During the early 1800s, the movement across the top of the country gained momentum and an initial lead over migration from the southern states (see Table 8.1 on page 134 and Map 8.3 on page 136). During the first quarter of the century, people from the New England and Middle Atlantic states were pouring into the northern counties of Ohio and Indiana and later into southern Michigan. By 1850, lower Michigan was fairly well settled,

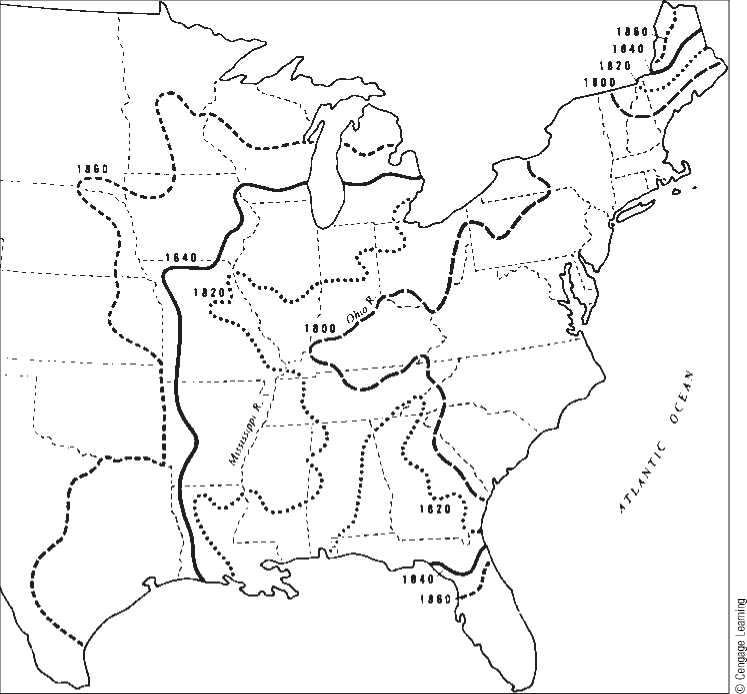

MAP 8.3

Moving Frontier

Census data from 1800 onward chronicled the constant westward flow of population. The “frontier,” its profile determined by natural attractions and a few man-made and physiographic obstacles, was a magnet for the venturesome.

And the best lands in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin had been claimed. On the eve of the Civil War, pioneers were pushing the northwestern tip of the frontier into 1810 central Minnesota, most of Iowa was behind the frontier line, and the handsome country of eastern Kansas was being settled. Only in Texas did the frontier line of 1860 bulge farther to the west than it did in Kansas. By this time, California had been a state for a decade and Oregon had just been admitted, but the vast area between the western frontier and the coast was not to be completely settled for another half-century.

Southerners moving across the Ohio River were the chief influence in the lower part of the old Northwest. New Englanders, after the Erie Canal made transportation easier, were dominant in the Great Lakes region, but they were joined by another stream that originated in the Middle Atlantic states. For the most part, families moved singly, although sometimes as many as 50 to 100 would move together. As the frontier pushed westward, the pioneers on the cutting edge were frequently the same people who had broken virgin soil a short way back only a few years before. Others were the grown children of men and women who had once participated in the conquest of the wilderness.

Throughout this early period of westward expansion was an ever-increasing influx of land-hungry people from abroad. From 1789 to the close of the War of 1812, not more than a quarter million people emigrated from Europe. With the final defeat of Napoleon and the coming of peace abroad, immigration resumed. From half a million people in the 1830s, the flow increased to 1.5 million in the 1840s and to 2.5 million in the 1850s. For the most part, the newcomers were from northern Europe; Germans and Irish predominated, but many immigrants also came from England, Scotland, Switzerland, and the Scandinavian countries. Of these peoples, the Germans tended more than any

In the nineteenth century, wagon trains brought a steady stream of migrants to western America and its expansive lands.

