The cinema is a complicated medium, and before it could be invented, several technological requirements had to be met.

Preconditions for Motion Pictures

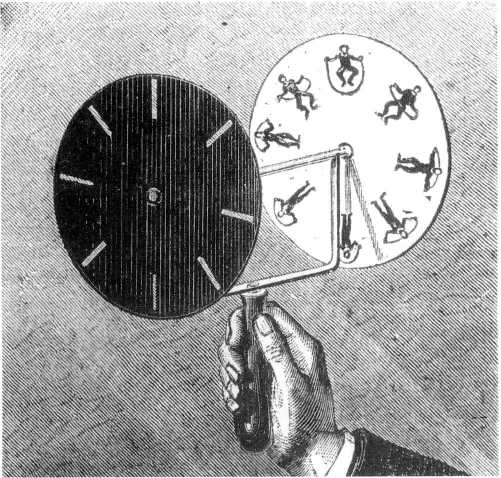

First, scientists had to realize that the human eye will perceive motion if a series of slightly different images is placed before it in rapid succession—minimally, around sixteen per second. During the nineteenth century, scientists explored this property of vision. Several optical toys were marketed that gave an illusion of movement by using a small number of drawings, each altered somewhat. In 1832, Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau and Austrian geometry professor Simon Stampfer independently created the optical device that came to be called the Phenakistoscope (1.1). The Zoetrope, invented in 1833, contained a series of drawings on a narrow strip of paper inside a revolving drum (1.2). The Zoetrope was widely sold after 1867, along with other optical toys. Similar principles were later used in films, but in these toys, the same action was repeated over and over.

A second technological requirement for the cinema was the capacity to project a rapid series of images on a surface. Since the seventeenth century, entertainers and educators had been using “magic lanterns” to project glass lantern slides, but there had been no way to flash large numbers of images fast enough to create the illusion of motion.

A third prerequisite for the invention of the cinema was the ability to use photography to make successive pictures on a clear surface. The exposure time would have to be short enough to take sixteen or more frames in a single second. Such techniques came about slowly. The first still photograph was made on a glass plate in 1826 by Claude Niepce, but it required an exposure time of eight hours. For years, photographs were made on glass or metal, without the use of negatives, so only one copy of each image was possible; exposures took several minutes each. In 1839, Henry Fox Talbot introduced negatives made on paper. At about this same time, it became possible to print photographic images on glass lantern slides and project them. Not until 1878, however, did split-second exposure times become feasible.

Fourth, the cinema would require that photographs be printed on a base flexible enough to be passed through a camera rapidly. Strips or discs of glass could be used, but only a short series of images could be registered on them. In 1888, George Eastman devised a still camera that made photographs on rolls of sensitized paper. This camera, which he named the Kodak, simpli-

1.1 A phenakistoscope’s spinning disc of figures gives the illusion of movement when the viewer looks through a slot in the stationary disc.

