As Allon prepared his plans for a major offensive in the Negev, a very intricate operation was carried out under the very noses of the Egyptians. The ‘Yiftach’ Brigade moved to the Negev through the Egyptian lines to relieve the ‘Negev’ Brigade, which had borne the brunt of the fighting in the south for the previous nine months. Both sides endeavoured to improve their positions during the truce, and fighting broke out as the respective opposing sides resisted such attempts. A typical battle was the one that took place in the area of Khirbet Mahaz, a hill overlooking the main road running from north to south through the Negev, and which was within artillery range of the airfield at Ruhama, a vital supply link for the Israeli forces in the Negev. After a fresh force from the ‘Yiftach’ Brigade had occupied the area of Khirbet Mahaz, the Israeli positions were

Unsuccessfully attacked seven times by Egyptian forces, particularly by the 6th Infantry Battalion, whose operations officer at the time was a Major Gamal Abd al Nasser. (When he assumed the Presidency of Egypt after participating in the Revolution of the Free Officers that deposed King Farouk in 1952, Nasser was to describe how the idea of a revolution germinated within him and his colleagues of the Free Officers movement during the long nights in the field in Palestine, and particularly when he was later besieged in the ‘Faluja pocket’.)

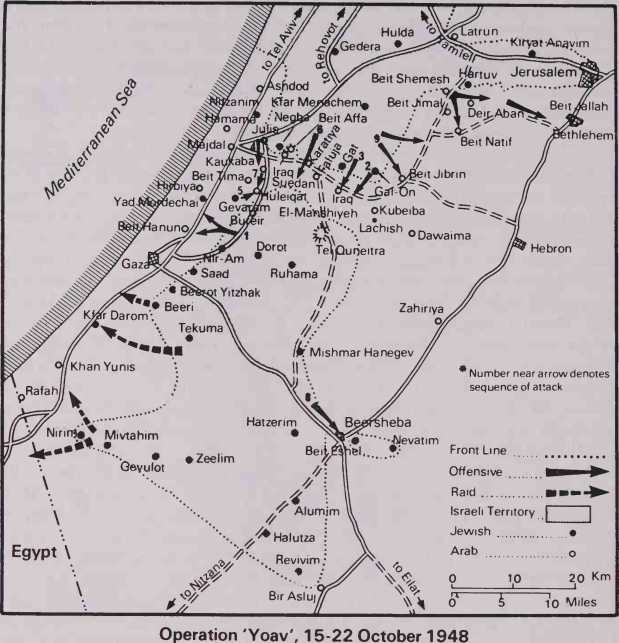

The Israeli offensive against Egypt in the south was codenamed Operation ‘Yoav’. Under Allon’s command were the ‘Givati’, ‘Negev’ and ‘Yiftach’ Brigades, in addition to two battalions from the 8th Armoured Brigade. (At a later date, the ‘Oded’ Brigade was moved from the northern front to take part in the operations.) Allon’s plan was to force open a corridor to the Negev, cut the Egyptian lines of communications along the coast and on the Beersheba-Hebron-Jerusalem road, isolate and defeat the Egyptian forces in detail, and drive them out of the country.

On 15 October, an Israeli supply convoy under United Nations supervision (in accordance with the agreed terms) set out on its way to the Negev, through the Egyptian lines at the ‘junction’. As anticipated, the Egyptians opened fire on the convoy, but the incident was merely a convenient signal for operation ‘Yoav’ to commence. That evening, Gaza, Majdal and Beit Hanun were bombed, and part of the Egyptian Air Force at El-Arish was put out of action. The commando battalion of the ‘Yiftach’ Brigade mined the railway between El-Arish and Rafah and various roads in the Rafah-Gaza area, and harassed Egyptian installations and camps. At the same time, two battalions of the ‘Givati’ Brigade forced a wedge southwards to the east of Iraq El-Manshiyeh, thus cutting the road between Faluja and Beit Jibrin. On the morning of 16 October, a tank battalion of the 8th Armoured Brigade, supported by an infantry battalion of the ‘Negev’ Brigade, launched a major attack against Iraq El-Manshiyeh in an attempt to open the corridor to the south-east. This attempt failed because of the lack of experience of the Israeli forces in coordinating armour and infantry: much of the armoured force was damaged when it was caught exposed in an artillery ‘killing ground’ previously prepared by the Egyptians, and the Israeli force was obliged to withdraw. In the course of the action, one of the two Cromwell tanks that had been acquired from the British Army was damaged, and the second Cromwell was involved in the task of extricating it from the battlefield. Very heavy losses were incurred in this attack, which had all the indications of slovenliness, lack of co-ordination and poor overall command. Of the total attacking force, only about 50 men managed to make their way back to the Israeli trenches. In addition to the heavy casualties, four Hotchkiss tanks of the small Israeli tank force were lost, and all the remaining tanks were damaged.

