In September 1948 the stevedores poisoned in Sydney took legal action in a quest for some form of compensation and writs were issued in the New South Wales Supreme Court.' The first case heard was that of Stevedore Flanagan who had been on the Friday day shift. He sued the Idomeneus shipowners China Mutual Steam Navigation Company Ltd and the Ocean Steam Ship Company Ltd for damages for negligence. Those companies, in effect, sued the Commonwealth of Australia for an indemnity or contribution, believing that the Commonwealth had indeed played a part in the gassing. The two shipping companies traded under the name of Alfred Holt & Co.

New South Wales Supreme Court.

In law, stevedore Flanagan was known as an ‘invitee’ (onto the ship) of the defendant companies. Flanagan’s legal representatives argued that a duty to exercise ‘reasonable care’ existed to prevent damage from an unusual danger of which the occupier knew or ought to have known and of which the plaintiff was ignorant.

Mr Clemens, representing the plaintiff Flanagan, submitted a three-fold argument: 1. the failure to warn the plaintiff of the danger; 2. failure to prevent escape of gas in the hold; and 3. failure to provide protection (gas masks) with suitable instruction as to their use.

The Commonwealth (termed the 3rd party) pursued a strategy designed to show that the damage was the result of a storm that had hit the Idomeneus during her voyage to Australia. The Commonwealth legal team also set out to verify that all the known tests had been conducted. In addition, the Commonwealth sought to show contributory negligence by the plaintiff as Flanagan had not worn a gas mask when he should have done so.

The first day of the trial was 26 June 1950 and stevedore Flanagan was called to testify. He made a poor start and his testimony was confused. He described the smell in the hold and the subsequent attention drawn to the bloodshot appearance of the stevedores’ eyes. He recalled that the men had a lunch break at 12.00, came back at 1.00 pm and then worked in No. 3 hold. He described the struggle to reach home and the period he had spent in hospital. During cross-examination Flanagan was told that the hold had in fact been closed at 10.30 am on Friday. Flanagan was actually relating the events of the night shift in which he had played no part. He had worked on Friday morning. Flanagan’s testimony had been clouded by discussions with his colleagues and he had become confused over the intervening seven years. Three members of the Melbourne contingent were the next to testify, wharfies Cook, Alexander and Duck. They described the gassing in Melbourne and their resultant pain and suffering.

Le Fevre spent only a matter of minutes in the stand. Under crossexamination by Mr Ferguson (who was acting for the defendants) as to why he had recommended the use of masks he replied, ‘Because of the occurrences in Melbourne, of which I take it you have information, which had occurred and in which in no way proved indubitably to me that mustard gas may have caused it, but it may have been due to mustard gas.’

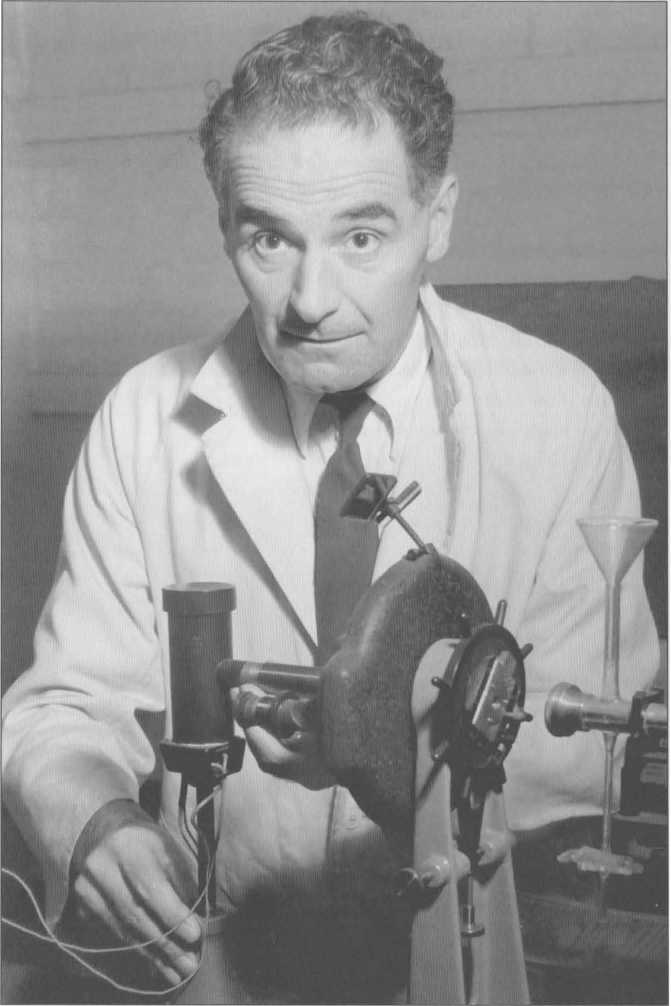

Professor Raymond Le Fevre [National Archives of Australia).

This was the first time in seven years that Le Fevre had admitted the possibility that the Melbourne incident may have been in any way related to mustard gas. Ferguson was clearly taken aback, for he then asked, ‘What was the last part?’ wheteby Le Fevre repeated the admission: ‘. it may have been due to mustard gas..Ferguson pressed, ‘Did you at that time have any opinion as to the cause of the sickness in Melbourne?’ ‘Not a definite opinion, I was inclined to the belief that mustard was the cause,’ was Le Fevre’s answer.

The door was ajar, a significant development from the evidence previously garnered under oath. At the RAAF Court of Inquiry Le Fevre had strongly argued that mustard was never a possibility in Melbourne. After denying it under any circumstances he later admitted that it was a possibility in Sydney but only after the leaking drum had been discovered at the end of the unloading process. Now he had stated that it was a possibility in Melbourne.