1.2 Looking through the slots in a revolving Zoetrope, the viewer receives an impression of movement.

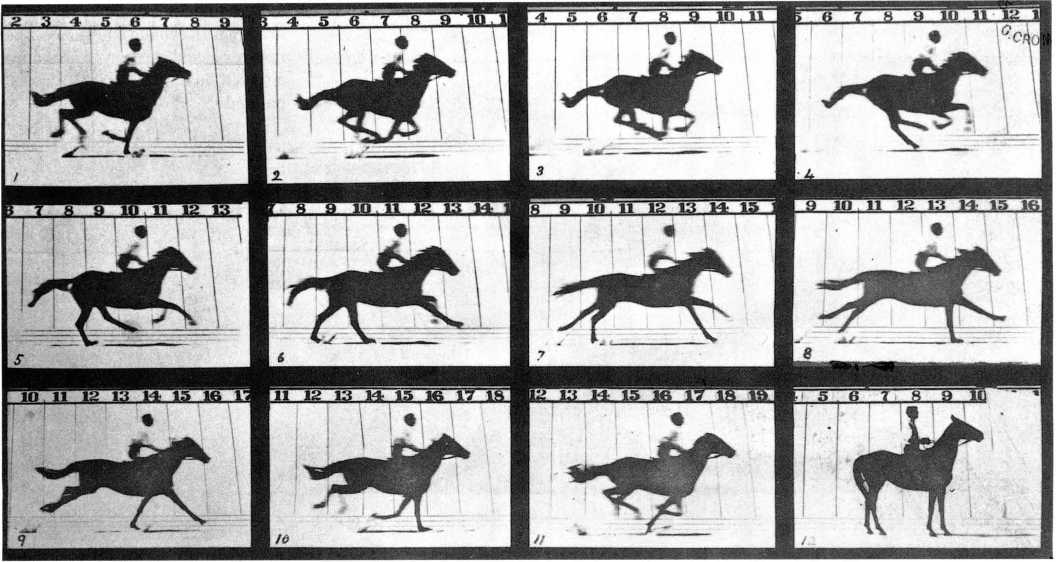

1.3 One of Muybridge’s earliest motion studies, photographed on June 19, 1878.

Fied photography so that unskilled amateurs could take pictures. The next year Eastman introduced transparent celluloid roll film, creating a breakthrough in the move toward cinema. The film was intended for still cameras, but inventors could use the same flexible material in designing machines to take and project motion pictures (though it was apparently about a year before the stock was improved enough to be practical).

Fifth, and finally, experimenters needed to find a suitable intermittent mechanism for their cameras and projectors. In the camera, the strip of film had to stop briefly while light entered through the lens and exposed each frame; a shutter then covered the film as another frame moved into place. Similarly, in the projector, each frame stopped for an instant in the aperture while a beam of light projected it onto a screen; again a shutter passed behind the lens while the filmstrip moved. At least sixteen frames had to slide into place, stop, and move away each second. (A strip of film sliding continuously past the gate would create a blur unless the light source was quite dim.) Fortunately, other inventions of the century also needed intermittent mechanisms to stop and start quickly. For example, the sewing machine (invented in 1846) advanced strips of fabric several times per second while a needle pierced them. Intermittent mechanisms usually consisted of a gear with slots or notches spaced around its edge.

By the 1890s, all the technical conditions necessary for the cinema existed. The question was Who would bring the necessary elements together in a way that could be successfully exploited on a wide basis?

Major Precursors ofMotion Pictures

Some inventors made important contributions without creating moving photographic images. Several men were simply interested in analyzing motion. In 1878, exgovernor of California Leland Stanford asked photographer Eadweard Muybridge to find a way of photographing running horses to help study their gaits. Muybridge set up a row of twelve cameras, each making an exposure in one-thousandth of a second. The photos recorded one-half-second intervals of movement (1.3). Muybridge later made a lantern to project moving images of horses, but these were drawings copied from his photographs onto a revolving disc. Muybridge did not go on to invent motion pictures, but he made a major contribution to anatomical science through thousands of motion studies using his multiple-camera setup.

In 1882, inspired by Muybridge’s work, French physiologist Etienne Jules Marey studied the flight of birds and other rapid animal movements by means of a photographic gun. Shaped like a rifle, it exposed twelve images around the edge of a circular glass plate that

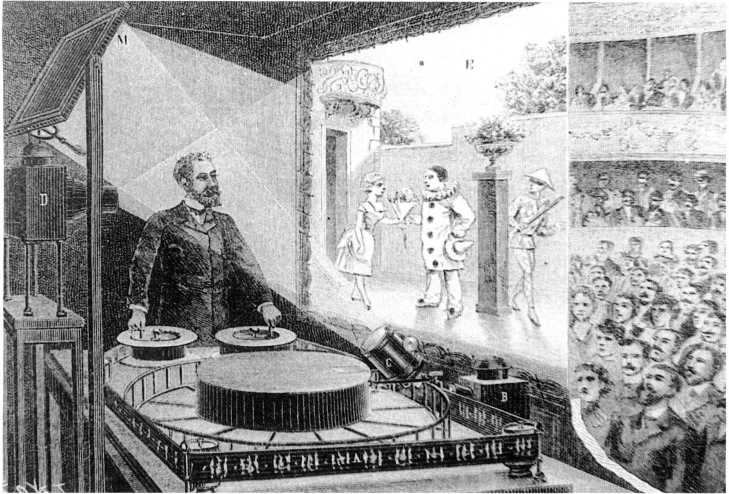

1.4 Using long flexible bands of drawings, Reynaud’s Praxinoscope rear-projected cartoon figures onto a screen on which the scenery was painted.

