Before Amenhotep IV moved his court to the new capital at Tell el-Amarna in Middle Egypt, he erected four shrines at East Karnak. Although his father Amenhotep III had constructed major temples at Luxor and Karnak, dedicated to the cult of Amen-Ra, his son’s shrines in the Amen temple precinct at Karnak honored the sun-disk deity Aten. The new cult established by Amenhotep IV, who subsequently changed his name to Akhenaten to honor this deity, was later regarded as heresy. Akhenaten’s Karnak monuments were dismantled and blocks of relief from these shrines were used as fill in later constructions at Karnak and Luxor, where they have been found in the course of restoration work in the later 19th and 20th centuries. Decorated with reliefs and inscriptions, thousands of recovered blocks formed a kind of enormous jigsaw puzzle to reconstruct for the Akhenaten Temple Project, directed by Donald Redford (University of Toronto and now Pennsylvania State University).The project included excavations at East Karnak to determine the architectural context of the reliefs from foundation remains. The preserved Karnak talatat blocks have now been cleaned and documented in a database by the ARCE Talatat Project, with data recorded for over 15,500 blocks including details of the reliefs and texts.

Akhenaten’s Karnak reliefs display the early forms of his radically new Atenist religion, which could not have pleased the priests of the nearby Amen cult. Aten is depicted as a sun-disk with rays ending in human hands, which extend the hieroglyph for life (ankh) to the king and his queen Nefertiti (Plate 8.3). With the change in religion, there was also a change in art style. The king is depicted in a bizarrely mannered style, with bloated belly, wide hips, fleshy breasts, and a thin elongated face with large lips and bulbous chin. colossal statues of the king, in the same style and with cartouches carved on his arms and torso (also an innovation), were originally in a court at East Karnak. The shrines were erected quickly, made possible by the innovation of the so-called talatat blocks of sandstone used to decorate the monuments, which were small enough so that one workman could carry one block on his shoulder.

It has been suggested that Akhenaten suffered from a glandular disease which deformed his body, as seen in the early sculpture, but Nefertiti is depicted in the same exaggerated style. Both the king and queen are also known in sculpture of a highly realistic style, including the famous Nefertiti head in Berlin (Plate 8.4). Since Akhenaten’s mummy has not been identified, such a theory cannot be tested on his physical remains, and an art style alone cannot demonstrate a medical problem.

Relief scenes from East Karnak include the king’s sed-festival, which was celebrated quite early in his reign, in Year 2 or 3. The royal couple also perform the ritual of presenting offerings to Aten, while scenes honoring the other important deities are absent. Many temple scenes are of the king and queen in daily life, albeit of a ceremonial nature within the context of temple and palace, such as riding their chariots and making appearances at a special palace window (the “Window of Appearances”). Other reliefs include scenes of workmen building the temple - all of which are a radical departure for temple decoration that would

