During 9 May 1945 there were several further surrenders; the 30,000 German troops on the Channel Islands; the German garrisons on the Aegean islands of Milos, Leros, Kos, Piskopi and Simi; the German garrison on the Baltic island of Bornholm, a part of Denmark; the German troops still holding out in East Prussia and around Danzig; Germans in western and central Czechoslovakia who fought on against the Russians during much of May 9; German troops likewise still fighting in Silesia, where local memorials record the death on May 9 of more than six hundred Soviet soldiers; and the German garrison which had been surrounded at Dunkirk for more than six months, most recently by Czechoslovak troops commanded by Major General Alois Liska, To the surprise of the Czech, British and French officers who accepted the surrender, the German fortress commander, Vice-Admiral Friedrich Frisius, arrived at General Liska’s headquarters with his own surrender document already signed.

In Moscow, May 9 was Victory Day, welcomed by a salvo of a thousand guns. ‘The age-long struggle of the Slav nations for their existence and independence’, Stalin declared in a radio broadcast that evening, ‘has ended in victory. Your courage has defeated the Nazis. The war is over.’

Throughout Europe, former prisoners-of-war were being brought home. On May 8, more than thirteen thousand former British prisoners-of-war were fiown from Europe to Britain; on May 9, when one of the aircraft crashed on its way across the Channel, twenty-five men on their way home were killed.

In the Pacific, the war knew no abatement or relaxation. On Okinawa, on May 9, sixty Japanese soldiers who broke into the American lines were killed in hand-to-hand fighting. Hundreds of Americans died that day in battles to capture Japanese strongpoints; hundreds more were the victims of battle fatigue and could fight no longer. On Luzon, more than a thousand Japanese soldiers barricaded themselves in caves. Attacked by fiame throwers and explosives when they refused to surrender, all of them were killed after a few days. In Indo-China, it was the Japanese who still had the upper hand; at Lang Son, sixty French soldiers and Foreign Legionnaires, who had managed to hold out since the Japanese occupation, were killed when their fort was overrun; the few survivors, put up against a wall, were machine-gunned as they defiantly began to sing the Marseillaise. Afterwards, the Japanese bayoneted any who showed signs of life. Even so, a few survived the massacre. One of them, a Greek legionnaire by the name of Tsakiropoulous, was caught three days later, and decapitated, together with two Frenchmen, the Political Resident at Lang Son, and the

Local commander, General Lemonnier.

In Europe, the first days of Germany’s defeat saw the suicides of many of those who feared the already announced war crimes trial should they be captured, or recognized after capture. On May 10, Konrad Henlein, who had been Governor of Bohemia and Moravia since May 1939, committed suicide in an Allied internment camp. That same day, in a naval hospital at Flensburg, SS General Richard Gluecks was found dead; it is not known whether he committed suicide, or was killed by some group, possibly Jews, who sought to avenge the concentration camp savageries over which he had presided for more than five years.

From Britain, soldiers were now being fiown across the North Sea, to Oslo, to assist in the disarming of the German occupation forces in Norway. In one aeroplane, which crashed near Oslo on May 10, all twenty-four soldiers and airmen on board were killed.

In the Pacific, ofi’ Okinawa, seven American ships had been hit by Japanese suicide aircraft on May 4, and 446 sailors killed. On May 11, a further 396 men were killed on the aircraft carrier Bunker Hill—three times the American death toll in the 1775 battle which the carrier’s name commemorated.

There was still fighting in Europe on May 11, when Soviet troops overran several pockets of German resistance east of Pilsen. Further south, German troops in Slovenia, near Maribor, continued to fight against Tito’s forces. In East Prussia and northern Latvia, several hundred thousand Germans were still refusing to surrender. But it was now no longer military defeat, but possible future retribution, which loomed; in Oslo, on May 11, the former German ruler of Norway, Josef Terboven, committed suicide by blowing himself up with a stick of dynamite.

