Earlier models for the origin of the Indus civilization proposed that it was the result of direct or indirect influence from urban societies in Mesopotamia or Iran to the west. Over the past several decades, new excavations and better radiocarbon dating have resulted in more complex models for interpreting the origins and transformations of this early urban society. The Indus region was clearly not isolated from the events going on in other parts of West Asia; nevertheless, the origin of Indus cities such as Harappa and Mohenjo-daro can be traced to indigenous socioeconomic and political processes. Continued archaeological excavations in both India and Pakistan have revealed the presence of numerous different types of sites that provide a more complete understanding of the origins and decline of the Indus civilization.

While most scholars look to the Early Neolithic as the foundation of later urban centers, it is important to include a discussion of hunting and foraging communities who have continued to coexist and interact with settled communities throughout human history. With the retreat of glaciers in the northern subcontinent around 12 000-10 000 years ago and changes in climate, major changes in the species and distributions of fauna and flora in the South Asian subcontinent resulted in the establishment of new strategies of

Oxus (Amu Darya)

Bactro-Margiana

Tradition

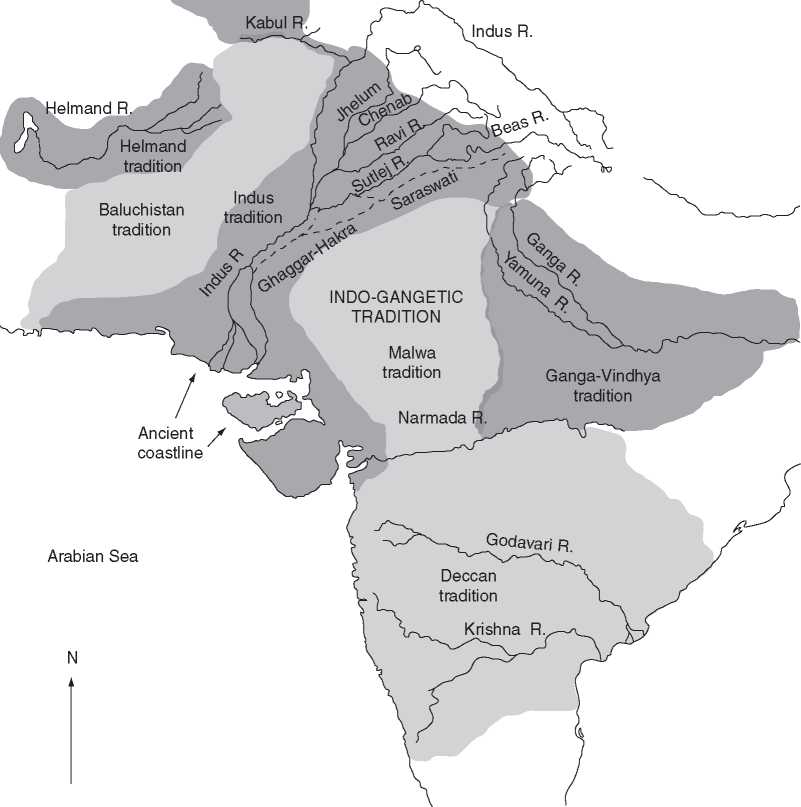

Figure 1 Major traditions in South Asia.

Tablet Indus Tradition

Foraging era 10 000-2000 BCE

Mesolithic and Microlithic

Early Food Producing era 7000-5500 BCE

Mehrgarh Phase

Regionalization era 5500-2600 BCE

Early Harappa phases

Ravi, Hakra, Sheri Khan Tarakai,

Balakot, Amri, Kot Diji, Sothi

Integration era

Harappan phase 2600-1900 BCE

Subdivided at the site of Harappa into Period 3A - 2600-2450 BC Period 3B - 2450-2200 BC Period 3C - 2200-1900 BC

Localization era

Late Harappan phases 1900-1300 BCE

Punjab, Jhukar, Rangpur

Foraging and hunting. The ‘Foraging era’ represents a relatively long period of time and broad geographical area where mobile and semisedentary foraging and hunting communities began focusing on intensive exploitation of specific plants and animals. In parts of Afghanistan and the edges of the Indus valley these adaptive strategies eventually contributed to the domestication of humped zebu cattle and possibly other species of animals and plants.