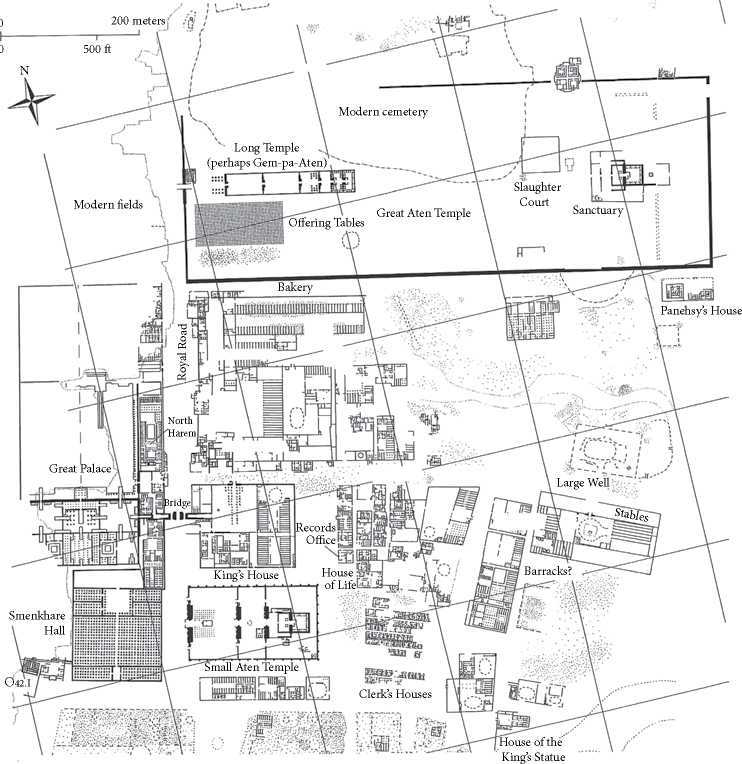

Figure 8.4 Plan of the city of Akhetaten (the site of Tell el-Amarna), including the eastern tombs. Source: illustration by Peter Der Manuelian (after Barry Girsh, in Dorothea Arnold, The Royal Women of Amarna. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996, Figure 13). R. E. Freed, Y. J. Markowitz, and S. H. dAuria (eds.), Pharaohs of the Sun. Akhenaten. Nefertiti. Tutankhamen. Boston: MFA Publications, an imprint of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in association with Bulfinch Press/ Little, Brown, 1999, p. 15. © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Be repeated later at Amarna. The importance of Nefertiti in the Aten cult is clear, and one whole monument at Karnak was devoted to her without Akhenaten.

Akhenaten’s later monuments were located at Akhetaten (Tell el-Amarna), the capital he founded on the east bank in Middle Egypt, which also became the cult center of Aten (Figure 8.4). Given the usually poor preservation of ancient settlements in Egypt, Amarna’s

Figure 8.5 Plan of the central city of Akhetaten. Source: Barry Kemp, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People. London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012, p. 38, Figure 1.10. Reproduced by permission of Barry Kemp.

Remains are exceptional. The site was surveyed in the early 19th century, and Flinders Petrie conducted the first extensive excavations there in the 1890s. From 1901 to 1907 Norman de Garis Davies carefully copied scenes and inscriptions from tombs and boundary stelae. German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt excavated at the site before World War I, which is why the famous head of Nefertiti is in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Since 1977 Barry Kemp has been systematically investigating the site for the Egypt Exploration Society, which also sponsored excavations there after World War I.

The city of Akhetaten, which covered an area of ca. 440 hectares, had no surrounding wall. Although it was a special purpose city, it nonetheless provides an example of Egyptian urban planning (Figure 8.5). The city was organized with a core center planned on a grid, with administrative buildings and residences of different sizes extending southward to the

River Temple. To the north were the North City, North Suburb (with ca. 300 houses), and two palaces. To the east was a walled workmen’s village (with ca. 70 houses), and unfinished rock-cut tombs for high officials were in northern and southern groups in the eastern cliffs. The Royal Tomb was located up a central wadi in the eastern cliffs.

The city was occupied for about 11 years during Akhenaten’s reign, and abandoned by the court early in Tutankhaten/-amen’s reign. Some occupation continued there in the 19th Dynasty, when the Amarna stone temples were dismantled and statues smashed (probably during the reign of Rameses II), but mud-brick buildings were simply left to decay. The site was briefly reoccupied in Roman times, and in coptic times monks lived in some of the northern tombs, one of which became a small church.

The central city contained the largest temple and palace. With an enclosure wall ca. 730 X 229 meters, the Great Aten Temple was entered on the west from the Royal Road. Within this huge enclosure were two main stone structures: the Sanctuary on the east, and the Long Temple to the west. The latter consisted of a columned court and a series of open courts with offering tables and sanctuaries, to the south of which were over 900 open-air offering tables. The Sanctuary has also been reconstructed by Kemp as an open-air temple. Two courts contained numerous small altars, with the temple’s high altar in the second one. The Sanctuary represents a new style of temple architecture, with the innermost room open to the sun, instead of a dark closed sanctuary for the god’s statue. As depicted in Amarna reliefs, Akhenaten and Nefertiti honored Aten at this altar, piled high with food.