Made a single revolution in one second. In 1888, Marey built a box-type camera that used an intermittent mechanism to expose a series of photographs on a strip of paper film at speeds of up to 120 frames per second. Marey was the first to combine flexible film stock and an intermittent mechanism in photographing motion. He was interested in analyzing movements rather than in reproducing them on a screen, but his work inspired other inventors. During this same period, many other scientists used various devices to record and analyze movement.

A fascinating and isolated figure in the history of the invention of the cinema was Frenchman Emile Rey-naud. In 1877, he had built an optical toy, the Projecting Praxinoscope. This was a spinning drum, rather like the Zoetrope, but one in which viewers saw the moving images in a series of mirrors rather than through slots. Around 1882, he devised a way of using mirrors and a lantern to project a brief series of drawings on a screen. In 1889, Reynaud exhibited a much larger version of the Praxinoscope. From 1892 on, he regularly gave public performances using long, broad strips of hand-painted frames (1.4). These were the first public exhibitions of moving images, though the effect on the screen was jerky and slow. The labor involved in making the bands meant that Reynaud’s films could not easily be reproduced. Strips of photographs were more practical, and in 1895 Reynaud started using a camera to make his Praxinoscope films. By 1900, he was out of business, however, due to competition from other, simpler motion-picture projection systems. In despair, he destroyed his machines, though replicas have been constructed.

Another Frenchman came close to inventing the cinema as early as 1888—six years before the first commercial showings of moving photographs. That year, Augustin Le Prince, working in England, was able to make some brief films, shot at about sixteen frames per second, using Kodak’s recently introduced paper roll film. To be projected, however, the frames needed to be printed on a transparent strip; lacking flexible celluloid, Le Prince apparently was unable to devise a satisfactory projector. In 1890, while traveling in France, he disappeared, along with his valise of patent applications, creating a mystery that has never been solved. Thus his camera was never exploited commercially and had virtually no influence on the subsequent invention of the cinema.

An International Process oflnvention

It is difficult to attribute the invention of the cinema to a single source. There was no one moment when the cinema emerged. Rather, the technology of the motion picture came about through an accumulation of contributions, primarily from the United States, Germany, England, and France.

Edison, Dickson, and the Kinetoscope In 1888, Thomas Edison, already the successful inventor of the phonograph and the electric lightbulb, decided to design machines for making and showing moving photographs. Much of the work was done by his assistant, W. K. L.

Dickson. Since Edison’s phonograph worked by recording sound on cylinders, the pair tried fruitlessly to make rows of tiny photographs around similar cylinders. In 1889, Edison went to Paris and saw Marey’s camera,

1.5 The Kinetoscope was a peephole device that ran the film around a series of rollers. Viewers activated it by putting a coin in a slot.

Which used strips of flexible film. Dickson then obtained some Eastman Kodak film stock and began working on a new type of machine. By 1891, the Kinetograph camera and Kinetoscope viewing box (1.5) were ready to be patented and demonstrated. Dickson sliced sheets of Eastman film into strips 1 inch wide (roughly 35 millimeters), spliced them end to end, and punched four holes on either side of each frame so that toothed gears could pull the film through the camera and Kinetoscope. Dickson’s early decisions influenced the entire history of the cinema; 35 mm film stock with four perforations per frame has remained the norm. (Amazingly, an original Kinetoscope film can be shown on a modern projector.) Initially, however, the film was exposed at about forty-six frames per second—much faster than the average speed later adopted for silent filmmaking.

