(a) Operation MARKET-GARDEN

As described in Chapter V, the purpose of SHAEF’s strategy in early September 1944 was to reach the Rhine as quickly as possible on a broad front. The main thrust of the assaults was to be directed at the area north of the Ardennes. The 21st Army Group and elements of the US 1st Army were instructed to seize the Ruhr area after forming bridgeheads east of the Rhine. At the same time, units of the 12th Army Group (Bradley) were to attack in the direction of Cologne, the Saar, and Frankfurt.1942 In the light of these intentions, Montgomery’s proposal in early September to take Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem was to some extent a modification of Eisenhower’s plans, because it meant that the attack would now be directed not so much eastwards as northwards. Furthermore, the primary aim of clearing the approaches to the Scheldt would then take second place. At first, therefore, Eisenhower like his senior staff officers took a rather sceptical view of the British field marshal’s plans. Then, however, when the British 2nd Army achieved some successes against the Germans east of Antwerp and even managed to secure a bridgehead across the Meuse-Scheldt canal at Neerpelt, the Allied supreme commander realized that this was also a good opportunity to inflict a decisive defeat on the Germans along this section of the front before the onset of bad weather.1943

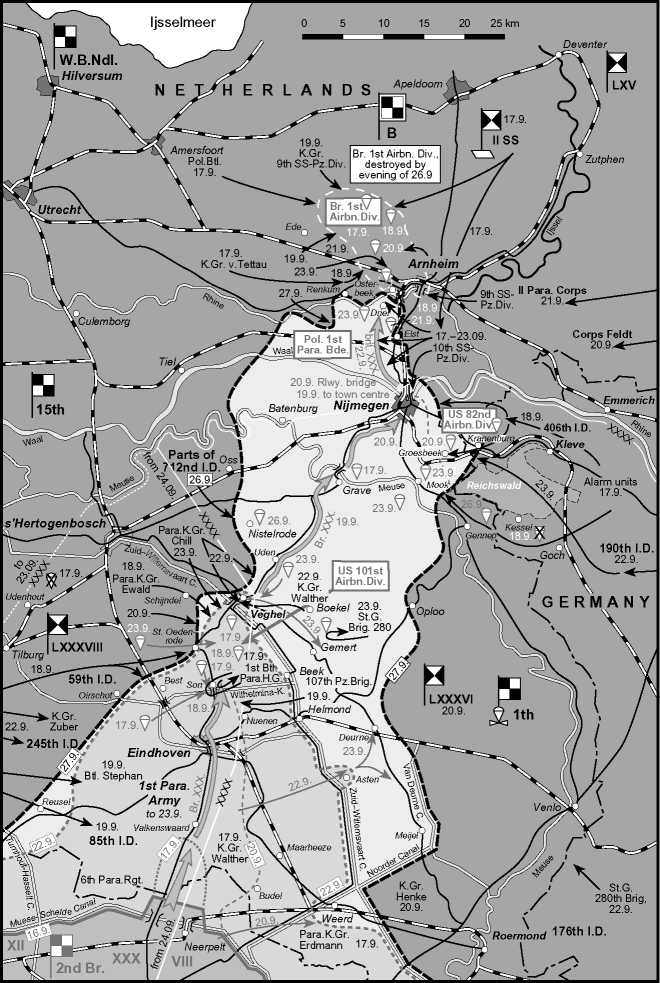

Under Montgomery’s market-garden plans of 10 September, three airborne divisions were to seize tactically important areas around Veghel/Eind-hoven (US 101 Airborne Division), south of Nijmegen (US 82 Airborne Division), and west of Arnhem (British i Paratroop Division and, later, the Polish 1st Paratroop Brigade), under the command of Lt.-General Frederick

Browning (Operation market). SHAEF put 1,546 aircraft and 478 gliders on standby in Britain to transport the 35,000 soldiers of the Allied ist Airborne Army who would be needed for this operation. They were to be protected by nearly i,000 fighter-bombers.1944

At almost the same time as the airborne operations were taking place, Lt.-General Brian Horrocks’s British XXX Corps (one armoured division and two infantry divisions) were to advance along the road from Neepelt via Veghel and Nijmegen to Arnhem (Operation garden). Its left and right flanks were to be covered by two further British corps. The purpose of this operation was to encircle all German forces in western Holland (in particular the German Fifteenth Army) by a swing from Arnhem to the River IJssel. Montgomery believed that the Canadian ist Army would manage on its own to clear the approaches to Antwerp during that same period.

British 2nd Army, for its part, was to attack further eastwards after reaching the IJssel, avoid the West Wall from the north, and then thrust into the northern German lowlands. Both Montgomery and Eisenhower saw this operation as the last chance of achieving a decisive victory before the onset of winter, and thereby forcing Germany to surrender more quickly.

Another reason for conducting market-garden was probably that the first V-2 rockets had fallen on London on 8 September. The Allies hoped that this operation would at least block any supplies for the V-2s—which they assumed to be stationed around Rotterdam and Amsterdam.1945

Eisenhower also agreed to Montgomery’s proposals because this seemed a good opportunity to deploy the Allied ist Airborne Army, something Marshall and Gen. Henry H. Arnold (C-in-C of the US air force) had been calling for repeatedly in the past. But plans to use the paratroop divisions after the breakout in Normandy—for example, west of the Seine, north of the Somme, at Boulogne, Calais, or Tournai—had been rejected again and again because of the rapid Allied advance, which meant that the airborne units’ aircraft were being used only for carrying troops and supplies.1946 Montgomery’s proposal to use all three divisions together for market-garden was now to change this situation.

The operation did harbour some inherent risks. After all, Arnhem, where the British i Airborne Division was to land, was more than 80 km away from the Neerpelt bridgehead on the Meuse-Scheldt canal, so it would take some time for Horrocks’s divisions to reach the town. It also had to be remembered that only one main road was usable for the advance, and that it crossed a great many rivers and canals. The marshy terrain and the woods around the assault axis favoured the defenders more than the attackers. That is why, even before the war, Dutch general staff officers had said it would not be possible for motorized forces to advance rapidly from Eindhoven via Nijmegen towards Arnhem. Yet the 21 Army Group planners disregarded this advice.

Another risk factor was the weather, because airborne landings, together with continuous support for the dropped units by Allied air fleets, were feasible only during good flying conditions. Montgomery, like the SHAEF officers, presumably believed that the mass deployment of airborne troops so far behind the front would shock their opponent and paralyse his ability to react for a long time. They also thought the German troops in the Netherlands would not put up much serious resistance. Obviously this was still the view when SHAEF learned from ultra on 16 September—a day before the operation began—that the 9th SS-Panzer Division was positioned near Arnhem and the ioth SS-Panzer Division was heading that way. Despite these reports, Montgomery stuck to his decision that the British ist Airborne Division troops should be dropped at Arnhem.1947

On the first day of the assault, the field marshal’s assessment of the German units’ combat strength in this region seemed by and large to be confirmed. After Allied bombers concentrated their attacks on German flak positions near the drop zones, the first wave of paratroops landed around noon on 17 September without encountering any serious resistance. They only suffered 2.8 per-cent casualties, although SHAEF had predicted losses of between 25 and 30 per cent. It seemed, therefore, that the surprise attack had succeeded. In the days beforehand, the German intelligence services had indeed been expecting Allied attacks on this front too, but they had assumed that Montgomery was more likely to advance towards the German border of the Reich and not almost directly northwards. As a result, the airborne troops managed to establish themselves firmly on the very first day and to seize important bridges and road junctions.

