The geography of early Buddhist archaeological sites is in general associated with rivers, ancient coastlines, and trade routes by land and water. There is also a more nuanced geography, economic, political, and religious aspects of which will be discussed in the following sections. A fundamental feature of its economic geography will, however, be mentioned immediately: Buddhism has always been associated with societies which, through agricultural intensification or through trade, possessed enough surplus food to be able to support the variable, but sometimes considerable numbers of men who formed its monastic communities. Buddhist monks were required by their disciplinary rules (the vinaya) to refrain from providing for their own food and other material needs, and instead to offer the laity the opportunity of making merit by supporting them.

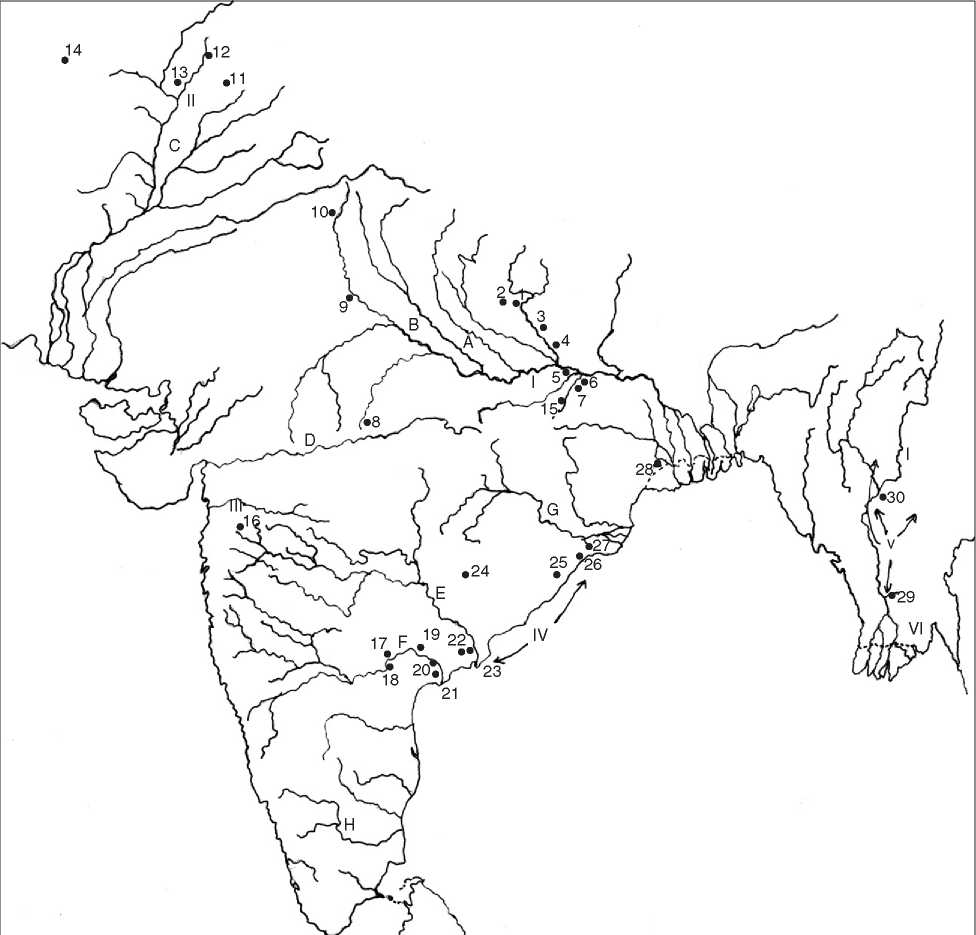

Originating in Northeast India, the geography of the spread of early Buddhism was particularly associated with sites belonging to the developed Iron Age, undergoing urbanization and the crystallization of states in the Ganges-Yamuna and Indus Valleys, and along the valleys of the Mahanadi, Godavari, and Krishna Rivers and their tributaries which drained a central area of peninsular India from the northwestern Deccan, all the way to the coast of Southeast India. Thus the geography of Buddhism in the five centuries following the Buddha’s death (his nirvana), encompassed a wide spatial extent but was very uneven in its intensity (Figure 1).

The life of the historical Buddha - also known as the Sakyamuni, sage of the Sakya people - provides some of the earliest dates in Indian history. Towards the end of the twentieth century there were controversies and downward revisions of these dates which have major implications for Indian historical archaeology and ancient history as a whole and in particular for the apparent discontinuities in early Buddhist archaeological evidence. A combination of archaeological and cross-textual evidence does indeed suggest that the Buddha’s birth and death took place approximately 100 years later than previously supposed, that is, that he was born in the first half of the fifth century BCE and died eighty years later between c. 400 and c. 380 BCE. The importance of these revised dates will become evident when we consider below the typology and chronology of early Buddhist monuments in India.

This article will not consider Buddhist thought, but will focus on those aspects reflected in the material remains of Buddhist sites. Aspects of Buddhist thought have antecedents in earlier, Upanisadic traditions. They concern concepts of central importance to the three great Indic religions: Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism. Two of these are, karma (which loosely equates to destiny) and samsara (the chain of birth and rebirth). Karma is not conceived as an indifferent, impersonal fate but rather as an individual fabric woven out of the accumulated actions (especially merit-making) of a being over many past existences - samsara - which will determine the level and fortunes of that individual’s future incarnations. The desire of all sincere Buddhists, Jains, and Hindus is to be released from the chain of existences and to become united with the Universal force. The many differences among and sectarian divides within these three Indian religions concern how that release may be achieved, as an individual or as a group, and how both the agents of release and what one is released into are conceptualized: in the form of many gods or god-like beings and multiple heavens, as a void or as a universal force. Of these three great Indian religions, only Buddhism has become a powerful, enduring influence outside India. Hinduism was adopted in parts of Southeast Asia for a limited period in the late first millennium CE, only to be merged with Buddhism (in Bali, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos) or Islam (in most of Indonesia and Malaysia). Buddhism is said to be the fastest growing religion in the West today and is enjoying some resurgence in China.

The historical Buddha was contemporary with Mahavira, the founder of Jainism. Thus the revisions of the chronology of the Buddha’s life and death affect Jainism equally. Both lived and taught in the Ganges Valley during the fifth to fourth century BCE, in the area that became the state of Magadha in the fourth century BCE (mainly present-day Bihar), whereas the collection of Indic beliefs and practices known as Hinduism crystallized some centuries later and is still evolving. Buddhism became distinctive for its focus on the three jewels (triratna) of its teaching: the Buddha, dhamma (rules for righteous living), and sangha (the monastic community). All three elements played a central part in the strength of Buddhism in South Asia, c. fourth century BCE to twelfth century CE, and are the foundations of Buddhism’s continued appeal to large populations outside India in the world

Figure 1 Early Buddhist sites of India and Burma.

Today. It has often been argued that, by the time of Buddhism’s eclipse in India, such long processes of reciprocal assimilation between Hinduism and Buddhism had taken place that it was possible for Buddhists to become Hindus without abandoning key concepts and practices of their religion. One must also consider however that, in the face of the Muslim invasions of the sub-continent from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries onwards, religious identities on both the Islamic and anti-Islamic sides hardened in the process and the pressures on Buddhists to support the Hindu and Sikh kings leading the resistance to Islam probably became irresistible. Throughout its history, Buddhism has been equally dependant on the patronage of rulers and the loyal adherence of the lower classes of every society it has touched.

World History

World History