What were the different approaches to the Reconstruction of the Confederate states?

How did white southerners respond to the end of the old order in the South?

To what extent did blacks function as citizens in the reconstructed South?

What were the main issues in national politics in the 1870s?

!t;

Why did Reconstruction end in 1877?

I

N the spring of 1865, the Civil War was finally over. At a frightful cost of 620,000 lives and the destruction of the southern economy and much of its landscape, the Union had emerged triumphant, and some 4 million enslaved Americans had seized their freedom. The ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865 abolished slavery everywhere. Now the nation faced the daunting task of reuniting. A civil war fought by the North to save the Union had become a transforming social force. The abolition of slavery, the war-related disruptions to the economy, and the horrifying human losses suffered during the war had destroyed the plantation system and upended racial relations in the South. The defeated Confederacy now had to come to terms with a new order as the United States set about “reconstructing” a ravaged and often resentful South. The era of Reconstruction, from 1865 to 1877, was a period of political complexity and social turbulence that generated far-reaching implications for American life. It witnessed a prolonged debate about issues of enduring significance, questions about the nature of freedom, equality, and opportunity.

By far the most important of those questions was the fate of African Americans. The Union could not have been saved without the help of the blacks, but what would be their status in the postwar era?

The War’s Aftermath

In the war’s aftermath the victors confronted difficult questions: How should the United States be reunited? What was the status of the states that had seceded? Should the Confederate leaders be tried for treason? Should former Confederates automatically have their U. S. citizenship restored? How should new governments be formed in the South? How and at whose expense was the South’s economy to be rebuilt? Should debts incurred by the Confederate state governments be honored? Who should pay to rebuild the South’s railroads and public buildings, dredge the clogged southern harbors, and restore damaged levees? What was to be done for the freed slaves? Were they to be given land? social equality? education? voting rights?

Such complex questions required sober reflection and careful planning, but policy makers did not have the luxury of time or the benefit of consensus. Some northerners wanted the former Confederate states returned to the Union with little or no changes in the region’s social, political, and economic life. Others wanted southern society punished and transformed. The editors of the nation’s foremost magazine, Harper’s Weekly, expressed this vengeful attitude when they declared at the end of 1865 that “the forgive-and-forget policy. . . is mere political insanity and suicide.” development in the north To some Americans the Civil War had been more truly a social revolution than the War of Independence, for it reduced the once-dominant influence of the South’s planter elite in national politics and elevated the power of the northern “captains of industry.” During and after the Civil War, the U. S. government grew increasingly aligned with the interests of corporate leaders. The wartime Republican Congress had delivered on the party’s major platform promises of 1860. In the absence of southern members, the Congress had centralized national power and enacted the Republican economic agenda. It passed the Morrill Tariff, which doubled the average level of import duties. The National Banking Act created a uniform system of banking and bank-note currency and helped finance the war. Congress also decided that the first transcontinental railroad would run along a north-central route, from Omaha, Nebraska, to

Sacramento, California, and it donated public land and sold bonds to ensure its financing. In the Homestead Act of 1862, moreover, Congress provided free federal homesteads of 160 acres to settlers, who had only to occupy the land for five years to gain title. No cash was needed. The Morrill Land Grant Act of the same year conveyed to each state 30,000 acres of federal land per member of Congress from the state. The sale of some of the land provided funds to create colleges of “agriculture and mechanic arts.” Such measures helped stimulate the North’s economy in the years after the Civil War.

DEVASTATION IN THE SOUTH The postwar South offered a sharp contrast to the victorious North. Throughout the South, property values had collapsed. Confederate bonds and paper money were worthless; most railroads were damaged or destroyed. Cotton that had escaped destruction was seized by federal troops. Emancipation wiped out $4 billion invested in human flesh and left the labor system in disarray. The great age of expansion in the cotton market was over. Not until 1879 would the cotton crop again equal the record harvest of 1860; tobacco production did not regain its prewar level until 1880; the sugar crop of Louisiana did not recover until 1893; and the old rice industry along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia never regained its prewar levels of production or profit.

A street in the “burned district”

Ruins of Richmond, Virginia, in the spring of 1865.

For many southerners, the emotional devastation caused by the war was worse than the physical destruction. Many families had lost sons and husbands; other war veterans returned with one or more limbs missing. Few families were untouched by the war, and most Confederates resented the humiliation of military occupation. The scars felt by a war-damaged, land-proud South would take time to heal, a very long time.

A TRANSFORMED SOUTH The defeat of the Confederacy transformed much of southern society. The freeing of slaves, the destruction of property, and the collapse of land values left many planters destitute and homeless. Amanda Worthington, a planter’s wife from Mississippi, saw her whole world destroyed. In the fall of 1865, she assessed the damage: “None of us can realize that we are no longer wealthy—yet thanks to the Yankees, the cause of all unhappiness, such is the case.” Union soldiers who fanned out across the defeated South to impose order were cursed and spat upon. Fervent southern nationalists, both men and women, implanted in their children a hatred of Yankees and a defiance of northern rule.

LEGALLY FREE, SOCIALLY BOUND In the former Confederate states, the newly freed slaves often suffered most of all. They were no longer slaves, but were they citizens? After all, the U. S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision (1858) had declared that enslaved Africans and their descendants were not eligible for citizenship. Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 implied that former slaves would become U. S. citizens, but citizenship was then defined and protected by state law, and the southern states in 1865 did not have state governments. The process of forming new state governments required first deciding the official status of the seceded states: Were they now conquered territories? If so, then the Congress had the authority to recreate their state governments. But what if it were decided, as Lincoln argued, that the former Confederate states had never officially left the Union because the act of secession was itself illegal? In that circumstance, the process of re-forming state governments would fall within the jurisdiction of the executive branch and the citizens of the states.

Adding to the political confusion was the need to help the former slaves, most of whom had no land, no home, and no food. A few northerners argued that what the ex-slaves needed most was their own land. In coastal South Carolina and in Mississippi, former slaves had been “given” land by Union armies after they had taken control of Confederate areas during the war. But such transfers of white-owned property to former slaves were reversed during 1865. Even northern abolitionists balked at proposals to confiscate white-owned land and distribute it to the freed slaves. Citizenship and legal rights were one thing, wholesale confiscation of property and land redistribution quite another. Instead of land or material help, the freed slaves more often got advice about proper behavior.