During the Neolithic or ‘Early Food Producing era’, which dates to around 7000-5500 BCE at sites such as Mehrgarh, Pakistan, there is evidence for the emergence of wheat and barley agriculture and the herding of domestic cattle, along with sheep and goat. These plants and animals became the primary subsistence base for the development of larger towns and eventually cities in the Indus region. Major trade networks were also established during this period, connecting small agro-pastoral communities with distant resource areas. These networks extended from the Arabian Sea along the Makran coast to the highlands of northern Afghanistan, and from the Baluchistan hills to the deserts of Sindh and Rajasthan.

In the subsequent Chalcolithic or ‘Regionalization era’, 5500-2600 BCE, distinctive regional cultures became established in the northern and southern alluvial plain, as well as in surrounding regions. Small villages became established in agriculturally rich areas and larger villages grew up along the major trade routes linking each geographical region and resource area. Some settlements, such as Mehrgarh, which is situated at the base of the Bolan Pass, became important craft production and trade centers. At Mehrgarh a wide suite of specialized crafts were developed for local use as well as for regional trade: pottery making, stone bead making, shell ornament production, copper working, and eventually bronze working, as well as glazed steatite and faience bead making. Distinctive pottery styles and painted designs, along with regional human and animal figurine styles can be seen in other regions at sites such as Rehman Dheri (Gomal Plain), Sheri Khan Tarakai and Tarakai Qila (Bannu Basin), Sarai Khola (Taxila Valley), Harappa and Jalilpur (central Punjab), Siswal (Haryana), Kot Diji (Sindh), Amri and Ghazi Shah (southern Sindh), Nal/Sohr Damb (southern Baluchistan), and Balakot (Makran coast). Different regional cultures of phases have been named after the regions or sites where they were first discovered, such as Hakra, Ravi, Sothi, Amri, and Kot Diji phases. These cultures are collectively referred to as Early Harappan, because they set the foundation for the development of major urban centers in the core agricultural regions and at important crossroads.

In addition to the developments in the core areas of the Indus and Saraswati-Ghaggar-Hakra valleys, recent excavations in Gujarat, India reveal the establishment of Early Harappan cultural traditions in Kutch and Saurashtra. The sites of Dholavira, Loteshwar, and Nagwada appear to have links to Amri and Kot Diji phase cultures in Sindh, but also reflect a local tradition from Gujarat, sometimes referred to as the Anarta culture. Many of the raw materials traded during the Early Harappan period derive from Gujarat, but the degree to which local cultures in Gujarat contributed to the Early Harappan and subsequent Harappan cultural traditions is still under investigation.

At the end of the Regionalization era, during the ‘Kot Diji phase’, the first urban centers began to emerge in the Indus and Saraswati-Ghaggar-Hakra plain. At the site of Harappa, which is the best-documented settlement, the early urban phase dates from around 2800 to 2600 BCE (Figure 2). This settlement grew to more than 25 ha in area and was divided into two walled sectors. Smaller villages dating to the same time period have been discovered in the hinterland around Harappa and reveal that the site was a central place in an urban network and also had links to distant resource areas.

At Harappa there is evidence for the first use of the ‘Early Indus script’, standardized weights, writing, and square stamp seals that were used to stamp clay sealings on bundles of goods or store rooms. Other small and large sites dating to this period reveal local developments in artifact styles, stamp seal styles, graffiti on pottery, and settlement planning. Standardized mud bricks used for building city walls and domestic architecture also appear at this time. The use of cardinal directions for orienting streets and buildings, and the use of bullock carts for transport of heavy commodities into the settlement begins during the Kot Diji phase at Harappa and numerous other sites

