Pueblo people’s sense of time more evident than at the mission villages themselves, where the sound of the church bells regulated everyone’s activities (Hodge et al. 1945: 101-2). Every morning at dawn, a bell would call the children to church. There, they would be instructed in reading, writing, and singing. Then another bell would call the rest of the villagers to Mass. After receiving the day’s lesson, the people would go home for a day’s work and return at dusk for vespers. Fray Alonso de Benavides drew an analogy between the working of the church and those of a clock: ‘all the wheels of this clock must be kept in good order by the friar, without neglecting any detail, otherwise all would be lost’ (Hodge et al. 1945: 102).

This refashioning of time occurred throughout the Americas. As the Aymara archaeologist Carlos Mamani Condori (1989: 54) has observed, the Spanish colonization of Bolivia resulted in the loss of time, that is, power over history, but not over space. He explains that one of the ways that the Aymara people think of their resistance to the rupture caused by Spanish colonialism is through mythic thought and the attempt to reunite time and space in pacha. The concept of pacha stands in stark contrast to notions of time employed by most archaeologists. It is a concept that sees time as a continuum rather than absolute or artificially segmented into history and prehistory. Yet, as our example of the importance of place in the Pueblo world testifies, indigenous notions of time not only differ from those employed by archaeologists, they represent barriers to understanding the close relationship between time and place that underlies much of Pueblo belief. Pacha not only provides an alternative perspective on time, it also returns control over the production of history to the people who have shaped it and memorialize it.

One of the most distinctive aspects of the post-Revolt period is the wholesale movement of Pueblo peoples from their mission villages to the mesas. We have focused our narrative here on Cochiti Mesa in the Keres district and Tunyo in the Tewa district. However, this same pattern can be seen up and down the Rio Grande at Guadalupe Mesa and San Juan Mesa in the Jemez district, at Cerro Colorado, Canijlon Mesa, and Old San Felipe Mesa in the Keres district, and at Dowa Yalanne (Corn Mountain) in the Zuni district (Liebmann et al. 2005). In each of these cases, the new mesa villages were inhabited by people from several different home villages. This variety must have led to considerable social reorganization and possibly new leadership structures based upon alliances. At Zuni, for example, the six Zuni villages consolidated on Dowa Yalanne (Ferguson 1996a, 2002). At Tunyo, seven Tewa and two Tano villages joined together. At Cochiti Mesa, people from three different Keres villages lived together. There is no question that these moves were motivated, in part, by defensive purposes. However, these mesas must be understood as more than military redoubts. They were and are today sacred places that played critical roles in restoring the Pueblo Indian moral landscape in the aftermath of the Revolt. Their ongoing meanings are literally anchored in place by past events and future experiences and, because of this, they are resources that can be continually drawn on by Pueblo people to instil pride and provide cultural continuity.

After the Spanish Reconquest, most Pueblo people moved off their sacred mesas. In some cases, they reoccupied their mission homes, while in other cases they decided to join permanently with their hosts. In other cases, they built new villages in new locations. For example, the Zuni went up to Dowa Yalanne as six separate villages but they came down and re-established themselves as a single village at Halona:wa. The Tewa came down from Tunyo to re-establish Powhoge, Kha’po, Nanbe, and Tesugeh. However, the people of Kuyemuge, Sakona, Yam p’hamba, and Ipere reoccupied their villages only briefly. The latter two villages moved north and established two new villages in the Espanola Valley and eventually moved west to found the village of Hano on First Mesa (Dozier 1966). The Keres came down from Hanat Kotyiti to re-establish themselves at Cochiti Pueblo. The people of Ya tse, who had joined with them apparently never reoccupied their home village. The people of Katishtya were not part of this resettlement since they had previously come off the mesa to join with their pro-Spanish relatives at their own mesa village known as Katishtya shoma (Old San Felipe) built sometime between 1683 and 1693 (Harrington 1916: 498). Only Haaku (Acoma) and the Hopi remained on their mesas where they had lived prior to the Revolt. The sacred mesas are visual testimony to Pueblo people’s settlement history. But, more importantly, they provide access to their ancestors and deities and are accordingly a powerful reminder of their sovereignty. The move off the mesas was thus the last major shift before the refounding of the villages in the locations where they exist today.

13.5 LIVING THE LEGACY OF THE PUEBLO REVOLT

The Pueblo Revolt occupies a central place in contemporary Pueblo Indian historical consciousness (Liebmann and Preucel 2007). In 1980, the Pueblos joined together and commemorated its tercentennial anniversary. Their goals were to provide a focus for Pueblo people to examine their heritage and to reaffirm their beliefs and values; to further a broader understanding of Pueblo culture by promoting cultural identity, human dignity, and social viability; to draw attention to the unique issues and concerns of Pueblo communities; and to clarify issues that structure Pueblo and non-Pueblo relations (Agoyo 2005: 95). On 18 July, representatives from most of the Rio Grande pueblos plus the Hopi and Ute travelled to Oke owinge. For the next two days, Pueblo people performed a series of dances to honour their ancestors and history. There was an outdoor Mass presided over by Archbishop Robert Sanchez held in the north plaza of the village. The Mass also honoured Kateri Tekawitha, the Mohawk woman, now canonized as a saint, who died in 1680. The following day, the second annual Po’pay run was held to commemorate Omtua’s and Catua’s run.

