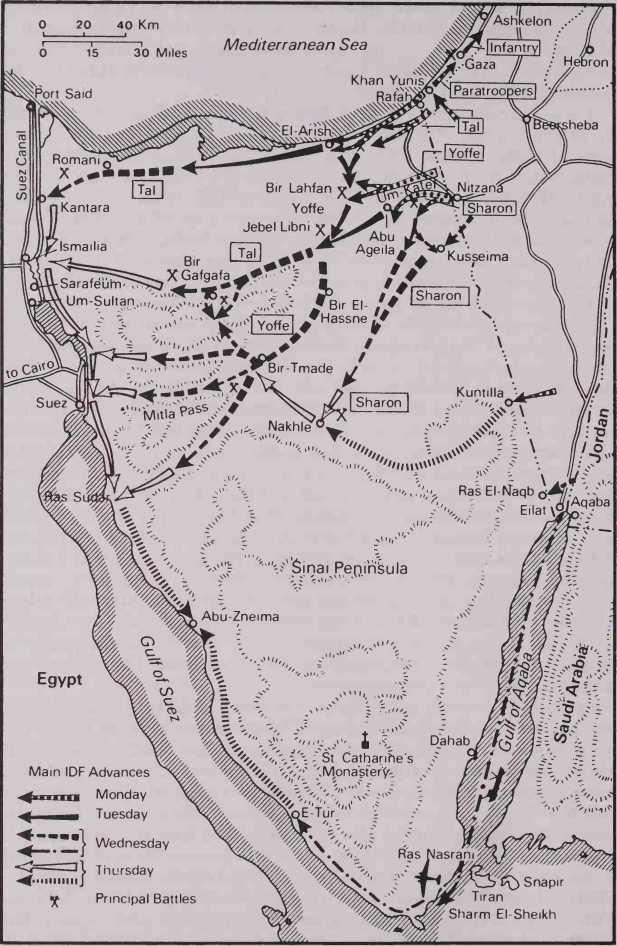

The theatre of war in the Sinai was essentially unchanged since the last war — the northern sandy area with the main coastal route and the railway; the central hilly and valley area criss-crossed by roads and tracks; and the southern mountainous area. But, since the 1956 Campaign, the Egyptians had invested considerable funds and energy in restoring the roads and fortifications destroyed in that campaign, and in transforming all of the north-west Sinai into one large fortified area, designed to provide a firm base for an attack on Israel. Additional roads had been constructed following the lessons learned from the 1956 Campaign. A mountain pass, the Gidi (which runs parallel to the Mitla Pass), had been cut through the range of mountains that run parallel to the Suez Canal in order to ensure additional flexibility in movement of forces. Additional roads running from north to south had been added to connect the main trans-Sinai arteries. Giant strongpoints had been established, including air bases, training camps, storage depots — all combining to form one solid fortified framework, stretching back from the border with Israel deep into the heart of the central Sinai. The Gaza Strip had been converted into a fortress, with dug-in tanks and artillery covering all approaches. The Egyptian forces pouring into the Sinai at the end of May and beginning of June 1967 entered bases well prepared in advance, fully equipped and supplied. In a matter of days, the entire force was ready to move into battle from these previously-prepared positions.

The Egyptian forces in the Sinai were five infantry and two armoured divisions, totalling some 100,000 soldiers equipped with over 1,000 tanks and hundreds of artillery pieces. The infantry was deployed forward along the main axes, close to the border with Israel, while the armoured formations were to the rear, primarily in the central Sinai and covering also the southern flank of the front. The northern axis was defended by the Palestine 20th Division commanded by Major-General Mohammed Hasni, which was deployed in the Gaza Strip, and the 7th Infantry Division under Major-General Abd el Aziz Soliman, which was responsible for the area south-west of the Strip, from Rafah to El-Arish. To the south, along the central axis, the 2nd Infantry Division, led by Major-General Sadi Naguib, was deployed in a vast fortified locality covering the area stretching from Kusseima to Abu Ageila, and including the Um-Katef stronghold (an area that had figured prominently in the Sinai Campaign of 1956). The 3rd Infantry Division, under Major-General Osman Nasser, was west of the northern and central divisions in the Jebel Libni/Bir El-Hassne area, providing the necessary depth in

Deployment. To the south, the 6th Mechanized Division, commanded by Major-General Abd el Kader Hassan, was in position along the Kuntilla-Themed-Nakhle axis — the same axis along which the opening breakthrough of the 1956 Campaign had been undertaken by the paratroop brigade under Colonel ‘Arik’ Sharon.