Every German concentration camp was now in Allied hands, but many thousands of the inmates were too weak or too sick to survive, despite the food and medical care which were now rushed to them. On May 12, at Straubing, in Bavaria, a forty-two-year-old German lawyer, Adolf von Harnier, died of typhoid fever. Denounced in 1939 as an anti-Nazi by a Gestapo informer, von Harnier had been imprisoned since then. Liberation had come a few days too late to save him.

That day, in mid-Atlantic, a German submarine, the u-234, which had left Norway nearly a month earlier to sail to Japan with General Kessler, the newly appointed German Air Attache to Tokyo, on board, surrendered to the Americans. In the North Sea, German motor torpedo boats were making their way from Rotterdam to Felixstowe, likewise to surrender. Peter Scott, the son of the polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott, was one of the British naval officers who went aboard to escort the German craft to the shore. ‘With some difficulty,’ he later recalled, ‘we persuaded the Germans to fall their crew in on deck as they entered harbour, where a great crowd of spectators was assembled on all the piers and jetties. All at once the armed guards filed on board and the Germans were hustled off the boats. It was the end!’

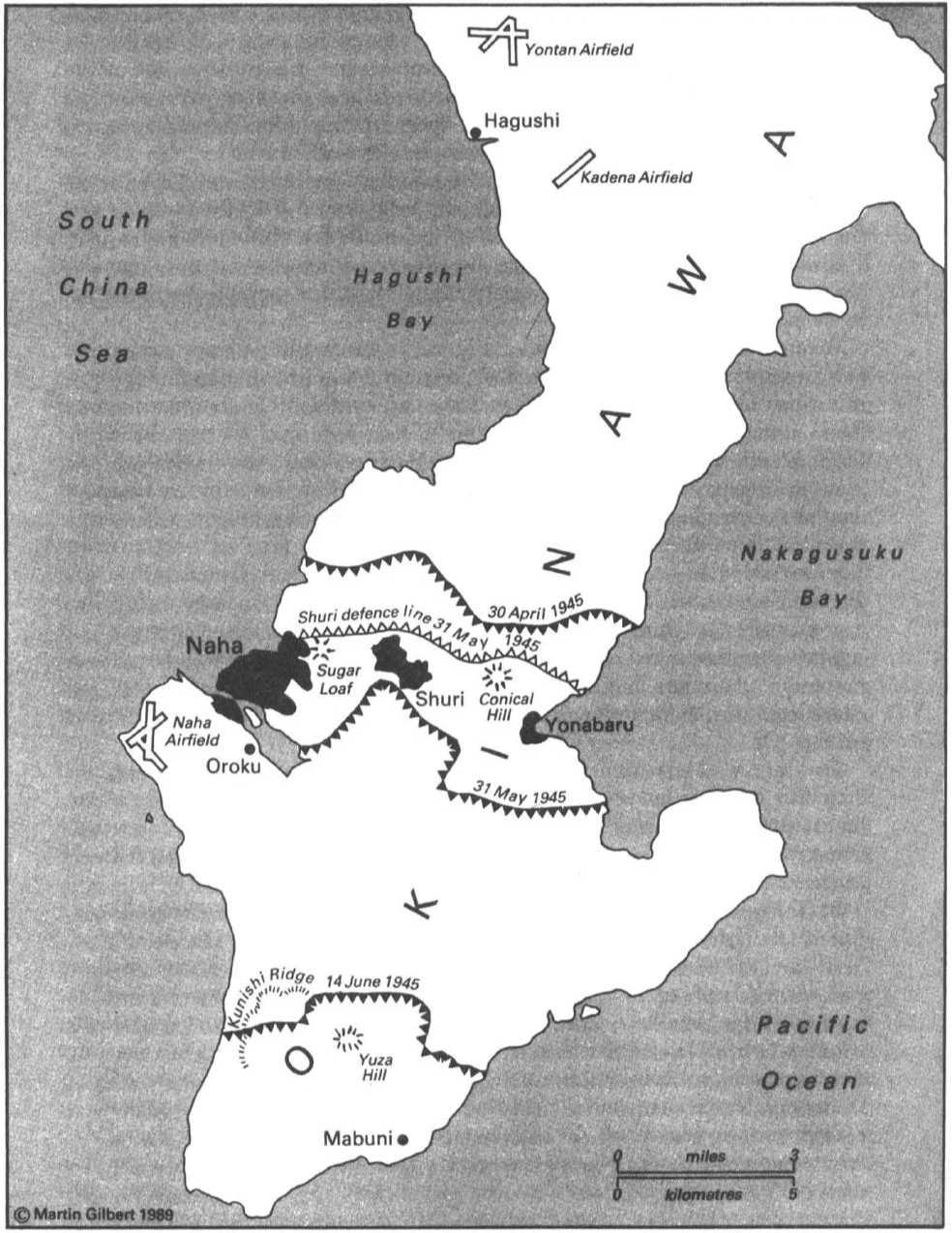

On Okinawa, May 12 saw a renewed American attack against the fortified Shuri line across the southern part of the island. Hundreds died on both sides. ‘Conical Hill’, on Okinawa, fell to the Americans on May 13, nor could the Japanese drive them off again.

On the day after the capture of Conical Hill, American atomic scientists and bombing experts examined possible targets for the atomic bomb. A report discussed by a special top-secret Target committee meeting at Los Alamos that day noted that the hills around Hiroshima, one of the most favoured targets, were ‘likely to produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage’. According to the report, the one drawback was Hiroshima’s rivers, which made the city ‘not a good incendiary target’. Another target under consideration on May 14 was Hirohito’s palace in Tokyo, but this was not one of the four targets which were chosen that day for further study; these were Kyoto—the Japanese holy city—Hiroshima, Yokohama and the Kokura arsenal.