However, when Horrocks’s troops attacked towards the north from the Neerpelt bridgehead at around i500h that same day, they soon met with considerable resistance. They now became aware of the disadvantage that there was only one major road along which the corps’ many tanks and motor vehicles could advance. To bypass the German defensive positions by marching through marshland and wooded areas would have cost many

Source: Daily reports and situation maps, OB West, BA-MA, RH 19 IV/56 to 57 and RH 19 IV/72 K i to K 12, together with RH 19 IV/73 K i to K 7; i. e. Kelp and Schoenmaker, De bevrijding, 97, 109, 121-2, 136, 148.

Map II. VII. I. Operations market and garden in the Netherlands, 17-27 September 1944

Sources: BA-MA, Kart RH 2 W/226 and 295; Pogue, Supreme Command, Map V; Ellis, Victory, ii. 166; Stacey, Victory., Map 8.

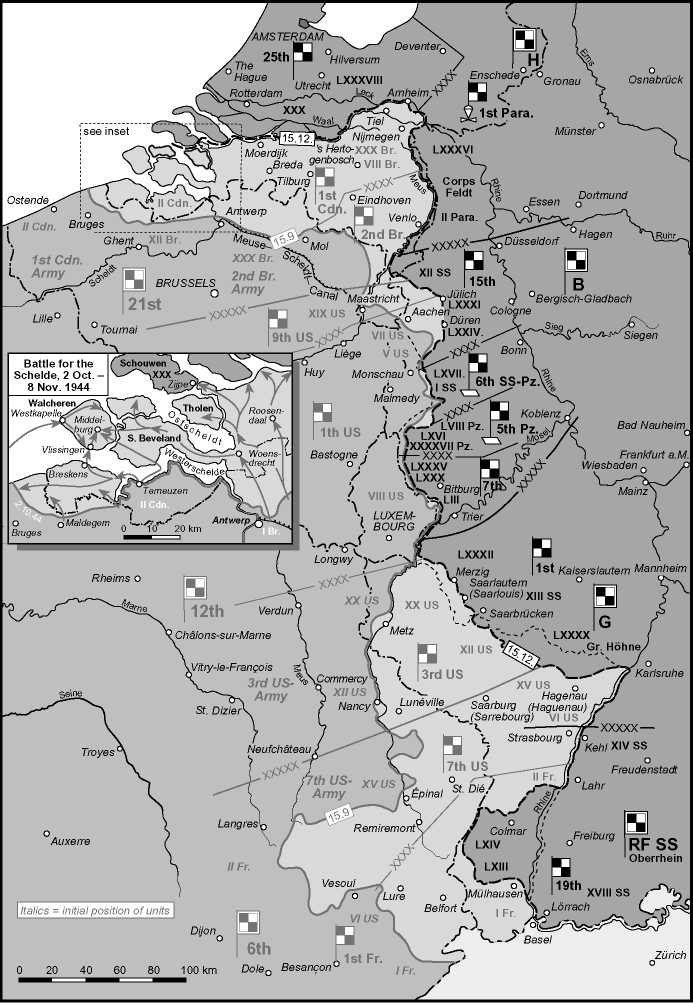

Map II. vii.2. Development of the situation, 15 September-15 December 1944

Casualties and taken a long time. Even over the next few days the British did not, therefore, manage to achieve their objectives according to the timetable set down in the operational plan. Instead of joining up with British ist Airborne Division at Arnhem within a space of two or three days, Horrocks’s units did not reach the Lower Rhine south of the town until almost a week later. Nevertheless, they managed to link up with the American airborne troops at Eindhoven on i8 September and at Grave a day later.1948 Then, however, the further advance once again proved very slow because of increasingly stiff German resistance. On 22 September units of the German Fifteenth Army and First Paratroop Army even managed to block the road along which the British were advancing at Veghel. Over the next two days the British and Americans managed to open up the road again, but they had now lost valuable time. Meanwhile the paratroops who had landed west of Arnhem were finding themselves in a precarious situation.1949 Field Marshal Model, whose Army Group B staff was positioned north-west of Arnhem, had very rapidly formed combat groups made up of paratroop and panzer units, which increasingly confined the British to the small area of ground they were holding near Arnhem. When the weather worsened on 19 September, the British found they could only sporadically supply their airborne units, drop other units there, or repulse the German attacks with their aircraft. The first elements of British XXX Corps managed to reach the Lower Rhine on 22 September, but from this position the only way to support the airborne units north of the river was by using artillery. The river crossings were already firmly in German hands.1950

Nor did the landing of Polish airborne troops south of the Lower Rhine on 21 September do much to improve the perilous situation of the British at Arnhem. Gen. Dempsey, C-in-C British 2nd Army, therefore recommended that the airborne troops at Arnhem should be ordered to break out towards the south in the event that no direct contact could be established with them. When they still did not manage to do so over the next few days, the Allies withdrew all the troops—or what remained of them—north of the Lower Rhine. They had suffered serious losses: some 6,500 soldiers were taken prisoner, wounded, or fell in action. Only 2,163 men managed to escape southwards across the Rhine. The Germans reported their losses in the Arnhem battles as 3,300 men.1951

In terms of the Allies’ original objectives, the operation was a total failure. They had not managed to cut off the German units in the western Netherlands, nor could they now even contemplate making a wide detour round the West Wall fortifications from the north. At this point it seemed impossible to envisage any real end to the war before the onset of winter. The reasons why MARKET-GARDEN failed were the poor terrain and bad weather conditions, together with the fact that the Allied commanders, and Montgomery in particular, had assessed the enemy situation wrongly. The Allies had underestimated the Germans’ combat strength. Moreover, they had not expected the German commanders to take rapid countermeasures. Nor did they take account of reports that German troops had received substantial reinforcements in the planned assault zone. Another serious disadvantage was that the Allies did not complete all the airborne landings at Arnhem on the very first day of the attack. Montgomery and his staff officers evidently believed that German resistance would be so weak that they would be able to drop the airborne troops comfortably over a period of three successive days. The soldiers who flew in later were thus up against an opposing force that was already alerted and prepared to defend itself. Added to this, Montgomery’s style of leadership was not conducive to the rapid mastery of a critical situation. Because the field marshal did not really cooperate with his HQ personnel and senior officers, each commander did what seemed right to him at the time. Also, the Allies had seen no need to establish contact with the Dutch resistance, which would certainly have been able to provide them with valuable information on the German strength in the battle zones and to support them during the critical early stage of the landings.