The two armoured fists of the Egyptian Army in the Sinai were deployed in strategic depth. The crack 4th Armoured Division, led by Major-General Sidki el Ghoul, was concentrated in Wadi Mleiz between Bir Gafgafa and Bir El-Tamade, a central air and logistics base deep in the Sinai. The second division-sized armoured task force. Force Shazli, named after its commander, Major-General Saad el Din Shazli, was moved forward close to the Israeli border, between Kusseima and Kuntilla, and held in readiness to break into Israel and cut off the southern Negev area and the southern port of Eilat from the remainder of Israel.

The Israeli Southern Command, under Major-General Yeshayahu Gavish, consisted of three divisions commanded respectively by Major-Generals Israel Tal, Avraham Yoffe and Ariel ‘Arik’ Sharon. General Gavish, a graduate of L’Ecole de Guerre in Paris, and whose limp came from a wound received in the War of Independence, was a highly articulate and brilliant officer. Indeed, he was considered to have been one of the more outstanding officers in the Israeli Command. In the 1956 Sinai Campaign, he was Chief of the Operations Division in the General Staff and, as such, had been the liaison between the then Chief of Staff, General Dayan, who insisted on being forward with his troops during the fighting, and the General Staff. After the Six Day War, Gavish was to be very much in the running to become Chief of Staff after General Bar-Lev’s tour of duty, and was favoured by General Moshe Dayan over General Elazar. However, Dayan, although Minister of Defence, was unable to assert himself in the face of the combined preference of Golda Meir, the Prime Minister, and General Bar-Lev, the retiring Chief of Staff, for General Elazar. As a result. General Gavish retired from the armed forces to become Deputy Director-General of the Koor Industrial Group, the largest industrial group in the country.

General Tal, a small, squat soldier, had served in the British Army in the ranks of the Jewish Brigade Group. A strict disciplinarian, he rose in the ranks of the Israel Defence Forces ultimately to command the Armoured Corps. A graduate in philosophy from the Hebrew University, he soon came to be regarded in the Israel Defence Forces as something of a technical genius: he was twice awarded the coveted Israel Prize for important inventions in the field of security, and later was to design the Israeli main battle tank, the Merkeva (Chariot), one of the most advanced tanks in the world. (Its concept was to be based on the lessons learned by the Israeli armoured forces in their various wars, and particularly in the Yom Kippur War.) A certain degree of controversy grew around him following the Yom Kippur War, in which he served as the Deputy Chief of Staff to General Elazar. Later, he became adviser to the Minister of Defence on development and organization, also becoming regarded as an international authority on armoured warfare.

The Strategy of the Sinai Campaign, 5-8 June 1967

The overall strategy of Southern Command was based on a threepronged break-in by means of three principal phases. The first phase was to open the northern and central axes by destroying the fortified Egyptian infrastructure along them and thereby breaking the back of the Egyptian forces in the Sinai; the second phase was to penetrate into the depths of the Sinai; while the third stage was to take the two mountain passes leading to the Suez Canal and thereby cut off the Egyptian Army from recrossing the Canal. (The Egyptians were not expecting a direct frontal assault. Indeed, they anticipated an opening move similar to that of the 1956 Campaign. The Egyptian Commander-in-Chief in the Sinai, General Abd el Mohsen Mortagui, had decided to deploy the special armoured divisional task force. Force Shazli, close to the border between Kusseima and Kuntilla, so that he could counter immediately by striking into Israel.) In the northern sector. General Tal’s Division was to assault the fortified area of Rafah/El-Arish. In the centre. General Sharon would take the Um-Katef/Abu Ageila complex on which the Egyptian defensive deployment hinged. Elements of General Yoffe’s Division would negotiate the sandy, apparently impassable area between the northern and central axes, thus isolating the two main Egyptian defensive locations and preventing lateral passage of reinforcements or any attempt at co-ordination between the two Egyptian divisions, the 7th and the 2nd, under assault.