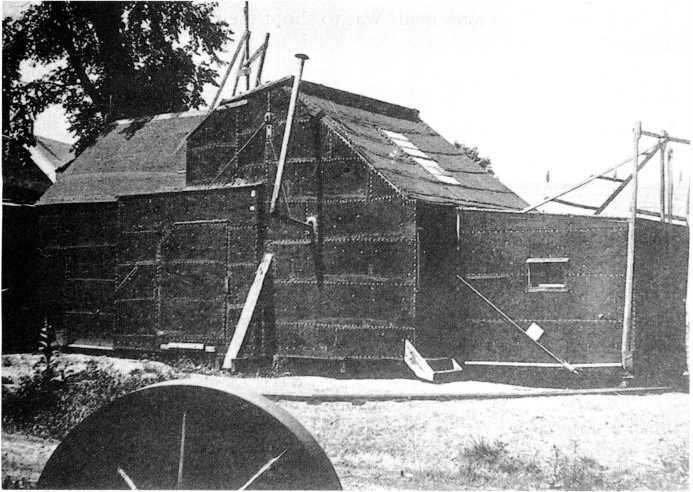

Edison and Dickson needed films for their machines before they could exploit them commercially. They built a small studio, called the Black Maria, on the grounds of Edison’s New Jersey laboratory and were ready for production by January 1893 (1.6). The films lasted only twenty seconds or so—the longest run of film that the Kinetoscope could hold. Most films featured well-known sports figures, excerpts from noted vaudeville acts, or performances by dancers or acrobats (1.7). Annie Oakley displayed her riflery and a bodybuilder flexed his muscles. A few Kinetoscope shorts were knockabout comic skits, forerunners of the story film.

1.6 Edison’s studio was named after the police paddy wagons, or Black Marias, that it resembled. The slanted portion of the roof opened to admit sunlight for filming, and the whole building revolved on a track to catch optimal sunlight.

1.7 Amy Muller danced in the Black Maria on March 24, 1896. The black background and patch of sunlight from the opening in the roof were standard traits of Kinetoscope films.

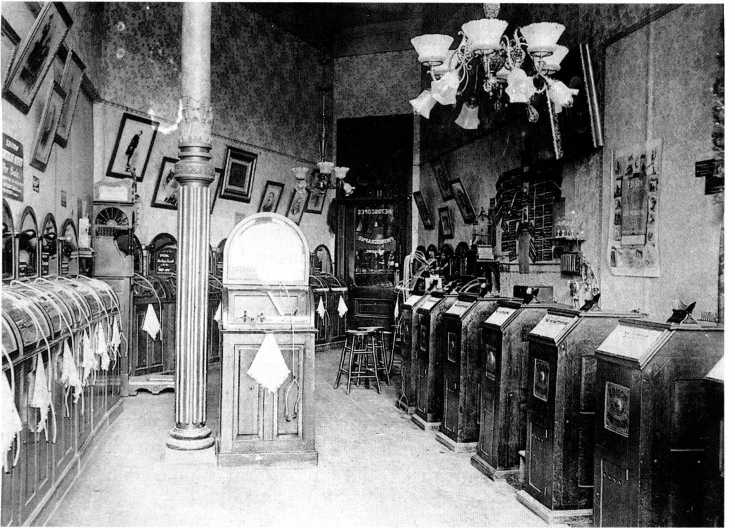

1.8 A typical entertainment parlor, with phonographs (note the dangling earphones) at left and center and a row of Kinetoscopes at the right.

Edison had exploited his phonograph by leasing it to special phonograph parlors, where the public paid a nickel to hear records through earphones. (Only in 1895 did phonographs become available for home use.) He did the same with the Kinetoscope. On April 14, 1894, the first Kinetoscope parlor opened in New York. Soon other parlors, both in the United States and abroad, exhibited the machines (1.8). For about two years the Kinetoscope was highly profitable, but it was eclipsed when other inventors, inspired by Edison’s new device, found ways to project films on a screen.

Tographic plates. In 1894, a local Kinetoscope exhibitor asked them to produce short films that would be cheaper than the ones sold by Edison. Soon they had designed an elegant little camera, the Cinematographe, which used 35mm film and an intermittent mechanism modeled on that of the sewing machine (1.9). The camera could serve as a printer when the positive copies were made. Then, mounted in front of a magic lantern, it formed part of the projector as well. One important decision the Lu-mieres made was to shoot their films at sixteen frames

1.9 Unlike many other early cameras, the Lumiere Cinematographe was small and portable. This 1930 photo shows Francis Doublier, one of the firm’s representatives who toured the world showing and making films during the 1890s, posing with his Cinematographe.

