Well, if she gets insulted just because I insulted her!

Groucho Marx

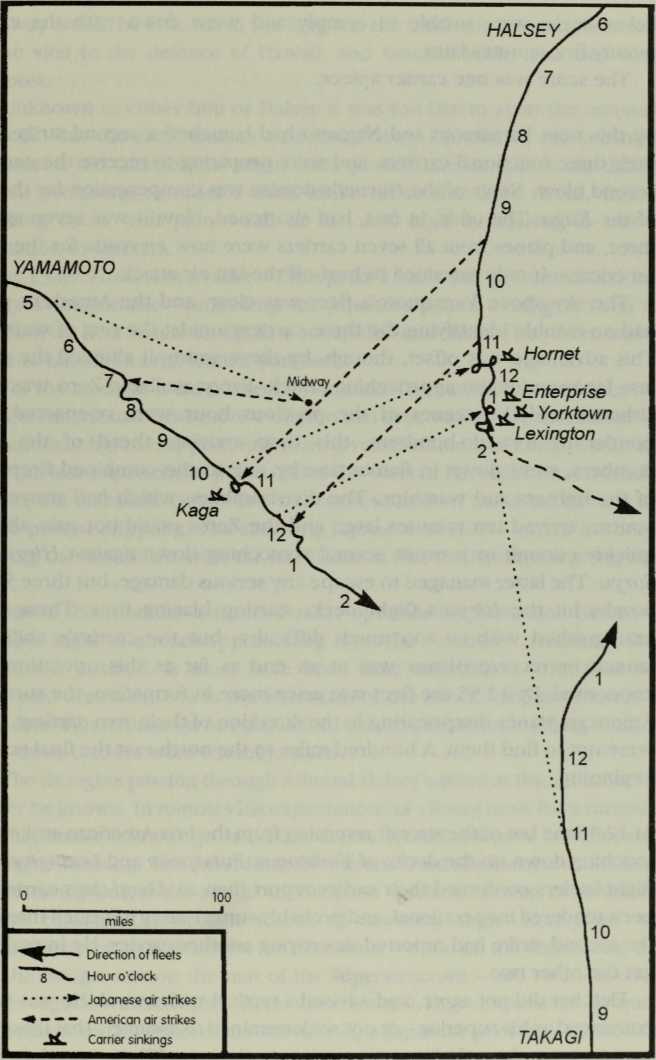

In the distant Pacific the two warring navies prepared for what both believed would be the decisive confrontation. In Hiroshima Bay the Japanese admirals bent over maps in the Yamato operations room, and worked out the details of Kuroshima’s new plan. Haste was the order of the day.

It was a brilliant plan, which for sheer lethal simplicity could only be compared to Manstein’s plan for the invasion of France. It is one of the great ironies of the Second World War that both were second-best plans, only adopted when details of the preferred plans became known to the enemy. Both plans also made use of this fact, of the enemy ‘not knowing that we knew that he knew’. Both were the product of a gifted professional strategist’s dissatisfaction with the predictability of a tradition-bound plan. Both were cast to give full rein to the revolutionary possibilities inherent in new weaponry by men not professionally associated with those weapons. Kuroshima was no more a ‘carrier man’ than Manstein was a ‘panzer man’, but both had received support from those who were associated with the new weaponry, in the one case Yamaguchi and Genda, in the other Guderian.

There were also differences of emphasis. Kuroshima’s plan perhaps relied more on the ‘double-bluff aspect. The original plan would serve as a feint for the new one, and to this end the broken code was continued in use throughout the month of May. Naturally the information transmitted was somewhat selective. Kuroshima knew that the Americans would expect Nagumo’s carriers north-east of Midway, and it was intended to satisfy this

Expectation. This time, however, the main battle-fleet would be in close attendance. The Americans would also expect a diversion in the Aleutians and a convey of troopships for the seizure of Midway. Both of these would certainly be at sea, but the first without the carriers Junyo and Ryujo and with severely limited objectives, the second with orders to assault the island only after the decisive naval engagement had been fought.

On the other hand, the Americans would not be expecting Nagumo to take his carriers south of Midway Island, in the general direction of the Hawaiian group. This would pull the American carriers south, towards the greatest surprise of all, a second carrier force under Vice-Admiral Takagi moving northwards on an interception course in complete radio silence. If, as seemed possible to Kuroshima, the American carriers retreated to the east rather than seek battle with Nagumo’s powerful force, then Takagi’s force would be in position to cut them off. Whatever happened the US carriers would find themselves outnumbered and outmanoeuvred, and swiftly dispatched to the ocean floor. And then nothing would stand between the Imperial Navy and the West Coast of America but a few planes on Oahu and a bevy of obsolete battleships in San Francisco Bay.

If Yamamoto’s haste was one side of the Pacific coin, an American need to temporise was the other. The ‘Two-Ocean Navy’ programme, which was designed to give the US Navy preponderance in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, had only been set in motion in late 1940, and the first of the new ships would not be leaving the stocks until the coming autumn. For the next six-nine months the new Pacific C-in-C, Admiral Chester Nimitz, would have to hold off the Japanese with what he had. If he could do so - hold Hawaii and its Midway sentry, keep open the route to Australia - then the balance would begin to swing faster and faster in America’s favour. But it would not be easy.

The Japanese preponderance in all classes of warships has already been noted; the American admirals were as aware of this basic fact as the Japanese themselves. The American public - or, to be more precise, the American press - was a different proposition. The pre-declaration of war attack on Port Arthur in 1904 might have been greeted by the American press as a ‘brilliant and bold seizure of the initiative’, but the identical attack on Pearl Harbor had not been viewed quite so magnanimously. It had been a ‘Day of Infamy’ and infamy, as all lovers of Hollywood films will know, is always the work of the weak and the cowardly. The Great American Public clamoured for some decisive punitive action against these insolent little yellow men.

Though most of the US naval chiefs were obviously aware that these ‘little yellow men’ were travelling around in some very large warships it is hard to avoid the conclusion that at some level they shared the public underestimation of Japanese capabilities. The admirals were worried, but they were not as worried as they should have been. Nimitz’s instructions to his carrier admirals on the eve of battle were cautious enough:

... you will be governed by the principles of calculated risk, which you shall interpret to mean avoidance of exposure of your forces to attack by superior enemy forces without good prospect of inflicting, as a result of such exposure, greater damage on the enemy.

- but the mere fact of sending four carriers against an enemy force probably comprising twice that number made a mockery of such caution, and suggested a gross American optimism as regards the quality of the Japanese ships and crews, and the brains that directed them. Nimitz should have known better.

There was one mitigating circumstance. In August 1940, after eighteen months of solid work. Colonel William Friedman had broken the Japanese naval code. The code-book at the bottom of Darwin harbour, which Yorinaga had assumed to be the source of this iUicit knowledge, had merely confirmed Friedman’s findings. The belief that they ‘had the drop’ on the Japanese provided Nimitz and his colleagues with an enormous fund of false confidence.