The northern area of Rafah/El-Arish was a defensive locality surrounded, as in 1956, by deep multiple minefields and heavily-fortified lines, with infantry brigades dug-in behind a complex of anti-tank weapons sited in concrete emplacements along the outer perimeter. To the rear of the positions, in addition to artillery, over 100 tanks were defensively deployed. The general impression created by the Israeli deployment of forces, which in the southern sector were moved to and fro along the border openly and demonstratively, succeeded in misleading the Egyptians as to the probable planned main thrust of the Israeli forces — the impression was given that the attack would be launched to the south. As a result, there was an element of surprise when the opening attack took place along the northern axis in the area of Rafah.

Tal’s breakthrough in the northern sector, which was launched at 08.00 hours on 5 June, was achieved by avoiding the minefields around the fortified locations and by breaking into the Rafah area from the north-east near the town of Khan Yunis. This was carried out by the 7th Armoured Brigade commanded by Colonel Shmuel Gonen at the junction of the Egyptian 20th and 7th Divisions, and Rafah was taken after a fierce tank battle. Parallel with this, a parachute brigade reinforced by a battalion of tanks, led by Colonel ‘Raful’ Eitan (indeed the same Brigade in which he led a battalion in the 1956 Sinai Campaign) made a wide, southerly, flanking sweep around Rafah, which was defended by two brigades heavily reinforced by artillery, turning northwards and advancing on the position from the rear over sand dunes the Egyptians had considered impassable. Taking the Egyptian artillery park by surprise, Eitan’s brigade broke into artillery concentrations and mopped-up position after position. Meanwhile, Gonen’s 7th Armoured Brigade advanced westwards to the

Next Egyptian defensive locality at Sheikh Zuweid, which was manned by an infantry brigade of General Soliman’s 7th Division and a battalion of Russian-built T-34 tanks. While a battalion of Centurion tanks drew the Egyptian fire, a battalion of Patton tanks outflanked the position from the north and the south, and it fell to Gonen’s forces. Before El-Arish, Gonen’s forces came upon the heavily-fortified, solid-concrete defences of El Jiradi — the strongest Egyptian position in the vicinity of El-Arish. The Brigade attacked and overcame these defences, then continued to push towards El-Arish. However, the Egyptian forces, which had dispersed among the sand dunes in the desert, regrouped and counterattacked the position, reoccupying it. While Tal’s advance forces were advancing on El-Arish, his rear units were engaged in a struggle for the El Jiradi positions, which changed hands several times. General Tal thereupon concentrated other available forces, which finally occupied the position after bitter hand-to-hand fighting. By the early morning of 6 June, the road was open as a supply route to the Israeli forces already in El-Arish. These were the advance forces of General Tal’s division, which continued along the northern axis of advance and reached El-Arish during the night of 5/6 June.

The following day, part of Tal’s forces continued their sweep westward along the northern axis, in the direction of Kantara on the Suez Canal, whilst the other part of the division under Colonel Gonen moved south to the El-Arish airfield, which fell after a tank battle, opening the road to Bir Lahfan, thus opening an eastern road south to Abu Ageila and a western road south to Jebel Libni. Colonel Gonen, a tough, rough-spoken officer, invariably wearing tinted or sun glasses, was to emerge from this war with an outstanding reputation. A native of Jerusalem, the son of Orthodox parents, he was a student as a young boy at a strictly Orthodox Theological Seminary in Jerusalem. He received his baptism of fire in the War of Independence at the age of 16 in the siege of Jerusalem. In the Sinai Campaign, he served as a company commander in Ben Ari’s 7th Brigade, which he now commanded. He trained in the United States at the School of Armor at Fort Knox (as, incidentally, did most of the senior Israeli officers in the Armoured Corps) and, in summer 1973, he was to replace General ‘Arik’ Sharon as GOC Southern Command. A few months later, the Yom Kippur War broke out. In his appearances before the Agranat Commission (page 236) and also in his subsequent public appearances, Gonen maintained that he had inherited a Southern Command that had suffered from neglect on the part of his predecessor. General Sharon. Be that as it may, he was to become an unfortunate ‘casualty’ of the Yom Kippur War, bringing the career of a courageous, tough, able and professional soldier to an abrupt end.

