A large and constantly expanding literature addresses and debates the technical characteristics of ship form and construction in the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean. (General overviews can be found in Basch 1987; Mark 2005; McGrail 2001; Wachsmann 1998; Wedde 2000.) During the Bronze Age, images of ships were painted onto pottery and wall frescoes and incised, engraved, embossed, and impressed onto pottery, stone, seals and sealings, and metal jewelry. A surprising fact is that Aegean Bronze Age civilizations, ostensibly linked so closely with the sea, depicted watercraft so infrequently. A recent catalogue of ship representations from the Aegean Bronze Age counts approximately 80 painted ship images from sherds or whole vessels; more than 20 on the painted wall frescoes from the West House at Akrotiri on the island of Thera and a few others from fragmentary frescoes at Pylos, Iklaina, and Mycenae; 138 from seals and sealings; 43 incised, impressed, engraved, or embossed on ceramic, stone, or metal objects; nearly 50 watercraft models; and a further 26 as Cretan hieroglyphic or Linear A signs (Wedde 2000). In all then, we have fewer than 400 surviving images of ships for a period of 2,000 years.

Inferences about the ships depicted in iconographic representations are often controversial because there is no consistent artistic convention. Bronze Age artists did not necessarily attempt or achieve faithful reproductions of the details of actual ships. This discrepancy may have resulted from deliberate stylization and abstraction (innovation), imitation of contemporary examples of ship iconography, or the use of a pattern book of ship icons. Often, the medium severely limited the amount of accurate detail that could be rendered: the miniscule working surface of seals necessitated executing many details in abbreviated, schematic form, and leaving others out altogether. Two-dimensional representations on any medium make it difficult to estimate a ship's beam or to interpret features such as appendages to the decks, bows, or sterns. Even in the larger formats of frescoes and pottery surfaces, details may be represented in ambiguous or stylized fashion, leaving modern scholars to speculate on the meaning of painted lines and other flourishes. These contingencies can make it difficult to reconstruct a typology of vessel types or to identify regional variability in ship construction.

A particular frustration is that within this limited corpus, virtually nothing is known about small boats of the kind that should have formed the backbone of short-distance maritime connectivity. Such small craft stand little chance of preservation as shipwrecks except in the kinds of contexts — peaty or waterlogged deposits, for example — that are rare in the Aegean. In the absence of hull remains, wrecks of small vessels, with their diminutive cargoes, are unlikely to be recognized as such by even the most fine-grained underwater surveys. Certain boat models and seals are thought to represent small craft, though scale is difficult to infer from them, and in general artists apparently preferred to depict the more impressive galleys and trading ships of the time. For this reason, the “Flotilla Fresco" from Akrotiri on the Cycladic island of Thera takes on a disproportionate significance in understanding Bronze Age Aegean small craft. The fresco's narrative scene shows a full range of vessel types, including several small canoe-like boats and other vessels of modest size, propelled by paddles, oars, and sails.

The Flotilla Fresco

The so-called Flotilla Fresco was part of a frieze that adorned the upper walls of Room 5 in the West House at Akrotiri on Thera. It occupied the southeastern corner of the east wall and the south wall of the small, 4 x 4 meter room (Warren 1979: 117, fig. 1). Opposite on the north wall, scenes of a shipwreck or sea battle are depicted, along with marching soldiers. The flotilla scene shows a procession of ships of various kinds, apparently leaving one coastal settlement (the “Departure Town") and arriving at the harbor of a second (the “Arrival Town"; Fig. 2.6). The second town is built above a double harbor formed by a larger and a smaller embayment divided by a narrow promontory. In both towns, spectators gather near the shore and in houses upslope amidst an atmosphere of excitement. The flotilla is composed of seven large sailing ships, highly ornamented with decorative elements, ikria (stern cabins), and awning

2.6 The Flotilla Fresco, West House Room 5, Akrotiri. Doumas 1992: 68, fig. 35. Courtesy of the Thera Foundation - Petrikos M. Nomikos.

Structures amidships under which well-dressed individuals sit. Only one of the ships is moving under sail, however. The rest are being paddled awkwardly by men straining to reach the water line. Seven other boats are part of the scene: one medium-sized boat is being rowed out of the Departure Town; two small boats with awning structures are moored in the larger of the harbors at the Arrival Town; three small canoes are drawn up on the beach of the smaller harbor of the Arrival Town; and one canoe is being rowed out to meet the arriving flotilla, perhaps to act as a pilot guiding the large ships to safe anchorage.