Six days had passed since Germany’s formal surrender to the Allies; on May 14, 150,000 Germans surrendered to the Red Army in East Prussia, and a further 180,000 in northern Latvia. Only one German force, some 150,000 men, the remnants of the German forces in Yugoslavia, was still under arms that day; on May 15 it surrendered to the Russians and Yugoslavs at Slovenski Gradec. For the Yugoslavs, May 15 is Victory Day. In the previous two months’ fighting in Yugoslavia, the Germans had lost 99,907 men killed in action. The Yugoslavs had lost 30,000 men killed during those same final months, a small proportion of the 1,700,000 Yugoslavs who had died since April 1941 in battle, in concentration camps, or in captivity in Germany.

In Burma, the nationalist leader Aung San, who had earlier co-operated with the Japanese, offered his services to the British on May 15. His services were accepted. ‘If the British sucked our blood,’ one of his leading followers told General Slim, ‘the Japanese ground our bones!’. Hence Aung San’s change of side. After Burma’s liberation, Aung San was to be assassinated by political rivals. Two days after Aung San’s change of side, a Canadian member of the British Special Operations Executive, Jean-Paul Archambault, was killed behind the Japanese lines in Burma, when he accidentally detonated one of his explosive charges. Only a year earlier, Archambault had been carrying out similar clandestine duties behind the lines in German-occupied France.

On Okinawa, the ferocity of the fighting reached a climax that day, with the battle for the ‘Sugar Loaf’, a battle which was to last for ten days, and in which nearly three thousand Marines were killed or wounded. Among the dead was Major Henry A. Courtney, who led a charge to the very top of the hill, but was killed after several hours of hand-to-hand fighting on the crest. Courtney was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honour. In a Japanese suicide attack on American positions on May 19, more than five hundred Japanese were killed.

As the battle raged for Sugar Loaf, American Marines were caught up in mortar and grenade battles of exceptional ferocity. When a popular company commander, Bob Fowler, bled to death after being hit, his orderly, ‘who adored him’, as a fellow Marine —William Manchester—later recalled, ‘snatched up a submachine gun and unforgivably massacred a line of unarmed Japanese soldiers who had just surrendered.’ Manchester added: ‘Even worse was the tragic lot of eighty-five student nurses. Terrified, they had

Retreated into a cave. Marines reaching the mouth of the cave heard Japanese voices within. They did not recognize the tones as feminine, and neither did their interpreter, who demanded that those inside emerge at once. When they didn’t, flamethrowers, moving in, killed them all. To this day, Japanese come to mourn at what is now known as the “Cave of the Virgins”.’

On Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines, as well as on Okinawa, the third week of May saw bloody battles, in which even the massive use of flame throwers could not dislodge the Japanese defenders, but could only destroy them yard by yard and cave by cave. Ofl’ Okinawa, on May 24, Japanese suicide pilots sank a fast troop transport and damaged six warships, while ten Japanese pilots, in a daring landing on Yontan airfield, destroyed seven American aircraft and damaged twenty-six more, as well as igniting 70,000 gallons of aircraft fuel, before being killed. Theirs had also been a suicide mission.

In Germany, on May 21, the last of the hundreds of wooden barracks at Belsen was burned down by flame throwers. ‘The swastika and a picture of Hitler were displayed on that last barrack’, Anita Lasker, a survivor of Auschwitz, later recalled, ‘and there was a little ceremony. We all stood there and watched as this last trace of the camp was devoured by the flames’.

On May 22, Hitler’s most senior surviving military Intelligence officer, Reinhard Gehlen, gave himself up to the Americans at Oberursel, north of Darmstadt. In due course, he was to return to Intelligence work against the Russians in postwar West Germany. Also on May 22, an American major, William Bromley, who had earlier been sent to Nordhausen for the express purpose of aiding future rocket research in the United States, began to despatch four hundred tons of German rocket equipment to Antwerp, for shipment across the Atlantic to White Sands, in New Mexico. Requisitioning railway wagons from as far west as Cherbourg, Bromley completed his task before June 1, when —according to the wartime agreement establishing the precise borders of the British, American, French and Russian zones of occupation—the Russians entered Nordhausen.

On May 23, the Russians ordered the arrest of all the Cabinet members of Admiral Donitz’s Government. That same day at Murwik, Admiral von Friedeburg, who just over two weeks earlier had been the signatory of three of the German Army’s instruments of surrender, committed suicide. That evening, Heinrich Himmler, who had been arrested by the British on the previous day, committed suicide by biting a cyanide capsule, while undergoing a medical examination at Luneburg. He had revealed his identity four hours earlier. ‘The bastard’s beat us!’ was one British sergeant’s comment when the deed was done.

On the following day, May 24, Field Marshal von Greim, whom Hitler had made head of the German Air Force in the last days of April, committed suicide in prison in Salzburg.

On May 24, more than four hundred American bombers dropped 3,646 tons of bombs on central Tokyo, and on the industrial areas in the south of the city. More than a thousand Japanese were killed. Also killed in the raid were sixty-two Allied airmen, prisoners-of-war; it was later alleged that they had been deliberately locked into a wooden cell block for the duration of the raid, while all 464 Japanese prisoners and their jailers were taken to a safe shelter.

On the day following this Tokyo raid, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff confirmed November 1 as the date for the start of Operation Olympic, the invasion of the most southerly Japanese island of Kyushu.

On May 26, the Japanese evacuated the Chinese city of Nanning, losing their direct land link with Indo-China. Chinese soldiers quickly reoccupied the city. Two days later, off Okinawa, the Japanese mounted their last major air offensive against American warships, losing a hundred planes without sinking a single ship.

On May 28, at Flensburg, near the German frontier with Denmark, two British officers arrested William Joyce, the broadcaster ‘Lord Haw-Haw’. On him they found not only a German civilian document made out in the name of Wilhelm Hansen, but a German military passport in his real name. He was placed under arrest, and sent back to Britain. Three days later, at Weissensee in Carinthia, a British patrol arrested a man whom they identified as the death camp organizer, Odilo Globocnik; a few minutes after his arrest, he committed suicide by biting a cyanide capsule.

On May 31, those who had to decide on when and where—and if—the atomic bomb was to be dropped on Japan, met in the Pentagon. Speaking for the scientists, Robert Oppenheimer stated, as the official minutes of the meeting record, ‘that the visual effect of an atomic bombing would be tremendous. It would be accompanied by a brilliant luminescence which would rise to a height of 10,000 to 20,000 feet. The neutron effect of the explosion would be dangerous to life for a radius of at least two-thirds of a mile.’ There was a long discussion that day as to what the targets ought to be, and what effect the bomb might have on them. As the meeting came to an end, the Secretary for War, Henry Stimson, ‘expressed the conclusion’, as the minutes noted, ‘on which there was general agreement, that we could not give the Japanese any warning; that we could not concentrate on a civilian area; but that we should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible’. At the suggestion of Dr Conant, Stimson agreed ‘that the most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses’.