To General ‘Arik’ Sharon’s division was entrusted the breakthrough along the central Nitzana-Ismailia axis. This axis was vital: from it radiated the roads leading to El-Arish in the north and to Nakhle in the south. A major fortified complex barred the way, based upon interconnecting fortified positions extending from Um-Katef to Abu Ageila in the west, and Um-Shihan in the south, with an outer perimeter

Close to the Israel border at Tarat Urn-Basis and Urn Torpa. In this locality, the Egyptian 2nd Infantry Division was firmly entrenched.

Sharon’s initial assault on 5 June, with an armoured and mechanized infantry force against Tarat Um-Basis, destroyed the Egyptians’ eastern perimeter positions. Sharon’s forces were now before the main defensive positions of the locality, and he brought forward the divisional artillery units to soften them up by persistent bombardment. An armoured reconnaissance group meanwhile moved along the northern flank, over sandy dunes that (as in other places) the Egyptians had misjudged and considered impassable. After a heavy battle, in which a battalion position armed with anti-tank weaponry was overcome at the third attempt, the group bypassed the fortified locality to its south and reached the road junctions leading from Abu Ageila towards El-Arish in the north and to Jebel Libni to the south-west. There, it dug-in. In a parallel move to the south, Sharon sent an additional reconnaissance unit with tanks, jeeps and mortars to block the road connecting Abu Ageila and Kusseima. The result of these two moves was to sever all Egyptian axes of reinforcement from El-Arish, Kusseima and Jebel Libni — and, of course, all possible lines of retreat from Abu Ageila in any direction.

At dusk on 5 June, the order was given to begin concentrated artillery fire. A paratroop battalion was flown by helicopter into the rear area of the locality in order to neutralize the Egyptian artillery, and then tank units advanced directly from the east, accompanied by infantry who proceeded to clear the enemy trenches and positions. When the infantry reached the road from the north, the tank unit that had blocked that line of Egyptian resupply and retreat now attacked from the rear. Israeli armour and infantry met in the centre of the locality: by 06.00 hours the following morning, after what was probably the most complicated battle in the history of the Arab-Israeli Wars, the central axis from Um-Katef to Abu Ageila was in Israeli hands. Mopping-up operations took a further 24 hours, but the road was now open for units of Major-General Yoffe’s division to cut deeper along the central axis, towards Jebel Libni.

While the two Egyptian divisions were fighting desperately against the forces of Tal on the northern axis and Sharon on the central axis, the third Israeli division, under Yoffe, was achieving what the Egyptians had considered to be an impossible task. Part of the Division advanced with vehicles and equipment across the soft sand dunes between the northern and central axes, covering a distance of 35 miles in nine hours. By the next evening, 6 June, the force had reached the area of the Bir Lahfan junction, connecting the Jebel Libni and Abu Ageila-Kusseima roads to El-Arish. The mission of the force was to prevent any lateral movement by Egyptian forces between the two axes, and to block any reinforcements from the Egyptian concentrations in the Jebel Libni area. Such reinforcements in the form of an Egyptian armoured force, comprising an armoured brigade and a mechanized brigade, did in fact move along the central axis leading from Ismailia towards Jebel Libni in the early evening. It came upon Yoffe’s leading brigade, under Colonel Yiska Shadmi, lying in wait in hull-down positions at the Bir Lahfan crossroads. Battle was joined, and a

Fierce armoured confrontation raged around the junction, terminating in the complete rout of the Egyptian force, and opening the road for the remainder of Yoffe’s division to proceed south-west towards Jebel Libni.

With the outbreak of war, Egyptian propaganda had begun to put out euphoric stories about the impressive victories that had been achieved by the Arab forces. Tel Aviv was reported to be under heavy air attack, the oil refineries in Haifa were declared to be on fire, and numerous alleged victories were reported from the field of battle. The Egyptian public received the news of the first day of the war with enthusiastic joy. On the second day of war, with news already filtering through, past the Egyptian news media that continued to publish stories of continued successes, a more sober tale began to be heard in the streets of Egypt. (The third day of the war was to mark a radical change, with dismay, chagrin and outrage reflected in the reaction of the population.) Field Marshal Amer, the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian forces, about whom there had been many stories concerning his addiction to drugs, lost his nerve, and he began issuing conflicting orders direct to the field commanders in the Sinai. President Nasser continued during the day to receive the fabricated optimistic reports from the front-line and, indeed, in a telephone conversation in the morning hours, encouraged King Hussein to launch his forces along the Jordanian front, advising him that the Egyptians were now well on their way across the Negev and planned to meet the Jordanian forces pushing down from the Hebron Hills.

