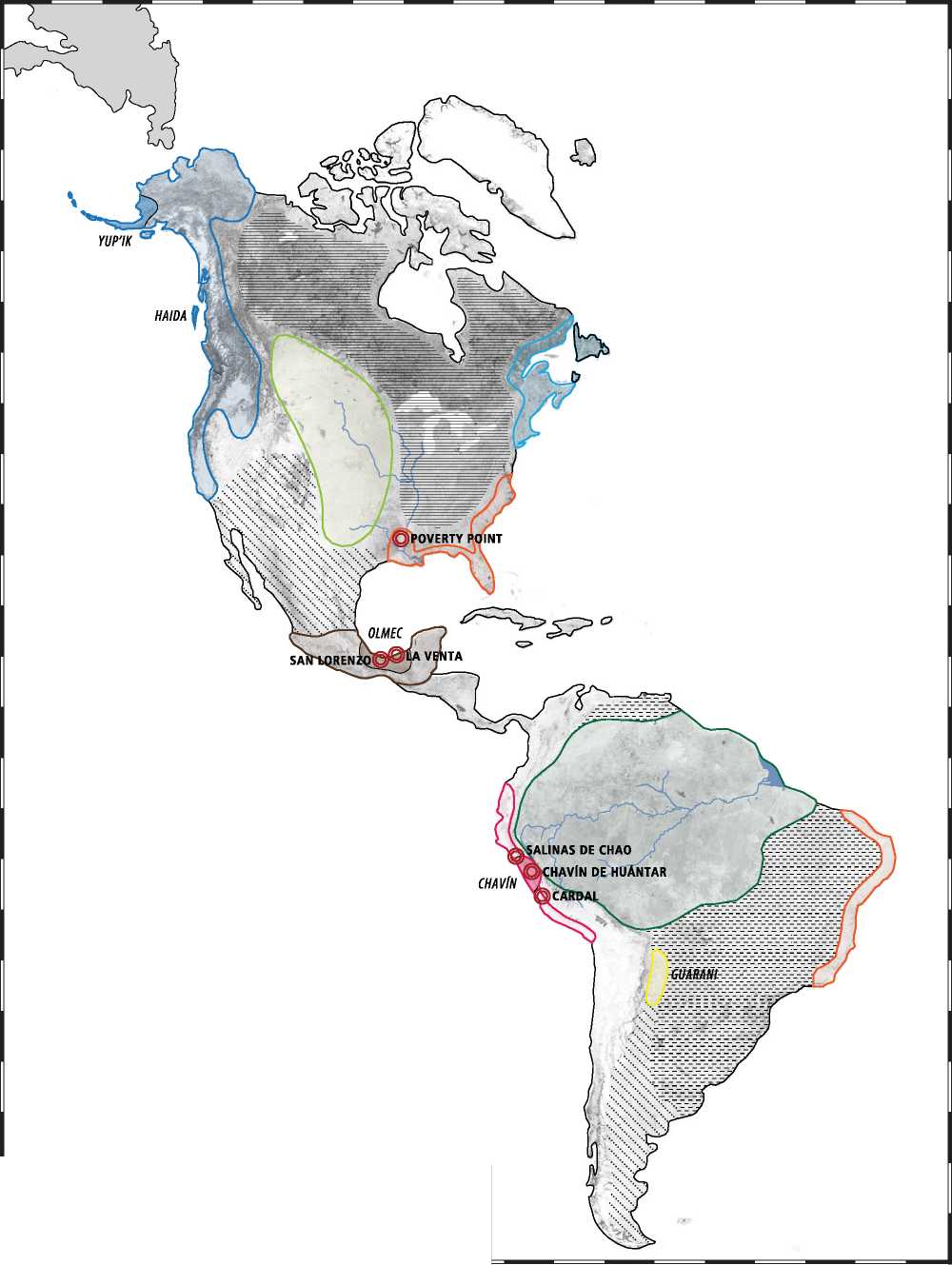

The history of the Amazon cultures is still cloudy, buried largely in the roots of the rainforest. But it is now clear that Amazon cultures were once a more formidable presence than had been thought.31 Since they did not build in stone, post-conquest depopulation allowed the forest to restore itself. So today, when drawing a map of the Incas, and instead of seeing literally nothing in Brazil, one should imagine a 3,000-kilometer-long C-shaped ring of forest-based cultures from Bolovia in the south, stretching up through eastern Peru to Columbia and curving eastward to southern Venzuela, all of which in turn traded with lowland rainforest cultures of the Amazon in central and eastern Brazil. In the sixteenth century, at the time of the Spanish Conquest, the east-west connections across the continent would have been just as important as the north-south connections controlled by the Inca.

Among the remnants of various rainforest people, there are the Yanomami (“people”), whose contact with non-indigenous societies over the most part of their territory has been relatively recent.32 Their territory once covered an area of approximately 192,000 square kilometers and was located on both sides of the border between Brazil and Venezuela. The Yanomami still number around 26,000 people. The area is a forested highland surrounded by rainy lowlands to the north and south. The weather in this region is milder than in the lowlands and malaria is less prevalent, water is abundant, and the forest soils productive.

