Throughout March 1945, the Red Army had fought in both East Prussia and Hungary against German forces which, however battered and weakened, were determined not to yield, but only to be annihilated. On the Baltic coast, on March 27, Gdynia, Danzig, and Konigsberg were all under siege. In Hungary, tens of thousands of German soldiers were surrounded at Esztergom on the eastern bank of the Danube north of Budapest; on March 28, on the western bank, the Red Army entered Gyor, only seventy-five miles south-east of Vienna.

Hitler’s more fanatical followers still spoke in terms of victory. On March 28, as American troops entered Marburg and Lauterbach—only two hundred miles from Berlin —the thirty-one year old Hitler Youth Leader, Arthur Axmann, told the Hitler Youth now under arms: ‘It is your duty to watch when others are tired; to stand fast when others weaken. Your greatest honour, however, is your unshakeable faithfulness to Adolf Hitler.’

‘Faithfulness’ was a much abused word in the spring of 1945. On March 28, at Pruszkow, near Warsaw, the second of two groups of Polish political leaders, nonCommunists, went under safe conduct for consultations with senior Soviet officers. They were immediately arrested, and taken as prisoners to Moscow. Also sent to prison was Raoul Wallenberg, who had earlier done so much in Budapest to help save Jews from deportation to Germany. He too went to parley with the Russians when they reached the city, and he too was arrested. According to one Soviet account, he died a few years later in prison in Moscow.

On March 29, Soviet troops captured the Hungarian city of Kapuvar, and advanced into Austria, only fifty miles from Vienna. In Germany, American troops captured Frankfurt. That same day, at Flossenburg concentration camp, several dozen Allied agents—Englishmen and Frenchmen among them—were executed. Many sang the Marseillaise on their way to the scaffold, and cried out ‘Vive la France!’ or ‘Vive l’Angleterre!’ as their last words. Among the British agents killed that day was Captain Isadore Newman who, in the weeks after the Normandy landings, had, from behind German lines, transmitted and received hundreds of messages to and from Supreme Allied Headquarters and French Resistance fighters in northern France. After his capture, despite abominable tortures, Newman had refused to betray any of his vital secrets.

Another British agent, the Canadian Gustave Bieler, who had been severely injured when he had parachuted into France, was also executed that day. He was said by one German eye-witness to have made such a powerful impression on his captors that when the time came for his execution, they mounted a guard of honour to escort him, as he limped to his death.

At Buchenwald that same March 29, the Germans ordered Captain Maurice Pertschuk to go to the camp guard-room. Pertschuk had been held prisoner in Buchenwald for three years, having also been captured in France while on special operations for British Intelligence. When a friend tried to stop him answering the order to go to the guard room, he replied: ‘You know what happens when someone refuses to go, they take a hundred hostages and murder them’. Captain Pertschuk went, as ordered. He too was hanged.

At Buchenwald, out of a prisoner population of 82,000, a total of 5,479 had died that March of illness, starvation and ill-treatment, bringing the total deaths there to 17,570 in three months.

At Ravensbruck, on March 30, a number of Jewish women who were being led to their execution struggled with the SS guards. Nine managed to escape, but were soon recaptured, and then executed.

Over Germany, Allied bombers continued to fly virtually unchallenged. On March 30, in an American daylight raid on the German submarine base at Wilhemshaven, the u-96 was sunk, the latest of hundreds of u-boats to be destroyed. Among those killed was its Captain, Heinrich Lehmann-Willenbrock, who in his time had sunk twenty-flve Allied merchant ships, with a total tonnage of 183,253. Another ace, the flghter pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel, was shot down that month, and badly injured, losing his right leg. The most highly decorated soldier in the Third Reich, Rudel was the only holder of the Knight’s Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. The Golden Oak Leaves, awarded in January 1945, were unique to him. Rudel had been credited with having destroyed 532 Russian tanks from the air, during the course of 2,530 operations. In March 1944 he had been shot down by the Russians and captured, but had escaped.

