Their wool is rough and thin at the ends, and from it they weave the thick sagi [coats] which they call laenae; but the Romans have succeeded even in the more northerly parts in raising flocks of sheep (clothing them in sheepskin) with a fairly fine wool.122

So wrote Strabo of wool production in Celtic Gaul. There is no doubt that the raising of sheep for wool was an important aspect of the Iron Age economy. Unlike milk, wool production is not dependent on either the age or sex of the animal. The faunal evidence indicates that large numbers of sheep were kept for wool and only killed for food long after the optimum time for meat had passed.123 In any case, compared to cattle and pigs, the meat yield of sheep is small. Wool production continued to be important during the Roman period.124 Strabo comments upon the fame of Gaulish and British woollen blankets, and the Emperor Diocletian, at the end of the third century AD, levied a huge tax on the birrus Britannicus, a kind of woollen duffel-coat, and the tapete Britannicum, a rug used on saddles and couches.125

There must have been a well-organized wool-cloth industry during the Iron Age. Flocks would have been carefully managed and their size may have been strictly controlled. If an inhibition on mating was deemed desirable, the sexes could be separated by means of corralling or the rams could be fitted with an apron-like device to stop them from serving the ewes.126

If we assume that Iron Age sheep were basically of Soay type, then their wool could have been gathered either by plucking or by shearing.

Soays shed naturally during June, so, if they were plucking wool, the farmers would have needed to gauge the best time to gather it, just before it was rubbed off naturally.127 One sheep would produce only about 1kg of wool in a year, and a small family of two adults and three children might need as many as twenty Soay sheep to keep themselves in clothes and blankets.128 Barry Cunliffe suggests that the sheep may have been plucked with the bone combs which are so common on Iron Age sites and which are generally designated 'weaving combs'.129 During the Iron Age there was an important technological advance in wool-winning with the invention of iron shears, which meant that the entire fleece could be removed and the farmers no longer needed to rely on the somewhat haphazard business of plucking during the annual summer moult. Shears are common on Continental Iron Age sites130 but may not have been introduced into Britain until the Roman period.

To the Romans, Celtic wool was rough and coarse, but Diodorus Siculus mentions variegated colours, which could have been natural or dyed.131 Soays are brown and white, but selected breeding may have produced particular colour traits. Very few remains of Celtic fleeces or wool are known archaeologically, but a complete fleece (arguing the use of shears) was found at Hallstatt in Austria, and a bog in north Germany has produced another, dating to around 500 BC. Wool fibres were embedded in the bronze of a funerary couch at the tomb of the Hallstatt prince at

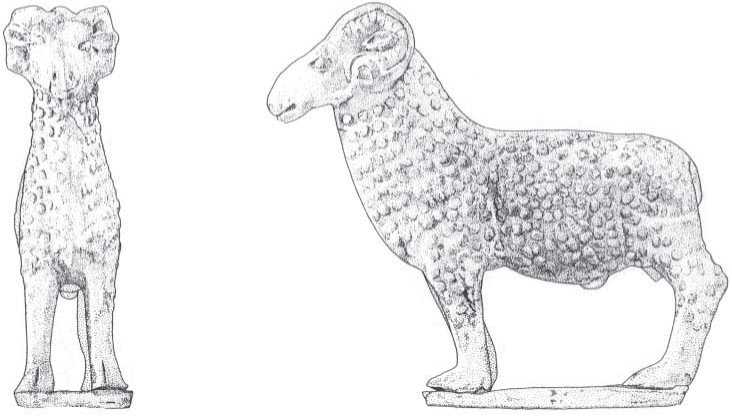

Figure 2.20 Clay ram figurine, found with the burial of a Romano-British infant, at Arrington, Cambridgeshire. By courtesy of Cambridgeshire County Council.

Hochdorf in Germany.132 The wool would have been hairy and relatively stiff, but some finer wool could have been produced by controlled breeding.133 Soays have medium-heavy kemp hairs and a finer underwool; sheared fleeces result in a mixture of the coarse kemp hairs and the fine, soft underwool. Interestingly, although the texture of wool possibly did improve during the Roman period, some yarn which survives from the Roman fort of Vindolanda in north Britain, with its exceptional waterlogged preservation of organic remains, shows that the same hairy fibre was sometimes still being used.134

The shed wool of naturally moulting sheep probably led to the accidental discovery of both felting and spinning in antiquity: the wool would be rubbed off onto bushes by sheep and this process might sometimes have led to the winding of the discarded wool into long strands. Once the sheep had been plucked or sheared, the wool was cleaned and carded with bone or antler combs: the act of combing would ensure that the fibres lay straight. After that the wool was ready to be spun: spindle-whorls and bobbins survive on many Iron Age sites, including Glastonbury, which produced a great deal of evidence for wool production.135 The yarn was then woven into cloth on a vertical loom: weaving involves the interleaving of horizontal weft yarns over and under the stronger, vertical warp threads. The loom itself is merely a frame on which the warp yarn can be held taut.136 Loom-weights of clay or stone are common finds. Sites like Glastonbury have revealed evidence for all the stages of cloth-making: combs, spindle-whorls, bobbins and loom-weights.137

World History

World History

![The General Who Never Lost a Battle [History of the Second World War 29]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581983_1425486253_part-29.jpeg)