The critical question then arose: could Le Fevre have been certain that mustard gas had contaminated the stevedores in Melbourne prior to the commencement of unloading in Sydney? The implications were seismic, both morally and legally. If the RAAF had known or strongly suspected this to be the case, then they were responsible for both the tragic death and the catastrophic health effects on the wharfies in Sydney. Had military secrecy led to the death of Williams? If so, an innocent man had suffered and died needlessly. There could be no excuse, despite the fact that this was a wartime situation and the importation was a highly secret business. And there was also an obvious solution to the situation, one that was implemented after the wharfies had refused to unload the cargo. A RAAF crew in full protective gear acting under military orders should have been brought in to unload No. 1 hold, as had eventually happened at Glebe.

Ferguson let the matter drop temporarily but returned to it later in crossexamination. This occurred while he was again exploring the question of who was in control of the cargo, which was central to the case. He asked Le Fevre, ‘After the Melbourne incident, where the people went down. You were inclined to the view, weren’t you, that it was not mustard gas at all that caused it?’ And again he received an unexpected reply, ‘Officially, but in my own heart... ’ Ferguson cut him off and pursued the opening. ‘Officially you expressed that view?’ and was answered, ‘The whole matter was graded as secret, at that time, so for the purposes of public discussion I spoke about the possibilities of soda ash and these other chemicals having been responsible, but in my own mind I thought mn. stard was at the bottom of the whole thing.’

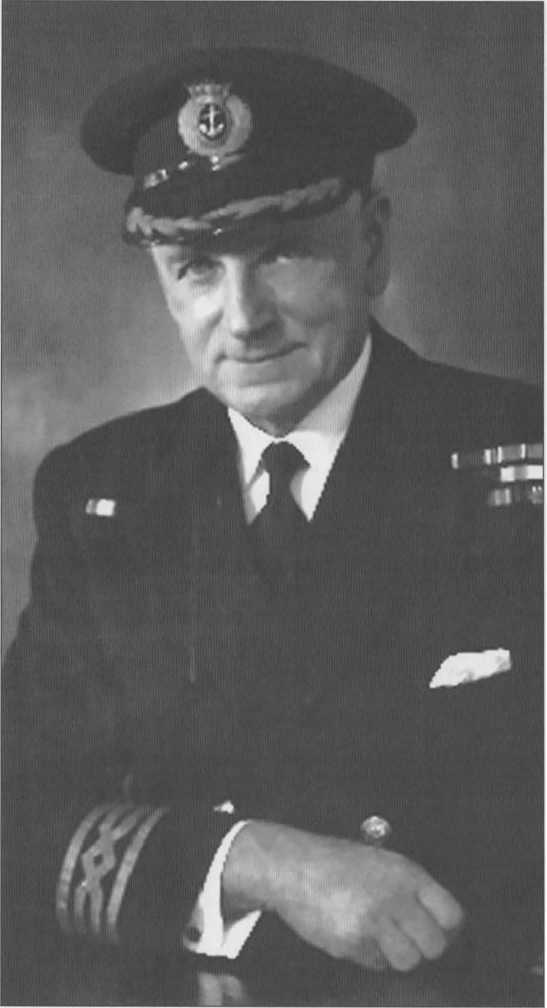

Walter Francis Dark (Arthur Dark).

Under oath Le Fevre stated that he had always believed mustard to be at the bottom ‘of the whole thing’. After seven years the truth had finally emerged.

By the time he reached Sydney Le Fevre had become convinced that mustard gas was responsible for the Melbourne injuries, but he had been constrained by military secrecy. Concerning the issue of the Allied use of mustard gas he admitted, ‘Oh yes. Britain was a signatory to the Geneva Convention and so on. We were just not supposed to know anything about it.’

That there can be no doubt that secrecy was the central issue was confirmed in the following trial which featured stevedore Pearce as the plaintiff. Le Fevre was asked: ‘And, of course, your reason for making that public utterance [that it was not mustard that caused the Melbourne casualties] was the security reasons?’ Le Fevre replied, ‘It was.’ He was also asked, ‘That is the way you desired to deal with it, to disguise the fact - I can quite appreciate why - for security reasons, that the men had been affected by mustard gas?’ Le Fevre answered, ‘Yes.’ These are among the numerous admissions in the series of three trials by Le Fevre that he had believed mustard gas to be the cause but had been unable to reveal his conviction to anyone, including his chemist colleague, McKenzie, whom he had assisted in assessing the safety of the holds.

In the third and final trial, with wharfie Swinton now as the plaintiff, Le Fevre admitted to telling an untruth at the Sydney conference when the ship had initially attived. When asked, ‘As far as you were concerned, at the conference you expressed the view that it was not mustard gas but these chemicals [soda ash]?’ Le Fevre answered, ‘'That is so — that was the story that I was then generally adopting to practically everybody that was not entided to know that the Australians were receiving a cargo of this noxious chemical.’ Ferguson again sought clarification: ‘Of course, the reason for that was, as you say, security reasons?’ Le Fevre replied, ‘Two reasons: security was the predominant one, and the second one was that I could then proceed to make the right recommendadon for mustard gas on the wrong reasons — even if they were the wrong reasons.’

Le Fevre believed that he could protect the stevedores from the mustard gas fumes by recommending they wear gas masks for protection from other chemicals. Although this would have protected the face and respiratory system, the men were given no reason to use them. In any case the mustard vapour would still penetrate all the other exposed areas of skin. As the stevedore supervisor Captain Grose had stated, he would have insisted that the men use the masks had he known of the existence of any dangerous free gas in the hold. However this had been categorically denied throughout the whole process.

World History

World History