The Japanese did not disabuse them, and no suspicions were aroused when messages advancing Operation ‘AF’ by seven days were deciphered by the Black Chamber Intelligence Unit at Pearl Harbor.

But this change of date did necessitate a change in American plans. Task Force 16, centred round the carriers Hornet and Enterprise, had not yet returned to Pearl Harbor from its abortive mission to the Coral Sea. Now it would not have time to do so, and for one person this was indeed good news. Admiral William ‘Bull’ Halsey, the senior American carrier admiral, had a debilitating skin disease and was due for hospitalisation when the Task Force reached home. But now the bed and lotions would have to wait, and Halsey would have the chance to do what he had been itching to do since the attack on Pearl Harbor, to ‘chew Yamamoto’s ass’.

Similar sentiments, and a similar over-confidence, were also much in evidence as Rear-Admiral Frank Fletcher led the other Task Force (17, comprising the carriers Lexington and Yorktown with cruiser and destroyer support) out to sea on 23 May. Sailors and fliers were buoyant.

Eager to get a crack at the despised enemy. Only their commander seemed subdued, and after the war he would explain why:

There seemed to be a general consensus throughout the fleet that we were some kind of St George sallying forth to slay a particularly nasty dragon. I couldn’t escape the feeling that if St George had been half as confident as most of my staff and crews then the dragon would probably have won.

The dragon was already at sea. On 20 May Vice-Admiral Takagi had sailed from Truk in the Carolines with his four carriers - Shokaku, Zuikaku, Junyo and Ryujo - and a strong battleship, cruiser and destroyer escort. The same day the Midway assault force had left Saipan, accompanied by four heavy cruisers. On 21 May Yamamoto’s Main Fleet had upped anchor in Hiroshima Bay and threaded its way in single file down the Bungo Channel to the ocean. The Commander-in-Chief, as addicted to the / Cbing as he was to poker, had thrown the yarrow stalks on the eve of departure. The hexagram had been Hsieh, ‘deliverance’. ‘Deliverance means release from tension... his return brings good fortune because he wins the central position.’

II

Some six days later, at 4.15am on 28 May, Yamamoto’s fleet sailed out from under the clouds two hundred miles west-north-west of Midway Island. Light was already seeping across the horizon, the stars fading in the sky above. The commander himself, gazing out from the bridge of the Yamato, saw the new day uncover his vast armada of ships. Behind the Yamato, their guns bristling, rode the battleships Nagato and Mutsu; two miles or so to the north another four battleships sailed on a parallel course. Between these two lines of firepower the four carriers under Admiral Nagumo - Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu - formed a wide rectangle. Across the water their gongs could be heard vibrating, signalling the order to bring the first wave of planes up on to the flight deck. Soon the green lights would be glowing, and the first Zero fighters would take to the sky, there to hover protectively over the launching of the bombers. All around the capital ships a screen of destroyers, augmented to the van and rear by cruisers, kept a wary eye out for enemy submarines. This was the day of reckoning, Japan’s chance to win control of the Pacific, to prolong the war beyond the limits of American patience or resolve.

By 05.15 the torpedo-bombers (‘Kates’) and dive-bombers (‘Vais’) had formed up in the sky overhead and, surrounded by their Zero escort, disappeared in the direction of Midway. Having launched his bait Yamamoto set out to find his prey. Search planes from the cruisers and carriers were sent out to cover a three hundred-mile arc to the east. In the meantime more fighters were sent aloft to shield the fleet, and Yamamoto settled down to wait for news of the enemy.

240 miles due north-east of Midway the two American Task Forces waited under a clear blue sky. Halsey, with nothing as yet to attack, had only launched his search planes, some two hours earlier, at first light. The Admiral, according to one of Enterprise's few survivors, was as tense as ever on the eve of action, pacing up and down the bridge, cracking nervous jokes about Japanese incompetence. He knew Yamamoto was out there somewhere; he just wanted a precise fix, and then the world would see how the Japanese would fare in a straight fight. Certainly they were past masters at backstabbing, but, he insisted to his staff, once confronted by a resolute enemy they would find they had met their match. One is irresistibly reminded of the late George Armstrong Custer, riding contemptuously into a Sioux and Cheyenne camp whose warriors outnumbered his own by twenty to one. On seeing the huge encampment Custer is said to have exclaimed: ‘Custer’s luck! We’ve got them this time!’

Halsey might well have echoed the sentiment at 06.05, as a message came through from Midway Island. The radar there had picked up the incoming Japanese strike force some thirty miles out. Five minutes later Halsey got his precise fix. One of the Yorktown dive-bombers launched on search duty had found the Japanese Fleet, 135 miles west-north-west of Midway, pursuing a south-easterly course. The Admiral signalled to his own fieet: south-south-west at full speed. Within three hours he should be close enough to launch a strike.

On Midway Island the American offensive air-strength - Dauntless and Vindicator bombers. Marauders and Avenger torpedo-bombers, high-level B-17 ‘Fortresses’ - had scrambled off the island airstrips and into the sky, setting course for the probable location of the Japanese Fleet. They went without fighter protection; the obsolete Buffalo Brewsters neither possessed the necessary range nor could be spared from the duty of defending the island.

At 06.40 the Japanese planes appeared out of the west, a dark mass of bombers crowned by a misty halo of Zeros. The Buffaloes attempted to

Intercept the bombers but were cut to ribbons by the fighters; of sixteen flown up only two returned to crash-land in the lagoon. Fuchida led his planes down against the island’s installations, into the teeth of spirited American anti-aircraft fire. The fuel installations went up in a sheet of flames, blockhouses disintegrated under a hail of bombs. Most successful from the Japanese point of view, the runways were cratered from end to end. No American planes would be launched from Midway in the near future. The cost was five Kates, three Vais, and a solitary Zero.

150 miles away the motley armada of American planes from the island was approaching Yamamoto’s ships. Unfortunately the little cohesion it had once possessed was already a thing of the past, the attack arriving in driblets that the Japanese could fend off without undue exertion. First the torpedo-bombers, coming in low, were subjected to a vicious enfilade from the ships screening the precious carriers and the close attentions of the Zero standing patrol. Only two limped back to Midway, where the lack of a functional airstrip necessitated more crash-landings in the lagoon. Next the dive-bombers arrived, and these too found the defences hard to penetrate, only three piercing through the flak and fighters to unleash their bombs. All three, by accident or design, chose Soryu as their target, but drenched decks from three near-misses was the only outcome. The B-17s fared no better, dropping their bombs with great enthusiasm but little accuracy on the twisting ships 20,000 feet below. Optimistic American eyes counted many hits; there were none. The Japanese Fleet had absorbed all that Midway could throw at it, without so much as a scratch.