It is also worth noting that not much time was spent on preparing for MARKET-GARDEN. Presumably Montgomery wanted to exploit the weakness the Germans had shown so far, as quickly as he could. Clearly he also wanted rapidly to create faits accomplis; if the operation proved successful, it would make it almost impossible for Eisenhower to stop him from carrying out his plan for a separate assault to the north of the front.

Similarly, the Germans succeeded only in part with their plans to counter MARKET-GARDEN. Model was trying to hem in the Allied troops south of the Lower Rhine and to destroy them there. Yet British 2nd Army proved particularly good at defending the narrow corridor it had secured (see Maps II. IV.1-2) against German attacks, and managed to broaden it considerably towards the east and the west over the next few weeks.1952

The Dutch civilian population also suffered bitterly from the failure of MARKET-GARDEN, having hoped the Allied assault would rapidly free their country from German domination. The Dutch therefore greeted the airborne landings with open jubilation. Wherever they went, Allied soldiers were greeted with spontaneous offers of assistance. The Dutch also supported the operation by calling a general rail strike, with a view to blocking the movement of German military convoys in the Netherlands.1953

They were, therefore, deeply disappointed when the British soldiers withdrew from Arnhem again, which meant that large parts of the Netherlands were not liberated. The Germans reacted in their usual fashion: anyone suspected of supporting the Allies was executed; civilians were even summarily shot. In addition, the inhabitants of Arnhem and surrounding areas (a total of some 180,000 people) were forced to leave their homes and seek shelter elsewhere.1954 Over the next weeks and months the rail strike resulted in large parts of the western Netherlands running short of food and fuel. The Germans had also put a stop to the carriage of goods along the many canals. As a result, famine broke out in winter, and some 16,000 people died.

During the first few days of the operation, the occupying forces’ military convoys were indeed hampered in their movements by the rail strike, but very soon they managed to replace the Dutch railwaymen with Germans, so that supplies to and the mobility of the occupying troops remained largely unaffected.14

(b) The Battle for the Scheldt

Only a few days after the launch of MARKET-GARDEN, Eisenhower once again set out the fundamentals of his anti-German strategy at a conference of senior military officers in Versailles on 22 September. He emphasized that the main objective was to secure Antwerp in order to bring in supplies for the Allies. Only then would the Allied offensive plans have adequate logistical protection. Eisenhower therefore rejected Montgomery’s view that the 21st Army Group could advance towards Germany if SHAEF concentrated supplies on this army group alone. He did indeed instruct the US 3rd Army to put all offensive projects on hold for the time being, but insisted that Bradley’s 12th Army

Group must nevertheless advance towards Cologne-Bonn and Devers’s 6th Army Group towards Mulhouse-Strasbourg. This meant that, although Montgomery could expect his views to be given priority as far as the bringing-up of supplies was concerned, he could not count on claiming all the Allied supplies for his own troops.1955

After the Arnhem debacle, the favourable strategic base that should have been established for launching operations directed inside the Reich had also disappeared. Now SHAEF’s plan was to drive back the German troops at Venlo across the Meuse, in order to secure the eastern side of the corridor, as well as to clear the Scheldt estuary as quickly as possible.

Eisenhower and Montgomery had hoped that the Canadian 1st Army would accomplish this by early October; yet it soon became clear that it was not really in a position to do so. Crerar, C-in-C Canadian 1st Army, was now also struggling to cope with supply difficulties, on top of which there was clearly a considerable shortage of infantrymen in his units. Furthermore, considerable Canadian forces were occupied in trying to seize the channel ports of Le Havre, Boulogne, Dunkirk, and Calais.1956

On 29 September Eisenhower therefore ordered the 21st Army Group to concentrate all its efforts on clearing the approaches to the Scheldt. On 4 October, during another SHAEF conference, he argued strongly against Montgomery’s view that, despite the failure of market-garden, and although Antwerp could not be used for Allied supplies, it was possible to advance right into Germany. The field marshal thought the area west of the Meuse would be a suitable point for launching the attack.

When Montgomery also suggested changing the Allied command structure, Eisenhower, usually so patient, must have seen red. Montgomery had taken the view that the long front in the west, which contained so many armies, could not be overseen adequately by a single supreme commander—which amounted to open criticism of Eisenhower’s leadership abilities. Montgomery called for a local commander to be given sole competence for these operations in the case of special actions. Here, of course, he was thinking mainly of himself and his plan to penetrate into the northern German lowland plain. Presumably the British field marshal was envisaging a command structure similar to that set up at the time of the Normandy landing.

Eisenhower replied in plain words that it was now less a question of command than of finally clearing the approaches to Antwerp, a view also shared by Marshall and Brooke (the British chief of staff). Should Montgomery be unhappy with the efficiency of his leadership, however, Eisenhower said he would be quite willing to ‘refer the matter to higher authority’. Thereupon, on 16 October, Montgomery gave way. He now promised to be an obedient subordinate and to do his best to free Antwerp rapidly. All this gave the impression that Eisenhower now wanted to carry out his duties as supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe more energetically than ever.1957

Perhaps one reason for Eisenhower’s unusually direct approach was that, in his view, market-garden had delayed operations around the Scheldt approaches by two or three weeks. This was probably an underestimate, since British troops did not begin to give serious support to the Canadian 1st Army until after Montgomery’s change of heart. However, British I Corps had begun by late September to widen the corridor secured during market-garden at Turnhout, Breda, and Roosendaal. to this, the British units were able to give the Canadian troops attacking towards South Beveland adequate protection to their rear.

According to 21st Army Group’s plans, the German Fifteenth Army under Gen. von Zangen was to be attacked from the south (at Breskens) and in the east (across the Woensdrecht isthmus) in order to clear the Westerscheldt. Crerar’s units had managed to drive Zangen’s divisions back to the area north of the Leopold Canal by 20 September, but their thrusts from Antwerp towards Woensdrecht did not begin until 2 October, and the advance against the German bridgehead south of the Westerscheldt at Breskens not until four days later.1958

Meanwhile the Fifteenth Army had enough time to withdraw the majority of its troops to the area north of the Westerscheldt (Walcheren and South Beveland), where it took comprehensive defensive measures. By 23 September it had transferred 82,000 men, 530 guns, 4,600 motor vehicles, and 4,000 horses there. Despite massive support from the Allied air force, the Canadian troops were therefore slow to reach the isthmus west of Woensdrecht, incurring heavy losses, and did not arrive until late October. Moreover, it took Crerar’s units more than two weeks to force the remnants of the Fifteenth Army in the Breskens bridgehead to surrender. By 3 November, 12,707 German soldiers had been taken prisoner there.1959

Only a few days earlier, on 25 October, Allied troops had begun a pincer attack on the South Beveland peninsula held by the German Fifteenth Army. While the Canadians advanced westwards from Woensdrecht, British units landed on the southern tip of the peninsula. On 31 October the Allies took South Beveland after bitter battles and then proceeded to attack Walcheren, the last German bastion along the Westerscheldt. British bombers had destroyed the dyke on the island some weeks earlier, which meant that large areas of Walcheren were flooded. Nonetheless, the defenders did not give up the fight. Thereupon British commandos, who had sailed from Ostend and Breskens on i November, attacked the German defensive positions at Flushing and Westkapelle. That same day, British infantry units advanced from South Beveland to Middelburg. On 8 November the battle for the sea approaches to Antwerp came to an end here too and Zangen’s Fifteenth Army troops had to withdraw to the northern bank of the Meuse at Zijpe and Moerdijk. Once British troops had also managed to drive the Germans back across the Meuse north of Breda and s’Hertogenbosch, the front extended along the Waal at Tiel and northwards past Nijmegen almost as far as the Lower Rhine.