It was James Byrnes, the American Secretary of State, who, that same day, took this decision to President Truman, for his approval. Byrnes noted, of their conversation, ‘Mr Truman told me he had been giving serious thought to the subject for many days, having been informed as to the investigation of the committee and the consideration of

Alternative plans, and that with reluctance he had to agree that he could think of no alternative and found himself in accord with what I told him the Committee was going to recommend’.

The alternative plan, to invade Kyushu Island in November, and the far larger Honshu Island in the following spring, had been judged so costly in the lives of the invading force as to make the use of the atomic bomb the preferable plan. If it led to Japan’s surrender before the November invasion, so the argument went, as many as a million American lives might be saved, and the war shortened by as much as a year.

Meanwhile, both on Luzon and Okinawa, considerable Japanese opposition was overcome in the first three days of June. On Okinawa, an extreme shortage of rations for the Japanese troops was causing considerable discontent among them, something hitherto unknown. On June 3, American Marines seized the Iheya Islands, north of Okinawa; then, on Okinawa itself, they landed on June 4 on the Oroku peninsula, where a Japanese Naval Base Force of five thousand men was defending the Naha airfield. For ten days they fought with fiame-throwers, fiame-throwing tanks and explosives against a fanatical and tenacious Japanese defence—men, willing to die in their hundreds in fiames rather than give up a single cave. In the ten day battle, four thousand Japanese were killed, at a cost of 1,608 American lives. When the Americans finally penetrated the Japanese headquarters cave, which had also served as a hospital, they found that more than two hundred wounded soldiers and headquarters stafi’ had committed suicide, including the commander of the Naval Base Force, Admiral Minoru Ota.

On June 5, a typhoon ofi’ Okinawa damaged many American warships, including four battleships and eight aircraft-carriers. To compound the injury, the battleship Mississippi and the heavy cruiser Louisville were both seriously damaged by Japanese suicide aircraft. But with every set of suicide attacks, the Japanese power to sustain such a course was further diminished.

In Tokyo, at a Government conference held in the presence of Hirohito on June 8, the Japanese Cabinet resolved ‘to prosecute the war to the bitter end’. That day, on Okinawa, the Americans advanced once more, at the southern end of the island, against the Japanese fortified positions on Yuza Hill and the Kunishi Ridge; but once more they were confronted with a ferocious defender whose power to drive back the attackers was still formidable. Despite a massive American artillery bombardment, the Japanese again dug deep into the hillside; the napalm bomb was virtually the only effective means of dislodging them, or, rather, of destroying them. Yet the Japanese determination to fight back led to an enormous number of casualties among the Marines. On average, an American rifieman could expect to fight for only about three weeks before becoming a casualty. In many front line companies, every soldier was wounded, and their replacements then wounded in their turn. Some replacements were killed before they could fire a single shot.

The fall of Okinawa, 30 April to 21 June 1945

On June 10, the assault on the Japanese defences on the southern tip of Okinawa was renewed. One Marine, Charles J. Leonard, later recalled a typical incident in the fight for Hill 69, the last major Japanese outpost before Kunishi ridge. ‘I had only one grenade left,’ he wrote, ‘and it was white phosphorous. I threw it in and stood back. A huge cloud of smoke and burning phosphorous roared out of the shallow cave. A piece landed on my arm and quickly burned through the cotton cloth and started burrowing into the skin. I pulled my bayonet from my rifie and started to scrape the phosphorous off. The smell of burning flesh was nauseating’.