According to subsequent speeches by Nasser and by revelations in the trials of the various Egyptian commanders that took place after the war. President Nasser was unaware of the calamity that had befallen the Egyptian Air Force in the early hours of the morning until 16.00 hours that afternoon. Later, in order to explain away the stunning defeat the Arab Air Forces had experienced at the hands of the Israeli Air Force, President Nasser and King Hussein fabricated a story in which they alleged that United States air units had participated in the attack on the Egyptian Air Force. This gauche attempt to explain away a defeat that was now staring the Arab leaders in the face was confounded by the Israelis, who monitored the radio-telephone conversation between the two Arab leaders and two days later released it. King Hussein subsequently admitted that the Israeli tape of the conversation was authentic, and withdrew the allegations, which had by now given rise to a wave of anti-American and also anti-British demonstrations throughout the Middle East.

The conflicting orders that Field Marshal Amer issued to units in the Sinai created an atmosphere of panic among many of the senior commanders, who decided in many cases to save their own skins, abandon their formations and flee for safety across the Suez Canal. Many of them were later to be court-martialled and severely punished. Field Marshal Amer himself was to commit suicide when it became clear to him that he too would have to face trial.

As evidence mounted of signs of demoralization at higher command levels of the Egyptian Army, General Gavish met his three divisional commanders, Tal, Yoffe and Sharon, and urged them to develop new and

¦

More rapid pursuit plans so as to cut off the Egyptian forces before they could make good their escape across the Sinai. The second day of fighting, however, was spent in consolidating the previous day’s gains. General Tal’s forces, which had veered southwards through the El-Arish airfield, reached Bir Lahfan en route to Jebel Libni. Bir Lahfan fell after once again apparently impassable sand dunes had been crossed in order to outflank the Egyptian forces. Jebel Libni constituted one of the major Egyptian bases deep in the Sinai, encompassing several fortified army camps and an air base, and straddling a central road junction with connecting north-south and east-west roads. Here and in Bir El-Hassne, some twelve miles to the south. General Mortagui had deployed the Egyptian 3rd Infantry Division supported by tank units. The forces of both General Tal from the north and General Yoffe from the east now attacked this elongated, heavily-fortified concentration. By dusk on 6 June, most of the camps in the Jebel Libni complex had fallen, and Yoffe’s force continued southwards to Bir El-Hassne. Sharon’s forces in the meantime continued to mop-up the Um-Katef area. Thereafter, they turned south towards Nakhle, in order to deal with the Shazli armoured divisional task force between Kusseima and Kuntilla.

Major-General Saad el Din Shazli was a commando officer highly regarded by President Nasser. In 1960, he had commanded a battalion of the Egyptian commandos within the framework of the UN forces in the Congo. The Egyptian battalion did not acquit itself particularly well in this operation, but Colonel Shazli had continued to enjoy considerable popularity and standing, and was later to command Egyptian forces in Yemen. His force in 1967 was given the major offensive task of cutting the Israeli Negev in the south, to the north of Eilat. In the weeks before the outbreak of the war, during the so-called ‘waiting period’, he engaged in flamboyant demonstrations of Egyptian armoured power before the world press, belittling the Israeli forces facing him. He was to participate in the planning of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, as Chief of Staff of the Egyptian Armed Forces. His nerve apparently broke in that war, after the Israeli bridgehead was established across the Suez Canal in Egypt proper, and he quarrelled with President Sadat during a meeting when, according to President Sadat, Shazli in a state of hysteria urged the withdrawal of the Egyptian forces from the east bank of the Suez Canal. President Sadat refused to accept his recommendations, and ultimately relieved him of his command. He was sent into ‘exile’ as Ambassador to Great Britain, and later to Portugal, but subsequently resigned and called for a revolt against President Sadat. After that he was engaged by Colonel Gaddafi of Libya, presumably to rally around him the Egyptian anti-Sadat forces.

