The position of the Diadochi in their respective kingdoms was long ambiguous. Although Ptolemy had been ruling Egypt as its king de facto since 323, he did not feel secure enough to advertise this publicly. For a number of years documents during his reign were dated according to the formula attested at Pap. Eleph. 1 1-2: "in the seventh year of King Alexander, son of Alexander, and in the fourteenth year of Ptolemy the Satrap" (i. e., 310; the regnal years of Alexander IV are counted from Philip III Arrhidaeus' death in 317). Officially, then, Ptolemy maintained the fiction that Alexander IV was ruling a unified empire in which he, Ptolemy, was merely a satrap. The fiction existed in the first instance for the benefit of the Macedonians in Ptolemy's employ, especially the soldiers - Ptolemy was sure of their adherence to the house of Alexander the Great, less sure of their adherence to him.

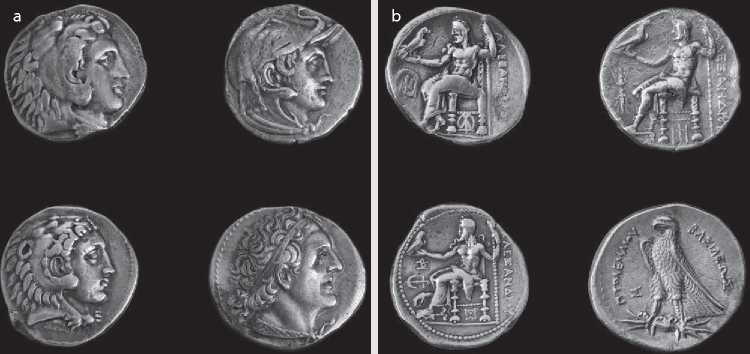

The same principle emerges from the coins Ptolemy minted in these years (see Figure 20.1). Coins, because they got into everyone's hands, were rulers' best means of putting out their message in an age without "photo ops," "sound-bites," and press releases. And the message which Ptolemy put out until circa 307 can be seen on the top right coin in Figure 20.1.

The legend on the coin reads "of Alexander," and the head is that of Alexander the Great himself, who is wearing an elephant scalp (a reference to the conquest of India). Alexander the Great was dead, but not forgotten by the Macedonians in Egypt who honored his legacy and were willing to obey the man who governed them as a satrap in the empire which Alexander had fashioned and over which Alexander's son now reigned. Because Ptolemy's rule rested on the fact of Alexander's conquest, it should not surprise that Ptolemy drew on Alexander's achievements in order to legitimate his own rule in the eyes of his (Macedonian and Greek) subjects.

The other Diadochi followed much the same pattern, as the coins of Seleucus and Antigonus Monopthalmus in Figure 20.1 show. On both coins Alexander wears a lion's skin as Heracles; the inscription reads "of Alexander."

Figure 20.1 Four coins of the Diadochi: the obverse (“heads”) of a given coin in the left-hand image corresponds to the reverse (“tails”) in the same position in the right-hand image. Clockwise from top left: tetradrachm of Antigonus Monophthalmus (M0rkholm,

Nr. 84, circa 307; inscription on reverse: “of Alexander”); tetradrachm of Ptolemy I Soter (M0rkholm, Nr. 90, circa 319-315; inscription on reverse: “of Alexander”); tetradrachm of Ptolemy I Soter (M0rkholm, Nr. 97, after circa 307; inscription on reverse: “of King Ptolemy”); tetradrachm of Seleucus I Nicator (M0rkholm, Nr. 87, after 312; inscription on reverse: “of Alexander”). Source: National Museum of Denmark

The coins, incidentally, are far more than just historical evidence. They are works of art, prime examples of portraiture. When the HeNenistic kings began putting their own images on coins, the art of portraiture quickly reached impressive heights.

World History

World History