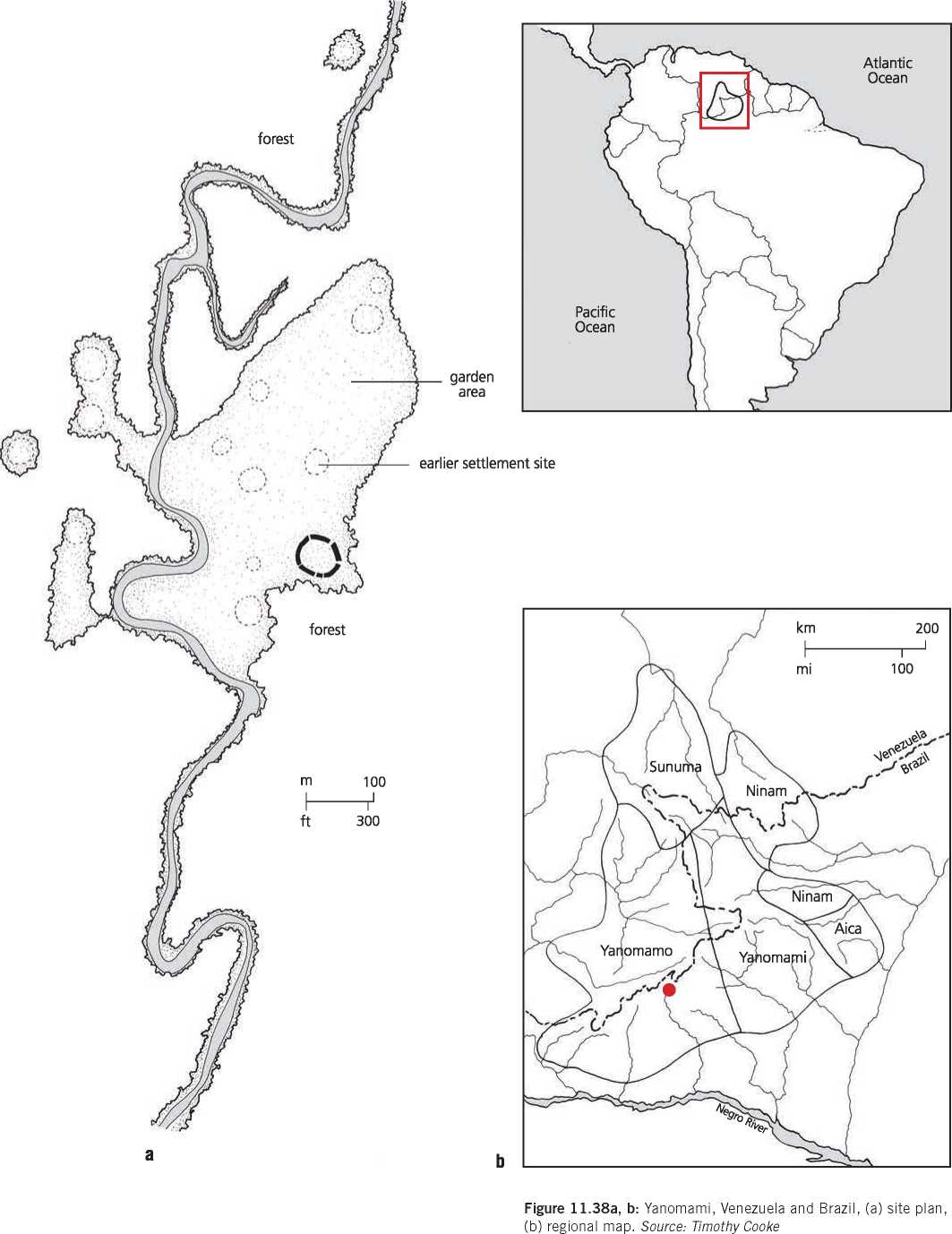

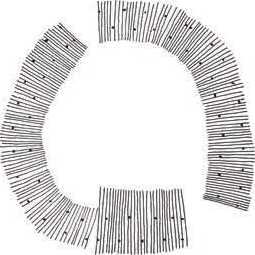

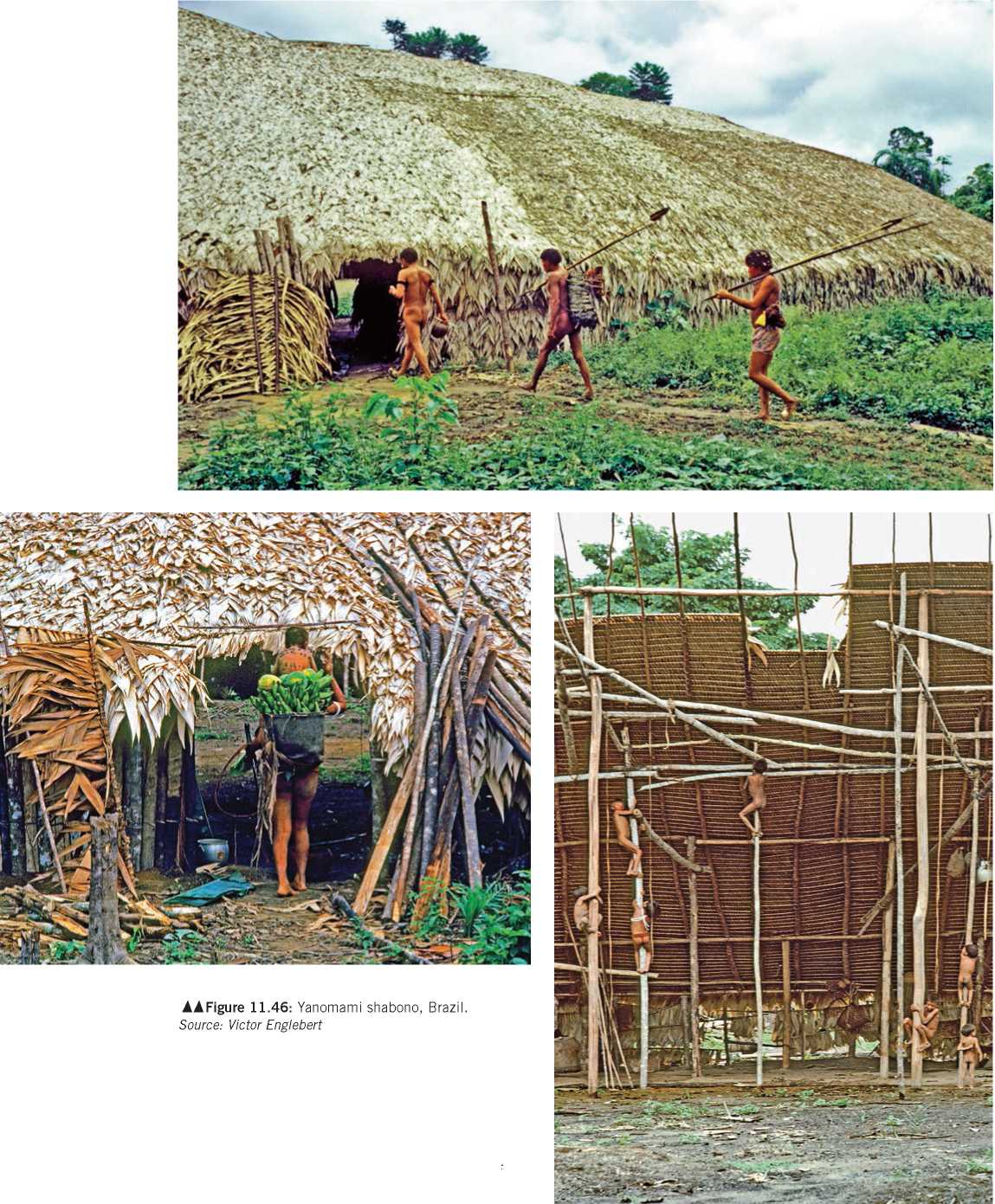

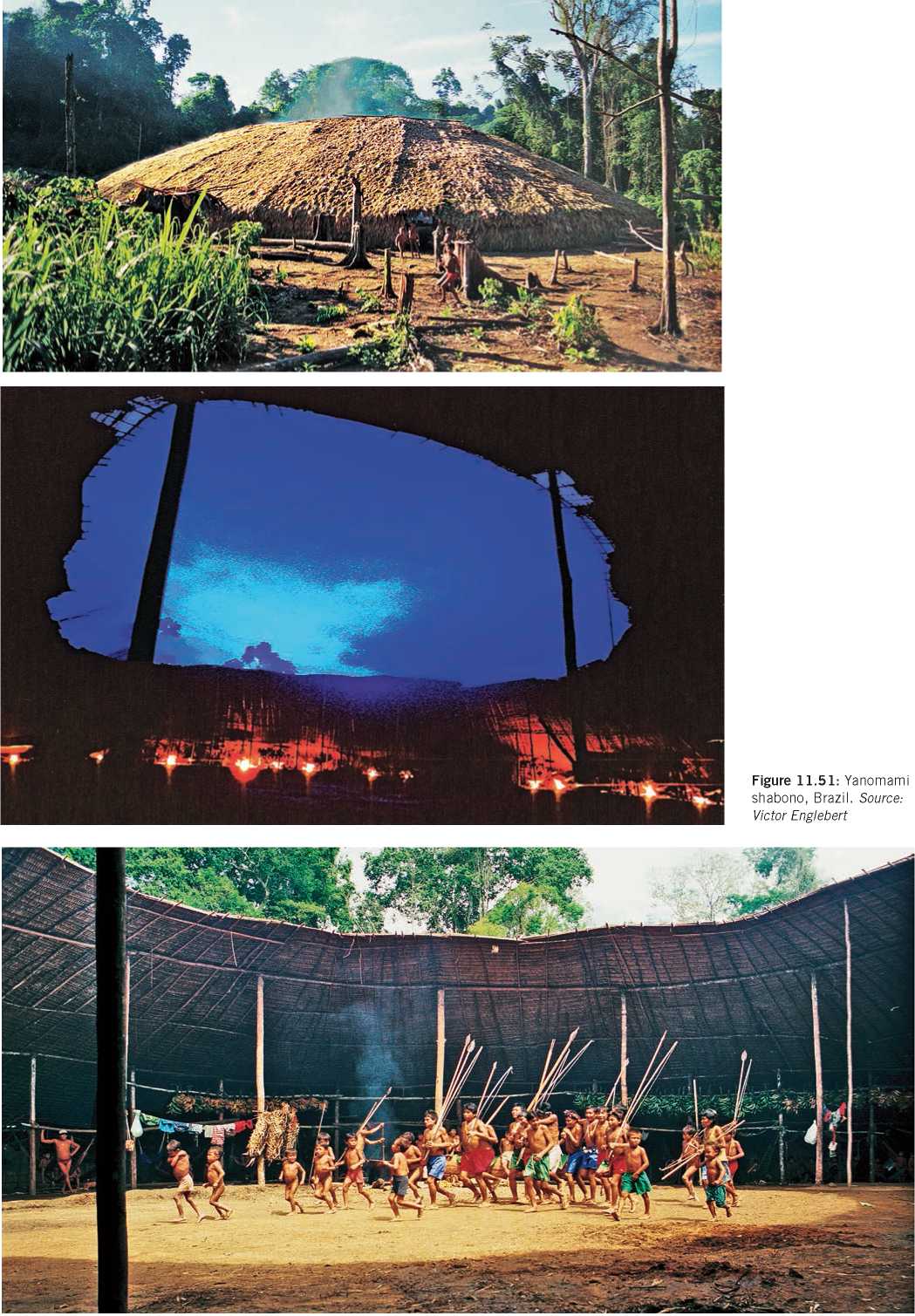

Each collective house or village is an autonomous economic and political entity (kami theriyamaki, “we co-residents”); its members prefer to marry inside this community of kin. Despite this self-governance, a network of relations of matrimonial, ceremonial, and economic practices are maintained with nearby groups forming a complex sociopolitical nexus, linking the totality of Yanomami collective houses and villages from one end of the indigenous territory to the other. The communal house, or shabono, is built when certain groups break ofi on their own in congregations of about sixty to eighty people. The linkages between the clan members occupying a shabono are thus based on blood and marriage—meaning that each shabono constitutes a microcosm unto its own, yet is closely bound by kinship ties with numerous other shabono (Figures 11.38a, 11.38b, 11.39, and 11.40a, 11.40b).

