The roster of Florence’s guilds reveals the enormous importance of the textile and clothing trades.95 In the early fourteenth century, the Wool guild alone counted between 600 and 700 investor-entrepreneurs in 200-300 firms, and the industry employed at least 10,000 artisans and workers in the various phases of production. A significant percentage of the Calimala’s 200 members invested in the 20 firms that each year, according to Villani, imported 10,000 bolts of cloth, worth 300,000 florins, to be dyed and resold. Many, perhaps a majority, of the 500-600 members of Por Santa Maria were local cloth retailers, and a smaller number produced silk cloth. The 200 members of the Rigattieri bought and sold used cloth. Measured by the number of entrepreneurs and laborers, the manufacture and sale of textiles constituted Florence’s largest complex of economic activities. The non-textile sector of the clothing trades included the guilds of the furriers, whose 200 members produced and sold fur coats and linings; approximately seventy-five tanners who manufactured leather clothing among other products; and the shoemakers whose 1,550 members in the city (and another 1,300 in the contado) made and repaired footwear. Before the Black Death, over 3,000 of the city’s estimated 8,000 guildsmen were involved in one or another of these trades, whose combined workforce was approximately 15,000.

The manufacture of woolen cloth was the heart of the domestic economy. According to Villani (12.94), in 1300 some 300 firms annually produced over 100,000 bolts of cloth. By the 1330s, the number of firms had declined to 200, and annual production to between 70,000 and 80,000 bolts. But the average value of cloths doubled with respect to a generation earlier, because the industry now produced higher quality cloths from superior English wool. He estimated the total annual value of production in the 1330s at 1,200,000 florins, not including profits, and calculated that one third or more of this sum was paid out in wages that supported 30,000 persons. For 200 firms to produce 70,000 bolts of cloth, average annual production per firm would have had to be 350 bolts. Although evidence from after the Black Death points to considerably lower production levels (from 1355 to 1374 firms produced an average of between 122 and 140 bolts per year),5 in these same decades some firms produced 250 and more bolts and would have produced still more if the Wool guild, for reasons to be explored in due course, had not set a production ceiling of 220 bolts per firm. Buonaccorso Pitti, a member of one of the guild’s leading families, says that the woolen cloth operation of his father Neri (130674) produced 1,100 bolts each year.6 But it is unclear whether the measure of a bolt remained the same over this period. In Florence the panno or pezza was usually about 36 yards long, but throughout Europe and Italy it varied from 30 to 50 yards, and it is possible that the length changed over time even in one place.

There is another point of entry into the reliability of Villani’s figures, and that is his estimate of annual labor costs of 400,000 florins and his assertion that 30,000 persons (workers and their dependents) lived on this sum. These figures yield hypothetical annual per capita living costs among workers of 131/3 florins. In Florence, the value of luxury goods, property, and major commercial transactions was measured in gold florins, while workers’ wages were paid and goods bought and sold locally in silver soldi and denari: twelve denari made one soldo, and twenty soldi made one lira, which was a money of account, not an actual coin. There was no fixed exchange rate between florins and lire, and market fluctuations determined their relative value. When the 96 97 florin was first coined in 1252, it was introduced as equivalent in value to the lira and thus worth 20 soldi. But silver money steadily lost value against the florin, which was worth 34 soldi by 1280, 47 in 1300, 65 by 1320, held steady between 60 and 70 until the mid-1370s, and was worth between 70 and 80 from then until 1410.98 In the years to which Villani’s data refer, with the florin at 62 soldi, annual per capita living costs of 131/s florins were equivalent to 825 soldi, or 2.26 soldi per day. A comparison is possible with the 1380s, when actual daily living costs for unmarried workers were 3 soldi, or 1,095 per year, and 10 soldi for a family of five, or 2 soldi per day per person.99 Villani’s implied estimate for the 1330s, based on aggregate wages, is thus quite close to living costs fifty years later, which makes his assumptions concerning total labor costs and the number of persons supported by this sum certainly plausible. With 30,000 persons dependent on the wages paid by the industry, even just one worker per household of four yields 7,500 workers. But much of the spinning and weaving was done by women who worked to supplement their families’ incomes, and many households had two persons employed in one or another of the various stages of production. Adding the women spinners and weavers to the 7,500 household heads who worked in the industry, we easily arrive at a total workforce of 10,000 in an overall population of 120,000. To doubt Villani’s figures on production and employment requires an alternative explanation for this large population and for how all those people earned their living. The guild’s merchant-entrepreneurs found bigger profits in producing a smaller number of cloths of higher quality and value,100 thus presumably employing fewer workers by the 1330s than they had in 1300. But even with this possible decline in the number of workers, Florence remained heavily dependent on the woolen cloth industry. Assuming that at least half the population was of working age (in 1427, 55% was between the ages of 15 and 64101), 10,000 textile workers in a population of 120,000 means that about one of every six men and women of working age was employed in the manufacture of woolen cloth. And if we add the merchant owners, their bookkeepers, and agents, the proportion is still greater. The industry’s general prosperity in the fourteenth century helps to account for the growing population before the plague and its respectable recovery in the second half of the century. But when the industry shrank after 1400, Florence’s population sank to the lowest level in its entire history.