By the end of the second day’s fighting, the main Egyptian defences manned by elements of three divisions had been overrun, and Israeli forces were advancing into the depths of the Sinai towards the major armoured concentrations in the centre, which constituted the last major obstacle before the Suez Canal.

Along the northern axis, Tal’s forces moved rapidly on 7 June towards Kantara on the Suez Canal, meeting resistance only at a distance of some

Ten miles west of the Canal, where Egyptian tanks, anti-tank guns and a few aircraft laid an ambush for the advancing columns and put up a spirited fight. The Egyptian armoured force, which had concentrated at Kantara East, launched an attack on the advancing Israeli task force, which had raced along the northern coast from El-Arish under Colonel Israel Granit. His force had been joined by a detachment of the paratroop brigade under the command of Colonel ‘Raful’ Eitan. Rapidly sizing up the situation, the commander of the Israeli task force executed a fire and movement tactic. Part of Granit’s armoured force blocked the main road by fire and engaged the Egyptian armoured forces in a tank battle at extreme ranges, while the paratroopers on half-tracks and jeeps mounting recoilless rifles outflanked the Egyptian forces that were engaging the Israeli fire-base. The Egyptian armoured force was destroyed, and Granit’s task force broke through to Kantara. By the morning of the following day — the fourth day of the war (8 June) — the banks of the Suez Canal had been reached.

Apart from this independent northern advance, the main effort of the combined Israeli forces in the Sinai now shifted towards the destruction of the huge Egyptian armour concentrations that remained in the central Sinai. General Gavish ordered a co-ordinated two-divisional force to deal with these: Tal’s division moved directly westwards towards the major base of Bir Gafgafa, while Yoffe’s division moved south to Bir El-Hassne and Bir El-Tamade. From there, Yoffe advanced westward on a parallel course to that of Tal, towards the Mitla Pass. Sharon’s division, which had meanwhile mopped-up Um-Katef, pushed south towards Nakhle, compelling Force Shazli and the tanks of the 6th Division to move towards the trap that was being laid by Tal and Yoffe at the Mitla Pass — the only route out of the Sinai. The Israeli forces were in fact funnelling the withdrawing Egyptian forces to the Mitla Pass, where Tal and Yoffe’s forces were waiting to destroy them. The move of Sharon’s forces against the Shazli armoured force and the armoured units of the 6th Division forced them to move rapidly in order to avoid an armoured engagement that would have held up their withdrawal.

Tal’s forces overran the Bir El-Hama infantry base and, farther west, the Bir Rud Salim position. Near the main concentration of armour at Bir Gafgafa, the roads connecting Bir Gafgafa to the west and south (possible supply and reinforcement routes) were soon blocked by Tal’s tank battalions. Tal’s forces came upon an Egyptian armoured concentration that was attempting to fight its way out of the Sinai towards Egypt, a small Israeli armoured force attempted to draw the Egyptian armour and cause it to counterattack so that it would fall into a trap laid by outflanking armoured forces. But the Egyptian force refused to react, so the Israelis launched a frontal attack that was successful after a battle lasting some two hours.

Yoffe’s forces had by now completed mopping-up Jebel Libni and were moving south to Bir El-Hassne, thereby blocking the retreat of the Shazali armoured force. Threatened by the dual advance of Yoffe’s and Sharon’s forces, the remaining Egyptian armour retreated towards what it

Considered to be a safe and direct exit towards the Canal, the Mitla Pass. During this retreat, Israeli aircraft strafed the retreating columns without cease, wreaking havoc amongst the Egyptian forces in the narrow confines of the Pass.

Yoffe’s forces moved rapidly to the Mitla Pass seeking to block its entrance and destroy the mass of armour that was expected to attempt to retreat through it. The routes back from the Sinai converging on the Mitla Pass were gradually becoming crowded with the withdrawing Egyptian units of the 3rd Infantry Division, the 6th Infantry Division, Shazli’s divisional task force, and some elements of the 4th Armoured Division. General Ghoul, commander of the Egyptian 4th Division, meanwhile did his best to create some order in the chaos that was developing along the route.