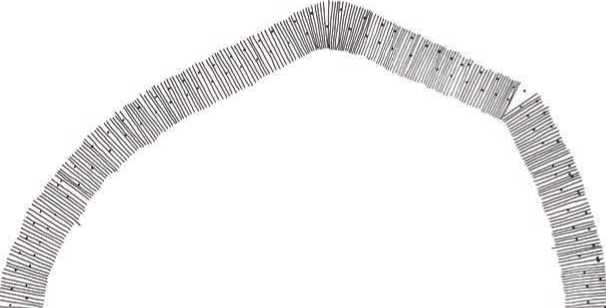

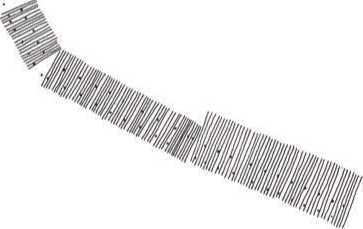

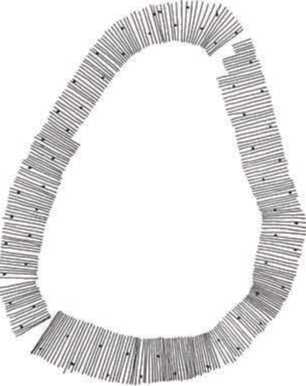

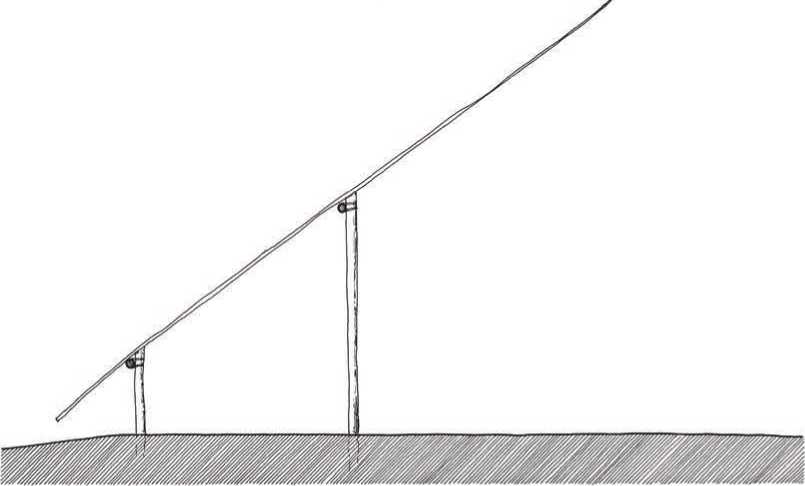

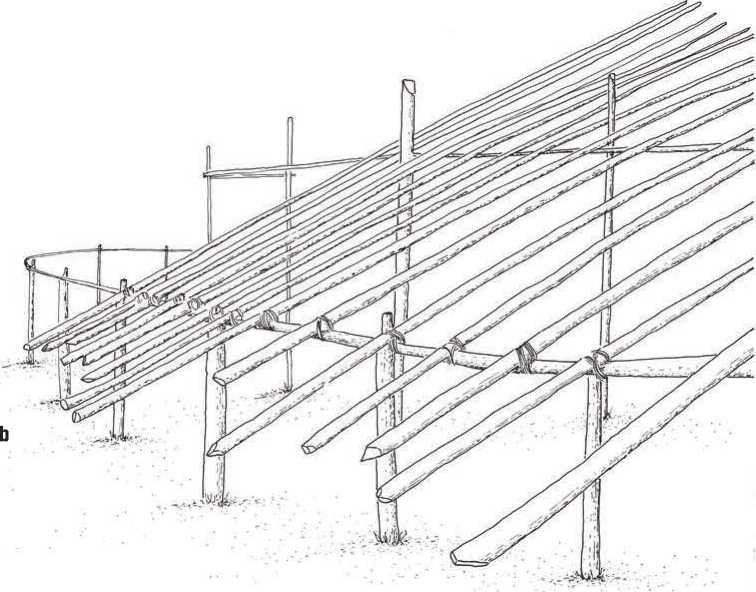

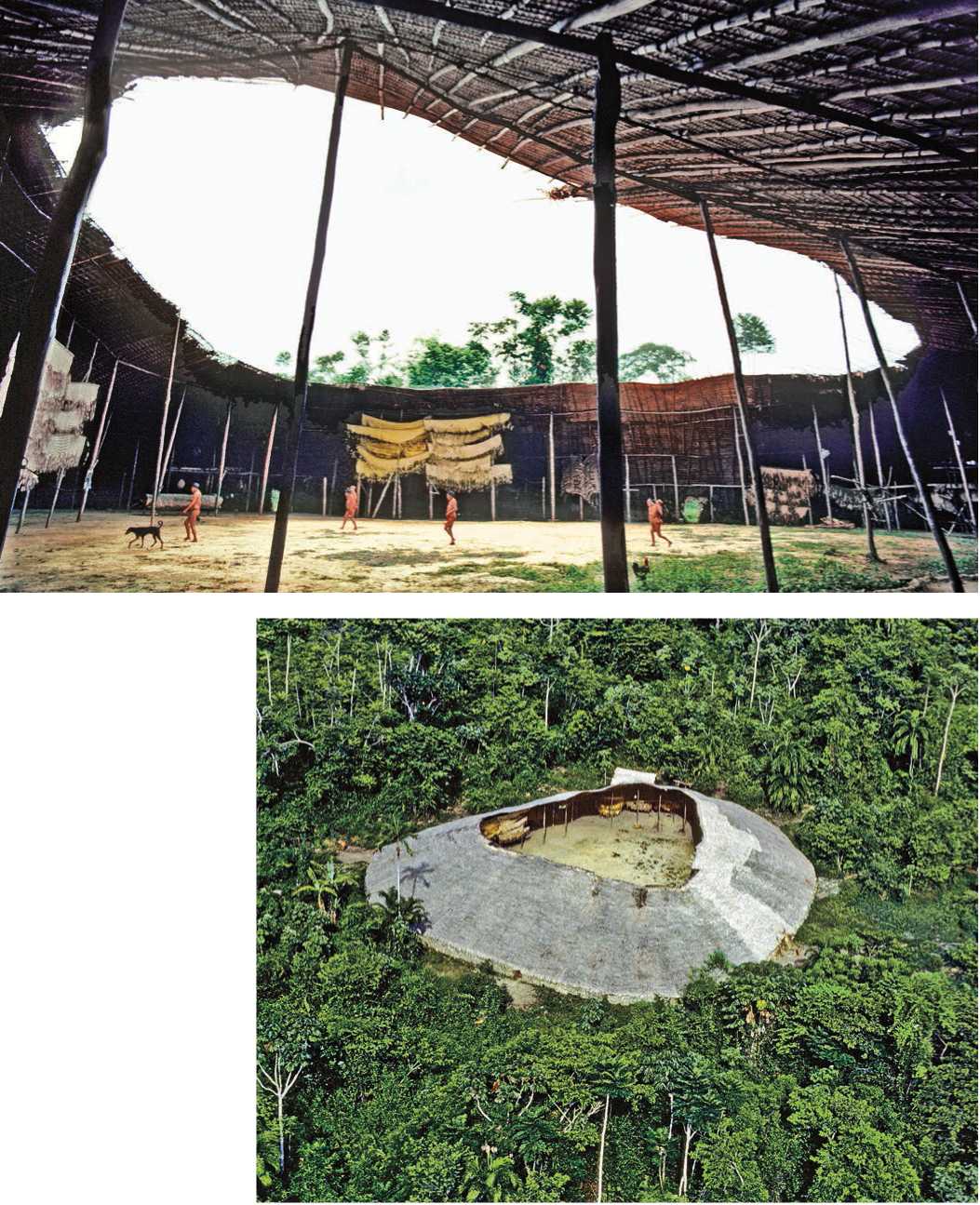

The shabono are designed in circles or ovals around an open courtyard. Construction is in the manner of a lean-to, tall and open to the center and close to the ground at its perimeter. Framing consists of hardwood poles lashed together with liana. Thatching is palm. Sleeping hammocks are latched to the structure’s support poles. The house is protected by an 8- to 10-foot-high palisade of logs and poles set vertically a few inches into the ground. These make the house safe from incursion from arrows and are in various states of repair depending on circumstances. Each family has its own well-deAned place and hearth. Here people conduct their crafl: activities, paint their bodies, rest, or have quiet conversations. At night, the Are circles illuminate the structure from within.

Figure 11.39: Yanomami, Venezuela and Brazil, three typical plans. Source: Timothy Cooke/ Graziano Gasparini and Luise Margolies, "La Vivienda Colectiva de los Yanomami,” Tipitf: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2 (2004): 98

Figure 11.40a, b: Yanomami, Venezuela and Brazil: (a) section, (b) view. Source: Timothy Cooke/Graziano Gasparini and Luise Margolies,

"La Vivienda Colectiva de los Yanomami,” Tipitf: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2 (2004): 111; Napoleon A.. Chagnon, Studying the Yanomamo (New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1974), 258

Figure 11.42: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Victor Englebert

Figure 11.41: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Victor Englebert

The central space is known as the heha and its size depends on the number of the community. In the heha, visitors exchange gifts and the inhabitants perform their ritual dances. But it is also the space for cooking and where children play. Climate plays a part in determining the size. In Sierra Parima near the border with Brazil, it will be smaller and almost closed over, with a round hole in the center. The thick leaves of banana that are left hanging from the roof edge and reach almost to the floor ofier protection against the cold (Figures 11.41 and 11.42).