It was 07.25. From the Yamato's bridge Yamamoto watched his fleet repairing the damage done to its formation. Fuchida had just radioed news of the Midway attack, advising that there was no need for a second attack. The airstrip was out of operation, the Japanese could concentrate on the American carriers they hoped were some 300 miles away to the north-east. Accordingly Yamamoto ordered Nagumo to send the second wave of bombers back below. Barring a calamity there would be time to bring in the returning first strike while the Americans were still out of range. Reinforcements were sent up to join the Zero patrols above the fleet. And then, again, a period of waiting.

By 08.20 Fuchida’s planes were setting down on the flight decks, and being rushed below for re-arming and refuelling. Simultaneously the second wave was brought up from the hangar decks, already primed for action against the American Fleet. By 09 00 the process had been completed without any ominous sighting of approaching American planes. There was still no word of the enemy carriers. The search planes should be on the

Return leg of their sweeps by this time. If the Americans were where they should be, then they would soon be sighted. Either that or things were not working out according to plan. And that would entail some radical rethinking on the Yamato bridge.

It did not prove necessary. At 09.24 a report came in from the Akagi scout plane - ‘a large enemy force’. Ten minutes later came the composition. The force included four carriers, and was steaming south-westward some 120 miles north-east of Midway.

This was it! Kido Butafs planes swept down the flight decks and into the air. This second wave was mostly composed of Pearl Harbor veterans who had been deliberately held back by Nagumo and Genda for this moment. It was the cream of the Navy air arm. Soon over a hundred planes - roughly equal numbers of Vais, Kates and Zeros - were forming up overhead, and soon after 10.00 the order was given by flight-leader Egusa to proceed northeast against the enemy. Twenty of the Zeros remained behind, hovering above the Japanese carriers. Yamamoto did not want Nagumo to take any unnecessary risks, especially with four other carriers moving in from the south. The wisdom of this policy was soon proven. With the Japanese strike force barely out of sight the destroyer Hatsuyuki reported a large enemy force approaching from the north. Halsey’s planes had arrived.

Since 06.00 Halsey had been hurrying his carriers southwards to get within range of the Japanese Fleet, and by 09.20 his planes were lifting off from the four carriers. The air crews were all as eager to come to grips with the enemy as their Admiral, and flying over the smoking remains of Midway did nothing to lower their blood-pressure.

More than eagerness would be needed. Within minutes of sighting the Japanese armada the American pilots found themselves ploughing through the same dense flak as had greeted their comrades from Midway. The dive-bombers, arriving just ahead of the slower torpedo-bombers, bore the brunt of the nimble Zeros’ defensive fire. Only a few broke through to deliver their bombs, and all missed the scurrying Japanese carriers. But their sacrifice had not been in vain. The had drawn the Zeros up, and close to the surface the torpedo-bombers had only to contend with the ships’ anti-aircraft fire and the walls of water thrown up by the fleet’s heavy guns. As a result three Avengers cut through to launch their torpedoes at the huge bulk of the Kaga. One passed narrowly astern, the other two struck close together amidships. The carrier, holed beneath the water-line, shuddered to a halt, listing violently to port. She would take no further part in the battle, and would fmally sink that evening.

It was now 10.55, and three flights of planes were airborne: the first American strike returning to its carriers, the first Japanese strike which was nearing those carriers, and the second American strike which had just taken to the air. If this had been all, then Halsey’s confidence might have been justified. But it wasn’t. Within minutes, some 250 miles to the south, ViceAdmiral Takagi would be launching a first strike from his still undiscovered fleet. His planes would have twice as far to fly as those from the other two rapidly converging fleets. They would be making their appearance in about two hours time.

In the interlude between the launching of their first and second strikes Halsey and his subordinate Fletcher had been exchanging animated signals as to the second group’s composition. Halsey, true to his nature and the Japanese expectations, was inclined to throw everything he had at the enemy. Fletcher, showing greater reverence for the cautious aspect of Nimitz’s ambivalent instructions, wished to keep most of the fighter strength back for defence against the inevitable Japanese attack. Better to weaken the American attack, he argued, than to lose the carriers. Halsey, uncharacteristically - there is evidence that he was feeling the strain of his illness on this day - agreed to a fatal compromise. Neither enough fighters were sent with the attack to make it count, nor enough kept behind to ensure adequate protection. When Egusa’s eighty-odd planes were picked up by the radar receivers a bare eighteen fighters were waiting to engage them.

For the moment the luck went with the Americans. Yamamoto’s decision to hold back most of his fighters tended to offset the American decision. Secondly, Fletcher’s Task Force, seven miles astern of Halsey’s, was shrouded by clouds during the vital minutes and escaped the notice of the Japanese pilots. Furthermore the Japanese failed to divide their force equally against Hornet and Enterprise, and the latter escaped relatively unscathed. Two bombs hit the edge of her flight deck, two torpedoes passed narrowly by. The fires were extinguished without difficulty.

A half a mile away across the water Hornet had not escaped so lightly, having received no less than five bomb and two torpedo hits. The command post had been annihilated, killing the captain and his staff; the elevator had been blown in a twisted heap across the face of the island super-structure. Two other bombs had lanced through the flight deck and on to the hangar deck before exploding. Secondary detonations continued as the ammunition stacks caught in the raging fires. The order was given to abandon the burning, listing ship at 11.45. Over four hundred men trapped

12. The Battle of Midway

Below-decks were unable to comply and went down with the carrier twenty-five minutes later.

The score was one carrier apiece.

By this time Yamamoto and Nagumo had launched a second strike from their three functional carriers, and were preparing to receive the enemy’s second blow. News of the Hornefs demise was compensation for the loss of the Kaga. The odds, in fact, had shortened. Now it was seven against three, and planes from all seven carriers were now en route for the three Americans. It only remained to beat off the last air attack.

The sky above Yamamoto’s fleet was clear, and the American pilots had no trouble identifying the three carriers amidst the ring of warships. This advantage was offset, though, by the warning it allowed the radarless Japanese of the approaching attack. Every available Zero was soon airborne and the scenes of the previous hour were re-enacted. The ponderous torpedo-bombers, this time arriving ahead of the dive-bombers, went down in flames one by one to the combined firepower of the fighters and warships. The dive-bombers, which had strayed off-course, arrived ten minutes later, and the Zeros could not gain altitude quickly enough to prevent several screeching down against Hiryu and Soryu. The latter managed to escape any serious damage, but three 500 lb bombs hit the Hiryu"s flight deck, starting blazing fires. These were extinguished without too much difficulty, but the carrier’s ability to launch or receive planes was at an end as far as this operation was concerned. By 12.55 the fleet was once more in formation, the surviving American planes disappearing in the direction of their own carriers. They were not to find them. A hundred miles to the north-east the final act was beginning.

At 12.40 the last of the aircraft returning from the first American strike were touching down on the decks of Yorktown, Enterprise and Lexington. The flight-leaders confirmed their earlier report than an Akagi-c2iss carrier had been rendered inoperational, and probably sunk. Halsey informed them that the second strike had reported destroying another carrier. He intended to get the other two.