THE FREEDMEN’s BUREAU It fell to the federal government to address the desperate plight of the former slaves. On March 3, 1865, while the war was still raging, congress created within the War Department the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands to provide “such issues of provisions, clothing, and fuel” as might be needed to relieve “destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children.” It was the first federal experiment in social welfare, albeit temporary. In May 1865, General Oliver O. Howard, commissioner of what came to be called the Freedmen’s Bureau, declared that freed slaves “must be free to choose their own employers, and be paid for their labor.” He sent Freedmen’s Bureau agents to the South to negotiate labor contracts (something new for both blacks and white planters), provide medical care, distribute food, and set up schools. The bureau organized its own courts to deal with labor disputes and land titles, and its agents were authorized to supervise trials involving blacks in other courts.

The intensity of racial prejudice in the South often thwarted the efforts of Freedmen’s Bureau agents—as well as federal troops—to protect and assist the former slaves. In late June 1865, for example, a white planter in the low country of South Carolina, near Charleston, signed a contract with sixty-five of his former slaves calling for them to “attend & cultivate” his fields “according to the usual system of planting rice & provision lands, and to conform to all reasonable rules & regulations as may be prescribed” by the white owner. In exchange, the workers would receive “half of the crop raised after having deducted the seed of rice, corn, peas & potatoes.” Any workers who violated the terms of the contract could be evicted from the plantation, leaving them jobless and homeless. A federal army officer who witnessed the contract reported that he expected “more trouble on this place than any other on the river.” Another officer objected to the contract’s provision that the owner could require workers to cut wood or dig ditches without compensation. But most worrisome was that the contract essentially enslaved the workers because no matter “how much they are abused, they cannot leave without permission of the owner.” If they chose to leave, they would forfeit any right to a portion of the crop. Across the former Confederacy at the end of the war, it was evident that the former white economic elite was determined to continue to control and constrain African Americans.

The Battle over Political Reconstruction

The question of how to reconstruct the South’s political structure centered on deciding which governments would constitute authority in the defeated states. As Union forces advanced into the Confederacy during the Civil War, President Lincoln in 1862 had named military governors for conquered Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana. By the end of the following year, he had formulated a plan for regular governments in those states and any others that might be liberated from Confederate rule.

LINCOLN’S plan AND CONGRESS’S RESPONSE In late 1863, President Lincoln had issued a Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, under which any former Rebel state could form a Union government whenever a number equal to 10 percent of those who had voted in 1860 took an oath of allegiance to the Constitution and the Union and had received a presidential pardon. Participants also had to swear support for laws and proclamations dealing with emancipation. Certain groups, however, were excluded from the pardon: Confederate officials; senior officers of the Confederate army and navy; judges, congressmen, and military officers of the United States who had left their federal posts to aid the rebellion; and those accused of failure to treat captured African American soldiers and their officers as prisoners of war.

Under this plan, governments loyal to the Union appeared in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana during the war, but Congress recognized neither their representatives nor their electoral votes in the 1864 presidential election. In the absence of specific provisions for Reconstruction in the Constitution, politicians disagreed as to where authority to restore Rebel states properly rested. Lincoln claimed the right to direct Reconstruction under the clause that set forth the presidential power to grant pardons and under the constitutional obligation of the United States to guarantee each state a republican form of government. Many Republican congressmen, however, argued that this obligation implied that Congress, not the president, should supervise Reconstruction.

A few conservative and most moderate Republicans supported Lincoln’s program of immediate restoration. The Radical Republicans, however, favored a sweeping transformation of southern society based upon granting freed slaves full-fledged citizenship. The Radicals hoped to reconstruct southern society so as to dismantle the planter elite and the Democratic party.

The Radical Republicans were talented, earnest legislators who insisted that Congress control the Reconstruction program. In 1864 they helped pass the Wade-Davis Bill, sponsored by Senator Benjamin Franklin Wade of Ohio and Representative Henry Winter Davis of Maryland. In contrast to Lincoln’s 10 percent plan, the Wade-Davis Bill would have required that a majority of white male citizens declare their allegiance and that only those who could take an “ironclad” oath (required of federal officials since 1862) attesting to their past loyalty could vote or serve in the state constitutional conventions. The conventions, moreover, would have to abolish slavery, exclude from political rights high-ranking civil and military officers of the Confederacy, and repudiate debts incurred during the conflict.

But the Wade-Davis Bill never became law: Lincoln vetoed it. In retaliation furious Republicans penned the Wade-Davis Manifesto, which accused the president of exceeding his constitutional authority. Lincoln offered his last view of Reconstruction in his final public address, on April 11, 1865. Speaking from the White House balcony, he pronounced that the Confederate states had never left the Union. Those states were simply “out of their proper practical relation with the Union,” and the object was to get them back “into their proper practical relation.” At a cabinet meeting, Lincoln proposed the creation of new southern state governments before Congress met in December. He shunned the vindictiveness of the Radicals. He wanted “no persecution, no bloody work,” no radical restructuring of southern social and economic life.

THE ASSASSINATION OF LINCOLN On the evening of April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary went to see a play at Ford’s Theatre. With his trusted bodyguard called away to Richmond and the policeman assigned to his theater box away from his post, Lincoln was defenseless as John Wilkes Booth slipped into the unguarded presidential box. Booth, a crazed actor and Confederate sympathizer, fired his pistol point-blank at the back of the president’s head. As the president slumped forward, Booth pulled out a knife, stabbed Lincoln’s aide, and jumped from the box to the stage, breaking his leg in the process. He then mounted a waiting horse and fled the city. The president died nine hours later. Accomplices of Booth had simultaneously targeted Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. Seward and four others, including his son, were victims of severe knife wounds. Johnson escaped injury, however, because his would-be assassin got cold feet and wound up tipsy in the barroom of the vice president’s hotel.

Booth was pursued into Virginia and killed in a burning barn. Three of his collaborators were convicted by a military court and hanged, along with the woman at whose boardinghouse they had plotted the attacks.