The battle for the Scheldt had cost Canadian ist Army, which was supported by British but also American and Polish units, a total of i2,873 dead, wounded, and missing. On the other hand, over the period from i October to 8 November the Allied troops had managed to capture a total of 41,043 German soldiers.1960

As soon as the Westerscheldt had been freed, the British navy began to clear the sea route of mines. On 28 November, that is, nearly three months after the liberation of Antwerp, the first Allied convoy of ships reached the port. The Allies estimated that from then on they would be able to unload up to 80,000 t of supplies a day. This led to a substantial improvement in their supply situation, as it meant far fewer goods needed to be carried overland.

Since the German troops could now no longer control access to Antwerp directly, they attempted to make the port unusable by launching V-weapons, beginning as early as 13 October. By the end of the year Allied military losses in and around Antwerp amounted to 734 dead and 1,078 wounded. In military terms, however, the use of V-i and V-2 weapons proved far less successful than the Germans had expected. Because these weapons were far from accurate, they destroyed only a few port installations.1961 (c) Allied Operations up to the Start of the Ardennes Offensive While the battles for Arnhem and the Scheldt were being fought, the Allies also tried to break through to the Rhine on the fronts further south, or at least to inflict heavy losses on the Germans. However, the outlook for this did not look very promising, because the worsening autumn weather benefited the German defenders.

Furthermore, the Germans had now managed to bring up troops and materiel, while the Allies were slow to consolidate their supply system. Added to this, the Allies gradually found themselves critically short of infantrymen, which led SHAEF to take some unusual measures. Rather like their opponents even before the landing, in early November the Allies also began to comb out their rear zones (Communication and Interior) for enough men to make up for at least the most acute shortages.1962

Despite these hardly favourable circumstances, Eisenhower decided at the beginning of October to continue the assaults. He temporarily shifted the main thrust of the operation to Bradley’s command area. Montgomery’s 2ist Army Group confined itself to attacking the German bridgeheads on the Meuse at Venlo. By 14 November it had managed to drive back the German First Airborne Army to the eastern bank of the river, apart from one bridgehead at Venlo which was not seized until early December.1963

Meanwhile, the left flank of Bradley’s front was greatly strengthened in the new thrust area when Gen. William H. Simpson’s 9th Army was brought up. In October the Americans also managed to encircle Aachen, forcing the German troops in the town (some 3,000 men) to surrender on the 21st of that month. During the battles, 85 per cent of the town was destroyed.1964 The further assault by the two US armies (ist and 9th) towards Cologne and Bonn, which resumed on 16 November, came up against determined resistance from German troops. Despite intensive bombardment of the German positions, it took the Americans a long time to drive back the Army Group B units.

OB West had even assembled Fifth Panzer Army units in this section of the front, in expectation of an Allied attack; these units had in fact been intended for deployment in the Ardennes offensive planned by Hitler and OKW. By the beginning of this operation, on 16 December, the US troops had advanced no further than the River Rur at Jiilich and Diiren. In Bradley’s view, if they were to continue to advance on the other bank of the river, they would first have had to seize the Rur and Urft dams. Yet they did not manage to do so until the beginning of the Ardennes campaign, in spite of deploying four American divisions. The US 1st Army suffered particularly heavy losses in the battles in Hurtgen Forest south of Diiren (21,000 men between 16 November and 16 December).1965

Further south, however, the Allies proved more successful. Before the end of October the US 3rd Army and 6th Army Group had managed to drive the German Army Group G units back to the foothills of the Vosges at Luneville and east of Epinal. When the Sixth Panzer Army’s counterattacks failed there, Gen. Hermann Balck, commanding Army Group G, withdrew his troops to the passes through the Vosges. On 8 November the US 3rd Army continued its assaults, encircled Metz ten days later, and then forced the Germans to hand over the town on 22 November. The Allied air forces managed to destroy German relief units while they were still marching up. Thereupon the German First Army withdrew to the West Wall between Merzig and Saarlautern (Saarlouis). Patton did not manage to advance to Saarbrucken as intended, however, and his troops did not succeed in forming a bridgehead at Saarlautern until early December.1966

On 13 November, only a few days after the beginning of US 3rd Army’s assault, units of Devers’s US 6th Army Group also launched operations against the southern section of Army Group G (in particular the Nineteenth Army). Five days later units of the French 2nd Armoured Division had penetrated to the Zabern valley, on 23 November it liberated Strasbourg, and then thrust forward as far as the Rhine at Kehl. At the same time, US 7th Army was driving the Germans back eastwards across the Vosges near St-Die.

The Allies now also succeeded in breaking through the German positions in the Belfort Gap north of the Swiss border. On 20 November they reached the Rhine and two days later seized Mulhouse. The Nineteenth Army did, however, manage to hold a large bridgehead at Colmar. The French 1st Army proved too weak to advance northwards along the Rhine at this stage.1967 The North African soldiers in De Lattre de Tassigny’s units found the atrocious weather particularly dispiriting; their morale also began to suffer because many of them had the impression they were being made to run all the risks on behalf of comrades from the mother country who seemed rather reluctant to join the French army. Looking only at the infantry units, this impression may not have been entirely inaccurate. On the whole, however, as SHAEF noted as early as i November, the rearming of the French units had proceeded entirely accordingly to plan. The French army now had as many as 230,000 men, many of whom came from the mother country.1968

Hitler was furious at the defeat in his First and Ninth Army areas, and ordered a court-martial investigation. The committee of inquiry set up by the Reich Court-Martial found that ‘leadership and reporting errors’ had occurred during the battles in the Army Group G area. According to OB West (Rundstedt again since 5 September), however, the army group units had been weakened so severely by the high losses and withdrawals of motorized units that they had had little capacity to resist the far superior Allied forces. On 23 December Hitler then decided not to order a formal trial; meanwhile, however, on 26 November, he had already put Himmler in full command of all German troops between Karlsruhe and the Swiss border (Army Group Upper Rhine). Evidently, he had more confidence in the ability of the Reichsfuhrer SS and chief of police to organize defence against the Allies in this sector of the front than in that of his Wehrmacht generals.1969

The strength of German resistance, which made itself felt by the second half of September 1944 at the latest, led the Allied leaders to review their strategy in the west several times. The main question was how the war could be brought to a victorious end as quickly as possible. Eisenhower had told Marshall at the end of October that he regarded the early opening of the port at Antwerp as one of the most important preconditions for conducting a successful war against Germany itself. Only when the logistics problems had been resolved could decisive attacks be launched against the German forces in the west. In answer to Marshall’s question whether one could count on hostilities coming to an end by i January 1945, he therefore expressed serious doubts. Nor did the joint planning staff of the British COS dare to make any concrete predictions at this stage, although the officers presumed they could force the Germans to surrender between 3i January and mid-May i945. Since the Allies did not manage to clear the approaches to Antwerp until late November 1944, they now confined their plans to forming a bridgehead across the Rhine by the beginning of i945.