Fletcher did not agree, and advised a tactical withdrawal. He was not as convinced as his superior - or not so determined to assume - that these four carriers were the only Japanese carriers in the area. Where was the rest of the known Japanese carrier strength? The score at this point was two to one in the Americans’ favour; surely this was the prudent moment to withdraw.

Midway would be lost, but in the long run the three surviving carriers were more vital to the defence of Hawaii, and America itself, than one island outpost.

Unknown to either him or Halsey it was too late to avert the incoming attacks. But the fact remains that had Halsey listened to his second-incommand the catastrophe might have proved less complete. He did not listen, preferring to order a third strike on to the flight decks, thereby packing them with planes full of fuel and high explosives. It was an invitation to disaster.

At 13.09 Yorktown's radar - Enterprise's had been put out of action in the previous attack - picked up the Japanese planes closing in from the south-west. The American fighters scrambled into the air, but there was no time to launch the full-loaded bombers.

For the moment it did not seem to matter. The battle in the air went well for the Americans. Yamamoto’s caution had deprived the Japanese bombers of sufficient fighter support, radar had given the Americans ample warning, and the less experienced pilots under the veteran Fuchida found it hard to pierce the defences. Only a few hits were scored on the three carriers and none proved crippling. The surviving Japanese attackers turned for home, leaving the Americans with the brief illusion that the battle was going their way.

But at this moment a stunned radar operator on Yorktown picked up another fiight of aircraft approaching from the south-east. Fletcher’s fears had been justified. It must have been little consolation. The fleet was scattered across the sea in the aftermath of the attack; its fighter cover, in any case thinned almost to exhaustion, was dispersed and lacking altitude. The three carriers were virtually naked.

The thoughts passing through Admiral Halsey’s mind at this moment will never be known. In minutes his expectations of victory must have turned to the nightmare knowledge of certain defeat. He did not have to suffer such thoughts for long. The Pearl Harbor veterans from Shokaku and Zuikaku came diving out of the sun at the helpless carriers, lancing in across the waves through the broken screen of covering ships. Enterprise was immediately hit by at least five 500 lb bombs - three on the flight deck, one on the bridge, one on the rear of the superstructure - and two torpedoes close together amidships. There were several large explosions in quick succession and one enormous convulsion. A Japanese pilot later likened the sound to that of a motorbike revving up, and then bursting into life. Or, as in Enterprise's case, into death. Within five minutes of receiving the first bomb the ship was on her way to the bottom, the flaming flight deck hissing into

The sea. It was the fastest sinking of a carrier in naval history. There were only fourteen survivors.

Yorktown was slightly more ‘fortunate’. Also claimed by several bombs and at least one torpedo the carrier shuddered to a halt, listing at an alarming angle. Fletcher had time to order the ship abandoned, and to transfer his flag to the destroyer Russell. Yorktown went under at 14.26.

A mile away the Lexington was also in her death agonies. The target of Ryujo and Junyo's less experienced pilots, she had only received three bomb hits. But on decks strewn with inflammable material it was enough. The fires, once started, proved impossible to control, and quickly spread down through the hangar deck. The engines were unaffected, but the engine-room was cut off by the flames. Explosion followed explosion, slowly draining the giant carrier of life. At 14.55 the ‘Lady Lex’ followed her sister carriers to the bottom.

Their demise was not the end of the battle. In the daylight hours still remaining, and through the next day, the Japanese planes energetically attacked the American cruisers and destroyers as they fled eastwards for the shelter of the planes based on Oahu. Four heavy cruisers were sunk, the last of which, the Pensacola, went down at 13.30 on 29 May, some ten miles south of Disappearing Island. It was an apt postscript to the disappearance of an effective American naval presence in the Pacific Ocean.

Chapter 8 FALL SLEGFRLED

What is the use of running when we are not on the right road?

German proverb

I

Chief of the General Staff Colonel-General Franz Haider glanced out of the car window at the sunlight shimmering on the waters of the Mauersee and then turned back to the meteorological reports in his lap. In the eastern Ukraine the roads were drying; another two weeks and the panzers would be mobile along the entire Eastern Front. Fall Siegfried, scheduled to begin three weeks hence on 24 May, would not have to be postponed.

The car, en route from OKH headquarters at Lotzen to the Fiihrer’s headquarters near Rastenburg, left the sparkling Mauersee behind and dived into the dark pine forest. Haider looked at the OKW memorandum. Apparently Rommel was to assault Tobruk the following morning. With the forces at his disposal - forces, Haider reminded himself, that he could well make use of in Russia - he should have no trouble in taking the fortress. And then Egypt, Palestine, Iraq and the meeting with Kleist and Guderian somewhere in Persia? It was possible, perhaps even probable. Haider was not a man given to ‘grand plans’ - they smacked of amateurism - but he had to admit that this one had more than an air of credibility.

It would have been strange if he had thought differently, for half the ‘Grand Plan’ was in the briefcase on the seat beside him. Based on the unconsummated sections of Fall Barbarossa, drafted by the OKH operations section to Haider’s specifications, redrafted to the Fiihrer’s specifications, tested by war games at Lotzen, Fall Siegfried was designed to end the war against the Soviet Union and create the conditions for the destruction of British power in the Middle East. It was a lot of weight for a single plan to carry.

For five months the front line in the East had barely shifted. The first and most important reason for this was the unreadiness of the Wehrmacht to fight a war in Russian winter conditions. The enemy might have been virtually non-existent on some fronts, but tanks do not run in sub-zero temperatures without anti-freeze, without calks or snow-sleeves for their tracks, without salve for frozen telescopic sights. The supply system could not carry these and other essentials, plus food, clothing, ammunition and fuel a thousand miles from Germany overnight. Something had to be sacrificed, and OKH preferred to forgo a few hundred square miles of snow rather than have its forces freeze to death. As a result of this policy the Germans had suffered few casualties during the winter, either from the winter or the cold.

The second reason for the Army’s immobility during these months was a need for time to make up the losses incurred in the summer and autumn of 1941. Compared to the Red Army figures Wehrmacht casualties had been light, but they still amounted to over three-quarters of a million men and a vast amount of hard-to-replace military equipment. The panzer divisions had suffered particularly badly from the appalling road conditions, and many more tanks had been written off in this way than had been put out of commission by enemy action. Bringing these divisions back to full strength occupied the tank-factories and the training instructors for the better part of the winter.

If the condition of the Army necessitated a breathing-space, its leaders were convinced that they could get away with such a period of inactivity. The revised estimates of Soviet strength submitted to Haider by General Kinzel, head of Foreign Armies (East) Intelligence, showed that the 1941 estimates had been grossly optimistic. There had been a fifty per cent error in the manpower figure, and the extent of industrialisation in the areas beyond the Volga had not been realized. But, and here was the encouragement for Haider, Kinzel reported that the losses and disorganisation suffered as a result of the German advance had dealt a temporarily crippling blow to Soviet war industry. It was true that the enemy had managed to evacuate a large number of industrial concerns to the Volga-Ural region, but these could not possibly be fully operational before the summer. It was extremely doubtful, Kinzel concluded, that any significant rise in the Red Army’s strength would occur before the autumn. The seizure of the Caucasus oilfields, he added in an appendix, would greatly retard a possible Soviet recovery.