Construction of the shabono requires the coordination and collaboration at the community level. It may last several months because men alternate this work with their other activities. Women also participate, collecting and carrying materials, but the men build the structure, working their way upward into the heights, binding poles together as they go. Different trees are used for different purposes. During most of the year, Yanomami remain in the shabono, but during the dry season between November and March, the members of the shabono will undertake lengthy tours to collect wild fruits, hunt, or visit relatives in other communities. During these treks, the Yanomami will build informal wind screen s33 (Figures 11.43, 11.44, 11.45, 11.46, 11.47, 11.48, 11.49, 11.50, and 11.51).

Figure 11.43: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Victor Englebert

Figure 11.44: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Victor Englebert

Figure 11.45: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Victor Englebert

A Figure 11.47: Yanomami shabono, Brazil Source: Victor Englebert

Figure 11.50: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Victor Englebert

Figure 11.49: Yanomami shabono, Brazil. Source: Rogerio do Pateo

After about two years, the shabono begins to leak and becomes infested with insects. It might be burned or abandoned with a new one built nearby. When the garden soils of the area have been depleted after a decade or so, the area will be abandoned altogether and a new territorial perimeter established. The space of the forest used by each Yanomami house-village can be described as a series of concentric circles. The first, within a 5-kilometer radius, circumscribes the area of immediate use by the community: small-scale female gathering, individual fishing (or, in the summer, collective fishing with timbo poison), brief hunting trips (at dawn or dusk), and agricultural activities. The next circle, within a 5- to 10-kilometer radius, is the area of individual hunting and day-to-day food gathering. The third circle, within a 10- to 20-kilometer radius, is the area used for collective hunting expeditions, which last one to two weeks and which precede funerary rituals.

As with the Shuar, there is no such thing as a “natural” death for the Yanomami. A shaman is thus responsible for making sure that the rituals of death are performed properly, in which case the deceased will enter a world much like this one, but far more agreeable. A hot and terrible place is reserved for those who are selfish and stingy in life. The body is cremated, along with personal belongings. The bones are pulverized and placed in gourds, which are distributed to kinsmen, who value them as prized possessions. The powder is used in the preparation of a drink that is consumed in a sorrowful ceremony that can be repeated long after the death.

The Waimiri-Atroari people, who live to the south of the Yanomami, have a similar architectural expression. They too construct a circular mydy taha, “big house.” The term also designates the space that makes up the village, both the living quarters and its immediate surroundings, including the gardens. The mydy taha serves, of course, as a ritual space during their festivities. New villages are founded according to the community’s needs, such as an increase in the population, the exhaustion of garden soils, or a scarcity of game.34

In the central Amazon area, there are a number of tribes who build their villages out of rectangular houses in a circular arrangement around a large open space where ceremonies are held. The house, on the other hand, is a relatively dark and private place even though it is not divided; it is usually the domain of the women and children, whereas the plaza is usually seen as the domain of the men. The area of the Xingu River which contains the Xingu, Waura, Kuikuro, and Kamayura villages, consists of open longhouses about 25 meters long and 15 meters wide with doors at opposite ends. The hammocks, which are made by women, are woven of native cotton mixed with the fibers of palm tree sprouts. Hammocks are hung around the outer part of the house so as to leave the central area a free space. Each longhouse has one chief or head that is responsible for the economic activities of the group. The chief of the house is the one who leads the others in the fields, overseeing the cleaning of the land and the planting.35 For the Kuikuro, each house has its “master” or oto, the man who built the home and brought his family group together around him. The gardens also have a “master,” a man or woman who has responsibility for and commands the work of clearing the forest, preparing the ground, and planting. Festivities also each have their “masters,” the person who sponsored its organization in accordance with the wishes of the village on that specific occasion. To be “master” of a festivity signifies having the capacity to mobilize family and collective labor for the production of large quantities of food and to pay for the various types of services.36

Not too far away are the Kamayura who also follow the upper Xinguan model, except that their houses have a rounded roof that reaches to the ground. From their “plaza,” hoka 'yterip, toward which all trails emanate, there is one path that connects to the house of the flutes (tapuwi), crossed over the middle by the “path of the sun.” The flutes, which play an important role during ceremonies, can only be seen and touched by men. In front of the house of the flutes and facing to the east, there is the bench for the smokers’ circle, where the men get together to tell about the happenings of the day or to discuss specific subjects—such as the preparation for a collective fishing expedition, participation in the building of a house, collective cleaning of the plaza, or preparation for an upcoming festival, among other things.

The center for information, public place, social and masculinity par excellence, the plaza is the place where official messengers from other villages are received with public discourses,

Figure 11.52: The Americas, 1500-800 bce. Source: Michael Kubo

Where the wrestling matches, intergroup ceremonies, and the majority of the rituals and festivals of the village itself are held. It is also there that, among the men, food distribution (of fish, beiju, porridge, pepper, and bananas) is done, generally in payment for services rendered (such as on the occasion of a house building or the burning, cleaning, or community planting of a garden), or simply retribution from the “owner” of a festival for those who participated in it. It is even there that the dead are buried. The village is formed by a group of houses, each of which is occupied by a domestic group comprised of a core of brothers, to which are added parallel cousins and eventual members of ascending generations. The leader of this domestic group is the morerekwat (“owner of the house”), who coordinates productive activities and other daily tasks that include the participation of all families. Rules require that in the first years of marriage, the husband should live in the house of his wife’s parents, paying through his services for the concession of their daughter. Having completed this period, the married couple can choose a new residence, which is generally the husband’s house of origin.