To the south of the Great Temple were associated structures, including over 100 baking rooms where many sherds of bread molds were found, as well as the official residence of the high priest and “Keeper of the Cattle of Aten,” Panehesy (where bones of butchered cattle found during the original excavations in 1926 have recently been retrieved from the excavation dump and studied by zooarchaeologist Phillipa Payne). There was also a small private palace (the “King’s House”). According to Kemp, this palace was associated with the largest granaries at Amarna (ca. 2,000 square meters) - suggesting royal and not temple control of basic staples for the king’s officials. A small temple (the “House of Aten”), was possibly some kind of royal mortuary temple, and to the east of this were administrative buildings, including the so-called Records Office, where the Amarna Letters were found (see Box 8-A). Farther east were possible quarters for the military police and stables for horses.

To the west of the Royal Road, which was spanned by a triple-arched bridge, was the Great Palace, much of which has been destroyed by later cultivation. on the east side were rooms of the so-called North and South Harems, a garden court with a pool, and many storerooms. This part of the palace was colorfully painted, including a columned portico with pavement scenes of a papyrus marsh full of birds, with fish swimming in a rectangular pool. The palace had a large courtyard around which were colossal royal statues, and associated buildings, all in stone, probably for special receptions and ceremonies. To the south was an enormous hall with 510 mud-brick columns in 30 rows.

To the south of the central city was a residential area, the Main City, which Kemp characterizes as “a series of joined villages.” House compounds there included that of the sculptor Thutmose, where Nefertiti’s head and other royal sculptures were found. Large circular wells, each with a spiraling ramp, were located throughout this part of the city.

Box 8-A The Amarna Letters

The Amarna Letters were found by peasants at the site of Amarna in 1887, before proper excavations had begun there. unfortunately, a number of tablets were lost before they were recognized for what they are: Egypt’s diplomatic correspondence with the major and minor powers in southwest Asia. Over 380 tablets are known from Amarna, mostly dating to the reign of Akhenaten and coming from a royal archive. But a few tablets are from the latter part of Amenhotep Ill’s reign and possibly the early years of Tutankhamen’s reign.

The letters were written on clay tablets in cuneiform script, and a few also have inked hieratic (Egyptian) notes of scribes recording their receipt at Akhetaten. Cuneiform was used to write a number of different languages in southwest Asia for about 3,000 years. The language in most of the Amarna cuneiform texts is (middle) Babylonian, of a regional form used in the diplomatic correspondence of the ancient Near Eastern powers of the Late Bronze Age.

The letters provide a wealth of information about Egypt’s foreign affairs. Some of the correspondence was with the kings of independent states: Assyria, Babylonia, Hatti (the Hittites), Mitanni (northern Syria), Arzawa (southern coastal Anatolia), and Alashiya (Cyprus). Egypt definitely had the upper hand in these negotiations - of valuable “gifts,” craftsmen, and royal women sent to Egypt, mainly in exchange for Egyptian gold. Letters from the small polities of coastal Syria and Palestine that were under Egyptian control are more about administrative matters, and there are many requests for Egyptian military aid - painting a picture of squabbling self-interest and petty conflicts.

Barry Kemp has suggested that possibly there was a kind of international scribal school in or near the Record Office at Amarna, as suggested by a cuneiform “vocabulary” text on one of these tablets, with Egyptian words written (phonetically) in cuneiform signs in a column on the left and their equivalents in Babylonian on the right. Three fragments of cuneiform tablets have also been found in houses at Amarna - possible evidence of a Near Eastern official in residence at Amarna, or in the case of a tablet with a sign list, an Egyptian learning to read Babylonian.