European Contributions Another early system for taking and projecting films was invented by the Germans Max and Emil Skladanowsky. Their Bioscop held two strips of film, each 3'/2 inches wide, running side by side; frames of each were projected alternately. The Skladanowsky brothers showed a fifteen-minute program at a large vaudeville theater in Berlin on November 1, 1895— nearly two months before the famous Lumiere screening at the Grand Cafe (see below). The Bioscop system was too cumbersome, however, and the Skladanowskys eventually adopted the standard 35mm, single-strip film used by more influential inventors. The brothers toured Europe through 1897, but they did not establish a stable production company.

The Lumiere brothers, Louis and Auguste, invented a projection system that helped make the cinema a commercially viable enterprise internationally. Their family company, Lumiere Freres, based in Lyon, France, was the biggest European manufacturer of pho-

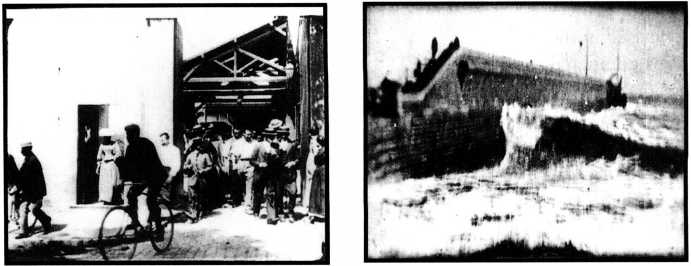

1.10, left The Lumiere brothers’ first film, Workers Leaving the Factory, was a single shot made outside their photographic factory. It embodied the essential appeal of the first films: realistic movement of actual people.

1.11, right Birr Acres’s Rough Sea at Dover, one of the earliest English films, showed large waves crashing against a seawall.

Per second (rather than the forty-six frames per second used by Edison); this rate became the standard international film speed for about twenty-five years. The first film made with this system was Workers Leaving the Factory, apparently shot in March 1895 (1.10). It was shown in public at a meeting of the Societe d’Encouragement a I’Industrie Nationale in Paris on March 22. Six further showings to scientific and commercial groups followed, including additional films shot by Louis.

On December 28, 1895, one of the most famous film screenings in history took place. The location was a room in the Grand Cafe in Paris. In those days, cafes were gathering spots where people sipped coffee, read newspapers, and were entertained by singers and other performers. That evening, fashionable patrons paid a franc to see a twenty-five minute program of ten films, about a minute each. Among the films shown were a close view of Auguste Lumiere and his wife feeding their baby, a staged comic scene of a boy stepping on a hose to cause a puzzled gardener to squirt himself (later named Arroseur ar-rose, or “The Waterer Watered”), and a shot of the sea.

Although the first shows did moderate business, within weeks the Lumieres were offering twenty shows a day, with long lines of spectators waiting to get in. They moved quickly to exploit this success, sending representatives all over the world to show and make more short films.

At the same time that the Lumiere brothers were developing their system, a parallel process of invention was going on in England. The Edison Kinetoscope had premiered in London in October 1894, and the parlor that displayed the machines did so well that it asked R. W. Paul, a producer of photographic equipment, to make some extra machines for it. For reasons that are still not clear, Edison had not patented the Kinetoscope outside the United States, so Paul was free to sell copies to anyone who wanted them. Since Edison would supply films only to exhibitors who had leased his own machines, Paul also had to invent a camera and make films to go with his duplicate Kinetoscopes.

By March 1895, Paul and his partner, Birt Acres, had a functional camera, which they based partly on the one Marey had made seven years earlier for analyzing motion. Acres shot thirteen films during the first half of the year, but the partnership broke up. Paul went on improving the camera, aiming to serve the Kinetoscope market, while Acres concentrated on creating a projector. On January 14, 1896, Acres showed some of his films to the Royal Photographic Society. Among these was Rough Sea at Dover (1.11), which would become one of the most popular first films. Seeing such one-shot films of simple actions or landscapes today, we can hardly grasp how impressive they were to audiences who had never seen moving photographic images. A contemporary review of Acres’s Royal Photographic Society program hints, however, at their appeal:

The most successful effect, and one which called forth rounds of applause from the usually placid members of the “Royal,” was a reproduction of a number of breaking waves, which may be seen to roll in from the sea, curl over against a jetty, and break into clouds of snowy spray that seemed to start from the screen.1

Acres gave other demonstrations, but he did not systematically exploit his projector and films.