The dwellers of a house organize the labor for food production under the coordination of the house owner. Both in the clearing of the garden and in the harvest, work presupposes cooperation among the domestic group, even if each family has its own garden. The men prepare the garden and the women take the manioc out of the soil, extract from it the pulp and starch. Several food products are made from this, including mohete, a thick and sweetened soup. The pulp derived from manioc is stored in a common place inside the house, this being for collective consumption, independent of the participation that each person had in its production. Despite the relative autonomy of individual houses, the entire village is headed by a leader who acts as mediator and regulator of conflicts, maintaining the internal harmony of the group and expressing generosity. The rules of succession to the position of leader of the village are flexible and customarily give rise to much competition for the post37 (Figure 11.52).

ENDNOTES

1. Richard S. MacNeish, “The Preceramic of Middle America,” in Advances in World Archaeology. Vol. 5, eds. Fred Wendorf and Angela E. Close (London: Academic Press, 1986): 123.

2. David C. Grove et al., “Settlement and Cultural Development at Chalcatzingo,” Science 192, no. 4245 (June 1976): 1203-1210; Muriel Noe Porter, Tlatilco and the Pre-Classical Cultures of the New World (New York: Johnson Reprint, 1953).

3. David C. Grove, “Chalcatzingo, Morelos, Mexico: A Reappraisal of the Olmec Rock Carvings,” American Antiquity 33, no. 4 (October 1968): 486-491.

4. Allen J. Christenson, “Places of Emergence: Sacred Mountains and Cofradia Ceremonies,” in Pre-Columbian Landscapes of Creation and Origin, ed. John Edward Staller (Vienna: Springer, 2008): 95-121.

5. Duncan Earle, “Maya Caves Across Time and Space: Reading-Related Landscapes in K’iche’ Maya Text, Ritual and History,” in Pre-Columbian Landscapes of Creation and Origin, ed. John Edward Staller (Vienna: Springer, 2008): 67-93.

6. Olmec is not their real name. It was given to them by modern archaeologists. Their real name is unknown.

7. Michael D. Coe and Richard A. Diehl, In the Land of the Olmec. Vol. 1 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980): 30; David C. Grove, “Olmec Altars and Myths,” Archaeology 26, no. 2 (1973): 129-135; David C. Grove, “Public Monuments and Sacred Mountains: Observations on Three Formative Period Landscapes,” in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, eds. D. C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1999): 255-300.

8. Vincent H. Malmstrom, “The Olmec Dawning,” Www. dartmouth. edu/~izapa/CS-MM-Chap.%205. htm (accessed October 30, 2011).

9. Carolyn E. Tate, “Landscape and a Visual Narrative of Creation and Origin at the Olmec Ceremonial Center of La Venta,” in Pre-Columbian Landscapes of Creation and Origin. ed. John Edward Staller (Vienna: Springer, 2008): 31-65; C. E. Tate and G. Bendersky, “Olmec Sculptures of the Human Fetus,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 42, no. 3 (1999): 303-332. See also, S. Milbrath, “Birth Images in Mixteca-Puebla Art,” in The Role of Gender in Pre-Columbian Art and Architecture, ed. Virginia E. Miller (Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, 1988): 153-178.

10. Carolyn E. Tate, “Holy Mother Earth and Her Flowery Skirt: The Role of the Female Earth Surface in Maya Political and Ritual Performance,” in Ancient Maya Gender Identity and Relations, eds. Lowell S. Gustafson and Amelia M. Trevelyan (Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey, 2002): 281-318.

11. Philip Drucker, Robert F. Heizer, and Robert J. Squier, Excavations at La Venta Tabasco, 1955 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1959).

12. Peter D. Joralemon, “In Search of the Olmec Cosmos: Reconstructing the World View of Mexico’s First Civilization,” Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Edited by E. P. Benson and B. de la Fuente (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1996): 51-59.

13. Bernardo T. Arriaza et al., “Chinchorro Culture: Pioneers of the Coast of the Atacama Desert,” in Handbook of South American Archaeology, eds. Helaine Silverman and William Harris Isbell (New York: Springer, 2008): 45-58; Bernardo T. Arriaza, Russell A. Hapke, and Vivien G. Standen, “Making the Dead Beautiful: Mummies as Art” Archaeology. org (December 26, 1998), www. archaeology. org/online/features/chinchorro/ (accessed August 21, 2011).

14. Bernardo T. Arriaza et al., “Chinchorro Culture: Pioneers of the Coast of the Atacama Desert,” in Handbook of South American Archaeology, eds. Helaine Silverman and William Harris Isbell (New York: Springer, 2008): 56.

15. Elizabeth J. Reitz, “Faunal Remains from Paloma, an Archaic Site in Peru,” American Anthropologist, New Series 90, no. 2 (June 1988): 310-322; Jeffrey Quilter, Life and Death at Paloma, Society and Mortuary Practices in a Preceramic Peruvian Village (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1989).