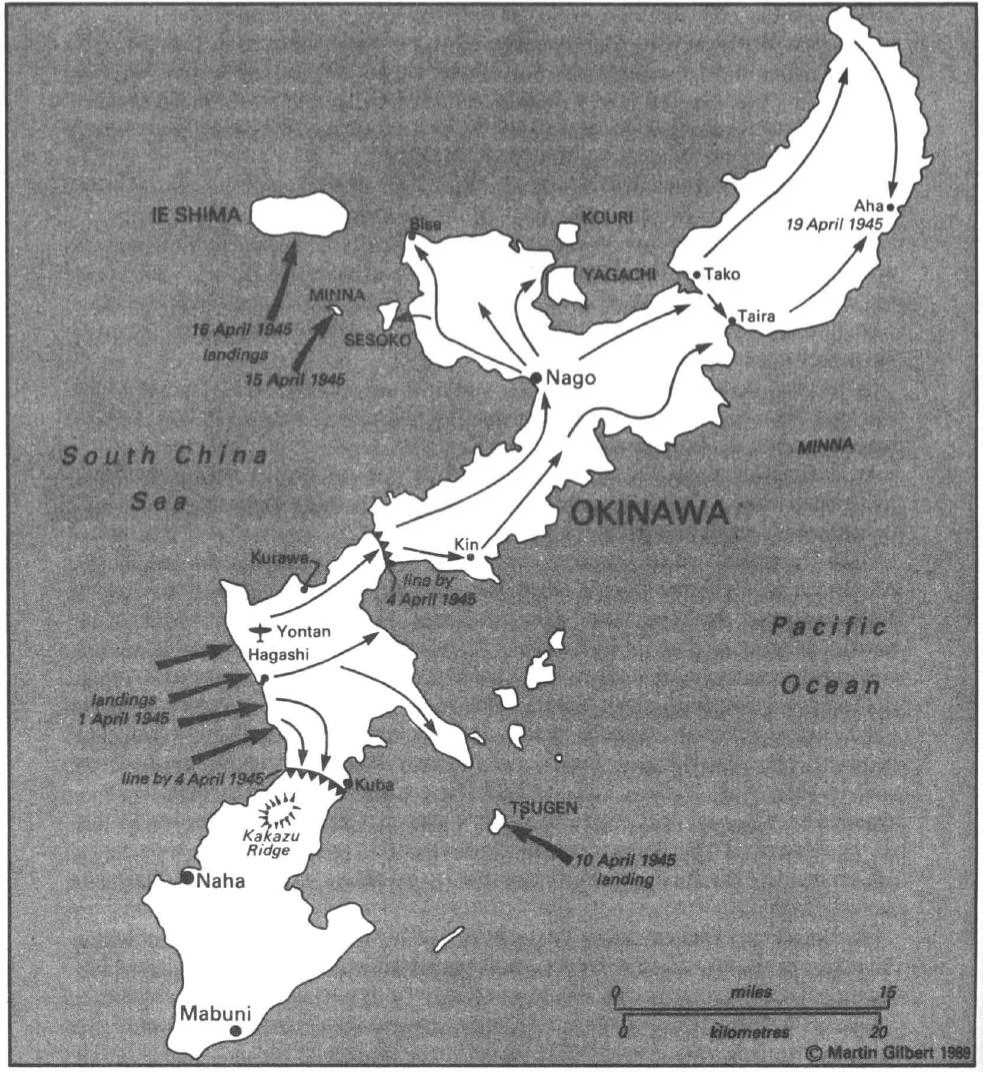

On March 31, French forces crossed the Rhine at Speyer and Germersheim. That day, in the Paciflc, the Americans completed their flve day conquest of the Kerama island group, in the Ryukyu chain; 530 Japanese had been killed on Kerama Retto, for the cost of thirty-one American dead. During the battle, 350 Japanese ‘suicide boats’ had been found, and captured intact. Then, on the following day, April 1, also in the Ryukyus, the Americans launched the greatest land battle of the Paciflc war, Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa.

Fifty thousand American troops landed on Okinawa on the morning of April 1, Easter Sunday, on an eight-mile-long beachhead. Twice that number of Japanese were entrenched on the island. The landing, however, was unopposed, leading the American troops to change their slogan from ‘The Golden Gate in ’48’ to ‘Home Alive in ’45’. But then the Japanese attacked the bridgehead, with all the ferocity of men defending their homeland. In twelve days of ruthless flghting, the Americans gained less than two miles. But the capture of Okinawa was an essential prelude to the invasion of Japan, which was a mere 360 miles away, to the north-east.

The landings on Okinawa, 1 to 23 April 1945

The battle of Okinawa was to last for eighty-two days, with 180,000 American combat troops involved, and a further 368,000 American troops in support. The fighting was ferocious—hand to hand and bayonet against bayonet. Once more the Japanese soldiers fought until killed; but, in the last days of the battle, more than seven thousand were willing to be taken prisoner. Almost every American soldier who was captured by the Japanese was killed after being captured. At sea off Okinawa, thirty-four American warships were sunk, many as a result of attacks by individual Japanese suicide pilots. A

Total of 1,900 kamikaze attacks were launched, and a further 5,900 Japanese aircraft shot down in combat, for the loss of 763 American warplanes.