The entrepreneurs of the guild bought, imported, and kept ownership of both the wool and the cloth made from it throughout the complex production process, which alternated between workplaces owned by the entrepreneurs and the shops and homes of independent artisans. The initial stages of cleaning, sorting, beating, and combing the wool were performed in the owners’ workplaces by large crews of mostly unskilled wage-workers, later called Ciompi. Of the stages of this initial preparation of the wool, only the washing process took place in the shops of independent artisans. The wool was then distributed to spinners, including many women, most of whom worked at home. Agents representing the owners made regular rounds through working-class neighborhoods, delivered the wool and set rates of pay and completion schedules, and returned to collect the yarn and pay the spinners. The yarn in turn was distributed by agents to weavers, who worked either at home or in modest shops, and always for piece-rates. From the weavers the agents collected the bolts of cloth that were still in need of a whole series of finishing processes. The burling, washing, fulling, and stretching of the cloth occurred in large workplaces, some owned by the guild and some by individual entrepreneurs, whereas the dyeing, mending, napping, and pressing of the finished product were performed by artisans in their shops. Skilled artisans, especially dyers, often employed workers in shops of their own that required substantial investment. Among textile artisans the dyers were the wealthiest and potentially most independent. The industry was thus a complex mix of centralized workplaces, independent and occasionally well-to-do artisans like the dyers, poorer but still independent artisans like spinners and weavers who worked at home, and a mass of unskilled wage laborers in the shops of both owners and artisans. Tensions ran high in this most important of Florence’s industries, in part because the guild of owners denied to all these categories the right to form associations while at the same time claiming and exercising tight regulatory control and often punitive jurisdiction over them all.102

The construction industry was a major employer of labor and source of domestic wealth. In 1358 the guild of Maestri di pietra e legname (master masons, wallers, and carpenters) registered over 400 members in the city and 272 in the contado, a total of almost 700 a decade after the plague. A 1391 list records a total of 915, without distinguishing between city and contado. The Legnaiuoli, woodworkers and cabinetmakers, numbered 200 in 1391. An industry that counted between 900 and 1,100 enrolled guildsmen after the plague may very well have had twice that number before it and an equal number of unskilled laborers and apprentices. The largest among the many early fourteenth-century building projects were the city walls and the new cathedral. Begun in the mid-1290s, the construction of the cathedral was entrusted in 1331 to the Wool guild, as was the Campanile, or bell tower, in 1334. Designated percentages of treasury payments and receipts of indirect taxes were assigned to fund construction. A communal audit of 1359 revealed that in the preceding twenty-six years the cathedral project’s total income amounted to over 300,000 lire (almost 95,000 florins).103 From 1333 to 1348, the 127,500 lire spent at the cathedral works would have paid a year’s living costs for over 3,000 people. By the 1370s and 1380s government subsidies to the cathedral reached 3 to 31/3 percent of ordinary revenues.104 The workforce varied with the seasons and stages of construction: between 1375 and 1378 (and this was during a war) the total of skilled and unskilled workers at the project each month ranged from 80 to 225 (and more often than not was over 200, but some part-time), including between 40 and 140 masons.105 Whereas the Campanile was built fairly quickly between 1334 and 1357,106 the construction of the cathedral continued, with many and sometimes long interruptions, until the 1420s when, with the church otherwise complete, there remained the great task of building the dome (see Plate 2).