So, Haider had reckoned, the Army in the East could afford to sit still for five months. In that time he had tried to do something about German

Armament production, though with little success. The German war industry, contrary to popular myth but consistent with the general economic chaos of National Socialism, was, with the exception of its Italian counterpart, the most inefficient of those supplying the war. The whole business, in true Nazi fashion, was divided up between the interlocking baronies which made up the German leadership. These worthies - Todt, Goering, Funk, Thomas at OKW, Milch at OKL - competed for resources, priority, prestige, the Fiihrer’s ear, and between them achieved far less than their more single-minded counterparts in Kuybyshev and the West. Haider, who had no aptitude for threading his way through such a jungle hierarchy, could only attempt to win over the head monkey. But Hitler, as already noted, had no interest in such mundane matters as long-term production statistics. Porsche’s designs for giant tanks and miniature tanks excited him, but they were only designs. Haider wanted more Panzer Ills and IVs, not super-weapons for winning the war in 1947. He would get neither. The one time Hitler deigned to speak on the subject it was to assure his Chief of the General Staff that the war would be over by 1943, so there was no cause to worry. How this tied in with Porsche’s drawing-board fantasies was not explained. Haider was sent back to Lotzen to scheme the final defeat of the Soviet Union in 1942.

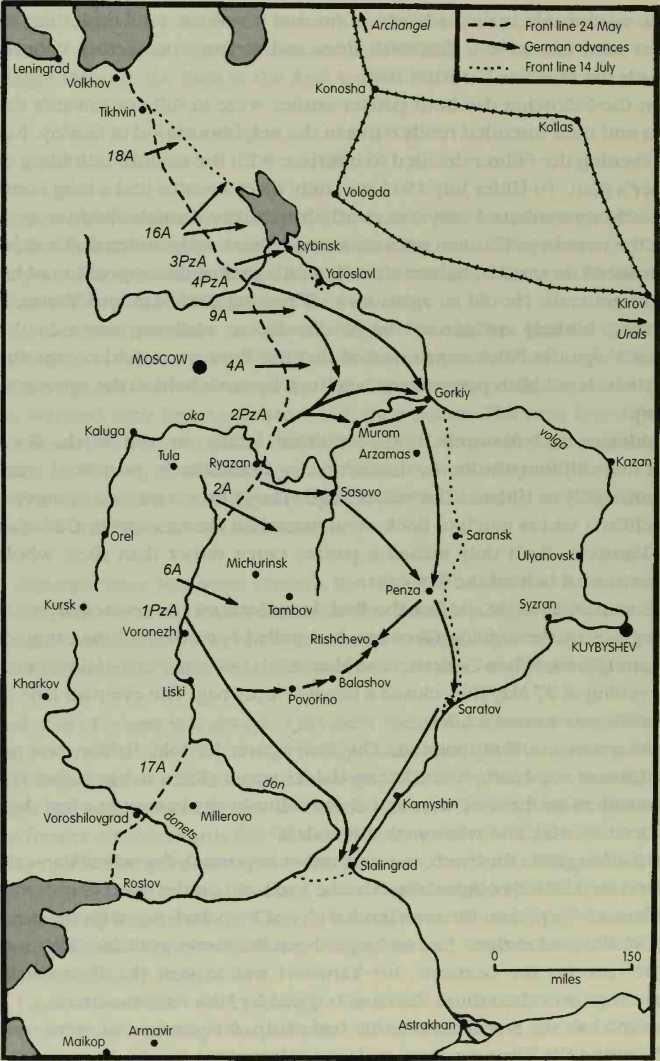

The original Barbarossa directive had laid down that ‘the final objective of the operation is to erect a barrier against Asiatic Russia on the general line Volga-ArchangeP, but had made no mention of the Caucasus. Haider, however, was committed to the conquest of the Caucasus by the Karinhall ‘Grand Plan’ decision. And he doubted if an advance to the Volga would produce results to justify the probable cost. There were no important industrial centres apart from Gorkiy west of the great Volga bend. Accordingly he ignored the Archangel-Volga line, and drafted a plan for the conquest of the Caucasus. Army Group Centre would make only a limited advance. Army Group North would take Vologda and Konosha and so cut the railways which carried Allied supplies from Murmansk and Archangel to the Volga-Ural region. Army Group South, with the bulk of the panzer forces, would move south-eastwards down the Don-Donetz land corridor, secure the land-bridge between Don and Volga west of Stalingrad, and then advance south into the Caucasus.

This plan was presented to Hitler at Berchtesgaden on 4 April. It was not well received. Unknown to Haider, Jodi had also prepared a Siegfried and Hitler had found his more amenable. Haider was treated to its salient points, though not the name of its author, and was told to redraft the OKH plan

With the following objectives: the Caucasus and the attainment of a line Lake Onega-Vologda-Gorkiy-Saratov-Astrakhan. He should bear in mind that a further advance to the Urals might prove necessary.

Hitler gave no reasons for this obsession with miles of steppe and forest. Instead he treated Haider to a lecture on the German need for the Caucasian oil. The Chief of the General Staff noted in his diary that ‘the Fiihrer’s accident does not seem to have dimmed his appetite for statistics’.

At Lotzen, through the last fortnight of April, Haider’s staff struggled to produce a Siegfried to the Fiihrer’s taste. In the end a three-stage plan was agreed. In the first stage Army Group Centre, augmented by Sixteenth Army and Fourth Panzer Army (all the panzer groups had been upgraded to army status), would attack along the front between the Oka river and Bologoye to attain a line Chudovo-Rybinsk reservoir-Volga-Gorkiy-Ryazan. Having thus secured a salient bound by the Volga and Oka rivers, Second and Fourth Panzer Armies would strike southwards with Fourth Army while Second, Sixth and First Panzer Armies struck east to meet them. Eventually a quadrilateral bounded by Ryazan, Gorkiy, Stalingrad and Rostov would be occupied, the line Hitler demanded manned by the infantry, and the armour released for Stage 3, the conquest of the Caucasus. In the far north Third Panzer Army and Army Group North would be advancing to the ordained Vologda-Onega line.

It was an audacious plan, and made more so by the same lack of reserves with which OKH had launched Barharossa. But that, the dubious Haider reassured himself, had succeeded. The testing of the plan by war game, at Lotzen on 2 May, emphasised the narrowness of the margins but still prophesied success. Hitler proved happy with the new drafting, but could not resist making a few minor alterations. The operation orders were sent out.