Apart from sorting out the supply situation called for by Eisenhower, SHAEF continued trying to destroy the German strategic infrastructure by a sustained bombing campaign. It therefore decided at the end of October to give priority to attacking the Germans’ oil industry, together with their transport system.1970

When it became generally apparent to the Allies in late November that they would not even be able to break through at Aachen in the near future, this led to the bitterest quarrel of all between Eisenhower and Montgomery. The latter, certain that he would be protected from the rear by Field Marshal Brooke, the British chief of staff, once again urged that the command be divided between one commander north of the Ardennes and one to the south. He felt that the strategy pursued by SHAEF and Eisenhower to date, namely to attack on every front, had failed because there had been no main thrust. Eisenhower defended himself against this criticism by arguing that he could not accept Montgomery’s description of the Allied successes since Bradley’s breakout in Normandy as failures. In a letter dated i December he reminded the British field marshal that the Allies were still operating successfully. For instance, he wrote, between 8 November and the end of the month the US 3rd Army had taken 25,000 prisoners, and ist and 9th Armies combined had taken 30,000. In view of SHAEF’s future projects, he thought that limited operations should be conducted on all sections of the fTont for the time being, while at the same time preparing for a major assault. The Allied supreme commander was tactful enough not to mention, in his communication to the field marshal, that it was his critic Montgomery who was largely to blame for the fact that it had taken so long to be able, by clearing the approaches to the Scheldt, to conduct large-scale operations.31

The Allied military leaders agreed to meet in Maastricht on 7 December in order to discuss all these problems at the highest level. At this conference, Montgomery found himself faced with a combined front of both American and British officers (Tedder, Bradley, and Smith), all of whom supported Eisenhower’s position. So he seemed to have very little prospect of pushing his views through. In the event, Montgomery did not achieve much more than what had already been decided: priority for 21st Army Group, although without making the Ardennes the boundary between the 21st and 12th Army Groups as he had wanted. Instead, the boundary line was to run north of Maastricht. Similarly, Eisenhower once again rejected the idea that US troops should be prevented at all cost from advancing towards Frankfurt. As before, Montgomery was very firmly against crossing the Rhine by that route, because in his view the terrain east of the city was not suitable for deep-ranging advances.32

A further conference held in London scarcely a week later, between Eisenhower and Tedder on the one side and Brooke and Churchill on the

Pogue, Supreme Command, 307 ff.; Ellis, Victory, ii. 138 and 170, together with Gilbert, Second World War, 616 (bombing).

31 See Pogue, Supreme Command, 312 ff.; Ambrose, Supreme Commander, 547 ff., and Ellis, Victory, ii. i66 ff.

32 See Ellis, Victory, ii. 549ff.; Pogue, Supreme Command, 3i6; SHAEF, Notes on Meeting at Maastricht, 7 Dec. 1944, PRO, WO 219/216, and 21st AGp, Montgomery to COS, 6 Nov. 1944, ibid., WO 205/5B; here the field marshal reacted to the news that Gen. Patton wanted to advance towards Frankfurt with the words: ‘All very interesting!’ Other, produced little change in SHAEF’s strategy. Early in November, in the light of the slow Allied advance in western Europe and the standstill on this front, Churchill had suggested a meeting with Roosevelt, in order to get things moving again. But the American president declined to attend. In his view, everything was still going according to plan in Europe, and he tried to encourage Churchill by saying that a breakthrough would come soon. When Field Marshal Brooke severely criticized Eisenhower’s conduct of the war in western Europe during the London conference, Churchill finally sided with the American supreme commander. After assessing the situation in realistic terms, the British prime minister presumably saw little chance of achieving any fundamental changes in the Allied conduct of the war in western Europe.

These incidents show once again that, unlike Churchill, Roosevelt had no ambitions to intervene in the details in a theatre of war; except when major decisions had to be taken, he preferred to leave the planning and conduct of military operations to officers he trusted.1971

At least, after all these discussions, Montgomery could once again count on priority being given to his operations against the Reich in terms of the allocation of supplies and of support from the air. Moreover, the right flank of 2ist Army Group would now be guarded by the US 9th Army. SHAEF planned to begin these operations in the first half of January 1945. At the same time, however, Eisenhower ordered that the American 3rd and 7th Armies should attack in the direction of the Saar and the Palatinate (the upper Rhineland) as early as 19 December. Further south, US 6th Army Group was to destroy the German bridgehead at Colmar. The US ist Army was ordered to continue its assaults and to seize the Rur and Urft dams, in order to prepare the ground for the operations against Bonn and Cologne. The Allies had 64 divisions and seven brigades in western Europe that they could deploy for all these operations.1972

2. The Ardennes Offensive (Operation wacht am rhein)

(a) German Plans and Preparations

Initially, the Allied intentions described above were thwarted by Operation wacht am RHEIN (Watch on the Rhine). As early as August 1944, after Bradley’s troops had broken out in Normandy, Hitler and the OKW began to give thought to launching a large-scale counter-offensive. in mid-September, when the Allied advance had slowed down considerably, Sixth Panzer Army was formed in preparation for the German offensive, led by SS-Oberst-gruppenfuhrer and Waffen-SS Gen. Sepp Dietrich, who was tasked with refreshing the exhausted panzer units so that he could then use them for assault operations. The headquarters and commanders involved were not, however, told what concrete objective these measures were intended to achieve; at this stage Hitler shared his views regarding an operation in the west only with the officers closest to him, whom he informed that his military objective was to retake Antwerp. The plan was to remove the Allies’ most important supply base, while at the same time facing them with a ‘new Dunkirk’. In this way the German dictator intended finally to take back the initiative in the west. Once the Allies had been decisively defeated, the Reich would be in a position to face up to the expected Soviet winter offensive.1973

In late September Keitel and Jodl were ordered to draw up plans for the operations in the west. In early October the Wehrmacht operations staff produced a few outline plans for assaults along the entire western front. According to Warlimont, the officers finally concluded that an offensive across the Ardennes between Monschau and Echternach, using two panzer armies, would offer a good opportunity to reach Antwerp rapidly. They believed the Allies (the US 1st Army) were thin on the ground in this section of the front, with its difficult terrain, so that the prospects of an attempt to break through the Allied positions looked very promising.