Leonard’s account continued: ‘I was so occupied with this problem I did not notice that a Japanese soldier was squeezing through the cave opening. He saw me and charged with his bayonet-tipped rifie aimed at my stomach. I dropped my bayonet and grabbed my rifie. I squeezed ofi’ four rounds before he hit me. By then he was dead but his bayonet slapped into the webbing of my back pack strap which was over my right shoulder. It glanced ofi’ the heavy webbing and slashed across my chest. Since my bullets had slowed his lungs there was no significant weight behind the bayonet and it did not enter my body—just cut me superficially. He had been knocked ofi’ balance and slumped beside me. I shot him four more times and continued jerking on the trigger even after the clip had been ejected past my ear’.

Thirty-nine years later, Leonard was to write of how he had looked directly into the dark eyes of the Japanese soldier as his bullets had hit him. ‘I carry that vision still’, he wrote, ‘like a photograph in my brain. I have no regrets. We were two soldiers whose job was to kill. I had done my job. He had failed to do his. At least on me. Perhaps, he had killed some of my friends. If so, they were now avenged.’

On June 10, as the Americans struggled to defeat the Japanese in the southernmost hills of Okinawa, Australian forces landed at Labuan Island, in the first stage of the defeat of the Japanese in North Borneo. In Burma, local Burmese guerrillas, led by British officers, drove the Japanese from Loilem, in the Shan mountains. In China, Chinese troops liberated I-shan, and pursued the Japanese towards Liuchow.

In Europe, the war of armies was over, but the mass movement of refugees and displaced persons had only just begun. At Soviet insistence, tens of thousands of Russians who had either fought in German units, or had been taken prisoner by the Western Allies, were returned forcibly to the Soviet Union. At the same time, from the areas under Soviet control, millions of Germans were expelled westward, as their cities and farms changed ownership and sovereignty. On June 11, the mass expulsion began, from the Sudeten mountain regions of Czechoslovakia, of more than 700,000 Sudeten Germans, who were literally beaten across the border. These men, women and children had been Hitler’s excuse in October 1938 to dismember Czechoslovakia; now the new Czechoslovak State was determined to be rid of them. Thousands had already fied, starting from the last days of the war. Hundreds had been killed on the roads as they fied, or were thrown into the rivers of their ancestral lands. What had begun as a great

Adventure for German-speaking people all over Europe, during the euphoria of Hitler’s early victories, was now one more tragic ending in a war which had seen every variety of tragedy and disaster.

In Germany, the Allied search for Germany’s wartime leaders continued; on June 14, the former Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was arrested in a Hamburg boarding house by British soldiers. Together with many of his senior colleagues of the Third Reich, he was held in prison, while preparations were made to bring him to trial.

Preparation also continued, under the supervision of the American Army, to move as much German scientific equipment, and the scientists themselves, out of those areas of the proposed Russian zone which were temporarily under American control; it was not until a few hours before the Russians were due to arrive at Nordhausen and Bleichrode, on June 20, that the last German scientists and their families were brought by train into the American zone. Within three weeks, on July 6, the American Joint Chiefs of Staff authorized Operation Overcast, to ‘exploit’ from among the German scientists ‘chosen, rare minds whose continuing intellectual productivity we wish to use’. Under Operation Overcast, 350 German and Austrian scientists were to be brought within a few months to the U nited States.

In the Far East, as part of Operation Oboe III, the Australians had liberated the town of Brunei on June 13. On the Philippine island of Mindanao, all organized resistance ended on June 18; for some while, the Japanese defenders had been forced to live on roots, and on the bark of trees. Also on June 18, American bombers began a series of attacks against twenty-three Japanese towns.

On Okinawa, the last Japanese resistance on Kunishi Ridge was being slowly overcome. On June 18 the commander of the American forces on the island, Lieutenant-General Simon Buckner, left his headquarters in the north of the island to observe the final phase of the battle in the south. As he watched the battle, he was killed by a Japanese anti-tank shell. Two other senior American officers were killed within the next twenty-four hours, the Marine Commander, Colonel Harold C. Roberts, hit by a sniper’s bullet, and Brigadier-General Claudius M. Easley. But by the evening of June 21, the Marines had reached the entrance to the Japanese command cave at Mabuni. That night, the two Japanese generals in the cave, Generals Ushijima and Sho, were served a special feast; then, before daylight, dressed in full field uniform, with swords and medals, both men knelt on a clean sheet, faced north in the direction of Hirohito’s palace in Tokyo, and, using a sharp sabre, committed suicide. In a final message, General Sho had written: ‘I depart without regret, shame, or obligations.’