Meanwhile, Colonel Shadmi’s advance units were desperately racing towards the eastern opening of the Mitla Pass in order to lay an ambush there for the converging Egyptian troops and block their passage westwards across the Suez Canal. The Israeli Air Force, which had complete control of the skies, had a field day here, as aircraft strafed and bombed the vast concentration of Egyptian vehicles converging on the Pass. First hundreds and then thousands of burning vehicles were piling up in the area, leaving little or no room for any of the units to manoeuvre. On its way to the Pass, the forward task force of nine tanks under Colonel Shadmi had run out of fuel, and reached its destination with four of the tanks being towed by the others. They dug-in and blocked the approaches, holding out against desperate Egyptian forces trying to force their way through the Pass and, in the process, almost overwhelming Shadmi’s isolated unit. (Shadmi was eventually to be joined by the remainder of Yoffe’s forces, and only one Egyptian tank succeeded in breaking through this trap — all the others were destroyed.)

In the confusion that ensued in the general area of the approaches to the Mitla Pass, as Israeli forces struggled to reach Shadmi’s small unit holding out and blocking the Pass, and Egyptian units equally desperately tried to reach the Pass and break through in order to reach the Suez Canal, an Israeli tank company became entangled with a column of Egyptian tanks. It was by now dark, and it was impossible to distinguish which tanks were Egyptian and which were Israeli. The Israelis realized that they had blundered into the midst of an Egyptian column, but the Egyptians, who were now rushing westwards in a panic-stricken drive, were unaware of the identity of the tanks that had joined them in the dark. The Israeli commander ordered his unit to continue in the column as if nothing untoward were happening along the road for a short distance and then, on a given order, to veer off the road sharply to the right. They were then to switch on their searchlights and shoot at any tank that remained on the road. This they did: in the process, they destroyed a complete Egyptian tank battalion. Meanwhile, Shadmi’s forces fought a battle against heavy odds all through the night, being saved by the ammunition and fuel that they were able to pick up on the battlefield from the abandoned Egyptian tanks.

Sharon’s forces, in the meantime, continued their push southwards towards Nakhle. At one stage, they encountered an entire Egyptian armoured brigade, the 125th Armoured Brigade of the 6th Mechanized Division, abandoned with all its equipment in perfect condition and in place. The troops had fled. Unknown to Sharon, the commander of this brigade. Brigadier Ahmed Abd el Naby, was taken prisoner with a number of his men by units in General Yoffe’s division. When queried about abandoning the tanks intact, he replied that his orders had been to withdraw, but no instructions had been received about destroying the tanks! Outside Nakhle, Sharon’s forces caught up with an infantry brigade and an armoured brigade detached from the Egyptian 6th Division. In the ensuing battle, some 60 tanks, over 100 guns and more than 300 vehicles were destroyed. Sharon’s force regrouped and moved to link up with Yoffe’s division near Bir El-Tamade.

Tal’s forces, en route from Bir Gafgafa westwards towards the Canal, came upon Egyptian armoured reinforcements making their way eastwards from Ismailia bent on launching a counterattack to delay the Israeli advance to the Canal. Tal’s leading tanks were thin-skinned AMX tanks, and they fought a holding battle against what proved to be an Egyptian armoured division with Russian-built T-55 medium tanks. When the Israeli reinforcements arrived, they engaged the Egyptian brigade from long range, approximately 3,000 yards, because of the poor manoevrability in an area of sand dunes. The Egyptian brigade was spread out to a depth of some 4 miles and, after a battle lasting some six hours, it was wiped out. With his leading brigade deployed on a wide front, Tal advanced towards the Suez Canal.

The final day’s fighting saw the completion of the destruction of the Egyptian armoured forces in the Sinai and the final advance to the Canal. Tal’s two forces linked up on the road running along the eastern bank of the Suez Canal, but, as they did so and as the Israeli forces approached the Canal, the Egyptian forces in the area of Ismailia attacked the Israeli forces from across the Canal with heavy artillery concentrations and antitank missile fire. An active exchange of fire over the Canal developed.