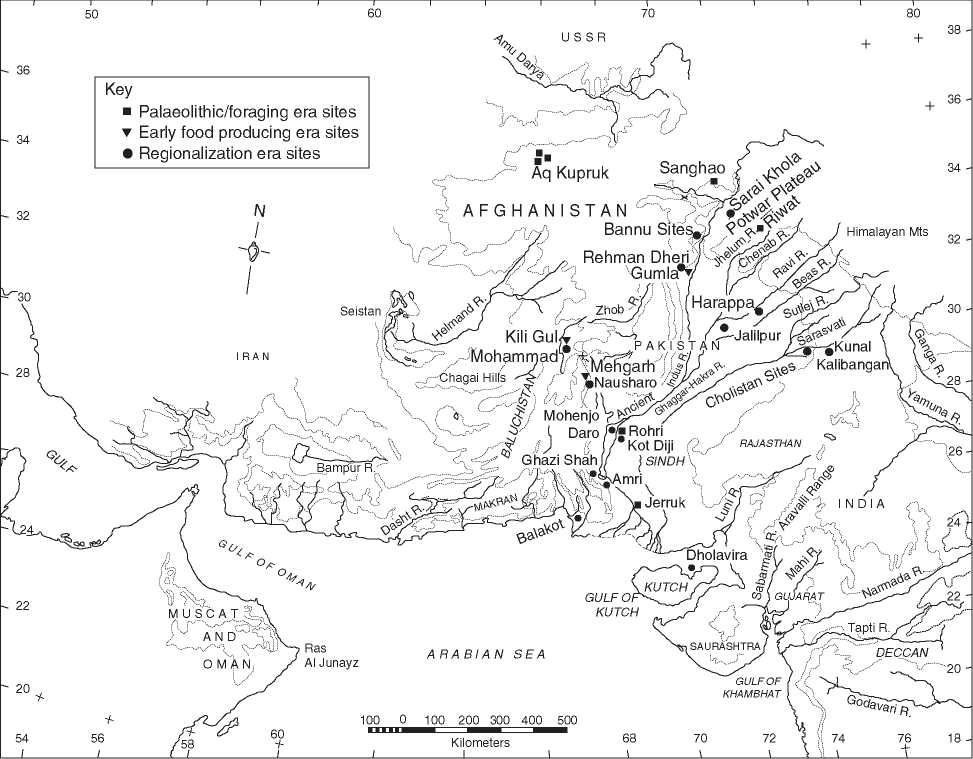

Figure 2 Major geographical regions and prehistoric sites.

Throughout the greater Indus region. Together these developments confirm the emergence of hierarchical social, economic, and political systems associated with early urbanism.

Kot Diji phase sites have been found in the Gomal plain (Rehman Dheri), Kacchi plain (Nausharo), Taxila valley (Sarai Khola), along the bed of the Ghaggar-Hakra river (Jaliwali, Gamanwala, etc.), in the southern Indus region (Mohenjo-daro, Kot Diji, and Ghazi Shah), as well as in Kutch (Dholavira). The precise nature of regional interaction and chronology of local cultural developments is still unclear, but taken as a whole, these sites set the stage for the rise of large urban centers that came to dominate the greater Indus valley region.

