After the 4th dynasty the state was run by an increasing number of bureaucrats, who built an increasing number of tombs, which were decorated and furnished by a proliferating group of highly skilled artisans centered around the Memphis court. As families of officials and priests continued in their offices, the bureaucracy kept on expanding (although evidence of this - titles inscribed in tombs - was probably inflated). Naguib Kanawati (Macquarie University) has argued that eventually, in the late 5th and 6th Dynasties, fewer resources may have been available for tombs of lower - and then middle-status officials.

Later Old Kingdom private tombs are found throughout Egypt, but the highest status Memphite tombs, for members of the royal family and high officials, were usually located near each king’s pyramid. Tombs of high officials had multi-roomed mastabas covered with reliefs. Some tombs had many statues, including painted ones of the tomb owner or a husband and wife pair, sometimes with their much smaller children, in the closed serdab. Many of the tomb reliefs are scenes of “daily life,” including farming and craft activities. Scenes of offering-bearers with quantities of food and drink were in addition to real food, small models of food, and model servants performing food preparation activities in the tomb. Most tomb goods, especially jewelry and inlaid furnishings, were usually robbed, but they were often depicted in scenes.

In reliefs the tomb owner is usually shown in a larger scale than anyone else, symbolic of his relative importance. Above the false door of the tomb chapel was a carved relief of the tomb owner seated before an offering table, with the offering formula text (hetep di nesu) on the lintel. Titles and names of the tomb owner were carved around the false door, to identify the tomb owner’s status in the afterlife, and sometimes there were longer biographical inscriptions.

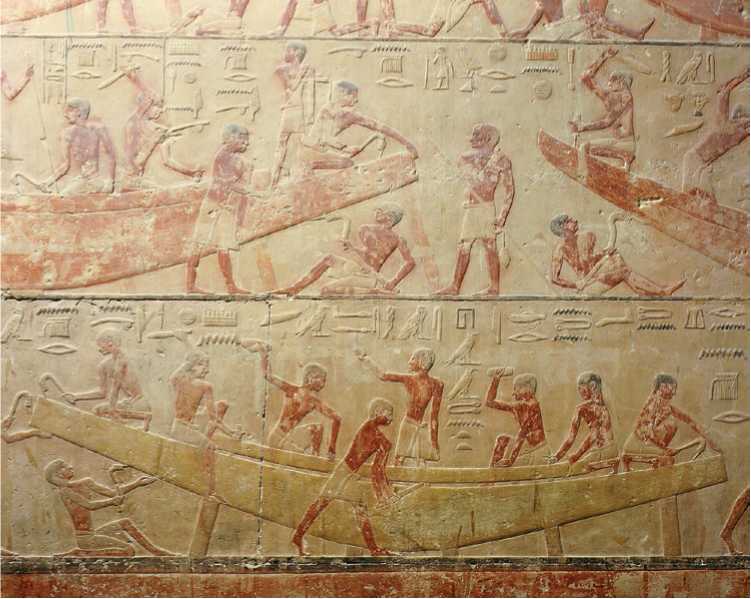

Some large family mastabas at Saqqara of the late Old Kingdom have multiple serdabs and burial shafts for the different family members - and up to 40 rooms decorated with reliefs. To the north of Djoser’s Step Pyramid are a number of well-preserved tombs, including that of a high 5th-Dynasty official named Ti, excavated by Auguste Mariette in 1855. Ti was married to a royal princess, and among his titles was “Overseer of the Sun Temples” at Abusir. The largest interior space in Ti’s mastaba is a columned court, in the center of which is the entrance to the subterranean passage to the burial chamber. Scenes in fine low relief decorate the walls of the mastaba’s interior rooms (Figure 6.16). In one scene Ti and his wife, who has her own offering niche in the tomb, are entertained by singers and musicians playing the flute and harp. Reliefs of animals, both domesticated and wild, contain very life-like details, including geese being fattened by force-feeding, and a cow, assisted by a farmer, giving birth to a calf. In a scene of Ti in a papyrus marsh, two foxes look for birds’ eggs. Craft scenes include those of ship-builders, carpenters making furniture, and women weaving linen.

The Saqqara tomb of Mereruka, who was the son-in-law of King Tety (6th Dynasty), was discovered by Jacques de Morgan in 1893. Near Tety’s pyramid, the mastaba of this tomb contains 33 rooms and corridors, some of which were for Mereruka’s wife, Hertwatet-khet, and his son, Mery-tety. Reliefs in the tomb include an animated desert scene with longlegged tjesem hounds (similar to greyhounds) hunting wild cattle, hares, and a lion, and Mereruka hunting in a papyrus marsh filled with birds, fish, and a hippopotamus (Figure 6.17). High-status Egyptians hunted for sport, and clearly wished to continue such activities in the afterlife. Some very curious scenes in this tomb also suggest attempted domestication of wild animals, including tethered gazelles and a hyena being force-fed. Such experiments, which are also known from other tombs, were not successful, however.