Meanwhile, on 3 September Hitler had once again appointed Rundstedt as OB West, while Model remained C-in-C of Army Group B. On 12 October Keitel ordered Rundstedt to make ready for an operation east of the US 1st Army’s sector, advising him that it was of the utmost importance to keep all these measures secret. Not even he was yet told the true objective of the preparations.1974

It was not until ten days later that Hitler himself told the chiefs of staff of OB West and Army Group B (Westphal and Krebs) of his intentions. In early November Rundstedt gave his opinion of these plans; he agreed with Hitler about the Wehrmacht operations staff’s proposal, while proposing another assault from Aachen in a westerly direction where, as has been outlined above, the Allies had already deployed numerous divisions in order to break through to the Rhine. OB West considered that the first priority was to crush these. Field Marshal Model, whose Army Group B was to conduct Operation wacht AM RHEIN, reviewed Rundstedt’s plans again a fortnight later. He proposed encircling Allied units near Aachen (US 9th and 1st Armies and British 2nd Army) while they were still east of the Meuse and then destroying them, before advancing further towards Antwerp. The advantage of this, in his view, was that it would release the German divisions currently fighting east of Aachen so that they could be used for wacht am rhein.

Hitler, Keitel, and Jodl, however, thought these proposals would detract from the real objective, and rejected the alternative plans. Zangen’s Fifteenth Army, which was now facing the Americans at Aachen, should in their view be used only to guard the northern flank of Sixth SS-Panzer Army, while Army Group H forces should not advance southwards from the Netherlands until later in the course of wacht am rhein. In the end, both Rundstedt and Model declared themselves entirely happy with this solution.1975

When Hitler gave the order to deploy on io November, it became clear that the German leader once again wanted to ‘stake everything on one card’, as Jodl put it. Unconcerned by the constant Allied assaults, he believed that a concentrated thrust by two panzer armies (Sixth SS and Fifth) towards Antwerp could separate all their opponent’s units north of a line through Bastogne-Brussels-Antwerp (20-30 divisions of British 21st Army Group, together with the US ist and 9th Armies) from the American armies positioned to the south, and destroy them. Hitler was confident that this would turn the tide of the war.1976

The necessary forces were due to be fully deployed by 27 November. At the end of the month, however, this deadline had to be postponed, first to 10 December and finally to 16 December, because Bradley’s and Devers’s offensives had prevented the Germans from bringing up forces to the front in the west in time, especially motorized units. The bad roads and shortage of transport facilities and fuel also made it difficult to deploy these forces rapidly. Another factor that had to be taken into account was the weather: in view of the Allies’ air superiority, operations could begin only during a period of bad weather. It also took the Germans a long time to take up their initial positions, because convoys could usually move only at night for reasons of secrecy.1977

The importance Hitler attached to Operation wacht am rhein is clear from the fact that he left his headquarters in Berlin on 10 December and moved to the ‘Eagle’s Nest’ (Adlerhorst) bunker near Bad Nauheim, in order to be as close as possible to the coming scene of action. On ii and 12 December the German dictator assembled all officers involved in the operation, from division commander upwards, in the ‘Eagle’s Nest’ to explain the importance of the forthcoming battles to them in person. He kept impressing on his subordinates that this was a unique chance to end the ‘unnatural coalition’ of their opponents by ‘a few very heavy blows’. With a mixture of truth and lies, Hitler endeavoured to convince the officers that the Wehrmacht was still superior to the Allied soldiers. Many of the officers present took their supreme commander’s words as great encouragement.

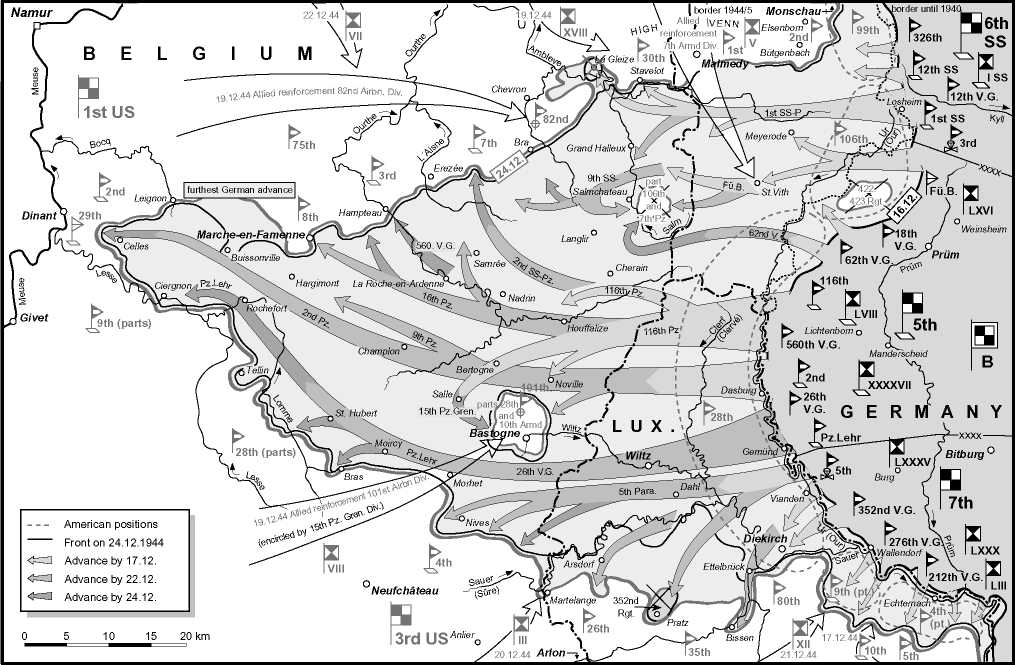

According to the concrete plans set out by Hitler and the Wehrmacht executive staff, on i6 December three armies (Sixth SS-Panzer, Fifth Panzer Army, and Seventh Army) under the high command of Army Group B were to attack on a broad front of some 170 km between Monschau and Echternach. The first wave was made up of 200,000 men (13 Volksgrenadier and five panzer divisions), with 600 armoured vehicles, supported by 1,600 artillery guns.1978 In total, Model had 19 divisions (including seven panzer divisions) from the three deployed armies available for this operation. He could also draw on up to ten further divisions (including two panzer divisions) from other sections of Army Group B’s front and from the reserve, as reinforcements.