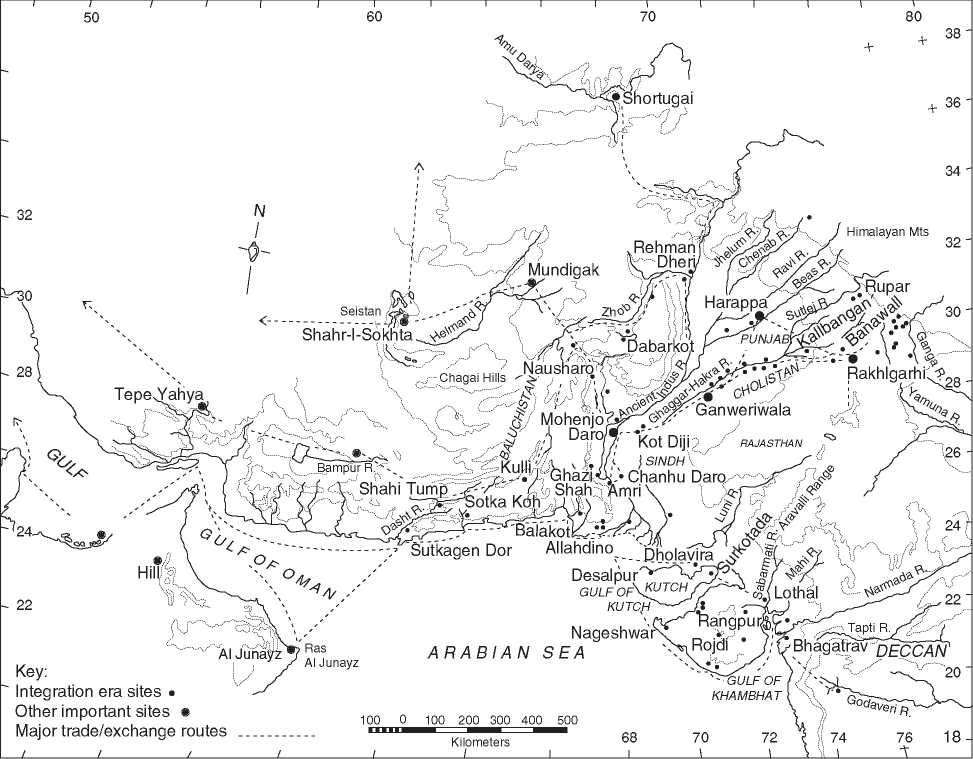

The Integration era, Harappa phase, dates from around 2600 to 1900 BCE, and it is during this long time span that cities such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Rakhigarhi, Dholavira, and Ganweriwala grew to their largest extent (Figure 3). This 700-year period can now be divided into three subphases on the basis of changes in pottery, use of seals, and architecture as seen at the site of Harappa and other major settlements. Although the precise dates may differ from one site to another, at Harappa, these subphases are referred to as period 3A (2600-2450 BCE), 3B (2450-2200BCE), and 3C (2200-1900BCE). Some scholars still refer to this long time span as the ‘mature’ Harappan period (or Mature Harappan), but excavations and radiocarbon dating at the site of Harappa indicate that the artifact types generally associated with the so-called ‘mature’ Harappan period actually only occur during the last half of this 700-year time span.

During the Harappa phase, the largest urban centers may have directly controlled their surrounding hinterland, but there is no evidence for hereditary monarchies or the establishment of centralized territorial states that controlled the entire Indus region. Cities, such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, and Dholavira were clearly being ruled by influential elites, probably a combination of merchants, landowners, and religious

Figure 3 Integration era, Harappa phase sites.

Leaders. Smaller towns and villages may have been run by corporate groups such as town councils or individual charismatic leaders, but there is a conspicuous absence of central temples, palaces and elaborate elite burials that are characteristic of elites in other early urban societies in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China. Hierarchical social order and stratified society is reflected in architecture and settlement patterns, as well as artifact styles and the organization of technological production. A vast network of internal trade and exchange and a shared ideology united the greater Indus valley. There was widespread use of similar styles of pottery, figurines, ornaments, the distinctive Indus script, seals, and standardized weights. Massive mud-brick walls surrounded most large settlements, and appear to have functioned primarily for control of trade access into the cities. These walls also would have served as formidable defenses, but there is no evidence for major conflict or warfare at any major center. A more detailed discussion of the Harappa phase will be presented below.

During the ‘Localization era’, ‘Late Harappan phases’, from 1900 to 1300 BCE or even as late at 1000 BCE, the major cities and their supporting settlements began to lose power due a number of factors. Shifting river patterns and the eventual drying up of the Saraswati-Ghaggar-Hakra River resulted in the abandonment of many sites and migration into the Indus valley, Gujarat or to the Ganga-Yamuna valley. The disruption of agriculture and the eventual breakdown of trade and political networks led to the decline of urbanism and the disappearance of many distinctive features of the Indus culture. The Indus script and inscribed seals were no longer used, and writing disappeared along with the use of cubical stone weights and many forms of symbolic objects. Other social and religious factors also contributed to the gradual reorganization of trade and technology and the emergence of new cultural, political and religious traditions.

Although changes in material culture and socioritual traditions are well documented, there are also significant continuities. Even though cubical stone weights disappeared, the weight system used during the Early Harappan and Harappan periods continued in use in later periods and is still used in South Asia today. Other continuities are seen in pottery styles and technology, some symbolic objects, overall site layout, the use of standardized bricks, etc. These continuities justify the use of the term Late Harappan to characterize many of these traditions. The Punjab phase, Cemetery H culture spread throughout the Punjab and Ganga-Yamuna region, the Jhukar phase and related cultures were found in Sindh and Baluchistan, and the Rangpur phase includes the Lustrous Red Ware and associated Black-and-Red ware cultures that were present in Gujarat, Rajasthan, and the Malwa Plateau.

In the northern Indus valley and parts of Baluchistan some sites show an overlap between Late Harappan and Bactro-Margiana material culture. In the Gangetic region there is overlap with the Copper Hoards culture, the Ochre Colored Pottery, and Painted Gray Ware culture. Some of these cultures may be associated with Indo-Aryan speaking Vedic communities mentioned in the sacred hymns of the Rig Veda and later Brahmanical texts, but there is little consensus among scholars on this point. Considerable research still remains to be done on this transitional period, but some answers should be forthcoming from the many new sites that have been discovered in northern Pakistan and India.

World History

World History