Johnson’s plan Lincoln’s death elevated to the White House Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, a combative man who lacked most presidential virtues. Johnson was provincial and bigoted—he harbored fierce prejudices. He was also short-tempered and impetuous. At the inaugural ceremonies in early 1865, he had delivered his vice-presidential address in a state of slurring drunkenness that embarrassed Lincoln and the nation. Johnson was a war (pro-Union) Democrat who had been put on the National Union ticket in 1864 as a gesture of unity. As a southerner, he had long been an advocate of the small farmers in opposition to the privileges of the large planters—“a bloated, corrupted aristocracy.” He also shared the racist attitudes of most white yeomen. “Damn the negroes,” he exclaimed to a friend during the war, “I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters.”

Johnson’s loyalty to the Union sprang from a strict adherence to the Constitution and a fervent belief in limited government. When discussing what to do with the former Confederate states, Johnson preferred the term restoration to reconstruction. In 1865, he declared that “there is no such thing as reconstruction. Those States have not gone out of the Union. Therefore reconstruction is unnecessary.” Like many other whites he also opposed the growing Radical sentiment to grant the vote to African Americans.

Andrew Johnson

A pro-Union Democrat from Tennessee.

Johnson’s plan to restore the Union thus closely resembled Lincoln’s. A new Proclamation of Amnesty, issued in May 1865, excluded not only those Lincoln had barred from pardon but also everybody with taxable property worth more than $20,000. They were allowed to make special applications for pardon directly to the president, and before the

Year was out Johnson had issued some thirteen thousand pardons.

Johnson followed up his amnesty proclamation with his own plan for readmitting the former Confederate states. In each state a native Unionist became provisional governor, with authority to call a convention of men elected by loyal voters. Johnson called upon the state conventions to invalidate the secession ordinances, abolish slavery, and repudiate all debts incurred to aid the Confederacy. Each state, moreover, had to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery. In his final public address, Lincoln had endorsed a limited black suffrage. Johnson repeated Lincoln’s advice. He reminded the provisional governor of Mississippi, for example, that the state conventions might “with perfect safety” extend suffrage to African Americans with education or with military service so as to “disarm the adversary,” the adversary being “radicals who are wild upon” giving all African Americans the right to vote.

The state conventions for the most part met Johnson’s requirements. But southern whites had accepted the situation because they thought so little had changed after all. Emboldened by Johnson’s indulgence, they ignored his pleas for moderation and conciliation. Suggestions of black suffrage were scarcely raised in the state conventions and promptly squelched when they were.

SOUTHERN INTRANSIGENCE When Congress met in December 1865, for the first time since the end of the war it faced the fact that the new state governments in the postwar South were remarkably like the Confederate ones. Southern voters had acted with extreme disregard for northern feelings. Among the new members presenting themselves to Congress were Georgia’s Alexander Stephens, former vice president of the Confederacy, now claiming a seat in the Senate, four Confederate generals, eight colonels, and six cabinet members. Congress forthwith denied seats to all such officials. It was too much to expect, after four bloody years, that the Unionists in Congress would welcome back ex-Confederate leaders.

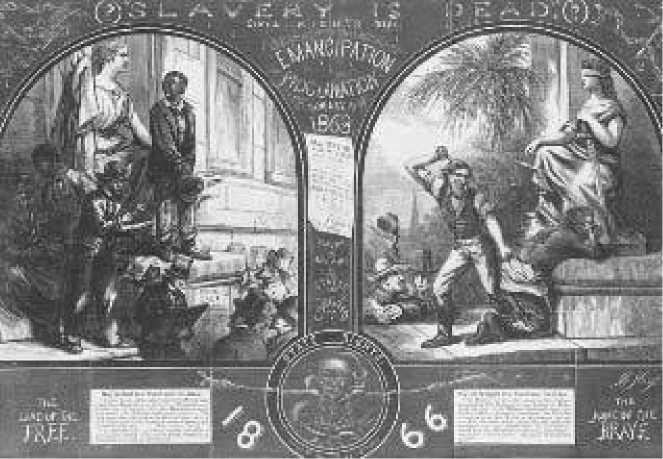

Furthermore, the new all-white southern state legislatures, in passing repressive “black codes” designed to restrict the freedom of African Americans, demonstrated that they intended to preserve slavery as nearly as possible. As one white southerner stressed, “The ex-slave was not a free man; he was a free Negro,” and the black codes were intended to highlight the distinction.

The black codes varied from state to state, but some provisions were common in many of them. Existing marriages, including common-law marriages, were recognized (although interracial marriages were prohibited), and testimony of blacks was accepted in legal cases involving blacks—and in six states in all cases. Blacks could own property. They could sue and be sued in the courts. On the other hand, they could not own farmland in Mississippi or city lots in South Carolina; they were required to buy special licenses to practice certain trades in Mississippi. Only a few states allowed blacks to serve on juries. Blacks who worked for whites were required to enter into labor contracts with their employers, to be renewed annually. Unemployed (“vagrant”) blacks were often arrested and punished with severe fines, and if unable to pay they were forced to labor in the fields of those who paid the courts for this source of cheap labor. In other words, aspects of slavery were simply being restored in another guise. When a freedman in South Carolina

(?) “Slavery Is Dead” (?)

Thomas Nast’s cartoon suggests that slavery was not dead in the postwar south.

Told a white employer that he wanted to get a federal army officer to review his labor contract, the employer killed him.

Faced with such blatant evidence of southern intransigence, moderate Republicans in Congress drifted toward the Radicals’ views. In early 1866 the new Congress set up a Joint Committee on Reconstruction, with nine members from the House and six from the Senate, to gather evidence of southern efforts to thwart Reconstruction. Initiative fell to determined Radical Republicans who knew what they wanted: Benjamin Franklin Wade of Ohio, George Washington Julian of Indiana, and—most conspicuously of all— Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

THE RADICAL REPUBLICANS Most Radical Republicans had been connected with the anti-slavery cause for decades. In addition, few could escape the bitterness bred by the long war or remain unaware of the partisan advantage that would come to the Republican party from black suffrage. The Republicans needed African American votes to maintain their control of Congress and the White House. They also needed to disenfranchise former Confederates to keep them from helping to elect Democrats eager to restore the old southern ruling class to power. In public, however, the Radical Republicans rarely disclosed such partisan self-interest. Instead, they asserted that the Republicans, the party of Union and freedom, could best guarantee the fruits of victory and that extending voting rights to African Americans would be the best way to promote their welfare.