Others to go directly to the lands of the West. Some immigrants from the other groups entered into the agricultural migration, but most were absorbed into eastern city populations. The timing of the western migration is discussed in Economic Insight 8.1.

MIGRATION WAVES AND ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY

Is there an economic explanation to the timing of the western migrations? Although the absolute numbers of western migrants from the eastern states and from abroad continued to swell, the decades of greatest western expansion, in terms of percentages, were the 1810s and 1830s. In absolute terms, the 1850s were the greatest. From Table 8.1 (see page 134, we can calculate percentage rates of increase of the western population for the five decades from 1810 to 1860: These were 6.9, 4.9, 5.6, 4.2, and 4.1 percent. Also from Table 8.1, we see the greatest increase in absolute numbers coming in the 1850s: nearly 4.3 million people.

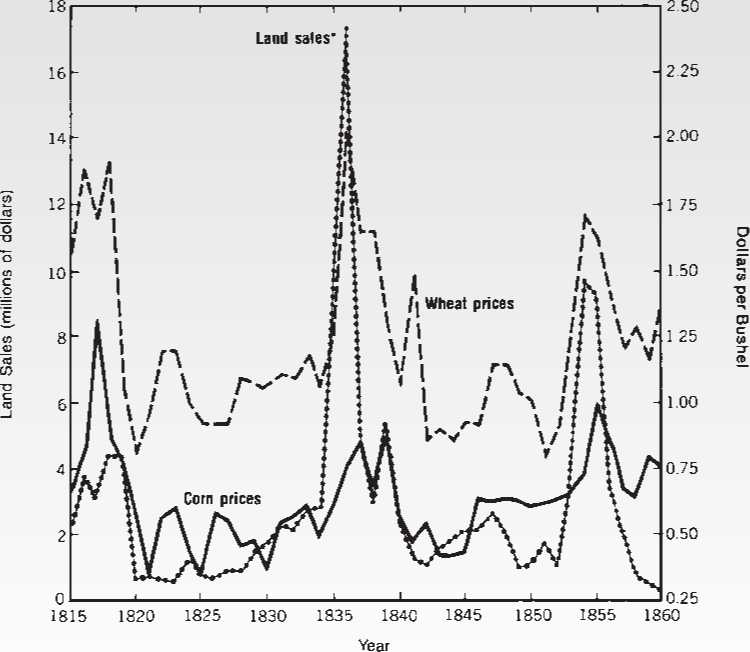

As Douglass C. North has argued, in large measure, these surges are explained by the exceptional economic opportunities in the West (North 1961). Hogs, corn, and wheat became the great northwestern staples, and as shown in Figure 8.2, page 138, corn and wheat prices were unusually high in these decades. People came to the new lands in response to the profits to be made in the production of these important products.

Critics of North’s “market opportunity response” argument have countered that land sales during these periods were based on pervasive speculation, not settlement and production for market (see, for example, Martin 1972; Temin 1969). Much of the land, however, was being put to use. The decades of greatest growth in “improved land” (for grazing, grass, tillage, or lying fallow) were also the 1810s, 1830s, and 1850s. The percentage rates of change in improved acres from 1810 to 1860, by decade, were 23.5, 6.5,7.1, 5.4, and 7.8 (Haites, Mak, and Walton 1975,113). In short, North’s critics were wrong.

The only variable slightly out of step with North’s general argument is the western population growth rate for the 1850s. This slowdown would be expected, however, from the general slowing of growth for the total population, the rise in the number of improved acres per person, and the rise in agricultural productivity— all of which occurred. The supply response to high staple prices is observed in terms of both population and improved acres in the 1810s and 1830s, but the supply response to the boom years of the 1850s was dominated more by improved acres than by population.

MIGRATION WAVES AND ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY, Continued

FIGURE 8.2

U. S. Public Land Sales in Several Western States* and Wheat and Corn Prices, 1815-1860

Source: North 1961, 137.

*Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Missouri.

World History

World History