Projected films were soon shown regularly in England, however. The Lumiere brothers sent a representative who opened a successful run of the Cinema-tographe in London on February 20, 1896, about a month after Acres’s first screening. Paul went on improving his camera and invented a projector, which he used in several theaters to show copies of the films Acres had shot the year before. Unlike other inventors, Paul sold his machines rather than leasing them. By doing so, he not only speeded up the spread of the film industry in Great Britain but also supplied filmmakers and exhibitors abroad who were unable to get other machines. Among them was one of the most important early directors, Georges Melies.

American Developments During this period, projection systems and cameras were also being devised in the United States. Three important rival groups competed to introduce a commercially successful system.

Woodville Latham and his sons Otway and Gray began work on a camera and projector in 1894 and were able to show one film to reporters on April 21, 1895. They even opened a small storefront theater in May, where their program ran for years. The projector did not attract much attention, because it cast only a dim image. The Latham group did make one considerable contribution to film technology, however. Most cameras and projectors could use only a short stretch of film, lasting less than three minutes, since the tension created by a longer, heavier roll would break the film. The Lathams added a simple loop to create slack and thus relieve the tension, allowing much longer films to be made. The Latham loop has been used in most cameras and projectors ever since. Indeed, so important was the technique that a patent involving it was to shake up the entire American film industry in 1912. An improved Latham projector was used by some exhibitors, but other systems able to cast brighter images gained greater success.

A second group of entrepreneurs, the partnership of C. Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat, first exhibited their Phantoscope projector at a commercial exposition in Atlanta in October 1895, showing Kinetoscope films. Partly due to competition from the Latham group and a Kinetoscope exhibitor, who also showed films at the exposition, and partly due to dim, unsteady projection, the Phantoscope attracted skimpy audiences. Later that year, Jenkins and Armat split up. Armat improved the projector, renamed it the Vitascope, and obtained backing from the entrepreneurial team of Norman Raff and Frank Gammon. Raff and Gammon were nervous about offending Edison, so in February they demonstrated the machine for him. Since the Kinetoscope’s initial popularity was fading, Edison agreed to manufacture Armat’s projector and supply films for it. For publicity purposes, it was marketed as “Edison’s Vita-scope,” even though he had had no hand in devising it.

The Vitascope’s public premiere was at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in New York on April 23, 1896. Six films were shown, five of them originally shot for the Kinetoscope; the sixth was Acres’s Rough Sea at Dover, which again was singled out for praise. The showing was a triumph, and although it was not the first time films had been projected commercially in the United States, it marked the beginning of projected movies as a viable industry there.

1.12 At the right, a Mutoscope, a penny-in-the-slot machine with a crank that turned a drum containing a series of photographs. The stand at the left shows the circular arrangement of the cards, each of which flipped down and was briefly held still to create the illusion of movement.

The third major early invention in the United States began as another peepshow device. In late 1894, Herman Casler patented the Mutoscope, a flip-card device (1.12). He needed a camera, however, and sought advice from his friend W. K. L. Dickson, who had terminated his working relationship with Edison. With other partners, they formed the American Mutoscope Company. By early 1896, Casler and Dickson had their camera, but the market for peepshow movies had declined, and they decided to concentrate on projection. Using several films made during that year, the American Mutoscope Company soon had programs playing theaters around the country and touring with vaudeville shows.

The camera and projector were unusual, employing 70mm film that yielded larger, sharper images. By 1897, American Mutoscope was the most popular film company in the country. That year the firm also began showing its films in penny arcades and other entertainment spots, using the Mutoscope. The simple card holder of the Mutoscope was less likely to break down than was the Kinetoscope, and American Mutoscope soon dominated the peepshow side of film exhibition as well. (Some Mutoscopes remained in use for decades.)

By 1897, the invention of the cinema was largely completed. There were two principal means of exhibition: peepshow devices for individual viewers and projection systems for audiences. Typically, projectors used 35 mm film with sprocket holes of similar shape and placement, so most films could be shown on different brands of projectors. But what kinds of films were being made? Who was making them? How and where were people seeing them?

World History

World History