The growing conflict of opinion over Reconstruction policy brought about an inversion in constitutional reasoning. Secessionists—and Andrew Johnson—were now arguing that the Rebel states had in fact remained in the Union, and some Radical Republicans were contriving arguments that they had left the Union after all. Thaddeus Stevens argued that the Confederate states should be viewed as conquered provinces, subject to the absolute will of the victors, and that the “whole fabric of southern society must be changed.” Most Republicans, however, held that the Confederate states continued to exist as entities, but by the acts of secession and war they had forfeited “all civil and political rights under the Constitution.” And Congress, not the president, was the proper authority to determine how and when such rights might be restored.

Johnson’s battle with congress a long year of political battling remained, however, before this idea triumphed. By the end of 1865, the Radical Republicans’ views had gained a majority in Congress, if one not yet large enough to override presidential vetoes. But the critical year of 1866 saw the gradual waning of Andrew Johnson’s power and influence, much of which was self-induced. Johnson first challenged Congress in 1866, when he vetoed a bill to extend the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau. For the time being, Johnson’s prestige remained sufficiently intact that the Senate upheld his veto.

Three days after the veto, however, during an impromptu speech, Johnson undermined his already weakening authority with a fiery assault upon the Radical Republican leaders. From that point forward, moderate Republicans deserted a president who had opened himself to counterattack. The Radical Republicans took the offensive. Johnson was “an alien enemy of a foreign state,” Stevens declared. Sumner called him “an insolent drunken brute,” a charge Johnson was open to because of his behavior at the 1865 inauguration.

In mid-March 1866 the Radical-led Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, written by Illinois senator Lyman Trumbull (who also drafted the Thirteenth Amendment). A response to the black codes and the neo-slavery system created by unrepentant southern state legislatures, it declared that “all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed,” were citizens entitled to “full and equal benefit of all laws.” The granting of citizenship to native-born blacks, Johnson fumed, exceeded the scope of federal power. It would, moreover, “foment discord among the races.” Johnson vetoed the bill, but this time, on April 9, Congress overrode the presidential veto. On July 16, it enacted a revised Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, again overriding a presidential veto. From that point on, Johnson steadily lost both public and political support.

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT To remove all doubt about the legality of the new Civil Rights Act, the joint committee recommended a new constitutional amendment, which passed Congress on June 16, 1866, and was ratified by the states two years later, on July 28, 1868. The Fourteenth Amendment went far beyond the Civil Rights Act by establishing a constitutional guarantee of basic citizenship for all Americans, including African Americans. The amendment reaffirms the state and federal citizenship of persons born or naturalized in the United States, and it forbids any state (the word state would be important in later litigation) to “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens,” to deprive any person (again an important term) “of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” or to “deny any person. . . the equal protection of the laws.” These three clauses have been the subject of many lawsuits, resulting in applications not widely, if at all, foreseen at the time. The “due-process clause” has come to mean that state as well as federal power is subject to the Bill of Rights, and it has been used to protect corporations, as legal “persons,” from “unreasonable” regulation by the states. The Fourteenth Amendment also prohibited the president from granting pardons to former Confederate leaders.

President Andrew Johnson’s home state was among the first to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. In Tennessee, which had more Unionists than any other Confederate state, the government had fallen under Radical Republican control. The state’s governor, in reporting the results to the secretary of the Senate, added, “Give my respects to the dead dog of the White House.” His words illustrate the growing acrimony on both sides of the Reconstruction debates. In May and July, race riots in Memphis and New Orleans added fuel to the flames. Both incidents involved indiscriminate massacres of blacks by local police and white mobs. The carnage, Radical Republicans argued, was the natural fruit of Andrew Johnson’s lenient policy toward white supremacists. “Witness Memphis, witness New Orleans,” Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner cried. “Who can doubt that the President is the author of these tragedies?”

Reconstructing the South

THE TRIUMPH OF CONGRESSIONAL RECONSTRUCTION As

1866 drew to an end, the congressional elections promised to be a referendum on the growing split between President Andrew Johnson and the Radical Republicans. To win votes, Johnson went on a speaking tour of the

Midwest. But his efforts backfired when several of his speeches turned into undignified shouting contests between him and his critics. In Cleveland, Johnson described the Radical Republicans as “factious, domineering, tyrannical” men, and he foolishly exchanged hot-tempered insults with a heckler. At another stop, while Johnson was speaking from the back of a railway car, the engineer mistakenly pulled the train out of the station, making the president appear quite the fool. Such incidents tended to confirm Johnson’s image as a “ludicrous boor” and a “drunken imbecile,” an image that Radical Republicans promoted. The 1866 congressional elections were a devastating defeat for Johnson; Republicans won more than a two-thirds majority in each house, a comfortable margin with which to override presidential vetoes.

The Republican-controlled Congress in fact enacted several important provisions even before the new members took office. Two acts passed in 1867 extended voting rights to African Americans in the District of Columbia and the territories. Another law provided that the new Congress would convene on March 4 instead of the following December, depriving Johnson of a breathing spell. On March 2, 1867, two days before the old Congress expired, it passed, over Johnson’s vetoes, three crucial laws promoting what came to be called “Congressional Reconstruction”: the Military Reconstruction Act, the Command of the Army Act (an amendment to an army appropriation), and the Tenure of Office Act.

Congressional Reconstruction was designed to prevent white southerners from manipulating the reconstruction process. The Command of the Army Act required that all orders from the commander in chief go through the headquarters of the general of the army, a post then held by Ulysses S. Grant. The Radical Republicans distrusted President Johnson and trusted General Grant, who was already leaning their way. The Tenure of Office Act required Senate permission for the president to remove any federal officeholder whose appointment the Senate had confirmed. The purpose of at least some congressmen was to retain Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the one Radical Republican sympathizer in Johnson’s cabinet.

The Military Reconstruction Act was hailed—or denounced—as the triumphant victory of Radical Reconstruction, for it set a precedent among former slave societies in providing voting rights to freed slaves almost immediately after emancipation. It also represented the nation’s first effort in military-enforced nation building. The North’s effort to “reconstruct” the South by force after the Civil War set a precedent for future American military occupations and attempted social transformations. The act declared that “no legal state governments or adequate protection for life and property now exists in the rebel States.” One state, Tennessee, was exempted from the application of the new act because it had already ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. The other ten southern states were divided into five military districts, and the commanding officer of each was authorized to keep order and protect the “rights of persons and property.” The Military Reconstruction Act then stipulated that new constitutions in each of the former Confederate states were to be framed by conventions elected by male citizens aged twenty-one and older “of whatever race, color, or previous condition.” Each state constitution had to guarantee the right of African American males to vote. Once the constitution was ratified by a majority of voters and accepted by Congress, other criteria had to be met. The new state legislature had to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, and once the amendment became part of the Constitution, any given state would be entitled to representation in Congress.