On 17 May, the day 20th Panzer reached the coast at Buq-Buq in North Africa, Hitler addressed his Eastern Front commanders at the Wolfsschanze. It was his usual practice to meet them half-way, but Russian distances were great and he had no intention of climbing aboard another plane. He treated the assembled company to a verbose summary of the war situation. Rommel would be in Cairo ‘in a few days’, the U-Boats were sinking more Allied merchant ships each month than they could build in six, the Japanese were proving too strong for the effete Americans. All that he asked of those present was that they deliver the final crushing blow to the disintegrating colossus in the East. That achieved, the bulk of the Wehrmacht could return to the West, there to offer a decisive deterrent to Anglo-Saxon intervention in the affairs of Europe. The war would be effectively won.

The generals listened to this glowing picture, were given no chance to ask questions, and dispersed. It was the first time most of them had seen Hitler since the accident. ‘He looks older,’ Guderian wrote to his wife, ‘and his left hand shakes terribly.’

II

In Kuybyshev Stalin did not need meteorological reports to know that the period of the spring thaw was drawing to a close: he had only to look out of the window. Soon the Germans would renew their advance, and there seemed precious little chance of stopping the initial onslaught.

But there were few signs of despair, either among the leaders gathered around the table in Kuybyshev’s Governor’s Palace or among the population at large. The devastating blows dealt by the invader had not split the Soviet Union asunder. Rather, the empty barbarism of Nazi occupation policies had served to emphasise the positive side of Stalin’s totalitarianism. Life in Soviet Russia was certainly harsh, but at least the harshness seemed to serve a purpose. The dream bom in 1917, that had soured in the succeeding years, seemed more relevant in 1942 than it had since the days of Lenin.

In the vast tracts of occupied Russia, that area of forests and marshland which stretched northwards from the borders of the Ukrainian steppe, the partisans were emerging from their winter retreats. Though still underorganised their presence would be increasingly felt in the months ahead, particularly by those unfortunates detailed to guard the long German supply-lines. In the Ukraine, where the Germans had been initially welcomed as liberators by a significant section of the population, such activity was rendered difficult by the openness of the terrain. But already the cmelties of the occupation had made active collaboration the exception rather than the mle. The loyalty of the non-Russian citizens of the Caucasus, who were yet to learn the realities of German rule, was still to be tested.

On the thousand mile frontier of unoccupied Russia the Red Army awaited the coming offensive. Despite losses exceeding eight million it was still the largest army in the world. It was also one of the worst-equipped and definitely the least-trained. Those few experienced troops who had survived the fires of 1941 were spread too thinly among the copious ranks of raw recmits; only the Siberian divisions of the Far Eastern Army were coherent, well-organised military units. And they had suffered most heavily in the bitter stmggles of early winter.

The new Red Army leadership offered some consolation for the poor state of those it had to lead. Most of those who had lost the battles of 1941, whether through incompetence or misfortune, had been replaced. Those in command in the spring of 1942 had either proved themselves extremely adept or extremely fortunate. Much had been learned, many obsolete theories cast aside. Most important of all, given the political realities of the Soviet system, Stalin himself had learnt from his mistakes. No more Soviet armies would be ordered to stand their ground while the panzers cut it from under their feet.

Still, strategic savoir faire was of limited use to an army that had a severely limited supply of tanks and aircraft. The excavation of the Gorkiy and Kharkov tank production plants had effectively halved Soviet tank production in the first five months of 1942. The removal of the Voronezh aircraft industry had a serious effect on plane production. Though both tanks and planes were being produced in the Ural region in quantities which would have shocked the Germans, for the coming campaign they were still in pitifully short supply.

So this was the material at Stavka’s disposal for averting Hitler’s next ‘crushing blow’. A large, inexperienced Army, sound leadership, insufficient armour, and an Air Force which could hardly hope to challenge the Luftwaffe for control of the Russian skies. How should it be used?

Just as Hitler and Haider had their list of objectives to gain, so Stalin and Stavka had a list of objectives to hold. Not surprisingly the lists were similar. But fortunately for the Soviet Union, and ultimately for the world, they were not the same. The priorities were different.

The Soviet decisions were taken at a routine Stavka meeting late in the evening of 4 April 1942. Those present included Stalin, Molotov, Shaposhnikov, Timoshenko, Budenny and Zhukov. The last-named argued that the greatest threat to the continued existence of the Soviet Union lay in a German advance beyond the line of the Volga. Behind that river, Zhukov continued, Soviet war industry was being rebuilt. In the cities of the great Volga bend - Kazan, Ulyanovsk, Syzran, Kuybyshev itself - and in those to the east and south, in the Urals, Siberia and Soviet Central Asia, the foundations were being laid for eventual victory. Nothing must be allowed to disturb this construction. Though there was now little hope that the Germans could be pushed back by Soviet arms alone, the growing power of the United States and the continued defiance of Britain would eventually diminish the German presence on Soviet soil. Then these new foundations would prove their worth. As the German power decreased the Soviet power would rise. Then would be the time to march west.

As Zhukov outlined his case Stalin, as was his habit, walked up and down behind the lines of seated generals and marshals, puffing pipe smoke out into the room and occasionally stopping to gaze out of the window at the moonlit Volga. Every now and then a sharp report was audible inside the room, as another stretch of ice cracked in the thawing river.

Shaposhnikov raised the question of the Caucasus. ‘Can these industries east of the Volga maintain their production without the Caucasian oil?’

‘Of course the retention of the Caucasus is vital,’ Zhukov replied. ‘But we do not have the forces to defend all those areas that are vital.’ He took a memorandum from his attache case. ‘And it seems that the Caucasus is not so vital as the Germans believe, or as we ourselves believed. The oilfields in the Volga-Kama, Ukhta, Guryev and Ural regions are now being developed at the fastest possible speed. According to this report we can survive, at a pinch, without the Caucasian oil. And this is a pinch. The defence of the Caucasus must come second to the defence of the Volga line.’

Stalin, the Georgian, said nothing. Which usually implied agreement. Shaposhnikov was not satisfied. What about the aid from the West? Was it not vital to keep open the southern ingress route, which passed through the Caucasus?

Zhukov reached for another memorandum. ‘Work on the new road between Ashkabad and Meshed in northern Persia is well advanced. Of course this road will not have the capacity of the trans-Caucasus route, but it will be better than nothing. The southern ingress route is not the only one. The Archangel railway is carrying a substantially greater volume of goods. And even if Vologda falls - which is likely - the terrain between there and Konosha is most unsuitable for the enemy’s armoured formations. We have a much better chance of holding this route open. And even if it were closed, there is still Vladivostok. Unless the Japanese win a great victory over the Americans they will not add to their list of enemies by attacking us in the Far East. If they do, if the worst comes to the worst, we shall have to carry on without outside aid. We will have no choice. But we must hold the Volga line, or there will be nothing left to carry on for!’