16. See Frederic Andre Engel, An Ancient World Preserved: Relics and Records of Prehistory in the Andes, trans. Rachel Kendall Gordon (New York: Crown Publishers, 1976): 267-290. David Morales Chocano, “Pacopamp Architecture and Iconography,” William J. Conklin and Jeffrey Quilter (Los Angeles: University of California, 2008): 149. I will spare the reader the complex division of Peruvian history into ages. They are: Pre-ceramic (5000-3000 bce); Late Pre-ceramic (3000-2000 bce); Initial Period (2000-800 bce); Formative Period (800-200 bce); Early Intermediate Period (200 bce to 500 ce); Middle Horizon (500-1000 ce); Late Intermediate Period (1000-1470).

17. D. Cusack, “Quinoa: Grain of the Incas,” Ecologist 14 (1984): 21-31.

18. Alberto Bueno Mendoza and Terence Grieder, “Los Petroglifos de La Galgada/The Galgada Petro-glyphs,” Bolet i n Official de la Association Peruvana de Arte 1/4 (May 2010): 50-52.

19. Terence Griede et al., La Galgada, Peru: A Preceramic Culture in Transition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988); Jonathan Haas and Winfred Creamer, “Cultural Transformations in the Central Andean Late Archaic,” in Andean Archaeology, ed. Helaine Silverman (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004): 35-50.

20. See the excellent book, Michael Edward Moseley, The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization (Menlo Park, CA: Cummings Publishing Co., 1975). Frederic Andre Engel, “Sites et establissments san ceramique de la cote Peruvienne,” Journal de la Societe des Americanistes 44 (1957): 67-155.

21. Stephen G. Bunker, The Snake with Golden Braids: Society, Nature and Technology in Andean Irrigation (Oxford: Lexington Books, 2006).

22. Ruth Shady Solis, “America’s First City? The Case of Late Archaic Caral,” in Andean Archaeology III: North and South. Volume 3, eds. William Isbell and Helaine Silverman (Vienna: Springer, 2008): 28-66; Joyce Marcus, P. Ryan Williams, and Michael Edward Moseley, Andean Civilization: A Tribute to Michael E. Moseley (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, 2009).

23. Donald Ugent, Shelia Pozorski, and Thomas Pozorski, “Archaeological Potato Tuber Remains from the Casma Valley of Peru,” Economic Botany 36, no. 2 (April-June 1982): 182-192.

24. Shelia Pozorski and Thomas Pozorski, “Recent Excavations at Pampa de las Llamas-Moxeke, a Complex Initial Period Site in Peru,” Journal of Field Archaeology 13, no. 4 (Winter 1986): 381-401; Shelia Pozorski and Thomas Pozorski, Early Settlement and Subsistence in the Casma Valley, Peru (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1987).

25. Thomas Pozorski and Shelia Pozorski, “An I-Shaped Ball-Court Form at Pampa de las Llamas-Moxeke, Peru,” Latin American Antiquity 6, no. 3 (September 1995): 274-280.

26. Duccio Bonavia, Mural Painting in Ancient Peru, trans. Patricia J. Lyon (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985).

27. E. Jean Langdon, “Yage Among the Siona: Cultural Patterns in Visions,” in Spirits, Shamans, and Stars: Perspectives from South America, eds. David L. Browman and Ronald A. Schwarz (The Hague: Mouton, 1979): 63-93.

28. Jerry D. Moore, Architecture and Power in Ancient Andes: The Archaeology of Public Buildings (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996): 126; Silvia Rodriguez Kembel and John W Rick, “Building Authority at Chavin de Huantar: Models of Social Organization and Development in the Initial Period and Early Horizon,” in Andean Archaeology, ed. Helaine Silverman (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004): 51-76.

29. Charles S. Spencer and Elsa M. Redmond, “Prehispanic Chiefdoms of the Western Venezuelan Llanos,” World Archaeology 24, no. 1 (June 1992): 134-157.

30. See A. Oyuela-Caydedo, “Late Pre-Hispanic Chiefdoms of Northern Columbia,” in Handbook of South American Archaeology, eds. Helaine Silverman and William Isbell (New York: Springer, 2008): 419422.

31. See for example: Michael J. Harner, Jivaro: People of the Sacred Waterfalls (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

32. William J. Smole, The Yanoama Indians, A Cultural Geography (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1976).

33. Graziano Gasparini and Luise Margolies, “La Vivienda Colectiva de los Yanomami,” Tipiti: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2/2 (2004): 93-130.

34. “Waimiri-Atroari Indians,” Hands Around the World, from Instituto Socioambiental, Http://indi-an-cultures. com/Cultures/waimiri. html (accessed August 24, 2011). See also, William Milliken, The Ethnobotany of the Waimiri Atroari Indians of Brazil (Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens, 1992).

35. Margaret Ann Smith, “The Indians of the Xingu: Cultural Homogenization in the Amazon Rainforest,” Xingu Indians, Www. amazon-indians. org/page16.html (accessed January 25, 2010).

36. Bruna Franchetto, “Kuikuro,” Povos Indigenas no Brasil, Http://pib. socioambiental. org/en/povo/ kuikuro/print (accessed January 25, 2010). See also Robert L. Carneiro, “Recent Observations of Shamanism and Witchcraft among the Kuikuru Indians of Central Brazil,” Annals of the New York Academy of Science 293 (1977): 215-228; Robert L. Carneiro, “Subsistence and Social Structure: An Ecological Study of the Kuikuru Indians” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1957).

37. Carmen Junqueira, “Kamaiura,” Povos Indigenas no Brasil, Http://pib. socioambiental. org/en/povo/ kamaiura/print (accessed January 25, 2010).

World History

World History