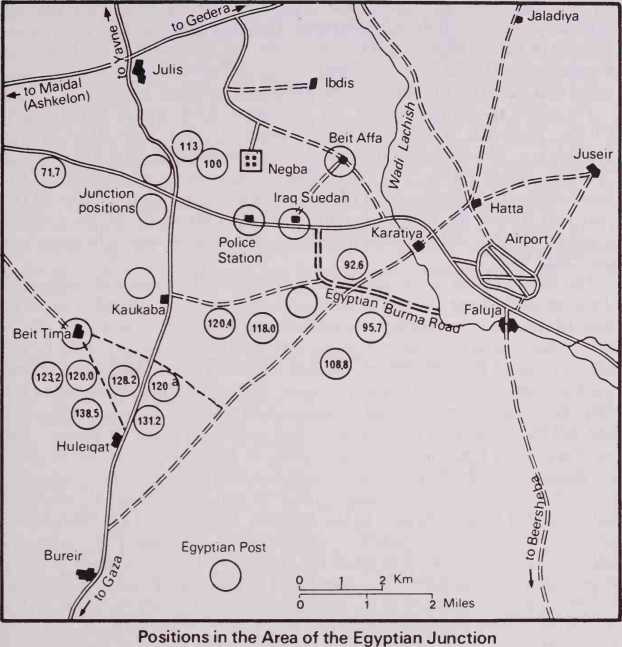

Allon drew his conclusions from this defeat and decided to return to the area near the ‘junction’ in an endeavour to break through in the area of Huleiqat. The Egyptian defences around the ‘junction’ were based on the Iraq Suedan fortress and consisted of Hill 113 and Hill 100 overlooking the ‘junction’ in the north, two mutually-supporting positions to the west held by a company and, to the south, the fortified hilltop villages of Huleiqat and Kaukaba, which were held by a reinforced company of Saudi Arabians. Allon decided to concentrate his attack on Hill 113 and the ‘junction’ strongholds, a battalion of the ‘Givati’ Brigade being assigned the task of capturing these vital points. Each position was attacked by a company advancing under the cover of artillery fire, following diversionary attacks designed to give the impression that the main attack would come from the direction of the Negev, to the south. The Egyptians were taken by surprise when the main Israeli attack came from the opposite direction. On the night of 16/17 October, the Israeli forces stormed the positions in bayonet attacks and, by midnight, following a fierce hand-to-hand battle. Hills 113 and 100 were captured. The attack on the ‘junction’ positions ran into trouble, the Egyptian resistance being more determined and protracted, but by dawn on 18 October both positions were in Israeli hands. The Egyptians counterattacked four times.

But in vain. That night, the ‘Givati’ units exploited their success further by capturing Kaukaba, but an attack by the 1st Battalion of the ‘Yiftach’ Brigade on Huleiqat failed. The planned corridor to the south remained blocked.

Meanwhile, the ‘Yiftach’ Brigade forces, which had succeeded in cutting the coastal road at Beit Hanun, threatened the Egyptian forces to the north with complete encirclement. The Egyptians began to evacuate the Ashdod and Majdal areas, using an alternative route along the beaches, and they succeeded in concentrating the evacuated brigade in the area that later became known as the ‘Gaza Strip’. The reaction on the part of the other Arab countries to the plight of the withdrawing and encircled Egyptian forces led to the inevitable inter-Arab recriminations, and this convinced the Israeli Command that other Arab armies would not intervene to help the Egyptians. Accordingly, the ‘Oded’ Brigade was moved south from Galilee, and was thrown into an unsuccessful attack on the Egyptians in the hilly area of the Kharatiya bypass. With pressure developing at the United Nations for a new cease-fire, Allon decided to concentrate all his efforts on opening the corridor to the south by cracking the ‘hard nut’ at Huleiqat. Despite the heavy losses and exhaustion of the troops, Allon decided that the task would be carried out on the night of 19/20 October by the battle-seasoned ‘Givati’ Brigade. The result was to be one of the most fiercely-fought battles in the Negev.

The Huleiqat defence system was manned by a reinforced Egyptian battalion and included a Saudi Arabian infantry company backed by a heavy weapons support company (armed with machine-guns, mortars and Bren Gun Carriers). To wrest this complex from the enemy, the 2nd Battalion of the ‘Givati’ Brigade was reinforced by an additional company from the 4th Battalion. Commanding the 2nd Battalion of the ‘Givati’ Brigade and in charge of the operation was Zvi Tzur, later to rise to the position of Chief of Staff of the Israel Defence Forces in 1961. (A very able administrator. General Tzur was to be General Dayan’s right-hand man during his period as Minister of Defence from 1967 to 1974.) The six hills held by the Egyptians were mutually supporting, and the problem of the Israeli attackers was to isolate each one and then to reduce them individually. The initial bayonet assault on the hill held in part by the Saudi Arabians, took the position by storm. A considerable quantity of equipment was discovered there, including some thirty Vickers machine-guns, which were immediately put to use by the Israeli forces, who turned the hill into a fire-support base. On all six hills, the fighting was characterized by bitter hand-to-hand combat, with the trench systems being cleared by repeated bayonet and grenade attacks. In the fighting for the last hill, ammunition ran out and men were locked in desperate ‘cold-steel’ encounters - Saudi Arabian soldiers even resorting to biting their attackers!