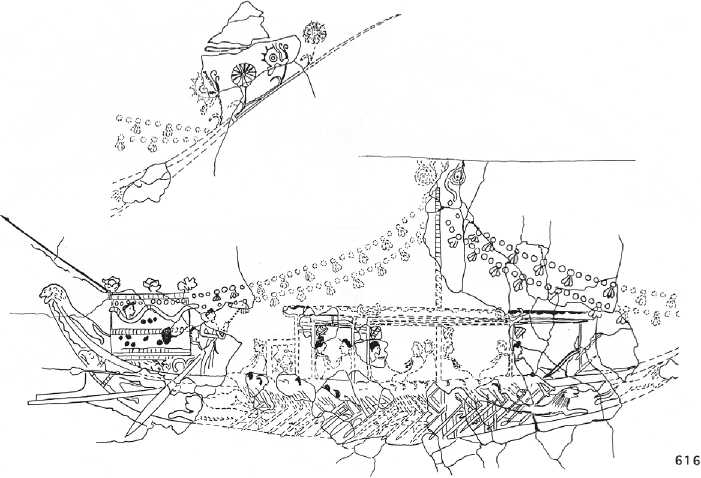

An interpretation of the scene as representing a ceremonial procession of some type is persuasive for many reasons (Marinatos 1974a; Morgan Brown 1978; Strasser 2010; Warren 1979). Most notable are the unusual circumstances of the ships and their occupants, which suggest that this could not be a routine military or commercial exercise. The large ships are all decorated at the prow and stern, and some have hulls painted with figural motifs or abstract designs. The most elaborate (Spyros Marinatos' “flagship") has a hull decorated with lions and dolphins, and a tall mast from which dress-ship lines festooned with crocus-bloom pendants run to the prow and stern (Fig. 2.7). The fact that six of the seven ships are being paddled is curious, because by LH I this archaic means of propulsion would have long been abandoned in favor of oar and sail, particularly for ships of this size as the paddlers' exertions attest. The other installations aboard the ships are similarly out of the ordinary, if not so quaint. The ikria are small stern cabins consisting of a framework of wooden posts hung with a screen of oxhide or woven fabric (Shaw 1980, 1982; Wedde 2000: 132-34), where the shipmaster or an honored guest might sit. Ikria are also found as large-scale fresco motifs in Room 4 of the West House, and at Mycenae (Shaw 1980, 1982). Awning structures cover seated passengers who take no part in paddling the ship; boar's tusk helmets suspended from the roof of some awnings indicate that the passengers are soldiers. Their decorative tunics, stiff-looking and hiding their limbs, resemble the costume later worn by elite chariot passengers depicted on pictorial kraters of the thirteenth century BC. The ikria and awnings would have been a great hindrance to the efficient conduct of military or commercial business; it is believed that they were detachable structures that could be assembled for special occasions and then disassembled easily (Morgan 1988: 139; Shaw 1982: 55). The nature of the ceremony is a matter of speculation, but two of the more plausible suggestions are a nautical festival celebrating the inauguration of a new sailing season in spring (Morgan 1988: 143—45; Morgan Brown 1978), and a cultic procession commemorating the third-millennium Cycladic longboats (Wachsmann 1998: 108—113), which were sufficiently impressive and symbolically charged for their time to have lived long in memory. Because there is only one ship under sail, the ceremony might even reenact the introduction of the sailing ship to Crete toward 2000 BC.

The Flotilla Fresco is the single most important visual document of the Late Bronze Age for coming to terms with Aegean seafaring. It shows a range of ships and boats with sufficient realism that we can ascertain details about their form and construction, rigging and sails, methods of propulsion, and possible functions, in spite of the ceremonial modifications. The coastal scene also confirms some basic features of Bronze Age seafaring. The Arrival Town's double harbor, formed by a narrow headland with flanking embayments, was a preferred harbor topography in the Bronze Age. These are clearly natural harbors, as no durable harbor constructions are visible; instead three small canoes are pulled up onto the sandy beach of the smaller harbor, while two medium-sized vessels appear to be anchored in the middle of the larger harbor. The larger harbor may have a deeper approach suitable for bigger seacraft. The Minoans did have one kind of dedicated harbor structure, the ship shed, located some distance from the shore and used for storage of ships and nautical equipment during the winter months (see Chapter 5). A portion of the fresco on the north wall of West House Room 5 depicts soldiers marching to the right of a large building partitioned into narrow, open galleries facing the shore, very similar in form to Building P at Kommos, the best known archaeological example of a ship shed. Building P is dated to the later fourteenth century BC, some two centuries or more later than the Flotilla Fresco, but another putative ship shed at Gournia may have been built in MM IIIA (Watrous 2010), earlier than the Flotilla Fresco and indicating a long tradition into which the example at Akrotiri fits comfortably.

