The Ganga river, which gives the valley its name, emerges from the icy Gaumukh cave in the central Himalayas and is known at that point as the Bhagir-athi. In its early course, it resembles a mountain torrent, which assumes the name Ganga after its confluence with the Alaknanda river at Devaprayag. After crossing Hardwar, the river flows out of the mountains into the plains that it has helped to create. These plains stretch for hundreds of kilometers and become deltaic in the east of the Indian subcontinent, where the Ganga’s waters enter the Bay of Bengal, combined with those of the Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers. Along the way, the meager river which emerges into the plains becomes majestic and swollen as it receives the waters of major and minor rivers across north India: the Yamuna, Ramganga, Tons, Gomati, Ghaghara, Gandak, Sai, Kali Nadi, Sarayu, Kosi, and their numerous tributary systems. More than 60 percent of the water flowing into the Ganga plains comes from Himalayan sources, while 40 percent comes from the peninsula. Unlike the Indus system where the five Punjab rivers combine to form a united stream, the Ganga system is constantly enriched by tributary rivers as it flows towards the direction of increasing rainfall.

The deeply entrenched river that today makes its way across the north Indian plains is a Late

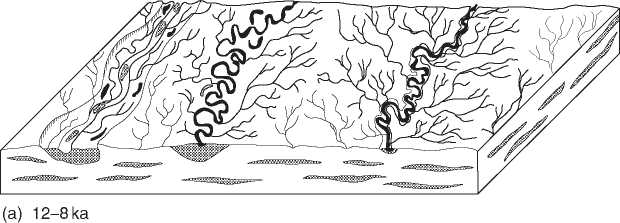

Figure 2 Evolution of the Ganga plain (after Singh 2001-02): (a) 12-8 ka; (b) 6-4 ka, marked by the creation of lakes; (c) 2-0 ka, drying out and siltation of lakes and depressions.

Pleistocene-Early Holocene development (Figure 2). This was when the Late Pleistocene pattern of weak summer and strong winter winds witnessed a shift towards a vigorous southwest monsoon bringing summer rain. Consequently, the Ganga river which used to be a low-sinuosity, shallow braided drainage line, developed its present high-sinuosity meandering channel, cutting deep into its present bed.