More than 127,000 Japanese soldiers had been killed on Okinawa, and a further 80,000 Okinawan civilians. The Japanese had also infiicted massive American casualties during the battle; 7,613 Americans had been killed on land, and a further 4,907 in air and kamikaze attacks at sea, when thirty-six American warships had been sunk. The Japanese had lost an extraordinary number of aircraft over Okinawa, 7,800, for the cost of 763 American aircraft.

Elsewhere in the Pacific, the death toll was lower. When, on July 20, Australian

Troops landed at Miri, in Sarawak, as part of the reconquest of North Borneo, they were quickly able to overcome a small and already demoralized garrison. In the reconquest of the whole area, 1,234 Japanese were killed, at a cost of 114 Australian and four American lives.

Whether in a blood-bath, as at Okinawa, or with considerable slaughter, as on Luzon or Mindanao, or more easily, as in North Borneo, the Japanese were being driven slowly but relentlessly from their conquests. It was clear to the Japanese Government that the prospect of a heavy loss of American lives was not going to deter the continuing advance, or prevent new landings, including those clearly under preparation against mainland Japan. On June 20, Hirohito summoned his Prime Minister, Foreign Minister and military chiefs to an Imperial conference, at which he took an unusual initiative, urging them to make all possible efforts to end the war by diplomatic means. Even the War Minister and the Army Chief of Staff recognized the logic of their Emperor’s appeal.

In order to seek a negotiated peace, the Japanese Government decided to approach the Soviet Government, and to ask it to act as an intermediary. These approaches were made by the Japanese Foreign Minister, Togo, through his Ambassador in Moscow, Sato Naotake; unknown to Togo, his top-secret messages, sent by radio through Japan’s apparently unbreakable Magic system, were read by American Intelligence. Unfortunately for Japan, these intercepts made it clear to the Americans that, while Japan did want to negotiate peace with the United States, it was not prepared to accept unconditional surrender. Knowing this, the Americans were all the more determined to force Japan to its knees.

On June 24, in Thailand, British bombers destroyed the two railway bridges over the notorious ‘River Kwai’ which had been built under appalling conditions of slave labour by Allied prisoners-of-war as part of the Burma—Thailand railway.

In Moscow, June 24 saw a Victory march-past in Red Square, during which two hundred Soviet soldiers carried into the square two hundred captured German military banners, and, to the solemn roll of drums, threw them at the foot of the Lenin Mausoleum. Two days later, in San Francisco, the United Nations conference came to an end with the signature of the United Nations Charter. The maintenance of peace would be the responsibility of the Security Council, on which each of the five Great Powers, Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States, China and France, would have an effective veto.

In Prague, Emil Hacha, the President of Czechoslovakia in 1938, whom Hitler had made State President of Bohemia and Moravia, died in prison on June 27. Two days later, the new Czechoslovak Government signed a treaty with the Soviet Union, ceding its most easterly region, Ruthenia, to Russia. This was the first formal transfer of territory as a result of the Second World War; the Polish borders awaited the decision of Stalin, Truman and Churchill, who were preparing for a Big Three conference at Potsdam.

In the Far East, the Japanese continued to move Allied prisoners-of-war away from the areas on which they thought the Allies might land. Of 2,000 Australian prisoners-of-war who had been taken out of their camp at Sandakan, in North Borneo, in February, only six were still alive by the end of June, when the march reached Ranau, a hundred miles inland. On the first day of July, Australian forces, their assault preceded by a massive American aerial bombardment, landed near Balikpapan, which with its oil installations fell to them two days later; the Japanese, however, had prepared strong defensive positions in the interior; they were determined not to give up Borneo easily.