A detailed discussion of the watercraft depicted in the Flotilla Fresco is presented in Chapter 3, and further comment on the harbor setting is made

2.7 "Flagship" from the Flotilla Fresco, Akrotiri. Wedde 2000: Catalogue 616. Courtesy of Michael Wedde.

In Chapter 4. The main limitation of the Flotilla Fresco for our purposes is the chronological gap between the massive eruption that destroyed Akrotiri and the earliest verifiable representations of Mycenaean ships and boats. The debate over the date of the eruption is as contentious as ever (see recently the papers in Warburton 2009), but whether it occurred in the later seventeenth century or sometime in the sixteenth, the connection between the ships and boats of the Flotilla Fresco and the earliest ships represented in Mycenaean art in the later fourteenth century (LH IIIA2) would seem tenuous, but recent revelations of ship frescoes at Pylos and Iklaina may help to clarify the evolution of ship technology during the intervening period (Chapter 3).

Portrayals of Mycenaeans abroad are rare, and they seem only to be recognizable as soldiers wearing boar's tusk helmets. In addition to the Amarna papyrus, there is a warrior, possibly wearing a boar's tusk helmet, painted onto a sherd found at Hattusa and dated to circa 1400 BC (Niemeier 2003: 105, fig. 4). Mycenaeans were not among those painted on tomb walls in Egypt, as were the Cretans before them. Nor do any of the Aegean-style painted frescoes from the East — at Tel Kabri in Israel, Alalakh and Qatna in Syria, and Tell el-Dab'a in Egypt — appear to have Mycenaean connections (Cline et al. 2011).

Pottery and Other Media

Continuing on the theme of the relationship between the Minoan/Cycladic and the Mycenaean seafaring traditions, illustrations of distinctly Mycenaean ships on pottery and other media are curiously late. The Mycenaean oared galley, which may have been an entirely new design (Wedde 2005: 29), is first portrayed on pottery in LH IIIB, but not in great numbers, and other types of craft are generally not depicted at all. Surprisingly, images of the galley on pottery increase after the collapse of the palaces in LH IIIC, a pattern that has social and artistic dimensions that are explored in Chapter 3. Ship images on pottery are subject to all of the ambiguities of artistic representation, with the additional challenge of working on a curved surface.

Boat models in clay are the only three-dimensional representations of Bronze Age watercraft (Fig. 2.8). Models help give a sense of the beam, as well as features such as keels (either painted, or represented three-dimensionally as swellings or protrusions in the clay) and thwarts. Some surely represent small boats rather than the larger ships that predominate in all other media, but their typically crude execution makes determination of dimensions speculative. Of the approximately 50 whole or fragmentary boat models, more than 20 have been found on the mainland, and these range in date from LH IIIA to LH IIIC (Wedde 2000: 307—312). EBA boat models come from Crete and the Cyclades; during the MBA they are limited to Crete; and in the LBA they are found on Crete, in the Cyclades, and on the mainland. Most of the boat models survive as fragments only, limiting the amount of useful information that can be extracted from them.

Seals and sealings with ship imagery come almost exclusively from Crete, where the corpus numbers more than 125, with increasing frequency through the Bronze Age until the destruction of the neopalatial palaces at the end of LM IB (Wedde 2000: 331—49). Fewer than ten have been found on the mainland, in contexts ranging from EH III/MH I to LH IIIB. These undoubtedly represent sporadic arrivals from Crete. As mentioned above, realistic details are difficult to render on such small surfaces, and to make matters more challenging there is a large subclass, the so-called talismanic seals, with particularly abstract designs (Wedde 2000: 134-41).

World History

World History