Thus did the Huleiqat complex fall to the ‘Givati’ attack and, on. 20 October, the road to the Negev was finally opened. Near Huleiqat today stands a monument bearing the insignia of the ‘Givati’ Brigade and the inscription: ‘As you travel southwards don’t forget us.’

An attack mounted simultaneously to take the Iraq Suedan police fortress on 20/21 October failed for the fifth time, again with serious losses. However, following up the Huleiqat success, Allon immediately prepared a task force to move on Beersheba, with the purpose of isolating the eastern Egyptian force in the Hills of Hebron and cutting its lines of communication: once fragmented, the Egyptian forces in the Negev could be dealt with in detail.

The force that moved on Beersheba consisted of major elements of the 8th Brigade, the commando battalion and two other battalions of the ‘Negev’ Brigade. At dawn on 21 October, the Israeli forces approached Beersheba from the west, while a diversionary operation was mounted from the direction of Hebron to the north. After fierce fighting, the 500-strong Egyptian garrison broke and, by 09.00 hours that morning, Beersheba — capital of the Negev — had surrendered to Israeli forces. The eastern part of the Egyptian Army was by now dismembered, with its main supply lines cut. In fact, the Egyptian expeditionary force was now broken

Up into four isolated forces: one brigade in the Rafah-Gaza area; one brigade about to withdraw southwards from the Majdal area; a complete brigade of approximately 4,000 men, under the command of the Sudanese Brigadier Said Taha Bey, confined in the so-called ‘Faluja pocket’; and some two battalions isolated in the Hebron-Jerusalem area.

To relieve the Faluja pocket, the Jordanian Arab Legion commander, Glubb, proposed a battalion-sized operation: but inter-Arab rivalry prevailed — Abdullah had no intention of relieving the Egyptians. On 22 October, Israeli forces took the village of Beit Hanun and tightened the pressure on the Egyptian lines of communication to Ashdod. During the next two weeks, the Egyptians completed the evacuation of the Ashdod area and Majdal, retiring into the general area of what was to be known as the ‘Gaza Strip’.

The Israeli forces in the Judean and Hebron Hills meanwhile expanded the area under their control in the southern Jerusalem Corridor south to Beit Jibrin, thus completing the encirclement of the Faluja pocket. On 9 November, the Iraq Suedan fortress was finally captured by units of the 8th Armoured Brigade, under Yitzhak Sadeh. The mistakes of the past were avoided this time. In the afternoon, with the setting sun blinding the defenders, the fortress of Iraq Suedan, known as ‘the monster on the hill’ and having resisted so many attacks and caused so many casualties, was softened up by the heaviest concentration of artillery that the Israelis had yet managed in the War, including newly-acquired 75mm guns, light and heavy mortars and machine-guns. The roof was swept clean by machine-gun fire, and every aperture in the building was engaged by point-blank artillery fire. After two hours of concentrated, non-stop fire, infantry, half-tracks and two tanks reached the fortress wall and breached it. They found the Egyptian garrison stunned and in shock as its soldiers emerged to surrender. ‘The monster on the hill’ had finally been subdued. As a result, the Faluja pocket was reduced to the area between Faluja and Iraq El-Manshiyeh, which continued to be held by the besieged brigade until the armistice agreement between Israel and Egypt, which was signed on 24 February 1949.

Hitherto, the commander of the Faluja pocket. Brigadier Said Taha Bey, had refused offers to meet the Israeli commanders, but now he met the southern front commander, Yigal Allon, at the village of Gat. Alton’s offer to allow the Egyptians full military honours and a free return to Egypt if they surrendered, was refused. Said Taha Bey maintained that, while he knew the position was hopeless, his task now was to save the honour of the Egyptian Army. The Egyptian Government, replied Allon, was not worthy of as brave an officer as Taha Bey.

To reinforce the Israeli units on the southern front, the ‘Golani’ Brigade was now brought down from the lush green hills of Galilee to the barren desert of the Negev. The ‘Givati’ Brigade — which had borne the brunt of the fighting in the northern Negev and had performed magnificently — was relieved and replaced by the ‘Alexandroni’ Brigade which, from mid-November, was entrusted with enforcing an effective siege of the pocket and frustrating the numerous attempts made by the Egyptians to bring in

Supplies by parachute or camel convoy. A plan to help the besieged forces break out to the Hebron Hills was clandestinely brought through the lines by a British officer of the Arab Legion, Major Lockheed. However, the supreme command of the Egyptian forces rejected it, maintaining that it was impracticable. They were also innately suspicious of any plan in which a British officer, albeit as an ally, was involved. Besides, the pocket was pinning down considerable Israeli forces. An attack by the ‘Alexandroni’ Brigade was beaten off on the night of 27/28 December. Characterized by numerous errors and ineffective co-ordination and communication, the attack was rapidly fragmented and unified command lost. Some of the isolated Israeli units were wiped out. The attack was a disaster, and a morale booster for the besieged Egyptians. Henceforth, the Faluja brigade remained under siege without any further Israeli attacks until the end of the war.

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)