The plan was that the Sixth SS-Panzer Army would spearhead the main attack with an assault between Monschau and Losheim. A few days later, SS-Panzer divisions were to cross the Meuse between Liege and Huy and then advance towards Antwerp. The left flank of these assault forces was to be guarded by the Fifth Panzer Army, led by Gen. Hasso von Manteuffel. Its task was to cross the Meuse at Dinant and then advance towards Brussels and Antwerp. Seventh German Army (under Gen. Erich Brandenberger) was detailed to guard its left flank by thrusts towards Arlon.1979

One of the biggest headaches in this operation was the shortage of deployable air forces, which Hitler had admitted in his speeches in the ‘Eagle’s Nest’ on ii and 12 December, without, however, suggesting a solution. As mentioned earlier, the German commanders wanted to launch the attack during a time of bad weather, to give at least some temporary protection from the Allies’ air superiority. In addition, some 1,770 fighters—as much as two-thirds of the total German air strength—and 700 other aircraft were concentrated on airfields in the west. They were instructed to protect the heads of their own panzer columns against enemy air strikes, and to attack Allied airfields in the vicinity of the area of operation.1980

During the preparatory stage for wacht am rhein Hitler hit on the idea of putting SS and Wehrmacht soldiers who could speak English behind enemy lines. Dressed in US uniforms and equipped with Allied vehicles, they were to sabotage the Allies’ defensive measures and generally sow confusion. The 2,000 or so men assembled in what was called ‘Panzer Brigade 150’, under SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer Otto Skorzeny, were ordered to seize the Meuse crossings and carry out other acts of sabotage. OB West held detailed discussions on 9 November about this operation, codenamed GREIF (griffon), which was in breach of the international laws of war. A further operation, codenamed ST(Osser (sparrowhawk), was to be carried out by airborne troops—this time in German uniform. The paratroops were ordered to occupy major roads and passes in the High Venn, north of Malmedy, in order to prevent a flank attack on the Sixth SS-Panzer Army from the north.1981

After assessing the enemy situation, the staffs of OB West and Army Group B believed they would manage to inflict a surprise attack on their enemy on 16 December, thanks to their many concealment measures. They assumed that, because of the effects of this surprise strike and their numerical superiority in ground troops in this area, they would encounter little resistance until they reached the Meuse. Studies carried out by the staff of Army Group B on 10 and 15 December show that the officers assumed there were only about 550 Allied tanks in the area in which the three German armies would attack. However, they also reckoned that in view of the Allied offensives in the northern and southern Ardennes, the Allies had a total of 2,000 tanks along the entire army group front. Yet Model’s staff thought it unlikely that strong contingents of mobile Allied divisions could reach the zone of attack during the first few days of the operation. In particular, they did not expect the British staff to react rapidly or flexibly, so they did not expect the 21st Army Group to take countermeasures until the German panzers had nearly reached Brussels. Nor did they believe that units could rapidly be brought up from the US 6th Army Group, because it was closely engaged with German troops. At most, it was felt, the US 9th and 1st Armies could free up to five divisions relatively quickly, since they were not expecting any major German counter-attacks around Aachen. Army Group B assumed that in any case Fifteenth Army and paratroops (Operation StOOsser) would be able to prevent these US divisions from advancing southwards. It was thought highly unlikely that the Allies would bring up other reinforcements until long after the Germans’ own units had crossed the Meuse. According to German reconnaissance reports, their enemy had few reserves in depth. None of these studies considered the likely effects of the Allies’ air superiority on the course of the operations.1982

Model was not at all concerned about reports that on 13 December the Americans had moved armoured fighting vehicles to the assault zone, and that shortly before they had conveyed troops from Devers’s 6th Army Group northwards to US 3rd Army’s area of command. Nor was the assault date postponed when it became apparent that it was frequently impossible to bring up troops according to plan because of the vigorous Allied attacks on other sections of the front in the west. Some units, especially in the Fifth Panzer Army, therefore arrived at their deployment area rather battle-weary and in great haste. Very young and inexperienced soldiers were often assigned to the divisions to replace the losses. When the soldiers occupied their standby positions, the measures to ensure secrecy the Germans had imposed upon themselves proved to be another disruptive factor. Many units were not allowed to move into their deployment areas until the night before the attack, which meant they had almost no chance of reconnoitring the terrain ahead of them.

Notwithstanding these problems, the German side still counted on success, because the Wehrmacht felt it was far superior to the Allied officers and headquarters staff in terms of the tactical and operational leadership of units. At all events, Model informed Hitler on 15 December that the army group was now entirely set to seize Antwerp, and at the beginning of the attack Rundstedt announced that it was now a question of doing ‘everything’ for ‘our Fatherland and our Fiihrer’, and that 16 December would also bring ‘the start of a new phase of the entire western campaign’.1983

(b) Allied Reconnaissance Findings

A day before, Montgomery had asked his supreme commander whether he could spend his Christmas leave in England. Eisenhower agreed, because in his last situation assessment before the German attack Montgomery had informed the Imperial General Staff that ‘there is nothing to report on my front or the front of the American armies on my right. I do not propose to send any more evening situation reports till the war becomes more exciting.’ The other senior officers on the Allied side proved equally unsuspecting.1984

It is quite astonishing that the Allied staffs, who had been quite successful so far in assessing the enemy situation, could have been so wrong on this occasion. After all, they had received numerous indications of an operation of this scale, in spite of the German measures to maintain secrecy. In fact the Allies had known since August 1944 that German Army Group B was preparing a counter-offensive. Nor were they unaware that the Sixth SS-Panzer Army was being brought up or that the Germans were seeking to free up motorized units from certain sectors of the western front. At the same time, they had received reports that many German combat forces were being concentrated around Dusseldorf and east of Aachen. This picture of German preparations for an offensive was completed by the many signs of road and rail convoys west of the Rhine at Koblenz.

A few days before the attack was launched, US VIII Corps positioned southwest of Bastogne received reports from deserters and civilians that the Germans were deploying substantial numbers of tanks and motor vehicles, as well as bridging equipment, in the area round Bitburg. It was also noted that early in December the German U-boats in the Atlantic were sending out far more frequent weather reports than before. This too was an unmistakeable sign that the other side was up to something along this front. Eventually, reports trickled in that the Germans were planning to operate behind Allied lines in the near future (the plan for GREIf).1985

Naturally these reports gave rise to all sorts of suppositions on the Allied side. Gen. Kenneth Strong, the SHAEF intelligence officer, believed a few weeks before the operation began that the reported enemy activities could mean one of several things. The Germans might be refreshing their troops east of the relatively calm front at the Ardennes in order to use them on the eastern front. These standby units could also enable Rundstedt to block an Allied breakthrough at Aachen. Nor did Strong exclude the possibility that the Germans were preparing for an offensive through the Ardennes. The intelligence officer passed on his thoughts to Bradley and Smith, SHAEF chief of staff. Eisenhower did then feel some concern about the low troop density in the US 1st Army sector in the Ardennes. Bradley shared his supreme commander’s anxiety, but believed the risk could be taken, because the strong offensives under way north and south of the area in question would surely prevent their opponent from attacking in the Ardennes. Nonetheless, he promised Eisenhower he would deploy a few divisions as reinforcements in this area. In fact, however, on i6 December the German attackers were faced with only five US divisions (including one armoured division) with 83,000 men between Monschau and Echternach. They themselves had more than 420 tanks and other AFVs, together with 504 artillery pieces. On the day of the attack, in numerical terms, Model’s troops had 2.4 times as many men, 1.4 times as many armoured units, and 4.8 times as many guns as the Allied forces.1986

The Allied staffs saw an attack in this particular area as rather unlikely mainly because, although the reports they had received made it perfectly conceivable that the Germans could attack even before Christmas—if only to boost morale among their people and on the front—they thought there was

Source: OKW, Situation maps, BA-MA, Kart RH 2W/606 to 627.

Map n. VII.3. The Ardennes offensive, 16-24 December 1944

Source'. OKW, situation maps, BA-MA, Kart RH 2W/626 to 708.