In the Philippines, a further American landing on Mindanao, near the southern port of Davao, on July 4, further restricted the area under Japanese control. On the following day, General MacArthur announced that the liberation of the Philippines was completed. That same week of Allied success against the Japanese saw the tragic end of a once twenty-three strong British Special Operations group, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Ivan Lyon, which had begun its operations behind Japanese lines on Merapas Island, near Singapore, the previous September. In a series of clashes with the Japanese, twelve of the group, including Lyon, had been killed, and eleven captured. One of the eleven died of his wounds. After six months in captivity, the surviving ten were beheaded, on July 7.

In Canada, on July 9, a British physicist working on research into nuclear fission, Dr Alan Nunn May, handed to Colonel Zabotin, a member of the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa ‘162 micrograms of Uranium 233, in the form of acid, contained in a thick lamina’—as Zabotin described it in his telegram to Moscow. From Klaus Fuchs, the Soviet atomic scientists already knew of the American experiments being carried out for the final manufacture of an atomic bomb.

Another recently developed type of bomb, the napalm bomb, was already in use against the Japanese; on July 11, and again on July 12, several thousand tons of napalm bombs were dropped on the Japanese forces still holding out on the Philippine island of Luzon, 40,000 of them in the area around Kiangan.

On July 12, on mainland China, in Operation Apple, a Chinese Nationalist commando force dropped near Kaiping, to cut the Japanese lines of communications. At all its margins, even those that had seemed most secure, the Japanese New Order in Asia and the Pacific was being eroded.

In Berlin, on July 12, Field Marshal Montgomery invested four Soviet commanders, including Marshals Zhukov and Rokossovsky, with British medals. That day, in London, the British Air Ministry launched a peacetime plan, Operation Surgeon, designed to ‘cut out the heart’ of German aviation expertise. Not only was German equipment to be brought to Britain, from the German Air Force research centre at Volkenrode, now in the British zone of Germany, but also to be brought to Britain were several German

Experts; two of them, Wernher Pinsche and Dietrich Kuchemann, were among more than twenty German aviation experts who were eventually employed at the Royal Air Force research establishment at Farnborough. Another German aviation expert, Adolf Busemann, was later to leave Britain in order to continue his research in the United States.

Those of Germany’s leading Nazis who had been captured by the Allies were now awaiting trial. On July 14 the Chicago Daily News revealed that they were being held, not in prison, but at a hotel in Luxemburg, the Palace Hotel, Mondorf. The newspaper was critical of what it saw as far too pleasant a setting for such evil men. Radio Moscow, picking up this news item, translated the hotel into ‘a Luxemburg palace’, where the Nazi leaders were ‘getting even fatter and more insolent’. In fact, they were receiving standard Allied prisoner-of-war rations, and were living amid the strictest security of stockade, floodlights, and guards with machine-guns.

As Germany’s former leaders awaited trial, one of Germany’s former allies, Italy, declared war on Japan, a final, ignominious end to the Axis which had once been so formidable a war-making combination.

The American target date for the initial invasion of mainland Japan was still November 1, a mere three and a half months away when, on July 14, American warships, among them the Massachusetts, began a series of bombardments of specific targets on the Japanese home islands. The target that day was the Imperial Ironworks at Kamaishi. On the following day, from distant Naples, the first shipload of American troops who had served in the European theatre set sail for the Pacific. They too were a part of the buildup to the November invasion.

The Japanese, aware only that the day of American landings on Kyushu and Honshu could not be very far distant, made preparations to meet the invaders, not only with the stubborn defences which they had used throughout the Pacific, but with an intensification of suicide tactics. Thousands more men were being trained for ‘kamikaze’ aircraft attacks and the equally destructive ‘kaiten’ torpedo suicide missions. In addition, a third type of suicide weapon, a suicide mine, had been devised, whereby a diver would place the mine on the hull of a ship, and detonate it, blowing himself up with the ship.

The suicide divers who were to carry these mines were known as ‘fukuryu’— crouching dragons. Their principal task would be to swim out to sea to place their mines on the hulls of the landing craft and supply ships at each invasion beach. That November, the Fukuryu began their training, walking out to sea with their mines to depths of up to fifteen metres. At the same time, experiments were made into sunken concrete shelters in which six-man squads of Fukuryu could be waiting offshore under the water up to ten hours before the invasion barges arrived.

World History

World History