The first four gates of the new circuit of walls were erected in 1284-5, but work was interrupted until 1299 and again in 1304. Construction resumed in 1310 and continued until the walls were completed in 1334. Between 1313 and 1329 at least 170 masons and master wallers were employed, and no doubt hundreds of workers who hauled the massive amounts of stone needed for the more than five-mile circuit of walls with their seventy-three towers spaced every 380 feet, many of them more than 130 feet tall, as well as the wood for fifteen huge gates (see Plates 3 and 4). Construction was financed initially by the requirement that every will include a bequest for the walls, and then by periodic subsidies from the commune, assignments from tax revenues, and forced contributions from the clergy. In one particularly intense six-month period of work in 1323, the treasurers of the Officials of the Walls recorded spending 14,000 lire.107 During these same decades major construction sites existed all over the city. Additions to the former palace of the primo popolo (the Bargello) continued into the 1320s, even as the palazzo of the second

Plate 2 The Cathedral-Baptistery complex. Left to right: Baptistery of San Giovanni (begun in eleventh century); Bell Tower (“Campanile,” 1334-57, original design by Giotto); Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (known as the “Duomo,” begun in mid-1290s, original plan by Arnolfo di Cambio, and dome by Filippo Brunelleschi, 1420-36) (Alinari/Art Resource, NY)

Popolo was under construction. The hospital of Santa Maria Nuova was begun in 1286. The Dominican basilica of Santa Maria Novella was built between 1280 and 1360, and the Franciscans built Santa Croce from 1295 until well into the fifteenth century. The granary-oratory of Orsanmichele was rebuilt in the late 1330s. And the middle and later part of the century saw the construction of the loggia of the confraternity of the Bigallo in 1352-8, the loggia of the priors (later called the Loggia dei Lanzi) in 1374-81, and the palace of the Mercanzia, begun in 1359.

Public and ecclesiastical projects were only one part of the building boom of the early fourteenth century. The great fire of 1304 necessitated a general rebuilding that lasted many years. Until then, much of Florence had been built in wood (not the palaces and towers of the elite families, but the humbler homes and shops of artisans and workers). After the fire the city was rebuilt

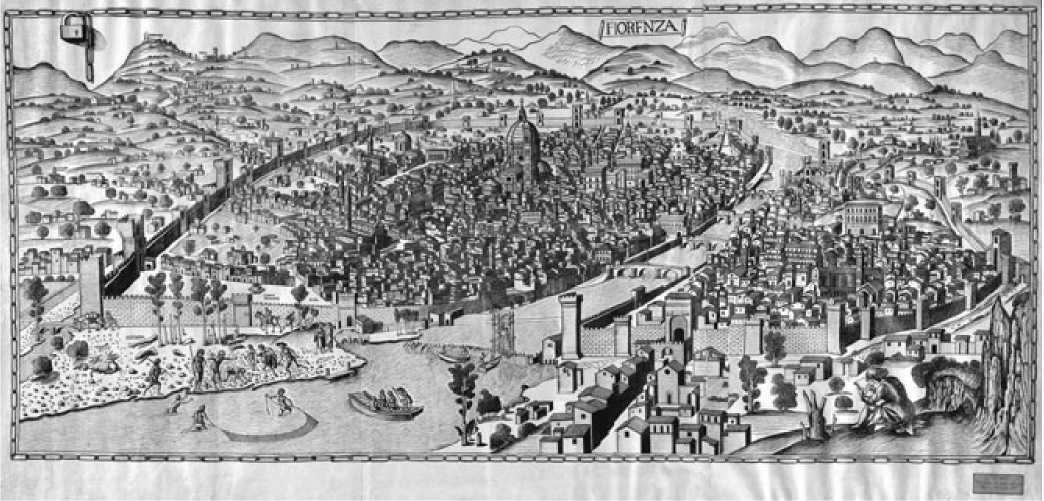

Plate 3 Florence c.1480: The “Catena map,” woodcut, showing the city enclosed by the third circuit of walls completed in 1334, with gates and towers (Scala/Art Resource, NY)

Plate 4 Porta Romana, the southernmost gate of the third set of walls (Alinari/Art Resource, NY)

Largely in stone, which took longer and cost more. There is no way of knowing how many masons worked on such projects, nor how many laborers they employed. In the fifteenth century, master wallers typically organized and supervised small crews that included an assistant and one or two wageearning laborers.108 Some indication of the ratio of skilled wallers to unskilled laborers emerges from the building records of Santa Maria Nuova, where approximately 130 laborers were employed between 1350 and 1380, and 108 master masons between 1358 and 1380.109 If we conservatively estimate 1,500 masons, wallers, and carpenters before the plague and at least an equivalent number of non-skilled workers and apprentices, the total work force in the building industry could easily have exceeded 3,000.