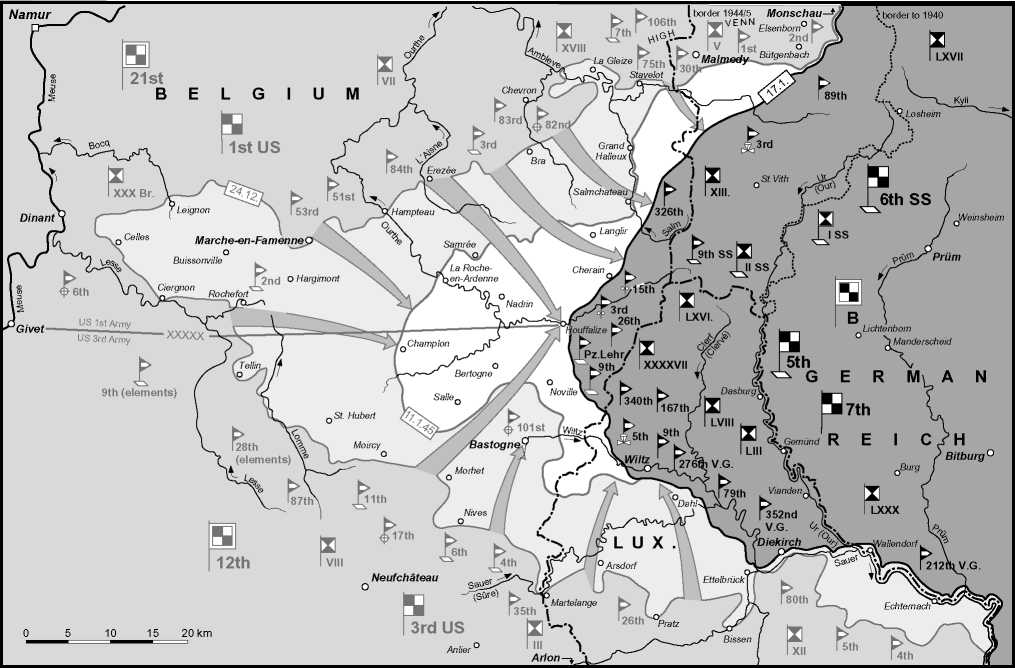

Map n. VII.4. Ardennes offensive: Allied counter-attacks, 24 December 1944-17 January 1945

Little fear of much more than a local ‘showdown’ since the state of the Germans’ reserves, especially fuel stocks, would prevent them from embarking on any large-scale operations. The only attack that would make any military sense, in view of the expected Allied breakthrough, would be east of Aachen (Strong’s second alternative). The Ardennes, on the other hand, would be less suitable for large-scale operations because the roads there would be difficult to use in winter. So the Allies tended to regard the reported German troop activity in the Eifel area as a fairly normal part of the process of refreshing burnt-out units.1987

All this seemed entirely logical. What the Allies did not, however, take into account was the fact that the other side was no longer really thinking logically or acting rationally. The Germans did not even manage to formulate any halfway plausible strategic objectives for the alternative operations proposed by Rundstedt and Model—not to mention the plans mooted by Hitler and the generals around him and their orders to stake everything on this operation. Also, the Allies were unaware that in fact Hitler and the OKW were behind the assault plans and not Rundstedt, whom they considered far more cautious. He was merely the willing executor of his superior’s orders. When they assessed their enemy the Allies, as Hugh Cole put it so well, were looking into a mirror in which they only saw the reaction to their own intentions. These were, in the main, to plan and carry out offensives during that period, while largely ignoring defensive considerations. Several Allied commanders thus believed the Germans would, given their generally hopeless situation, harm themselves more than the Allies if they did actually attack. In a sense they were to prove right; but at first the Allies had to suffer bitter setbacks.

One factor that may have played its part in the Allied military leaders’ thinking was that they had received no ultra reports that indicated a German offensive. This was because during the preparatory stage for wachtamrhein the Germans had stopped using radio for their communications. The Allied commanders evidently assumed that if they heard nothing from ultra, there could be no imminent danger, and thus did not take all the other reconnaissance reports indicating an imminent assault very seriously.1988

(c) The Battles in the Ardennes from Mid-December 1944 to Early January 1945

On 16 December towards 0700h, after an hour of artillery bombardment, Model’s troops attacked between Monschau and Echternach. The Sixth SS-Panzer Army was to cross the Meuse between Huy and Liege and then push forward to Antwerp. Dietrich’s troops did manage to seize the outposts of US V Corps, yet their attempted breakthrough failed because of the grim

American resistance. In particular, the tactically important hills around Elsenbom and BUtgenbach remained in Allied hands. Further south at Losheim, however, SS units managed to advance a little further westwards that day and over the next few days. But there too, the German assault quickly came to a standstill around Malmedy and Stavelot. This meant that for the time being the plan to push through the High Venn, seize crossings over the Meuse, and finally take Antwerp had failed. Operation ST(Osser to seize the Venn passes also failed; poor weather conditions made it impossible to drop the paratroops according to plan, and most of them were taken prisoner by US troops.1989

In the course of the attacks by Sixth SS-Panzer Army there were many breaches of the international laws of war, beginning with those committed by a 1st SS-Panzer Division (Peiper) combat group. By 19 December its victims included 308 US soldiers, who were captured and then shot, as were 130 Belgian civilians. News of these atrocities spread like wildfire among Allied troops, and they too now sometimes shot German soldiers after they had surrendered.1990

Unlike Dietrich’s rather unsuccessful panzer army, Manteuffel’s troops (the Fifth Panzer Army) exploited the moment of surprise much more effectively; they managed to break through the defensive system of US VIII Corps (under Middleton) between St-Vith and north of Wiltz, and to advance westwards over the next few days. Fifth Panzer Army even managed to encircle an American division south-east of St-Vith and on 18 December forced it to surrender, taking more than 8,000 US soldiers prisoner. Yet despite this success, American troops held the key traffic junctions at Bastogne and, initially, also at St-Vith. In the southern sector of the assault zone, Seventh Army (under Gen. Erich Brandenberger) achieved only relatively minor breakthroughs between Echternach and Nives.

Although the Allied air force found it very difficult to support its own ground troops because of the bad weather, the German panzer units could make only slow progress, hampered by waterlogged roads, poor communications, and soon also a shortage of fuel. One major setback for them was that they could not take St-Vith until 21 December, and did not take Bastogne at all; this was firstly because of the resistance put up by the US troops, who often had to act on their own and fight without receiving any orders from their commands.1991 Secondly, it was because the Allied supreme commander and his staff had realized how important the traffic intersections were for the Germans and therefore reacted quickly to the attack. As early as 16 December, after in-depth consultations with his SHAEF staff officers, Eisenhower had ordered that all available airborne and armoured units should immediately be moved to strengthen these important areas—even though at that stage few reports of the actual scale of the attack had come through to Allied headquarters. Unlike several other senior officers, Eisenhower did not believe that this was a small operation but assumed it to be a large-scale German offensive.

World History

World History