At least 107,500 Japanese soldiers were known to have been killed on Okinawa, an average of just over thirteen hundred a day. A further 20,000 Japanese are thought to have perished in caves sealed by American assault teams, using flame throwers and explosives. It has also been calculated that 150,000 local Okinawan civilians were killed. American losses were 7,613 killed on land and 4,900 at sea.

In all, more than a quarter of a million human beings died in and around Okinawa in the spring and early summer of 1945.

On April 1, in Berlin, Hitler moved his headquarters from the Chancellery building to a bunker system behind the Chancellery, and deep below it. That same day, in Moscow, Stalin asked his commanders: ‘Well, now, who is going to take Berlin, will we or the Allies?’ and he set April 16 as the day on which the Soviet campaign against the German capital should begin. Also on April 1, in Hamburg, Himmler told the City Council that disagreements among the Allies, as well as the imminent use of German jet aircraft in large numbers, would give Germany decisive breathing space.

No such breathing space, however, was to be allowed; the Western Allies, albeit with reluctance, agreed to make central Germany and Czechoslovakia their main target, allowing the Red Army to reach Berlin flrst. As for the German jet aircraft, they were to be shot out of the skies.

As the Red Army prepared for its attack on Berlin, Soviet forces on the Danube front reached the Austrian border at Hegyeshalom, less than seventy miles from Vienna. That same day, April 2, Soviet and Bulgarian troops captured Nagykanizsa, the centre of the Hungarian oilflelds. Germany’s last hope of an adequate fuel supply to make war was lost. A counter-attack that day in the Ruhr, led by General Student, had to be postponed because of a lack of tank fuel; this fact was known to the Allies through Ultra.

Not only fuel oil, but essential medical supplies, were now virtually unobtainable within the dwindling conflnes of the Reich; on April 2 the head of Germany’s medical services, Dr Karl Brandt, warned Hitler personally that one-flfth of all medicines needed no longer existed, and that stocks of two-flfths would run out completely in two months. But Hitler refused to accept even the possibility of surrender, and in a message to Field Marshal Kesselring, sent on April 2, he ordered the replacement of every commander in Italy who failed to stand firm.

In London, Churchill looked uneasily at the Soviet advance, and in particular at what was happening in Poland, where it had become clear that the free elections, promised by Stalin at Yalta less than three months earlier, would not take place. As early as March 23, having read the reports from Averell Harriman in Moscow, Roosevelt had told a close friend: ‘Averell is right. We can’t do business with Stalin. He has broken every one of the promises he made at Yalta.’ On April 2, Churchill telegraphed direct to General Eisenhower, suggesting that it might even be possible for the Western Allies to

Advance eastward to Berlin. ‘I deem it highly important’, he wrote, ‘that we should shake hands with the Russians as far to the East as possible.’

On April 3 the Anglo-American forces completed their encirclement of the Ruhr. Prisoners were being taken at the rate of between 15,000 and 20,000 a day. The conquest of Germany could now be only a matter of two months at the most. That day, Churchill gave May 31 as the date ‘towards which we should now work’, but he added: ‘it may well be that the end will come before this’, possibly ‘on 30th April’. But the political and ideological clash over Poland cast a dark cloud over the imminence of victory. ‘The changes in the Russian attitude and atmosphere since Yalta are grave,’ Churchill wrote to the Chiefs of Staff Committee on April 3. To the Dominion and Indian representatives who attended the War Cabinet in London that day, Churchill warned: ‘Relations with Russia, which had offered such fair promise at the Crimea Conference, had grown less cordial during the ensuing weeks. There had been grave difficulties over the Polish question; and it now seemed possible that Russia would not be willing to give full co-operation at the San Francisco Conference on the proposed new World Organization. It was by no means clear that we could count on Russia as a beneficent infiuence in Europe, or as a willing partner in maintaining the peace of the world. Yet, at the end of the war, Russia would be left in a position of preponderant power and influence throughout the whole of Europe’.

Fears of Soviet predominance in Europe did not stop the signature, on April 3, of a final package of British and American aid to Russia, code-named ‘Milepost’. Under this agreement, Russia was to receive, and did receive, more than a thousand fighter aircraft and 240,000 tons of aircraft fuel, as well as 24,000 tons of rubber from Britain, and more than three thousand aircraft, three thousand tanks, nine thousand jeeps, sixteen thousand weapon carriers and 41,436 trucks from the United States, as well as nearly two thousand million dollars worth of machinery and equipment.