The meeting went on into the early hours, but Zhukov’s list of priorities was not questioned in principle. The Red Army’s dispositions in the following weeks reflected these priorities. The front was now divided into nine Fronts - North, Volkhov, North-west, West, Voronezh, South-west, South, North Caucasus and Caucasus - comprising twenty-six armies or roughly three and a half million men. Half of these armies were attached to only two Fronts, West and Voronezh, holding the centre of the line between the Volga below Kalyazin and Liski on the Don. Of the six armies held in

Reserve, four were deployed behind these two Fronts. If the Germans intended a straight march east towards the Urals they would have to go straight through the bulk of the Red Army.

M

An hour before dawn on 24 May the German artillery began its preliminary bombardment, and as the sun edged above the rim of the eastern horizon the panzer commanders leaned out of their turrets and waved the lines of tanks and armoured infantry carriers forward.

In the German ranks morale was high. The soldiers had survived the rigours of a winter that would once have been beyond their darkest imaginings, and now it was spring. The leaves were on the trees, the pale sun warmed their feet, their hands and their hearts. The next few months would see this business in the East finished. And then at best there would be peace and home, at worst a more amenable theatre of operations.

The commanders were equally optimistic. Guderian, up with the leading tanks of 2nd Panzer, was later to write:

Although there was some concern that the final objectives of the summer campaign were not clearly defined, and that this lack of clarity might encourage interference from the Supreme Command (i. e. Hitler), there was little doubt in any of our minds that the war in the East would be concluded before the autumn.

Guderian of course was always at his most optimistic when moving forward, and Second Panzer Army was certainly doing that. On the opening day of the campaign the two strong panzer corps, 24th and 47th, burst through the weak link between the Soviet Twenty-fourth and Fiftieth Armies, throwing the former south towards the Oka and the latter north into the path of von Kluge’s advancing infantry. By evening on that day the leading elements of 2nd Panzer had broken through to a depth of thirty miles and were approaching Lashma on the Oka. Fifteen miles to the north 3rd Panzer was nearing Tuma. The Soviet forces facing Second Panzer Army had been comprehensively defeated.

One-hundred-and-twenty miles to the north, on the other wing of Army Group Centre’s attack. Fourth Panzer Army was having greater difficulty breaking through the Soviet Fifth Army’s positions on the River Nerl. This unexpectedly stubborn resistance forced Manstein, who had relieved the sick Hoppner as Panzer Army commander, to shift the scbwerpunkt of his

Attack southwards in the early afternoon, and it was not until dusk that 8th Panzer was free of the defensive lines and striking out across country towards the Moscow-Yaroslavl road.

On the following day both panzer armies were in full cry towards the Volga and their intended rendezvous in the neighbourhood of Gorkiy. But that evening the Eiihrer decided to interfere with the smooth unfolding of Haider’s plan. To Hitler July 1941 was only three months and a long coma away. He remembered only too clearly how many Russians had escaped from the over-large German pockets around Minsk and Smolensk. Then he had insisted on smaller, tighter encirclements against the opposition of his panzer generals. He did so again now. Watching Guderian and Manstein motoring blithely on across the Wolfsschanze wall-map towards the distant Volga the Eiihrer again feared that the Russians would escape the net. He ordered both panzer armies to turn inwards behind the retreating enemy.

Guderian and Manstein both protested loudly to von Bock. Bock protested diplomatically to Brauchitsch. Brauchitsch protested very diplomatically to Hitler. A day was wasted. The Fiihrer remained unmoved. Brauchitsch said as much to Bock, who passed on the message to Guderian and Manstein. Both duly turned a panzer corps rather than their whole armies inward behind the Russians.

Or so they thought. In fact the Red Army formations, granted an extra day’s grace by the arguing Germans, had pulled back beyond the range of the gaping jaws. When Guderian and Manstein’s units met east of Kovrov on the evening of 27 May they closed a largely empty bag. The eventual tally of prisoners was a mere 12,000.

Hitler was not disappointed. The low figure, he told Haider, was an indication of the enemy’s weakness. Haider was inclined to agree, but the commanders on the spot were not so sure. But in any case only a few days had been wasted, and what were a few days?

In the long term they were to prove rather important. For when Manstein had received Hitler’s original directive he had been on the point of ordering 4lst Panzer Corps into the undefended city of Yaroslavl. But with the need to close the pocket there had no longer been the forces available. This was unfortunate for the Germans, for Yaroslavl was to cost the Wehrmacht many more lives than those Russians trapped by Hitler’s manoeuvre.

Meanwhile the Soviet armies that had escaped encirclement were now back behind the Klyaz’ma river, and Guderian’s panzers were held up for a further two days by resolute defence. Then, to the Germans’ surprise, the Russians withdrew during the night of 30 May. Apparently they were not

13. Fall Siegfried

Going to stand their ground and fight to the last as in the previous year. This new devotion to elastic defence was disturbing.

Fortunately for the Germans the same day offered evidence that the Red Army had not yet shaken off all its bad habits. With that incompetence which the Master Race found more typical of their enemy the Soviet forces in Murom allowed 2nd Panzer to seize the road and rail bridges across the Oka intact. By morning on 31 May a sizeable bridgehead had been established, and the whole of 47th Panzer Corps was being funnelled through on to the right bank of the river. Two days later, as Manstein’s tanks reached the Volga north of Gorkiy, Guderian’s were cutting the city’s road and rail links to the south and east.

Here again Hitler attempted to interfere, though with less success. He forbade Guderian to enter the city; panzer forces were not suitable for urban warfare, and Gorkiy would have to wait for the infantry, still some eighty miles to the west. Guderian, while agreeing in principle, thought it senseless to allow the enemy three or four days to prepare defences in what was virtually a defenceless city. He informed Bock that the order could not be obeyed, as 29th Motorised was already engaged within the city limits. Having done so he ordered 29th Motorised to engage itself within the city limits. Hitler bowed to the apparently inevitable. On 3 June the last Red Army units in the city withdrew across the Volga, and the swastika was hoisted above Gorkiy’s Red Square.

It was not yet fluttering above Yaroslavl. By-passed by the panzers when occupation would have been little more than a formality, the city was being feverishly prepared for defence as Ninth Army ponderously approached the flaming chimney beacons from the west. On 3 June the first battles were beginning in the vast textile factories of the ancient city’s western suburbs. No one in the German or Soviet High Commands foresaw that Yaroslavl’s reduction would take six weeks and cost the Germans 45,000 casualties. The beginnings of this battle were ignored for, with the capture of Gorkiy, all eyes were now fixed on the Oka line, springboard for Stage 2 of Siegfried, the great march to the south.