Several hundred African American delegates participated in the statewide political conventions. Most had been selected by local political meetings or churches, fraternal societies, Union Leagues, or black army units from the North, although a few simply appointed themselves. The African American delegates “ranged [across] all colors and apparently all conditions,” but free mulattoes from the cities played the most prominent roles. At Louisiana’s Republican state convention, for instance, nineteen of the twenty black delegates had been born free. President Johnson reluctantly appointed military commanders under the new Military Reconstruction Act. Before the end of 1867, new elections had been held in all the states but Texas, and blacks participated in high numbers, giving virtually all of their votes to Republican candidates.

Some people expected the Supreme Court to strike down the act, and no process existed for the new elections. Congress quickly remedied that on March 23, 1867, with the Second Reconstruction Act, which directed the army commanders to register all adult men who swore they were qualified. A Third Reconstruction Act, passed on July 19, directed registrars to go beyond the loyalty oath and determine each person’s eligibility to take it and authorized district army commanders to remove and replace officeholders of any existing “so-called state” or division thereof. Before the end of 1867, new elections had been held in all the states but Texas.

Having clipped the president’s wings, the Republican Congress moved a year later to safeguard its Reconstruction program from possible interference by the Supreme Court. On March 27, 1868, Congress simply removed the power of the Supreme Court to review cases arising under the Military Reconstruction Act, which Congress clearly had the right to do under its

Power to define the Court’s appellate jurisdiction. The Court accepted this curtailment of its authority on the same day it affirmed the principle of an “indestructible Union” in Texas v. White (1869). In that case the Court also asserted the right of Congress to reframe state governments, thus endorsing the Radical Republican point of view.

THE IMPEACHMENT AND TRIAL OF JOHNSON By 1868, Radical Republicans had decided that Andrew Johnson must be removed from office. The Republicans had unsuccessfully tried to impeach Johnson early in 1867, alleging a variety of flimsy charges, none of which represented an indictable crime. Then Johnson himself provided the occasion for impeachment when he deliberately violated the Tenure of Office Act in order to test its constitutionality. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had become a thorn in Johnson’s side, refusing to resign despite his disagreements with the president’s Reconstruction policy. On August 12, 1867, during a congressional recess, Johnson suspended Stanton and named General Ulysses S. Grant in his place. When the Senate refused to confirm Johnson’s action, however, Grant returned the office to Stanton.

The Radical Republicans now saw their chance to remove the president. On February 24, 1868, the Republican-dominated House passed eleven articles of impeachment by a party-line vote of 126 to 47. Most of the articles focused on the charge that Johnson had unlawfully removed Secretary of War Stanton.

The Senate trial began on March 5, 1868, and continued until May 26, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding. It was a great spectacle before a packed gallery. The five-week trial ended in May 1868, and the Senate voted 35 to 19 for conviction, only one vote short of the two thirds needed for removal from office. Although the Senate failed to remove Johnson, the trial crippled his already weakened presidency. In 1868, Johnson sought the Democratic presidential nomination but lost to New York governor Horatio Seymour, who then lost to the Republican, Ulysses S. Grant, in the general election. The impeachment of Johnson was in the end a great political mistake, for the failure to remove the president damaged Radical Republican morale and support. Nevertheless, the Radical cause did gain something: to stave off impeachment, Johnson agreed not to obstruct the process of Congressional-led Reconstruction.

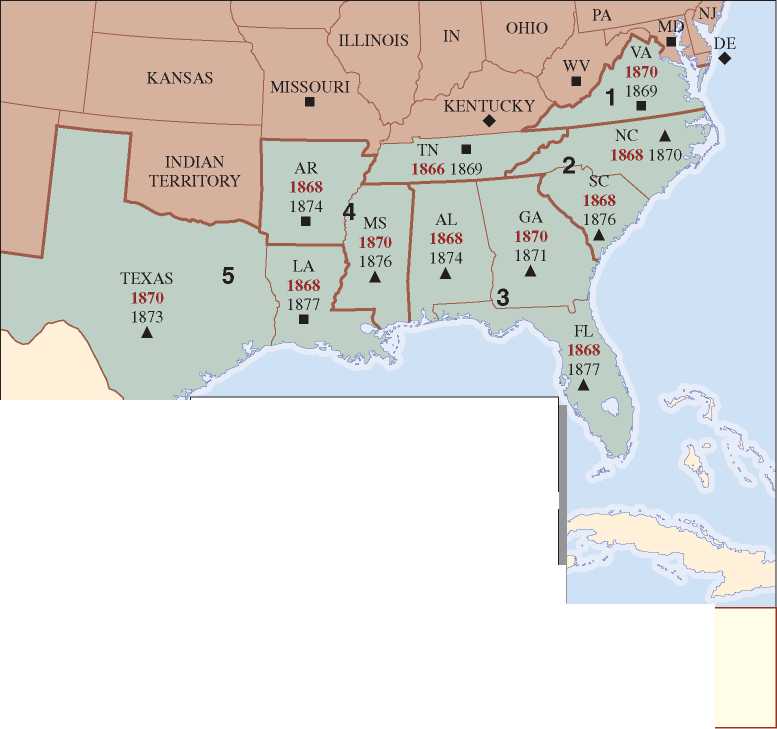

REPUBLICAN RULE IN THE SOUTH In June 1868, Congress agreed that eight southern states—all but Virginia, Mississippi, and Texas—had met the more stringent conditions for readmission. Congress rescinded Georgia’s admission, however, when the state legislature expelled twenty-eight African American members and seated former Confederate leaders. The federal military commander in Georgia then forced the legislature to reseat the black members and remove the Confederates, and the state was compelled to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment before being admitted in July 1870. Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia had returned earlier in 1870, under the added requirement that they, too, ratify the Fifteenth Amendment. That amendment, submitted to the states in 1869 and ratified in 1870, forbids the states to deny any person the vote on grounds of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Kentucky, the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln, was the only state in the nation that failed to ratify all three of the constitutional amendments related to ending slavery—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth.