On April 3, an American armoured division was approaching the German town of Gotha. Among the war correspondents attached to the division was a Jewish novelist, Meyer Levin, who later recalled how he and his companions came upon some ‘cadaverous refugees’ along the road. ‘They were like none we have ever seen,’ Levin wrote: ‘Skeletal with feverish sunken eyes, shaven skulls.’ They identified themselves as Poles and asked Levin and the others to come to the site where they had been held prisoner. They spoke of ‘People buried in a Big Hole’ and ‘Death Commando’.

On the following morning, American troops entered the site of which the refugees had spoken. The name of the place was Ohrdruf, and just inside the camp entrance were hundreds of corpses, all in striped uniforms, each with a bullet hole at the back of the skull. In a hut were more corpses, naked, stacked up, as Levin recalled, ‘fiat and yellow as lumber’.

It soon became clear the Ohrdruf was neither a labour camp nor a prisoner-of-war camp, but something else: a camp in which four thousand inmates had died or been murdered in the previous three months. Hundreds had been shot on the eve of the American arrival. Some of the victims were Jews, others were Polish and Russian

Prisoners-of-war. All had been forced to build a vast underground radio and telephone centre, intended for the German Army in the event of a retreat from Berlin.

Among those who had been held at Ohrdruf was a young Polish Jew, Leo Laufer. Four days before liberation, he had managed to escape, as the evacuation of the camp began, running off with three fellow prisoners. For four days they had hidden in the hills above Ohrdruf. When the American forces and war correspondents arrived, Laufer accompanied them into the camp. Many of the corpses which they found there were of prisoners who had been in the camp sick bay four days earlier.

The sight of the emaciated corpses at Ohrdruf created a wave of revulsion which spread back to Britain and the United States. Eisenhower, who visited the camp, was so shocked that he telephoned Churchill to describe what he had seen, and then sent photographs of the dead prisoners to him. Churchill, shocked in his turn, circulated the photographs to each member of the British Cabinet.

On April 4, as American troops entered Ohrdruf, opening up a horrific vista of what had gone on in wartime Germany, General Student was forced, through lack of fuel, to cancel altogether the counter-attack, postponed two days earlier, against the Allied forces in the Ruhr. There was now no section of the front line through which the Western Allies could not break. At the same time, by a careful scrutiny of the Germans’ own Ultra messages, it was possible for the Allies to anticipate each change of German plan and each intended counter-attack; top-secret details of one particularly strong German counter-attack, from Muhlhausen towards Eisenach, intended to begin on April 6, were decrypted in time for the counter-attack to be met and defeated.

The Red Army was now fighting in the suburbs of Vienna, and making its final plans for the assault on Berlin. In the air, the last of Germany’s once dominant Air Force struggled in vain against the daily mass of Allied bombers and fighters. On April 4, over the Eastern Front, Hermann Graf was shot down; he had to his credit a total of 202 Soviet aircraft destroyed on the Eastern Front, for which he had been awarded the coveted Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. Now he too, taken eastward into captivity, was a witness to the destruction of German military and air power.

Churchill had seen April 30 as a possible date for the end of the war in Europe. The war in the Pacific was going to be a far longer struggle. On April 5, the Americans began planning for Operation Olympic, the invasion of the southernmost Japanese island of Kyushu, set for 1 November 1945, to be followed by Operation Coronet, the invasion of the principal Japanese island of Honshu, to take place on 1 March 1946, using troops to be brought from Europe after the defeat of Germany. Both operations were expected to be exceptionally violent and bloody, an expectation which was heightened on April 6, when, off Okinawa, the Japanese Air Force launched its own Operation Floating Chrysanthemum, the use, instead of single suicide pilots, of 355 such pilots in a single stroke. So successful was this initial attack that two American destroyers, two ammunition ships and a tank landing ship were sunk; but at the loss of 355 Japanese aircraft and pilots.

On April 7, there was yet another suicide attack at Okinawa. It was made by the largest battleship in the world, the 72,800-ton Yamato, which, with only enough fuel to reach Okinawa, carried out a suicide mission against the American transport fieet. Its

Eighteen-inch guns never achieved their object however; struck by nineteen American aerial torpedoes, the Yamato was sunk, and 2,498 of her crew drowned. In the same suicide attack, the cruiser Yahagi and four destroyers were likewise sunk, with a further loss of 446 men on the cruiser and 721 on the destroyer. Of 376 American aircraft taking part in the operation, only ten were lost.