IV

In Kuybyshev Stavka waited. Where would the enemy strike next? Zhukov, who had been Stavka’s representative at West Front HQ during the preceding fortnight, had been relieved to see that the Germans were making no attempts to secure bridgeheads across the Volga between Gorkiy and

Yaroslavl. A panzer advance downstream along both banks would have presented formidable problems. But, given that the enemy had eschewed such a tempting opportunity and, further, given that his armour was still concentrated north of the Oka, it seemed most likely that a direct march east across the Volga Uplands was intended. And this was barely less dangerous. Stavka knew that there was no natural line short of the river that the Red Army could hope to hold. All the strength it possessed would be needed to hold the river-line itself. It was re-emphasised to all Front, army and divisional commanders that on no account should they allow their formations to be encircled by the German armoured units; they were to fight, retreat, fight and retreat again, if necessary - and it probably would be - all the way back to the Volga.

In Hitler’s Rastenburg HQ, now over 800 miles from the front, little attention was paid to the possible responses of the enemy. As always the German strategic intelligence was as poor as the tactical intelligence was good. The paucity of prisoners taken in Stage 1 was attributed to the Red Army’s lack of manpower; reports from the Front that the Soviet formations were showing a new awareness of the tactical values of withdrawal were given little credence. It was estimated that there were approximately 120 Soviet divisions on the line Gorkiy-Sea of Azov, and the Fiihrer expected most of them to fall into the bag during Stage 2. In these early June days the atmosphere at Rastenburg was little short of euphoric. Cairo had fallen, Gorkiy had fallen. The Japanese had won a major victory in the Pacific. Everything was going right. There was no reason why Stage 2 should go wrong.

On the morning of 17 June Army Group Centre rolled forward into the enemy once more. This time Second Panzer Army was on the left wing. Fourth Panzer Army having been moved to the Ryazan area during the second week of the month. The two armies made rapid progress. Such rapid progress in fact that even Haider began to grow suspicious. Prisoners were scarce, the Russians coolly fighting their way backwards. Guderian’s tanks rumbled into Arzamas, Manstein’s reached the Tsna river south of Sasovo. Second Army took Ryazsk on Manstein’s right flank. Fourth Army moved forward between the two panzer armies.

For the next few days the panzers rolled on through pasture lands broken by large stretches of deciduous forest. The stukas swooped down on the retreating Red Army, the tanks sent up their clouds of dust, German commanders examined their inadequate maps by the light of burning villages. All the familiar horror of blitzkrieg spread southwards towards the open steppe.

The miles slipped away beneath the panzers’ tracks at a rate not seen since the previous summer. On 23 June Guderian’s advance units had travelled two hundred miles and were approaching Penza from the north. The next day they met Manstein’s vanguard south-east of the town. Another huge pocket had been created. But again the haul of prisoners and equipment was disappointing. And many of those forces which had been caught in the encirclement found little difficulty in breaking through Guderian’s thin screen and escaping to the east.

Four hundred miles to the north the struggle for possession of Yaroslavl was entering its third week. Hoth’s panzers had secured a bridgehead over the Volga to the east of Rybinsk, and the Army Group North commander Field-Marshal von Leeb had planned to use them to cut off Yaroslavl’s communications to the north. But as he was about to set this process in motion Hitler, worried about the long front south of the Don which was held by only Seventeenth Army and the armies of Germany’s allies, demanded that Hoth’s Panzer Army should part with one of its two panzer corps. Ninth Army would have to continue its struggle for the factories, sewers and cellars of Yaroslavl with insufficient support.

On 23 June the two northernmost armies of Army Group South - Sixth Army and First Panzer Army - joined the drive to the south-east. Kleist’s panzers struck east and south-east, towards Balashov and along the left bank of the Don. Simultaneously Manstein and Guderian were preparing to resume their southward march.

Another week passed. On 30 June the pincers closed again, this time outside the railway junction of Rtishchevo. Further east Guderian’s panzers, aimed on Saratov, were checked for the first time in the neighbourhood of Petrovsk. The leading units of 2nd Panzer were assailed by a Soviet armoured brigade and suffered unexpected casualties. The continuation of the German advance had to wait for 18th Panzer’s arrival the following afternoon. The Soviet tanks melted away to the east.

Guderian continued south, reaching the Volga above Saratov on the morning of 2 July, and cutting the railway entering the city from the west twenty-four hours later. Saratov seemed well-defended, so this time the refractory general obeyed the orders from Rastenburg to place a screen round the city rather than attempt its capture. 47th Panzer Corps moved on down the right bank of the great river. Its tanks had now covered over five hundred miles since 24 May and the strain was beginning to tell. Though losses in action had been negligible, the attritional qualities of the Soviet roads had exerted a formidable toll on the vehicles.

In the Wolfsschanze such things were not visible on the wall-maps. All these showed was the relentless march of the German forces. Siegfried was succeeding. All was well.

In Kuybyshev, strange though it would have seemed to Hitler and his henchmen, spirits were also rising. The southern thrust of the German armour had brought that same relief with which the French High Command had greeted von Kluck’s fatal turn to the south outside Paris in August 1914. Then General Gallieni, the Military Governor of the French capital, had transported troops in taxis to attack the exposed German flank. Stavka had no such options available to it, but the Soviet leaders could bear such inconvenience. What mattered, what really mattered, was that the panzers were streaming southwards, away from the crucial line, away from a swift end to the war in the East.

Their own armies were withdrawing steadily towards the Volga. Though often outflanked by the German armour and pummelled by the screaming Stukas the Red Army refused to break up and die as it had the previous year. Skilful leadership in the field and intelligent use of propaganda played their part in encouraging this fortitude, but the most telling factor was Stavka’s simple common-sense tactical directive: fight until threatened with encirclement, and then withdraw. Of course a large proportion of the Soviet forces were encircled at one time or another, but the enormity of space on the steppe and the profusion of forests in the northern half of the battle-zone offered ample opportunities for escape. The German lines were too thin on the ground, the Luftwaffe too thin in the sky, to dominate such a vast area. The major portion of the West and Voronezh Front armies had reached the line Gorkiy-Saransk-Saratov-Stalingrad by the end of the first week of July.

Their retreat left South-west and South Fronts, covering the Don-Sea of Azov line, in an exposed position, and as Kleist’s tanks neared the Don-Volga land-bridge west of Stalingrad on 6 July Zhukov ordered the two Front commanders to withdraw their armies south-eastwards to the line of the Don. Hoth’s panzer corps, which had just arrived in the ‘threatened sector’ was ordered back to the north by Hitler, to the exasperation of all others concerned. Seventeenth Army, and the Italian, Rumanian and Hungarian formations, moved forward into the vacuum left by the retreating Russians.

Stage 2 of Siegfried was almost complete. On 8 July Guderian’s tanks entered the northern outskirts of Stalingrad as Kleist’s moved in from the south-west. After two days’ skirmishing the Red Army fell back across the mile-wide Volga. Upriver Sixth Army was fighting its way into Saratov. The central section of the line Archangel-Astrakhan had been reached. As Ninth

And Third Panzer Armies prepared for the final onslaught on Yaroslavl, Eleventh, Seventeenth, First Panzer and Second Panzer Armies deployed for the invasion of the Caucasus.

World History

World History