Long before the new governments were established, groups promoting the Republican party had begun to spring up in the South, chiefly sponsored by the Union League, founded in Philadelphia in 1862 to support the Union. League recruiters in the South enrolled African Americans and loyal whites, initiated them into the secrets and rituals of the order, and instructed them “in their rights and duties.” Their recruiting efforts were so successful that in 1867, on the eve of South Carolina’s choice of convention delegates, the league reported eighty-eight chapters, which claimed to have enrolled almost every adult black male in the state.

The Reconstructed South

THE freed slaves African Americans in the postwar South were active agents in affecting the course of Reconstruction, though it was not an easy process. During the era of Reconstruction, whites, both northern and southern, harbored racist views of blacks. A northern journalist traveling in the South after the war reported that the “whites seem wholly unable to comprehend that freedom for the negro means the same thing as freedom for them.” Whites used terror, intimidation, and violence to suppress black efforts to gain social and economic equality. In Texas a white farmer told a former slave that his freedom would do him “damned little good. . . as I intend to shoot you”—and he did. The Civil War had brought freedom to enslaved African Americans, but it did not bring them protection against exploitation or abuse.

Participation in the Union army or navy had provided many freedmen with training in leadership. Black military veterans would form the core of the first generation of African American political leaders in the postwar South. Military service gave many former slaves their first opportunities to learn to read and write. Army life also alerted them to new opportunities for economic advancement, social respectability, and civic leadership. Fighting for the Union cause also instilled a fervent sense of nationalism. A Virginia freedman explained that the United States was “now our country—made emphatically so by the blood of our brethren.”

Former slaves established churches after the war, which quickly formed the foundation of African American community life. Many blacks preferred the Baptist denomination, in part because its decentralized structure allowed each congregation to worship in its own way. By 1890 over 1.3 million African Americans in the South had become Baptists, nearly three times as many as had joined any other black denomination. In addition to forming viable new congregations, freed African Americans organized thousands of fraternal, benevolent, and mutual-aid societies, as well as clubs, lodges, and associations. Memphis, for example, had over two hundred such organizations; Richmond boasted twice that number.

Freed blacks also hastened to reestablish their families. Marriages that had been prohibited during slavery were now legitimized through the assistance of the Freedmen’s Bureau. By 1870 a preponderant majority of former slaves were living in two-parent households. With little money or technical training, freed blacks faced the prospect of becoming wage laborers. Because there were so few banks left in the South, it was virtually impossible for former slaves to get loans to buy farm land. For many freed blacks (and poor whites) the primary vocational option after the war was sharecropping, in which the crop produced was divided between the tenant farmer and the landowner. Sharecropping enabled mothers and wives to contribute directly to the family’s income.

African American communities in the postwar South also sought to establish schools. Planters had denied education to blacks in part because they feared that literate slaves would read abolitionist literature and organize uprisings. After the war the white elite worried that formal education would encourage poor whites and poor blacks to leave the South in search of better social and economic opportunities. Economic leaders wanted to protect the competitive advantage afforded by the region’s low-wage labor market. “They didn’t want us to learn nothin’,” one former slave recalled. “The only thing we had to learn was how to work.”

White opposition to education for blacks made education all the more important to African Americans. South Carolina’s Mary McLeod Bethune, the fifteenth child of former slaves, reveled in the opportunity to gain an education: “The whole world opened to me when I learned to read.” She walked five miles to school as a child, earned a scholarship to college, and went on to become the first black woman to found a school that became a four-year college, Bethune-Cookman, in Daytona Beach, Florida.

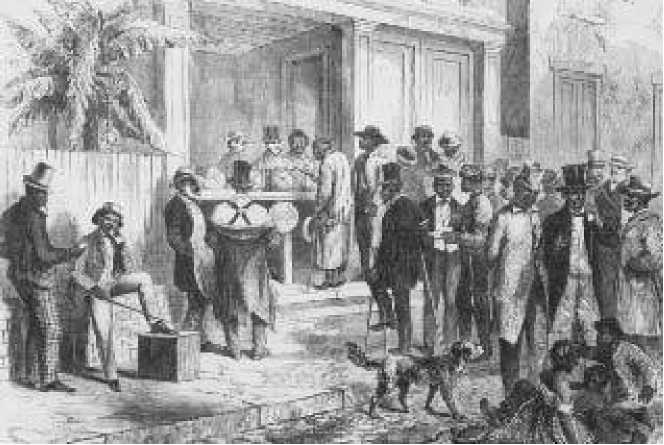

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SOUTHERN POLITICS In the postwar South the new role of African Americans in politics caused the most controversy. If largely uneducated and inexperienced in the rudiments of politics, southern blacks were little different from the millions of newly enfranchised propertyless whites in the age of Andrew Jackson’s political reforms or immigrants in postwar cities. Some freedmen frankly confessed their disadvantages. Beverly Nash, an African American delegate to the South Carolina convention of 1868, told his colleagues: “I believe, my friends and fellow-citizens, we are not prepared for this suffrage. But we can learn. Give a man tools and let him commence to use them, and in time he will learn a trade. So it is with voting.”

By 1867, however, former slaves had begun to gain political influence and vote in large numbers, and this development revealed emerging tensions within the African American community. Some southern blacks resented the presence of northern brethren who moved south after the war, while others complained that few ex-slaves were represented in leadership positions. There developed real tensions in the black community between the few who owned

Freedmen voting in New Orleans

The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, guaranteed at the federal level the right of citizens to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” But former slaves had been registering to vote—and voting in large numbers—in state elections since 1867, as in this scene.

Property and the many who did not. In North Carolina by 1870, for example, less than 7 percent of blacks owned land, and most of them owned only a few acres; half of black property owners had less than twenty acres. Northern blacks and the southern free black elite, most of whom were urban dwellers and many of whom were mulattoes, often opposed efforts to redistribute land to the freedmen, and many insisted that political equality did not mean social equality. As a black Alabama leader stressed, “We do not ask that the ignorant and degraded shall be put on a social equality with the refined and intelligent.” In general, however, unity rather than dissension prevailed, and African Americans focused on common concerns such as full equality under the law.

