The belief structure of early human society is usually summarized by the term “animism" which means that people did not yet conceive of deities in the modern sense, but saw nature and even themselves as a composite of thousands of overlaid and often competing life forces of different scales and potencies. The term “animism” derives from the Latin word “anima” and implies an indwelling life force that one could also conceive of as “soul.” It is of course a modern term coined in the nineteenth century. Even so, explaining animism is not easy since it is often seen simply as nature-worship. This could lead to a misleading oversimplification. Nature, as we perceive it, differs from society, and indeed it stands in sharp contrast to it, while in these ancient times it was a continuum in which a person was included, rather than to which he or she was opposed. But the range of intensities about this relationship can vary. The Hazda, who live in Tanzania, and the Haida in northwest Canada are on the extreme ends of this difference. The Hazda, like the! Kung, are quite informal in their relationship to death. A dead person is placed in his thatch hut, which is brought down on him and burnt. The Haida, by way of contrast, have mythologies filled with powerful animals, and in death the clan will host elaborate feasts. This seems to imply that early human society, as it moved eastward from Africa, became more complex and ritualistic.

And yet in both the Hazda and the Haida, death is not a finality, but a transition into the world of spirits. The native people of Australia, for example, see themselves as part of a world full of interconnected forces that can transition into a rock or a large tree. They themselves are imbued with kuranita (life essences) that form a continuum of beneficent energies. At certain times, groups of hunters will assemble at specific markers in the landscape such as a “kangaroo stone,” for example, and by means of songs and rituals, or sometimes a ground drawing, conjure up the life essences of kangaroos so they can reenter the living sphere.55 This is often achieved by inducing dreaming. Indeed, a dream abolishes the barriers between the past, the present, and the future so that time is experienced as a sort of simultaneity in a timeless space.

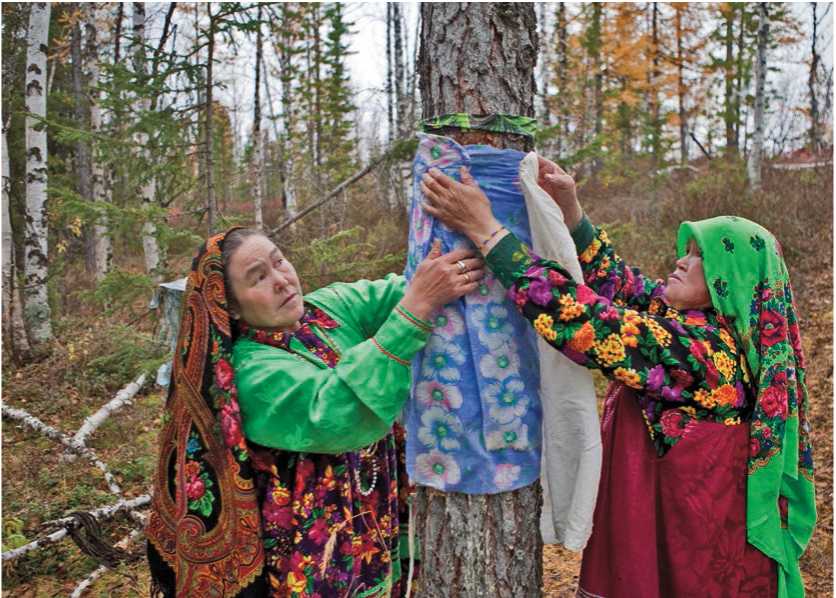

Geographical features such as certain mountains may be also endowed with a magical aura (Figures 1.36 and 1.37). Ancient Indian

Figure 1.37: A Khanty women and her friend tying material around a sacred tree to protect her youngest son, Yamal, Western Siberia, Russia. Source: B & C Alexander/ ArcticPhoto

Texts from between 500 bce and 400 ce speak about elaborate mountain top rituals and thus give evidence of the astonishing longevity of these devotional practices. The people of the Surasena Kingdom, for example, worshipped the Govardhana Mountain (located near the town of Vrindavan in India), circulating around the base of the hill whilst praying and singing.56

Similarly, the Inca visualized that each mountain had its own indwelling spirit, or apu, the most important ones of which required offerings of sacrifices to the mountain spirit. Some rocks and caves also are credited as having their own apu. The best-known sacred mountain today is Mount Fuji, at the base of which is the sacred forest Aokigahara, or the Sea of Trees (Figure 1.38). The mossy ground is uneven, broken up by the numerous earthquakes. In some place the trees are so thick that it is not hard to find places completely surrounded by darkness. Mist often hangs over the slope. Folk tales and legends tell of demons and spirits that haunt the area. Mount Misen is another sacred mountain in Japan, sitting midway along a route often traversed by followers of Shugendo, who practice an ascetic lifestyle. The area often resounds even today with the blasts of trumpet shells energetically blown by those participating in ritual exercises.57

Peak sanctuaries, and more specifically peaks together with caves, were at the heart of Mi-noan religious practices on Crete. Three caves were particularly important: the Dictaean Cave on Mount Dicte near the village Psychro, the Idaean Cave on Mount Ida near Anogheia, and the Cave of Eileithyia, dedicated to the birth goddess. The Dictaean Cave, cold and moist even in the heat of summer, with a pool of water surrounded by stalactites, was the site of rituals dating back to the earliest time of Cretan habitation. The Cave of Eileithyia is now a Christian site and is still visited by Cretan women. The cave most intimately connected with the Cretan creation myth is the cave on Mount Ida, where the earth mother Rhea gave birth to Zeus. Myth describes him as tended by nymphs and protected by youths against his father, the legendary Chronos. Zeus then fathered Minos, who became King of Knossos and of Crete (Figure 1.39). A proces-

Figure 1.38: Aokigahara, “Sea of Trees,” Yamanashi, Japan. Source: Takeshi Akamatsu

Figure 1.39: Psychro Cave, Crete. Source: © Jerzy Stzelecki (Http://creativecom-mons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ deed. en)

Sion led up to the peak of the mountain to a special sanctuary where offerings were “fed” into a cleft in the rocks. Still today an annual procession makes its way up to the top of the mountain for the feast of Afendis Christos—an instance where Christianity tried to nullify “heathen” cults by appropriating ancient rituals and customs.

World History

World History