Russia underwent two revolutions during 1917. The first, in February, eliminated the Tsar’s aristocratic rule. In its place, a reformist provisional government was set up. This compromise did not satisfy the radical

Bolshevik party, which favored a Marxist revolution to bring the worker and peasant classes to power. When the provisional government failed to halt Russia’s hopeless and unpopular struggle against Germany in World War I, the Bolshevik cause gained support, especially from the military. In October, Vladimir Lenin led a second revolution that created the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

The February Revolution had relatively little effect on the Russian film industry, which had expanded during the war. Films made just prior to the revolution appeared, and a few films with political subject matter were rushed through production. Evgenii Bauer, a leading prerevolutionary director, made The Revolutionary, released in April; it supported Russia’s continued participation in World War I. Yakov Protazanov’s Father Sergius, produced between the two revolutions, was released in 1918. This film carried on the tradition of the mid-1910s Russian cinema, with its emphasis on psychological melodrama (see pp. 60-62).

The Bolshevik Revolution in October created a far greater disruption in Russian life in general. Given that the Communists favored state ownership of all companies, existing film firms waited nervously to see what would happen. Coincidentally, Bauer died in the spring of 1917, and the illness of his producer, Alexander Khanzhonkov, ended that company’s existence. Another major prerevolutionary producer, Alexander Drankov, left the USSR in the summer of 1918 and tried vainly to reestablish his business abroad. After a brief trial period of producing propaganda films commissioned by the new government, the Yermoliev troupe fled to Paris via the Crimea in 1919; there they established a successful company, Films Albatros (p. 90).

The logical first step for the new Marxist regime would have been for the government to acquire, or nationalize, the film industry. The Bolsheviks, however, were not yet powerful enough for this step. Instead, a new regulatory body, the People’s Commissariat of Education (generally known as Narkompros), was assigned to oversee the cinema. The commissar, or head, of Narkompros was Anatoli Lunacharsky. He was interested in film and occasionally wrote scripts. Lunacharsky’s sympathetic attitude later helped create favorable conditions for the Montage directors.

During the first half of 1918, Narkompros struggled to gain control over film production, distribution, and exhibition. A few Soviets, or local workers’ governing bodies, set up their own production units, making propaganda films promoting the new society. For example, the Petrograd Cinema Committee produced Cohab-

6.1 Cohabitation ends with documentary shots of cheerful revolutionary soldiers, giving this rather crudely made early Soviet film an air of historical immediacy.

Itation (1918), made by a collective of directors and scripted by Lunacharsky. Under Soviet rule, large houses that had previously belonged to rich families were divided to provide dwellings for poorer families. In Cohabitation, a well-to-do professor and a poor janitor work at the same school; when the janitor and his daughter are assigned to live in the professor’s large home, the latter’s wife objects. Eventually all learn to live together in harmony (6.1).

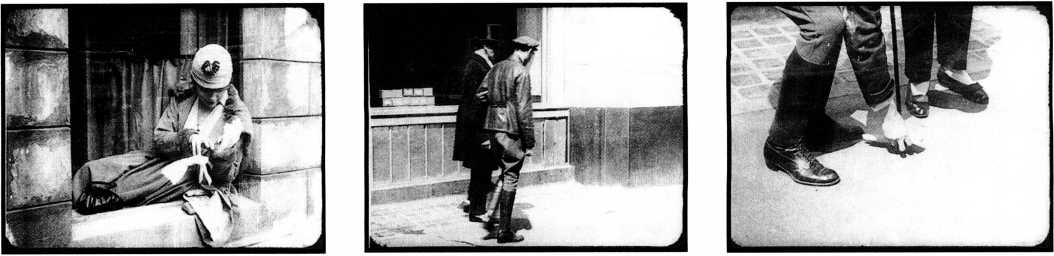

The year 1918 also saw the first directorial efforts of two young men who were to become major directors in the 1920s. In June, Dziga Vertov took charge of Narkompros’s first newsreel; later he would be an important documentarist working in the Montage movement. Before the October Revolution, Lev Kuleshov made Engineer Prite’s Project (released 1918) for the Khanzhonkov firm, where he had previously worked as a set designer. Only a few scenes from the film survive, but they indicate that, unlike his contemporaries in Russia, Kuleshov employed Hollywood-style continuity guidelines (6.2-6.6). Kuleshov’s later teachings and writings explored the implications of Hollywood continuity style in detail.