In 1997, the Pueblos again joined together to sponsor the Po’pay Statue Project. Herman Agoyo and other Pueblo Indian leaders petitioned the New Mexico State Legislature to select Po’pay as the subject of the state’s second statue to be installed in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol Building (Agoyo 2005). The legislature agreed and created the New Mexico Statuary Hall Commission to raise the necessary funds. A competition to sculpt the statue was held and, in 1999, Clifford Fragua of Walatowa (Jemez Pueblo) was awarded the commission. He chose to carve it from pink Tennessee marble to better represent the texture and colour of Pueblo Indian skin (Fig. 13.5). According to Fragua, the bear fetish in Po’pay s right hand stands for Pueblo religion, which is the core of the Pueblo world. The water jar symbolizes Pueblo culture, and the deerskin robe is a symbol of his status as a hunter and provider. The shell necklace is a constant reminder of the sacred lake where life began. His back is scarred by the whipping he received from the Spaniards in the Santa Fe plaza for his participation in Pueblo ceremonies. On 21 May 2005, the statue was unveiled at Oke owinge and placed in the rotunda in Washington, DC, on 22 September 2005.

The Po’pay Statue Project has given rise to a series of spinoff projects designed to feature Po'pay and promote the incorporation of the Pueblo

Fig. 13.5. Po’pay statue in National Statuary Hall, US Capitol, Washington, DC (photo: Robert Preucel)

Revolt into American history (<http://www. nativeart. net/affilpopay. php>). The projects currently under way or in the planning stages include a documentary entitled 'Po’pay, A True American Hero’, which presents the story of the Po’pay Statue Project, ‘In the Spirit of Po’pay, an educational website featuring information about Po’pay and other influential leaders, and 'Po’pay, The Motion Picture’, a big-budget action film about Po’pay and the Pueblo Revolt narrated from Rio Grande Pueblo and Hopi perspectives. In addition, the project has planned ‘The Knotted Cord Tour’, an international touring event promoting language and cultural preservation, renewable energy sources, environmental protection, and sustainable living. This tour also includes ‘The Knotted Cord Documentary’, a feature-length documentary film to be made by young people on the Knotted Cord Tour to honour the visionary leaders among the cultures they visit.

13.6 CONCLUSIONS

The place-based approach advocated here extends the historical approaches to the post-Revolt period by considering Pueblo perspectives on time, space, and history. Southwestern historians and archaeologists have traditionally interpreted the abandonment of mission villages and the establishment of new villages on specific mesas following the Revolt of 1680 as a defensive strategy. This view is only partially correct. These mesas are revered as powerful places in the sacred Pueblo geography because they are the sites of mythical encounters with supernatural beings. Similarly, the organization and layout of pueblo villages are not simply responses to environmental considerations. They also embody the values and beliefs of the people who constructed and lived in them. According to this view, the building of new villages on sacred mesas, the orientations of the room blocks, the placement of the kivas and shrines, the entryways into the plazas, and the trail network are all part of how the Pueblo world was restored following the Revolt.

We have drawn our inspiration from contemporary Pueblo perspectives that emphasize the mutual obligations of places and people as giving rise to a moral landscape, one that simultaneously constructs personal identity and ensures cultural survival. More specifically, we seek to emphasize the ontological status of place—how place and people bring each other into existence. This indigenous approach shares some similarities with recent landscape perspectives that highlight phenomenological experience (Snead 2008). However, it seeks to bring out the distinctiveness of Pueblo lived experience in the same manner that peoples of North America (see Gould, Mrozowski, this volume), Africa (see Land, Schmidt, Walz this volume), and India (see Rivzi, this volume) seek to do, rather than dwell on the general characteristics of universal experience. Significantly, an indigenous approach challenges the standard time-based perspective of southwestern archaeology, which only perpetuates the artificial history/prehistory divide.

For Pueblo people, the sense of obligation and responsibility embodied in the phrase, ‘living in accordance with the laws of the ancestors’, underlies the wholesale movement of Pueblo peoples from their mission villages to the sacred mesas during the post-Revolt period. This sense of ‘right living’ still structures people’s relationships to these sacred mesas to this day. If we are to understand more fully the Revolt and Reconquest period, which has been long dominated by historians of the Spanish borderlands, it is necessary to consider the Pueblo motives and beliefs that enabled the restoration of their world and that persist up to the present. As Governor James Hena of Tetsugeh put it, ‘The Pueblo people would not be here if it were not for the revolt of 1680. We would have lost our culture and disappeared’ (Pember 2007).

World History

World History