Another look at the list of guilds reveals the prominence of the cluster of trades that provided food and drink to the city’s population. Four guilds were

Involved in provisioning: the butchers; sellers of cured meats and fish, oil, and cheese; wine retailers; and bakers. Before the plague, these guilds had a total of approximately 1,000 members in the city, many with assistants, apprentices, or hired workers. In 1330 the butchers had 330 members in the city and another 189 registered in the contado. Villani’s statistics on the annual consumption of meat in the city help to account for the size and stature of this guild, which alone among the provisioning trades ranked among the top twelve guilds. Each year, he says, the city consumed 4,000 cattle and calves, 60,000 sheep, 20,000 goats, and 30,000 hogs, a total of 114,000 animals, which probably yielded some 7,000,000 pounds of edible meat, or 64 pounds per person for the population over the age of three (110,000), and in reality more than that since some religious ate no meat. Moreover, the number of days in which the consumption of meat was prohibited for the laity as well (Fridays, Saturdays, and all of Lent, altogether about 140 days) means that on days when meat was eaten the average daily per capita ration was more than a quarter of a pound. The wealthy no doubt ate more than the poor, but meat of one sort or another (and Villani says nothing of chicken or fish) was part of the daily diet of the vast majority of Florentines, laborers and the working poor included.19 After the plague, the number of butchers declined in rough proportion to the population: 156 in the city and 45 in the contado in 1352, but by the century’s end contado membership climbed back to 179.

The guild of retail wine sellers counted 92 members in 1336. Curiously, it slightly increased in size after the Black Death, with 105 members in 1353. Villani says that in the mid-1330s between 55,000 and 65,000 cogna of wine were sold each year in the city. Taking 60,000 as the average for these years, this yields a total consumption of between 24 and 27 million liters (opinions differ about the size of a cogno),20 or somewhere between 200 and 225 liters per person. If we assume that children drank less than adults (and infants not at all), the annual per capita consumption among adults was perhaps close to 300 liters. The retail sale of wine was clearly a big business, especially since this huge amount was sold by only 100 dealers, who on average must each have handled 250,000 liters per year. Because the price of wine varied considerably, it is difficult to estimate the total value of sales. In the 1330s the price per cogno varied between 8 and 12 lire; if 10 lire was the average price, the annual value would have been 600,000 lire (at the time, 185,000 florins). In the second half of the century, the price of wine was 21/2 times higher, which means that, if per capita consumption remained steady in a population smaller by half, the total value of sales actually increased to 750,000 lire. 110 111

In the early fourteenth century the guild of Pizzicagnoli e Oliandoli, who, in addition to oil, cheese, and cured meats, sold fruit, nuts and a long list of other foods, increased its city membership from 200 to over 400, including many women. The only datum Villani gives for consumption in this sector is the 400 wagonloads of melons that he says entered the city each day every July. Even if each wagonload contained only 125 melons and deliveries were made on only 20 days of the month, the resulting 8,000 deliveries would have supplied a million fresh melons to the city every July.

Bread was of course the heart of the pre-modern diet. The guild of bakers had 174 members in 1337 and 243 in 1347, including 40 women. Villani, who counted 146 bakers in the mid-1330s, says that the city consumed 140 moggia of grain every day, compared to 800 per week, hence 114 per day, in 1280: a 23% increase that matches the population growth. A moggio was equivalent to 420 kilograms, or 924 pounds. This yields total daily consumption in the 1330s of almost 59,000 kg, or 130,000 pounds, equivalent to over a pound of bread per person per day. Assessing the economic significance of grain transactions is complicated by the wildly fluctuating prices caused by uneven harvests and the government’s policy in times of scarcity of buying grain and selling it below cost. Despite the productivity of the contado, which in good years produced 80% of the 150,000 moggia needed to feed itself and the city, and the ample supplies imported from southern Italy, it was impossible to prevent periods of short-term scarcity and skyrocketing prices. Between 1320 and 1335, the average price per staio (one twenty-fourth of a moggio) ranged from a low of 71/2 soldi in 1321 to a high of 30 in the year of greatest scarcity, 1329, when the government purchased grain below the market price and distributed it at no cost to charitable organizations.21 The total value of grain sales could thus be very different from one year to the next. In the “normal” years of the early and mid-1320s, the average cost was 121/2 soldi per staio, which means that the roughly 1,225,000 staia of grain (140 x 365 x 24) sold each year cost Florentine consumers approximately 765,000 lire, or 235,000 florins. After the crisis years of 1328-30, prices returned to a high normal of 16 soldi in 1331-5, and, assuming consumption at normal levels, total grain sales would have been worth 980,000 lire, or 300,000 florins in each of these years.

World History

World History