Yoffe’s forces on the central axis broke through the Gidi Pass after encountering opposition from some 30 Egyptian tanks that were supported by the remnants of the Egyptian Air Force. Parallel to this move and simultaneously, his forces pushed their way past the impressive concentrations of destroyed tanks and vehicles, through the Mitla Pass towards the Canal. Another unit of Yoffe’s division moved south-west to the Gulf of Suez, at Ras Sudar. Assisted by a parachute drop, the combined forces took the area and immediately advanced southwards along the coast towards Sharm El-Sheikh. This time there had been no dramatic dash from Eilat to Sharm El-Sheikh as by Yoffe’s 9th Infantry Brigade in the 1956 Campaign (which was not dissimilar to his move across the sand dunes on the night of 5/6 June to the Bir Lahfan junction in this war). The naval task force of three Israeli torpedo-boats, which set out by sea from Eilat as part of a concentrated three-prong assault (paratroop, air and naval), discovered on 7 June that Sharm El-Sheikh

Had been deserted and that the Egyptian naval blockade at the Straits of Tiran, which had deterred the naval forces of the western powers from taking action to open the Straits of Tiran, was non-existent. The paratroopers landed at Sharm El-Sheikh airfield and advanced northwards along the Gulf of Suez to meet up with Yoffe’s forces coming south from Ras Sudar.

Meanwhile, a fierce battle was being fought for the Gaza Strip. The battle for this small area, 25 miles long by 8 miles wide and densely inhabited, had been fought and won during the first two days of the fighting, when Tal and Yoffe were planning the assault on Jebel Libni. When the armoured forces broke-in initially opposite Khan Yunis on 5 June and turned south-west toward Rafah, a parachute brigade reinforced by armour moved northwards along the Strip towards the town of Gaza, fighting through the villages and refugee camps, many of whose inhabitants, reinforcing the Palestinian division, were equipped with weapons. Parallel to this action, Gaza was attacked from Israeli territory west of the town, close to the line of Egyptian border posts on the eastern ridges of the Ali Montar. On the evening of the attack, the forces advancing northwards from Khan Yunis had taken Ali Montar ridge from the south, ascending it under heavy fire. In heavy hand-to-hand fighting, the towns of Khan Yunis and Gaza were taken the following day, and control of the Strip was finally achieved by the early hours of the morning of the third day of the War.

The Israelis estimated that Egyptian casualties in the Six Day War totalled some 15,000. The Egyptians put the figure at somewhat less — approximately 10,000. The Israelis captured over 5,000 soldiers and over 500 officers. Approximately 800 Egyptian tanks were taken in the Sinai, of which at least two-thirds were destroyed. In addition, several hundred Russian-made field guns and self-propelled guns were taken, together with more than 10,000 vehicles of various types. Some months later. President Nasser admitted that some 80 per cent of the military equipment in the possession of the Egyptian Army had been lost in the battles in the Sinai. The Israeli losses on this front numbered some 300 killed and over 1,000 wounded.

A United States electronic intelligence ship. Liberty, was stationed at the outset of the war off the coast of Sinai, and was steaming slowly some fourteen miles north-west of El-Arish. The Americans had not notified either of the sides as to the purpose or the mission of the ship, or indeed of the fact that the ship was operating in the area. It will be recalled that when General Tal’s forces broke through along the northern axis in the direction of El-Arish, the Egyptian forces regrouped and retook some of the positions that had been captured by the Israeli forces. A certain atmosphere of confusion was created by this situation. On 8 June, fire was directed at Israeli forces in the general area of El-Arish. Israeli forces reported that they were being shelled, presumably from the sea. The Air Force was alerted, and identified a naval vessel sailing off the coast of Sinai in the general area that had received artillery bombardment. The silhouette of the ship was similar — particularly to a pilot flying at high

Speed in a jet fighter aircraft — to the silhouette of ships in the service of the Egyptian Navy. Without further ado, the Israeli aircraft attacked this strange naval vessel, which had not been identified as friendly, killing 34 members of her crew and wounding 164. The ship managed to limp back to Malta. After a military enquiry, the Israelis expressed regret and offered to pay compensation to the United States Government and to the families of those who had been killed or injured. But attempts to imply that this was a premeditated attack on the part of the Israeli forces do not stand up to examination, especially having regard to the particularly close relationship that existed at that time between the Governments of Israel and the United States, and to the almost tacit agreement expressed in a circuitous way by President Lyndon Johnson to the Israeli Government, that he would ‘understand’ if Israel saw no way out of the impasse but to embark on war. The blame would appear to have been primarily that of the United States authorities, who saw fit to position an intelligencegathering ship off the coast of a friendly nation in time of war without giving any warning whatsoever and without advising of the position of their ship.

World History

World History