Even over Germany, a virtual suicide operation now took place, with 133 aircraft being lost, and seventy-seven pilots killed, in a mass German attack on American bombers, in which only twenty-three of the bombers were shot down. That same day, April 7, in Yugoslavia, German forces evacuated Sarajevo and began their withdrawal from the Dalmatian coast. In Czechoslovakia, Bratislava fell to the Red Army. In Austria, the battle for Vienna continued. In Silesia, the Germans holding out in Breslau were being systematically destroyed.

To the bitter end, Hitler was determined that his enemies would not survive. On April 8, Hans von Dohnanyi was murdered in Sachsenhausen, and on the following day Admiral Canaris, General Oster and Dietrich Bonhoeffer were hanged at Flossenburg, less than 150 miles from the American spearhead moving eastward from Gotha. Also on April 9, at Plotzensee Prison in Berlin, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin was beheaded. As early as 1932 he had denounced Nazism as ‘lunacy’ and ‘the deadly enemy of our way of life’. In 1944 he had invited several German resistance groups to meet at his country estate, at Schmenzin.

In Dachau, among tens of thousands of prisoners awaiting liberation, was Johann Elser, the carpenter who had tried to assassinate Hitler in November 1939; he too was now to die, murdered on April 9 on Himmler’s orders.

In Italy, April 9 saw a renewed Allied attack on the German ‘Gothic Line’ defences, with British, American, Polish, Indian, New Zealand, South African, Brazilian and Jewish Brigade Group troops taking part. That evening, on the Baltic, the fortress commander of Konigsberg, General Otto Lasch, ordered his troops to surrender; 42,000 of his men had been killed and 92,000 captured during the battle to hold the city. Also killed were 25,000 German civilians, a quarter of the city’s inhabitants, whom the Nazi authorities in Konigsberg had refused to allow to be evacuated. On the following night, Hitler telegraphed to the few German radio units still operational in East Prussia: ‘General Lasch is to be shot as a traitor immediately.’ But Lasch was already a prisoner-of-war.

In western Germany, on April 9, the Allied forces were confronted by a German Army, commanded by General Wenck, which had taken up a strong defensive position in the Harz mountains. Hitler, in Berlin, had great hopes of Wenck, both in holding up the Allied advance and in being able, if necessary, to hurry back the hundred miles to Berlin, should the Russians get much closer to the city. Within nine days, however, Wenck’s forces were surrounded, as the Allied armies, leaving him encircled, drove on eastward to Halle and to the River Elbe.

North of Berlin, on April 10, American pilots began what came to be known as the ‘Great Jet Massacre’, shooting down fourteen German jets over Oranienburg. That same day, the British public learned from their Prime Minister of the scale of British war

Deaths between September 1939 and February 1945: 216,287 fighting men on land, sea and air; 59,793 civilian casualties in Britain from air raids, fiying bombs and rockets; and 30,179 merchant seamen—a total of more than 300,000 deaths.

On April 11, the Soviet Union signed a treaty of friendship, mutual aid, and post-war collaboration with Tito’s Yugoslavia. The Red Army was now master of Hungary, and of eastern Czechoslovakia. In Vienna, Soviet troops had reached the city centre. The Western Allies, too, were not without resources; on 11 April American forces reached the Elbe just south of Wittenberge, less than eighty-five miles from the centre of Berlin. Yet Eisenhower now agreed, in consultation with the Soviet High Command, that American forces would not move on to the German capital, but would push south and east.

On April 11, the Gestapo headquarters at Weimar telephoned the camp administration at Buchenwald camp, to announce that they were sending up explosives to blow up the camp and its inmates. But the camp administrators had already fied, and the inmates were in charge of the camp; answering the telephone, they told the Weimar Gestapo: ‘Never mind, it isn’t necessary. The camp has been blown up already’.

Thus the inmates of Buchenwald were saved; at the eleventh hour, luck had protected those whom evil had sought to destroy. A few hours later, American troops entered Buchenwald, where a scene of terrible deprivation confronted them: a sickening picture of emaciated corpses and starving survivors. One of those whom they liberated there, Elie Wiesel, later wrote: ‘You were our liberators, but we, the diseased, emaciated, barely human survivors were your teachers. We taught you to understand the Kingdom of Night.’

World History

World History