The letters also provide some information about the increasing success of the Hittites in extending their territory from central Anatolia into northern Syria, at Egypt’s expense. A note can be added on the end of the Amarna Period. A widowed Egyptian queen (probably Tutankhamen’s) wrote a letter to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma stating that there was no king ruling in Egypt. She asked for a Hittite prince to be sent to Egypt so that he could become king. This, of course, would never have been accepted by Egyptian officials and aspirants to the throne. The Hittite prince was assassinated on his way to Egypt, and the last rulers of the 18th Dynasty, Ay (briefly) and (General) Horemheb, were not the descendants of Akhenaten or Tutankhamen.

Large houses were next to small ones, and although there was a hierarchy of house sizes, which suggests a hierarchy of socio-political status at Amarna, there were not exclusive neighborhoods only for high-status families.

Amarna houses were walled mud-brick residences within a brick enclosure wall. The large house of the vizier Nakht had 30 rooms (many of which were only a few square meters in area), but even he, as one of the highest ranking government officials, lived in a significantly smaller dwelling than the palaces of the royal family. A typical large house at Amarna had a small entrance room, a columned reception hall, and a living room with an elevated platform where the owner (and his wife?) sat. This part of the house had a raised ceiling, with windows just below the roof line. There were also private quarters with bedrooms and a bathroom. A staircase led to the roof, which may have been used in warm weather, but the larger houses may have had upper stories. Private shrines with reliefs of Akhenaten and Nefertiti worshipping Aten, sometimes set within a garden, have been found at some Amarna houses.

Barry Kemp has described the basic elements of an Amarna house compound, which included circular grain silos in a court (but some houses also had larger vaulted rooms for grain storage). That grain was stored in private houses indicates some economic independence from the crown, which did not provide sustenance for all the inhabitants at Amarna, and probably private land holdings of such individuals. cooking took place in ovens and hearths outside the house, and animals were kept in sheds. Trees and possibly vegetable gardens were also associated with some houses. Larger houses were also where small-scale production facilities were located, including weaving and potting. Artisan’s workshops could be within the compound or just outside the walls. With no public sewage system, garbage and waste were dumped outside the houses, often near the public wells.

The eastern Workmen’s Village was organized much more rigidly along five north-south streets, with about 70 small houses, including one for an overseer. Unlike the city of Akhetaten, the village was surrounded by a thin wall. Arranged in six blocks, the houses consisted of a hall or court, living room, and two small rear rooms and a back staircase to the roof. upper rooms may have been added by the inhabitants.

The state must have provided water, grain, and basic materials and tools to the workers. Animal pens were located outside the village, where there is evidence of a pig industry. Pigs were butchered and the meat was salted and packed in jars, probably to supplement the villagers’ income. A number of mud-brick chapels, not associated with graves, were also located outside the village and may have been used by families for commemorative rituals. According to Frances Weatherhead, the chapel wall paintings avoided the Amarna style, and other deities were commemorated, including Amen and Isis (whose cults were ignored by Akhenaten). Painted figures of Bes, probably a protective household deity, are also known from houses at Amarna, including the Workmen’s Village (and at Deir el-Medina; see 8.11).

More than 1 kilometer to the southeast of the Workmen’s Village was the Stone Village, with an associated cemetery to the southeast. First located in 1977, the village was excavated beginning in 2005 under the direction of Anna Stevens and Wendy Dolling. Although the stone-walled houses in this village were more informal in plan than those of the Workmen’s Village, the village was probably for a permanent population. The many basalt chips excavated in the village are the debitage from tool making, suggesting that desert-based workers engaged in stone quarrying and/or tomb cutting lived there.

About 2 kilometers to the south of the Stone Village was another cemetery, the South Tombs cemetery, with non-elite burials of the Amarna Period. Studies of the skeletal remains began in 2006 by the Amarna Bioarchaeology Project team (and later field school) from the university of Arkansas. Initial results demonstrate that a large proportion of the humans buried there had short life spans. There is also evidence for childhood nutritional deficiencies and work that involved high risks of injury.