Despite these tentative signs of progress, however, Soviet production received two serious blows during 1918. Because the companies that had fled after the revolution had taken whatever they could with them, the USSR badly needed production equipment and raw stock. (Neither was manufactured there.) In May, the government entrusted $1 million in credit to a film distributor who had operated in Russia during World War I, Jacques Cibrario. On a buying mission to the United States, Cibrario purchased worthless used material and absconded with most of the money. Russia had little foreign currency, and the loss was serious. It is little wonder that the government was reluctant to give the film industry further large sums. Another problem arose in June 1918, when a decree required that all raw stock held by private firms be registered with the government. The

6.2 A scene in Engineer Prite’s Project uses continuity editing, as a woman seated at a window drops something to attract the attention of two men passing below.

6.3 A long shot shows them noticing the object.

6.4 In a cut-in, the hero picks it up.

6.5 In another shot, he looks up and right.

6.6 In the reverse shot, the woman looks back at him. The rest of the scene proceeds in standard continuity fashion.

Remaining producers and dealers promptly hid what little raw film remained, and a severe shortage developed.

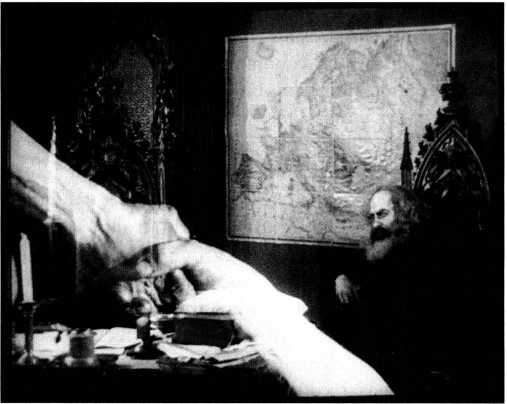

From 1918 to 1920, Soviet production, distribution, and exhibition were disorganized. Production remained low at first. Only six films were produced under state auspices in 1918. Sixty-three were made in 1919, but most of these were short newsreels and agitki, brief propaganda films with simple pro-Soviet messages. Workers of All Lands, Unite! (1919), for example, showed scenes from the history of the struggle of workers across the ages, linked by quotes from Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto (6.7). Conditions remained bleak, however, especially for the few private firms still producing films. When the Russ company set out in 1919 to adapt Tolstoy’s Polikushka, lack of food, heat, and positive film stock created incredible difficulties. The film did not reach theaters until late 1922.

These were the years of the civil war in the USSR, as the Reds, or Bolshevik forces, fought the Whites, Russians opposed to the revolutionary government and supported by Britain, the United States, and other countries. In 1920, the Bolsheviks won, but at a terrible cost.

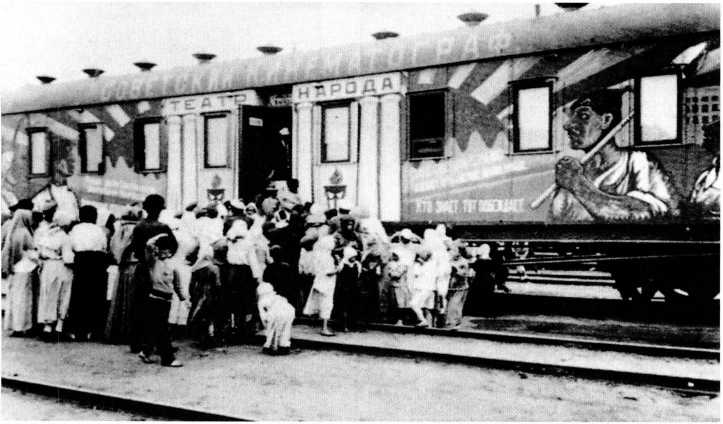

During the civil war, a major concern was to get films out to troops and villagers in the countryside. Many of

6.7 An actor playing Karl Marx sits before a map of Europe, writing the Communist Manifesto. The superimposed clasping workers’ hands symbolize his inspiration for the famous command (and the film’s tide) Workers of All Lands, Unite!

6.8, A decorated agit-train called the “V. I. Lenin.” The sign at the top reads “Soviet Cinematograph,” indicating that the train carried a projection setup.

