Army had failed in 1862 to get a foothold in the North. But it was June 1863 now, and Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was at its fighting peak.

High Hopes. The men were deadly in battle now, and their commander had firm hopes that they could defeat the Army of the Potomac on Union soil. Lee was still holding onto the hope that France and Britain could be convinced to come to the aid of the Confederacy.

Behind the mountain screen of the Blue Ridge, Lee’s men marched down the Shenandoah Valley and crossed into Maryland. Now that he was across the Potomac River, the fingers of Lee's three corps could reach out and threaten Hamsburg and Baltimore.

Lee’s cavalry' commander, Jeb Stuart, was instructed to keep an eye on Hooker and his Yankees and warn Lee if they started moving north. However, Stuart lost track of the Union army and let Lee advance blindly.

The Army of the Potomac was marching quickly to intercept Lee, but he didn’t know it. He was shocked when he found out that the Yankees were already in northern Maryland and coming on fast.

The First Day. Lee ordered his scattered army to concentrate at Cashtown near the crossroads of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. Early on July 1, a Rebel brigade, hunting for desperately needed shoes, blundered into two Yankee cavalry brigades holding the town. The chance meeting was about to turn into the fiercest battle of the entire war.

In charge of the Yankees was General John Buford. He wasn’t about to let go of this comer of high ground. He ordered his men to get off their horses and fight the Rebels on foot. This they did all morning, stubbornly holding off the Southerners until help arrived.

By midaftemoon Lee brought up reinforcements and had broken the Union lines west and north of the city. Blue infantrymen streamed back through the streets of the town. Hundreds were captured, trapped in alleys and yards. But most rallied on Cemetery Hill, a strong defensive spot.

During the night, Lee tried to get General Richard Ewell to attack and seize Cemetery Hill. But Ewell failed to act. His caution allowed Union reinforcements to set up a strong line along the ridges during the night.

The Second Day. Union General George Meade, Hooker’s replacement, had formed a fishhook line of men southeast of Gettysburg. These 60,000 men were anchoi'ed at Culp’s Hill. The curve of the hook was at Cemetery Hill, with the shaft mnning down Cemetery Ridge (see map on page 55).

Lee’s right flank commander. General James Longstreet, looked at the situation and advised Lee to leave the Yankees on the ridge alone. An assault on those strong positions might well be a disaster. Longstreet suggested that Lee move the men south and let the Yankees come after them. But Lee overruled him. "No," he said. “I am going to whip them [here], or they are going to whip me."

Cemetery Ridge. Lee aimed Longstreet’s men at the Yankees’ left flank. Ewell was ordered to charge the far right. Lee hoped to crorsh the Union line in a pincer movement.

At 4 R. M., sweltering in the July heat, Longstreet's divisions surged to attack in the face of heavy fire. The men smashed headlong into a stray Union corps and

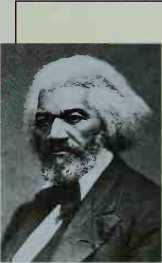

Frederick Douglass began life as a Maryland slave and ended it as the country’s greatest black leader. Taught to read and write by his owner’s wife, Douglass escaped to freedom in the North at the age of twenty-one. In 1841, he joined the Massachusetts AntiSlavery Society and became one of its most effective speakers. Six years later he founded his own newspaper. The North Star, to spread his abolitionist arguments. Once war broke out, he insisted repeatedly that it was about slavery. ‘This war,” he said, “disguise it as they may, is [about] perpetual slavery against universal freedom.”

Once Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation,

Douglass campaigned loudly for the right of free blacks to fight for the cause of the Union and freedom. “The arm of the slave [is] the best defense against the arm of the slaveholder. Who would be free themselves,” said Douglass, “must strike the blow...I urge you to...smite to death the power that would bury the Government and your liberty in the same hopeless grave."

Perhaps Frederick Douglass’ greatest insight was that blacks—whether former slaves or freemen—were not a separate society.

“We are Americans,” he reminded the country during the war, “and shall rise and fall with Americans.”

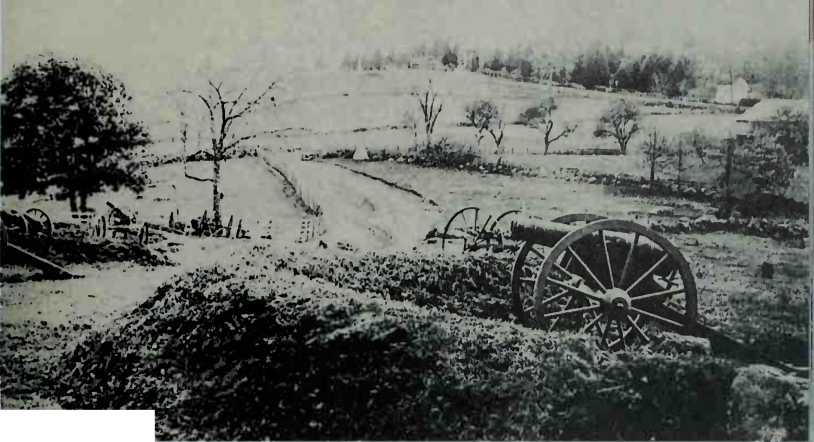

Sunlight filters over the fields at Gettysburg. This battle, the bloodiest of the war, claimed over 51,000 American casualties.

Shattered it, capturing a boulder-topped ridge known as Devils Den.

The fighting there and in the wheat field was a whirl of confusion and carnage. One New York officer looked down onto the battle and was horrified: “The wild cries of charging lines, the rattle of musketry, the booming of artilleiy and shrieks of the wounded [created] a scene like very hell itself.”

“The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. ”

—Abraham Li7tcoln, Gettysburg Address

Little Round Top. Overrunning Devil's Den, the Rebels

Surged up two rocky hills. Big and Little Round Top. Rebel cannons sitting on top of Little Round Top would be able to blast the whole Union line. It was the key to the day’s battle.

But a Union general saw what was happening. In the nick of time he rushed a brigade onto Little Round Top. The 20th Maine Regiment found itself alone at the far end of the Union line. Crouching down among the boulders.

They threw back five separate charges by the 15th Alabama. Colonel Joshua Chamberlain remembered the tangled fighting like the landscape of a nightmare: "At times I saw around me more of the enemy than my own men.”

Chamberlain and his men bravely held on—Little Round Top was saved. Lee’s two flank attacks had almost succeeded. The Rebels had broken the Union line on Cemeterv’ Ridge and Cemetery Hill. Neither charge, though, had forced the Yankees off the hills for good. Meade’s araiy had been terribly mauled. But he and his generals decided to stay and fight it out.

The Third Day. Lee guessed that Meade had used men from the center of his line to plaster the holes the Rebels had punched in his flanks. On July 3, the Confederate genei'al decided to smash that center: He planned an infantry' assault, helped by massive artillery fire. A fresh division, led by General George Pickett, would lead the charge.

General Longstreet, once again, cautioned Lee against attacking this way. The men, he explained, would have to cross a mile of open ground. They would be under fire the whole way. "General,” Longstreet pleaded, "I have been a soldier all my life.... It is my opinion that no 15,000 men ever arrayed for battle can take that [Union] position.”

But Lee had reached his own crossroads. There was no tur-ning back now. "The enemy is there,” he said, "and I am going to strike him.”

World History

World History