Brought suddenly into politics in times that tried the most skilled of statesmen, many African Americans served with distinction. Nonetheless, the derisive label “black Reconstruction,” used by later critics, exaggerates African American political influence, which was limited mainly to voting. Such criticism also overlooks the political clout of the large number of white Republicans, especially in the mountain areas of the Upper South, who also favored the Radical plan for Reconstruction. Only one of the new state conventions, South Carolina’s, had a black majority, seventy-six to forty-one. Louisiana’s was evenly divided racially, and in only two other conventions were more than 20 percent of the members black: Florida’s, with 40 percent, and Virginia’s, with 24 percent. The Texas convention was only 10 percent black, and North Carolina’s was 11 percent—but that did not stop a white newspaper from calling it a body consisting of “baboons, monkeys, mules. . . and other jackasses.”

In the new state governments any African American participation was a novelty. Although some six hundred blacks—most of them former slaves— served as state legislators, no black man was ever elected governor, and only a few served as judges. In Louisiana, however, Pinckney Pinchback, a northern black and former union soldier, won the office of lieutenant governor and served as acting governor when the white governor was indicted for corruption. Several African Americans were elected lieutenant governor, state treasurer, or secretary of state. There were two black senators in Congress, Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce, both Mississippi natives who had been educated in the North, and fourteen black members of the House of Representatives during Reconstruction.

“carpetbaggers” and “scalawags” The top positions in postwar southern state governments went for the most part to white Republicans, whom the opposition whites labeled “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags,” depending upon their place of birth. Northerners who allegedly rushed

South with all their belongings in carpetbags to grab the political spoils were more often than not Union veterans who had arrived as early as 1865 or 1866, drawn South by the hope of economic opportunity and other attractions that many of them had seen in their Union service. Many other so-called carpetbaggers were teachers, social workers, or preachers animated by a sincere missionary impulse.

The scalawags, or native white Republicans, were even more reviled and misrepresented. A Nashville newspaper editor called them the “merest trash.” Most scalawags had opposed secession, forming a Unionist majority in many mountain counties as far south as Georgia and Alabama and especially in the hills of eastern Tennessee. Among the so-called scalawags were several distinguished figures, including the former Confederate general James Longstreet, who decided after Appomattox that the Old South must change its ways. He became a successful cotton broker in New Orleans, joined the Republican party, and supported the Radical Reconstruction program. Other scalawags were former Whigs attracted by the Republican party’s economic program of industrial and commercial expansion.

THE RADICAL REPUBLICAN RECORD Former Confederates resented the new state constitutions because of their provisions allowing for black voting and civil rights. Yet most of those constitutions remained in effect for some years after the end of Radical Republican control, and later constitutions incorporated many of their features. Conspicuous among the Radical innovations were such steps toward greater democracy as requiring universal manhood suffrage, reapportioning legislatures more nearly according to population, and making more state offices elective. In South Carolina, former Confederate leaders opposed the Radical state legislature not simply because of its black members but also because lower-class whites were enjoying unprecedented political power too.

Given the hostile circumstances under which the Radical governments operated, their achievements were remarkable. They constructed an extensive railroad network and established state-supported public school systems. Some six hundred thousand black pupils were enrolled in southern schools by 1877. State governments under the Radicals also gave more attention to the poor and to orphanages, asylums, and institutions for the deaf and the blind of both races. Public roads, bridges, and buildings were repaired or rebuilt. African Americans achieved rights and opportunities that would never again be taken away, at least in principle: equality before the law and the rights to own property, carry on business, enter professions, attend schools, and learn to read and write.

RECONSTRUCTION, 1865-1877

? States with Reconstruction governments 1868 Date of readmission to the Union 1870 Date of reestablishment of conservative rule 2 Military districts set up by the Reconstruction Act of 1867 Means by Which Slavery Was Abolished A Emancipation Proclamation, 1863 ¦ State action

¦ Thirteenth Amendment, 1865

How did the Military Reconstruction Act reorganize governments in the South in the late 1860s and 1870s? What did the former Confederate states have to do to be readmitted to the Union? Why did “Conservative” parties gradually regain control of the South from the Republicans in the 1870s?

Yet several of these Republican state regimes also engaged in corrupt practices. Bids for state government contracts were accepted at absurdly high prices, and public officials took their cut. Public money and public credit were often awarded to privately owned corporations, notably railroads, under conditions that invited influence peddling. Corruption was not invented by the Radical Republican regimes, nor did it die with them. Louisiana’s “carpetbag” governor recognized as much. “Why,” he said, “down here everybody is demoralized. Corruption is the fashion.”

RELIGION AND RECONSTRUCTION The religious community played a critical role in the implementation and ultimate failure of Radical Reconstruction, and religious commentators offered quite different interpretations of what should be done with the defeated South. Thaddeus Stevens and many other Radical Republican leaders who had spent their careers promoting the abolition of slavery and racial equality were motivated primarily by religious ideals and moral fervor. They wanted no compromise with racism. Likewise, most of the Christian missionaries who headed south after the Civil War brought with them a progressive vision of a biracial “beloved community” emerging in the reconstructed South, and they strove to promote social and political equality for freed slaves. For these crusaders, civil rights was a sacred cause. They used Christian principles to challenge the prevailing theological and “scientific” justifications for racial inferiority. They also promoted Christian solidarity across racial and regional lines.

At the same time, the Protestant denominations, all of which had split into northern and southern branches over the issues of slavery and secession, struggled to reunite after the war. A growing number of northern ministers promoted reconciliation between the warring regions after the Civil War. These “apostles of forgiveness” prized white unity over racial equality. For example, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, the powerful New York minister whose sister Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, wanted white southern planters—rather than federal officials or African Americans themselves—to oversee Reconstruc

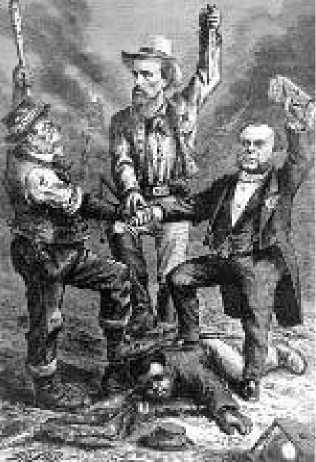

The “white republic”

This cartoon illustrates white unity against racial equality.

Tion. Not surprisingly, Beecher’s views gained widespread support among evangelical ministers in the South.