The far-flung areas had no movie theaters, and the Soviet government innovated the use of agit-vehicles. Trains, trucks, even steamboats (6.8) visited the countryside. Painted with slogans and caricatures, they carried propaganda leaflets, printing presses, even small filmmaking setups. They put on theatrical skits or showed movies on an outdoor screen for local crowds.

Production, however, continued at a low level. In August 1919, Lenin finally nationalized the film industry. The main effect of this move was the discovery of many old films—both Russian and foreign—that had been stored away. These films provided most of what Soviet citizens saw in theaters until 1922.

The departure of the Yermoliev and Drankov companies, along with the dissolution of Khanzhonkov, meant that a generation of Russian filmmakers had largely disappeared. Who would replace them? Despite the hardships of War Communism, Narkompros established the State Film School in 1919. In 1920, the young director of Engineer Prite’s Project, Lev Kuleshov, joined the faculty and formed a small workshop that was to train some of the era’s important directors and actors.

Over the next few years, working under conditions of great deprivation and often without film stock for their experiments, Kuleshov’s group explored the new art. They practiced acting and put on plays and skits staged as much like films as possible. Some of the skits used small frames with curtains, within which the actors stood to create “close-ups.” Later they experimented with film scenes, reediting old films. In 1921, Kuleshov obtained a small amount of precious raw stock from the government and shot what are known as the “Kuleshov experiments.” In all of these, the group explored an editing principle now called the Kuleshov effect.

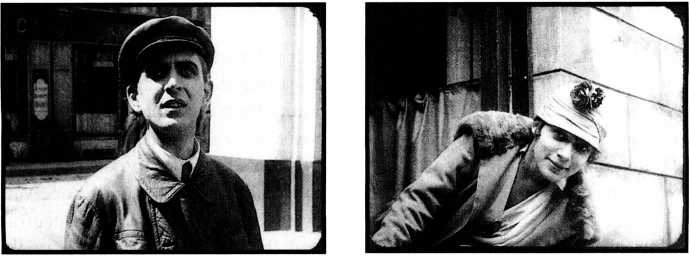

The Kuleshov effect is based on leaving out a scene’s establishing shot and leading the spectator to infer spatial or temporal continuity from the shots of separate elements. Often Kuleshov’s experiments relied on the eyeline match. The workshop’s most famous experiment involved recutting old footage with the actor Ivan Mozhukhin. A close view of Mozhukhin with a neutral expression was selected. This same shot was repeatedly edited together with shots of other subject matter, variously reported as a bowl of soup, a dead body, a baby, and the like. Supposedly, ordinary viewers praised Mozhukhin’s performance, believing that his face had registered the appropriate hunger, sorrow, or delight— even though his face was the same each time they had seen it. This Mozhukhin experiment does not survive, unfortunately, but two other Kuleshov experiments were rediscovered during the 1990s. One stages a fight on a balcony, watched by a man on a sidewalk nearby. Its skillful editing, especially with its use of eyeline matching, reflects the knowledge of continuity style that Kuleshov had demonstrated in Engineer Prite’s Project (see 6.2-6.6). A second, poetically called The Created Surface of the Earth, assembled a unified space out of shots made in various widely separated locations, all united by the eyeline matches between a man and a woman who meet in a park. Unfortunately the ending is missing, but it showed the pair looking and pointing offscreen (6.9), followed by a shot of the U. S. Capitol (taken from an old film), and finally shots of the pair walking along a Moscow street ascending a flight of steps—which the editing suggests are those of the Capitol but which were actually filmed at a cathedral in Moscow. In all of the Kuleshov experiments, the filmmakers built up an overall space that had not existed during filming.

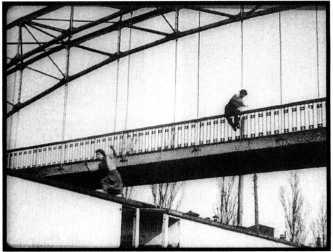

6.10 In scenes like this, when the children leap from a bridge onto a train during the defense of their town, Red Imps captured the fast pace of American adventure films of the 1910s.

6.9, Actors in a Moscow park look and point offscreen. The next shot (missing) showed the U. S. Capitol, which they seem to see.

The major implication of Kuleshov’s experiments was that in cinema the viewer’s response depended less on the individual shot than on the editing—the montage of the shots. This idea was to be central to the Montage filmmakers’ theory and style. The move from classroom experimentation to film production would be difficult for Kuleshov’s group, however, for the Soviet film industry’s construction took several years.

World History

World History