Unlike the geography at Thebes, the elite Amarna tombs were in the cliffs to the east of the city. The Royal Tomb and four unfinished tombs were located farther east in the “Royal Wadi.” Although unfinished and robbed, the royal tomb still had smashed pieces of a sarcophagus in a pillared hall. According to Egyptologist Geoffrey Martin, who studied this tomb, one room may have been intended for Nefertiti’s burial. relief scenes in rooms which open off the tomb stairway include a royal woman’s funeral, perhaps the result of the death of one of Akhenaten’s daughters during childbirth.

Located in two groups to the north and south of the Royal Wadi, most of the Amarna rock-cut tombs were unfinished when the city was abandoned by the court. In the desert near the northern tombs were three so-called desert altars, which Kemp suggests may have been built for some kind of short-term royal celebration.

Many of the reliefs that decorate the Amarna tombs are in poor condition, in part because of the poor quality of limestone in which they were carved. Pre-Amarna Period tombs have relatively few religious scenes and texts, which are missing in the Amarna tombs (with many more in post-Amarna Period tombs). But traditional scenes of the tomb owner, his offices, and his estates, are missing at Amarna. Thus, even in the mortuary cult there were major ideological changes at Amarna. Osirian themes, concerning the most important Egyptian afterlife beliefs, are absent in these tombs. Many tomb scenes focus on the royal family and their activities, especially scenes honoring Aten. Very detailed scenes show the architecture of the palace, Great Temple, and other buildings (as on many talatat blocks) - which has also helped archaeologists to better understand the plans and functions of these buildings. But interpretation of these scenes is not simple because they are not straightforward plans or elevations.

Also found in reliefs from Amarna tombs and other monuments is a change in subject matter. The royal family is frequently depicted in intimate scenes of familiarity. One fragmentary stela even has Nefertiti seated on Akhenaten’s lap, and the king is often shown holding or kissing his small daughters (Figure 8.6). Such scenes are not known before or after the Amarna Period, and seem undignified compared to traditional scenes of the idealized god-king. Possibly Akhenaten had ideological reasons for such depictions of the royal family. Scenes of the army parading along the Royal Road at Akhetaten (and not in battle) are also common. Given the major economic problems that must have arisen when the many gods’ cults (and their priesthoods and temple personnel) were no longer supported, Akhenaten certainly needed the support of the military during his 17-year reign.

Another of the many changes that occurred during the Amarna Period is the use in texts of Late Egyptian, which was the vernacular of the time. For traditional reasons, Middle

Figure 8.6 Fragmented relief of Akhenaten with Nefertiti on his lap holding two princesses. Source: © RMN-Grand Palais (Musee du Louvre)/Franck Raux.

Egyptian, which was no longer the spoken language, continued to be used in official and religious texts, but Amarna texts are written in a form of Late Egyptian. The “Hymn to Aten,” which is found inscribed in Amarna tombs, describes an omnipotent and universal god, the creator of all living things - which is also depicted in a lively and naturalistic style in reliefs from Karnak. A number of images in this hymn are paralleled in the 104th Psalm in the Old Testament.

Akhenaten has sometimes been called the world’s first monotheist, and even Sigmund Freud wrote a book about this: Moses and Monotheism. But Akhenaten’s religion had a dual aspect: the celestial Aten, and the worship of the god through his son Akhenaten (and Nefertiti). Thus, there was a certain remoteness to the sun-disk Aten, who unlike other Egyptian gods was not depicted in an anthropomorphized image. As noted above, the changes that occurred were cultural, not only religious, and the reforms were of such an all-encompassing nature that they probably emanated directly from Akhenaten.

The Amarna Period is a fascinating though brief time that produced extraordinarily beautiful art and decoration - and a royal capital that has been extensively investigated by archaeologists. It is both ironic and fortuitous that because of so much intentional dismantling and reuse of stone from Akhenaten’s monuments a great deal of information about this unique period has been preserved.

World History

World History