The collapse of the Confederacy did not prompt southern whites to abandon their belief that God was on their side. In the wake of defeat and emancipation, white southern ministers reassured their congregations that they had no reason to question the moral foundations of their region or their defense of white racial superiority. For African Americans, however, the Civil War and emancipation demonstrated that God was on their side. Emancipation was in their view a redemptive act through which God wrought national regeneration. African American ministers were convinced that the United States was indeed a divinely inspired nation and that blacks had a providential role to play in its future. Yet neither black nor idealistic white northern ministers could stem the growing chorus of whites who were willing to abandon goals of racial equality in exchange for national religious reconciliation. By the end of the nineteenth century, mainstream American Protestantism promoted the image of a “white republic” that conflated whiteness, godliness, and nationalism.

The Grant Years

Ulysses S. Grant, who served as president during the collapse of Republican rule in the South, brought to the White House little political experience. But in 1868 northern voters supported the “Lion of Vicksburg” because of his record as the Union army commander. He was the most popular man in the nation. Both parties wooed him, but his falling-out with President Andrew Johnson had pushed him toward the Republicans. They were, as Thaddeus Stevens said, ready to “let him into the church.” the election of 1868 The Republican party platform of 1868 endorsed congressional Reconstruction. One plank cautiously defended black suffrage as a necessity in the South but a matter each northern state should settle for itself. Another urged payment of the national debt “in the utmost good faith to all creditors,” which meant in gold. More important than the platform were the great expectations of a heroic soldier-president and his slogan, “Let us have peace.”

The Democrats took opposite positions on both Reconstruction and the debt. The Republican Congress, the Democratic party platform charged, instead of restoring the Union had “so far as in its power, dissolved it, and subjected ten states, in the time of profound peace, to military despotism and Negro supremacy.” As for the federal debt, the party endorsed Representative George H. Pendleton’s “Ohio idea” that, since most war bonds had been bought with depreciated greenbacks, they should be paid off in greenbacks rather than in gold. The Democratic Convention nominated Horatio Seymour, wartime governor of New York, who made it a closer race than the electoral vote revealed. While Grant swept the Electoral College by 214 to 80, his popular majority was only 307,000 out of a total of over 5.7 million votes. More than 500,000 African American voters accounted for Grant’s margin of victory.

Grant had proved himself a great military leader, but as the youngest president ever (forty-six years old at the time of his inauguration), he was often blind to the political forces and influence peddlers around him. He was awestruck by men of wealth and unaccountably loyal to some who betrayed his trust, and he passively followed the lead of Congress.

Grant betrayed a fatal gift for losing men of talent and integrity from his cabinet. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish of New York turned out to be a happy exception; he guided foreign policy throughout the Grant presidency. Other than Fish, however, the Grant cabinet overflowed with incompetents.

THE GOVERNMENT DEBT Financial issues dominated Grant’s presidency. After the war the Treasury had assumed that the $432 million worth of greenbacks issued during the conflict would be retired from circulation and that the nation would revert to a “hard-money” currency—gold coins. But many agrarian and debtor groups resisted any contraction of the money supply resulting from the elimination of greenbacks, believing that it would mean lower prices for their crops and more difficulty repaying long-term debts. They were joined by a large number of Radical Republicans who thought that a combination of high tariffs and inflation would generate more rapid economic growth. In 1868 congressional supporters of such a “soft-money” policy halted the withdrawal of greenbacks from circulation. There matters stood when Grant took office.

The “sound-money” (or hard-money) advocates, mostly bankers and merchants, claimed that Grant’s election was a mandate to save the country from the Democrats’ “Ohio idea” of using greenbacks to repay government bonds. The influential hard-money advocates also reflected the deeply ingrained popular assumption that gold coins were morally preferable to paper currency. Grant agreed as well. On March 18, 1869, the Public Credit Act, which said that the federal debt must be paid in gold, became the first act of Congress that Grant signed.

SCANDALS The complexities of the “money question” exasperated Grant, but that was the least of his worries, for his administration soon fell into a cesspool of scandal. In the summer of 1869, two unscrupulous financial buccaneers, Jay Gould and James Fisk, connived with the president’s brother-in-law to corner the nation’s gold market. That is, they would create a public craze for gold by purchasing massive quantities of the precious yellow metal. As more buyers joined the frenzy, the value of gold would soar. The only danger to the scheme lay in the possibility that the federal Treasury would burst the bubble by selling large amounts of gold, which would deflate its value.

Grant apparently smelled a rat from the start, but he was seen in public with the speculators, leading people to think that he supported the run on gold. As the rumor spread on Wall Street that the president was pro-gold, the value of gold rose from $132 to $163 an ounce. Finally, on Black Friday, September 24, 1869, Grant ordered the Treasury to sell a large quantity of gold, and the bubble burst. Fisk got out by repudiating his agreements and hiring thugs to intimidate his creditors. “Nothing is lost save honor,” he said.

The plot to corner the gold market was only the first of several scandals that rocked the Grant administration. During the presidential campaign of 1872, the public learned about the corruption of the Credit Mobilier of America, a sham construction company run by directors of the Union Pacific Railroad who had milked the Union Pacific for exorbitant fees in order to line the pockets of the insiders who controlled both firms. Union Pacific shareholders were left holding the bag. The schemers bought political support by giving congressmen shares of stock in the enterprise. This chicanery had transpired before Grant’s election in 1868, but it now touched a number of prominent Republicans. The beneficiaries of the scheme included Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, later vice president, and Representative James A. Garfield, later president. Of the thirteen members of Congress involved, only two were censured.

Even more odious disclosures soon followed, some involving the president’s cabinet. The secretary of war, it turned out, had accepted bribes from merchants who traded with Indians at army posts in the West. At the same time, post-office contracts, it was revealed, went to carriers who offered the highest kickbacks. The secretary of the Treasury had awarded a political friend a commission of 50 percent for the collection of overdue taxes. In St. Louis a “whiskey ring” bribed tax collectors to bilk the government out of millions of dollars in revenue. Grant’s private secretary was enmeshed in that scheme, taking large sums of money and other valuables in return for inside information. There is no evidence that Grant himself was ever involved in, or personally profited from, any of the fraud, but his poor choice of associates and his gullibility earned him widespread criticism. Democrats castigated Republicans for their “monstrous corruption and extravagance.”

WHITE TERROR President Grant initially fought hard to enforce t

World History

World History