By the mid-5th Dynasty provincial administrators/governors (nomarchs) began to be buried in their provinces, not in Memphis, and later in the dynasty a new office appeared, that of governor/overseer of Upper Egypt. The provincial administrators were paid by the crown in the form of local land where farmers/workers lived, and food and goods were produced. In the 6th Dynasty, these offices became inherited positions, along with the associated land, and governors also began to hold important priestly titles. Thus administrative and economic control of the central government waned in the provinces (mainly in Upper Egypt) - and the increasing power of these provincial governors is reflected in their tombs.

Figure 6.16 Painted relief with scenes of boat construction from the 5th-Dynasty tomb of Ti, Saqqara. Source: The Art Archive/Alamy.

Figure 6.17 Relief scene of hunting in the desert, from the Sth-dynasty tomb of Mereruka, Saqqara.

In the Middle Cemetery at North Abydos Janet Richards (University of Michigan) has excavated the large mastaba tomb of Weni the Elder, whose long biographical inscription was found by Auguste Mariette in 1860. Weni the Elder’s career as an official spanned the reigns of the first three kings of the 6th Dynasty, and his biographical text provides important information about the increasing power of this provincial center in the late Old Kingdom - and the erosion of central power. The context of this inscription was unknown until Richards located the tomb. Her excavations have also revealed the monumental context of Weni’s burial: a mastaba ca. 30 x 30 meters, to the northeast of which is a chapel where new reliefs and inscriptions have been found. Subsequently, Richards has also excavated the large mastaba tomb of Weni’s father, the Vizier luu. These two monumental mastabas are located within a large field of many smaller ones.

Although mastaba tombs were built in upper Egypt, many of the larger tombs of nomarchs from the late 5th Dynasty onward were carved into the cliffs beyond the floodplain to either side of the Nile. Faq;ades of these tombs were cut to resemble a mastaba, with interior rock-cut rooms. Offering chambers were carved with false doors and often had rock-cut pillars and statues in niches. The burial chamber was also rock-cut, at the bottom of a shaft or ramp. In larger tombs there could also be additional rooms, including storerooms and serdabs. Decoration of the tomb was in relief scenes similar in themes to those of “daily life” found in Memphite tombs.

Rock-cut tombs at Aswan dating to the 6th Dynasty were carved in three rows on a sandstone cliff to the north of Elephantine Island, and mastaba tombs have been discovered to the east, closer to the river. Some of the more elaborate rock-cut tombs had an exterior courtyard and causeway leading to the valley. Biographical inscriptions in some of these tombs are especially informative about Egyptian relations with Nubia at this time. One of the Aswan governors, Harkhuf, who was also “Keeper to the Door of the South,” left inscriptions in his tomb about his four overland expeditions (by donkey caravan) to the land of Yam, probably in Upper Nubia. Serving under King Merenra and then Pepy II, Harkhuf returned to Egypt with the products of Punt, such as elephant ivory, incense, and ebony. He also recruited Nubian guards/soldiers, and in the last expedition he recorded bringing back a dwarf, to the great delight of the king.

Provincial cemeteries in the Old Kingdom were not only for high-status elites. At Naga el-Deir, across the river from Bet Khallaf and Reqaqna (see 6.2), George Reisner excavated a number of cemeteries from 1901 to 1904. Tombs of the Old Kingdom were found at 12 locations. The earlier Old Kingdom tombs were mastabas of mud-brick or stone plastered with mud, over burial pits or shafts leading to a roughly cut subterranean chamber(s). The later Old Kingdom tombs in Cemeteries 100-400 were rock-cut, and some also had a rock-cut chapel. The lowest status Old Kingdom burials were simple pit graves. David O’connor has interpreted the large impressive 3rd-Dynasty tombs at Bet Khallaf and Reqaqna as being the burials of royal officials, while the local elite were buried in tombs on the east bank at Naga el-Deir - a pattern which continued in the 4th and 5th Dynasties. Lower-status individuals were also buried at Naga el-Deir in simple graves. To O’Connor these burials suggest a four-tiered social structure in the Thinite region in the early Old Kingdom and at least three tiers later.

In the Faiyum region at Medinet Gurob, British archaeologists Guy Brunton and Reginald Engelbach excavated an Old Kingdom cemetery in 1920. Of the 156 individuals buried there, traces of coffins were found for only seven. Most of the burials were contracted and placed in “shapeless” graves in the loose sand. Brunton and Engelbach remarked about the general poverty of these burials - and even pots were “almost absent.” While the Gurob Old Kingdom burials have been interpreted as low-status ones, they demonstrate the importance of burial ritual for these individuals.

World History

World History