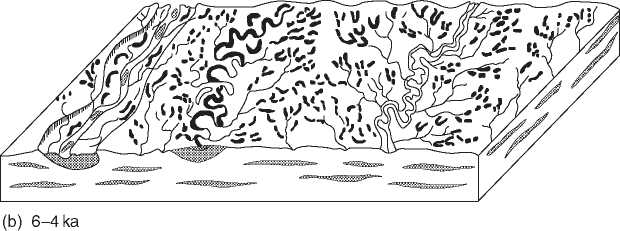

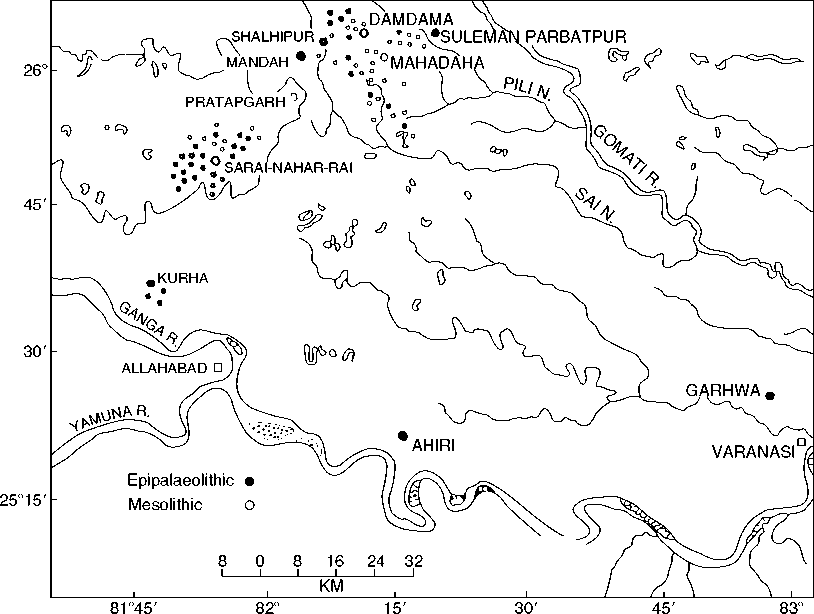

An important hydrographic feature of the middle Ganga plain is the large number of horseshoe lakes or marshy depressions known locally under the name of tal. Apparently, as the Ganga started cutting its bed and receding further south of its present bed, in the course of its withdrawal, many of the meanders of the old courses were converted into oxbow lakes. It is along the edges of such lakes, rich in aquatic fauna and marked by wild grasses including those with edible grains, that the locales of early Stone Age settlements in the valley have been identified (Figure 3). Today, a large number of these lakes have been filled up and converted into farmlands, although their morphology still allows them to be identified as extinct lakes.

There have been major shifts in the configuration of the drainage lines as well. The course of the Ganga itself, for instance, has undergone major alteration, especially marked in the lower section of its valley. Presently, the Ganga meets the sea in two channels: the Bhagirathi-Hoogly in the west and the Padma in the east. The Padma is the major channel of the Ganga, receiving the waters of the Brahmaputra and the Meghna rivers which carry between themselves the entire drainage of the northeast. However, till the twelfth century, the Padma was only a spill channel of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly. Between the 12th and 16th centuries the significance of the two flows was more or less even, but from the sixteenth century onwards, the flow of the Padma became more significant.

Along with climatic and hydrographic shifts, the vegetational history of the Ganga valley has also been a shifting one. Today, forests and woodlands have practically disappeared but till the 1840s, a large part of the area was densely forested. Pollen analysis together with archaeozoological evidence for the presence of wild boar, a number of species of deer,

Figure 3 Mesolithic sites in the middle Ganga plains (after Chakrabarti 2006).

Elephant, rhinoceros, and water buffalo in the middle Ganga valley suggest an environment made up of forests, grasslands, and marshes. The magnitude of the ecological shift can be gauged in relation to the Rhinoceros unicornis, which lives in open country, well adapted to a swampy habitat. This animal was present at archaeological sites in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, underlining the existence of a conducive climate and vegetation cover. Changes in the forest cover extend into the deltaic region. The immense estuarine Sunderbans forest, named after the Sundari (Heritiera formes) plant which is endemic in the region, has a shifting history. Palynological investigations of a series of profiles have shown that a forest resembling the current mangroves of the Sunderbans extended up to Calcutta about 2640 and 7030 years ago. The general picture of the area in and around Calcutta is that of a landscape frequently transgressed by sea water but also getting fresh water from rivers.

Finally, a general point about the minerally poor character of the Ganga valley needs to be addressed. Geographers and historians have frequently emphasized this as a permanent disability of this large stretch of alluvium. What has not been sufficiently highlighted is that this lack of resources is compensated by the presence of resource-rich highlands towards the north and the south. The Chhotanagpur plateau, for instance, provides a kind of backdrop, from the Gaya region till the western section of the Bengal delta. This mineral-rich plateau has always been the most important source of raw materials to the protohistoric and historic Gangetic segments that are adjacent to it. Similarly, a large area of the middle Ganga valley is marked by the presence of the Kaimurs and the Sonabhadra plateau on its south. The interaction of the stone-devoid riverine plain with the southern plateau goes back to the Early Holocene when Mesolithic settlements using microliths and other stone objects become sharply visible. Again, the use of iron in the Lucknow region of the upper Ganga valley in the early second millennium BC has to be understood in relation to the rich iron ore-bearing area at the fringe of Banaras. There seems to have been a distributive network in place which articulated the supply of smelted bloomery iron from the southern hill fringe to a section of the Ganga plains. So, even though the Gangetic alluvium lacks stone and metal ore, it could and did easily access resources from the hilly outliers that fringed it.

World History

World History