The reconquest of New Guinea, which was completed in mid-January, cost MacArthur dear and, in view of his losses and the enemy’s tenacity, he decided to soften down his methods, as he wrote in his memoirs:

"It was the practical application of this system of warfare-to avoid the frontal attack with its terrible loss of life; to by-pass Japanese strongpoints and neutralise them by cutting their lines of supply; to thus isolate their armies and starve them on the battlefield; to as Willie Keeler used to say, 'hit 'em where they ain’t’-that from this time guided my movements and operations.

"This decision enabled me to accomplish the concept of the direct-target approach from Papua to Manila. The system was popularly called 'leap-frogging’, and hailed as something new in warfare. But it was actually the adaption of modern instrumentalities of war to a concept as ancient as war itself. Derived from the classic strategy of envelopment, it was given a new name, imposed by modern conditions. Never before had a field of battle embraced land and water in such relative proportions. . . The paucity of resources at my command made me adopt this method of campaign as the only hope of accomplishing my task... It has always proved the ideal method for success by inferior but faster-moving forces. ’ ’

Briefly, MacArthur was applying the "indirect approach” method recommended in the months leading up to the World War II by the British military writer Basil Liddell Hart and practised also by Vice-Admiral Halsey inhis advance from Guadalcanal to Bougainville and in the following autumn by Admiral Nimitz in the Central Pacific Area. This also comes out in the following anecdote from Willoughby and Chamberlain’s Conqueror of the Pacific:

"When staff members presented their glum forecasts to MacArthur at a famous meeting which included Admiral Halsey, the newly arrived General Krueger, and Australia’s General Thomas Blarney, MacArthur puffed at his cigarette. Finally, when one of the conferees said, 'I don’t see how we can take these strong points with our limited resources,’ MacArthur leaned forward.

"'Well,’ he said, 'Let’s just say that we won’t take them. In fact, gentlemen, I don’t want them.’

"Then turning to General Kenney, he said, 'You incapacitate them.’”

The results of this method were strikingly described after the end of the war by Colonel Matsuichi Ino, formerly Chief of Intelligence of the Japanese 8th Army:

"This was the type of strategy we hated most. The Americans, with minimum losses, attacked and seized a relatively weak area, constructed airfields and then proceeded to cut the supply lines to troops in that area. Without engaging in a large scale operation, our strongpoints were gradually starved out. The J apanese Army preferred direct assault, after the German fashion, but the Americans flowed into our weaker points and submerged us, just as water seeks the weakest entry to

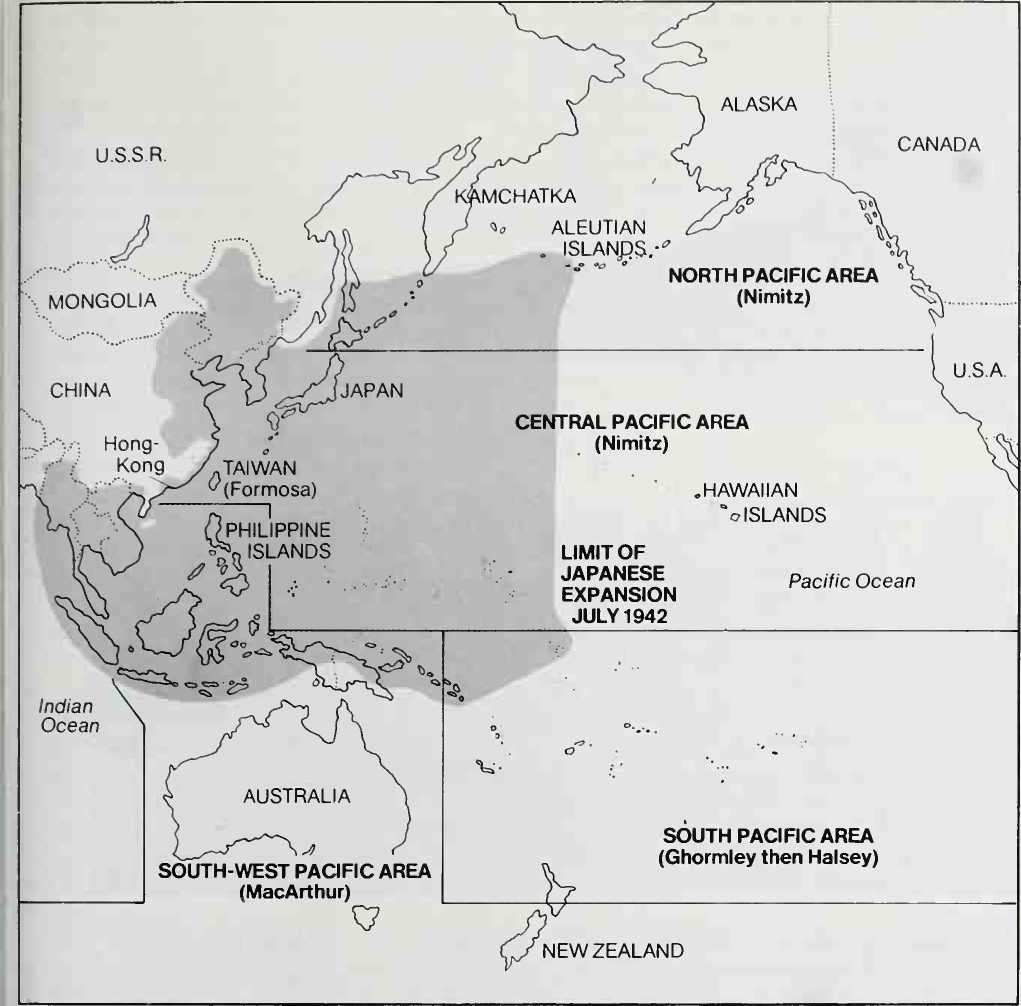

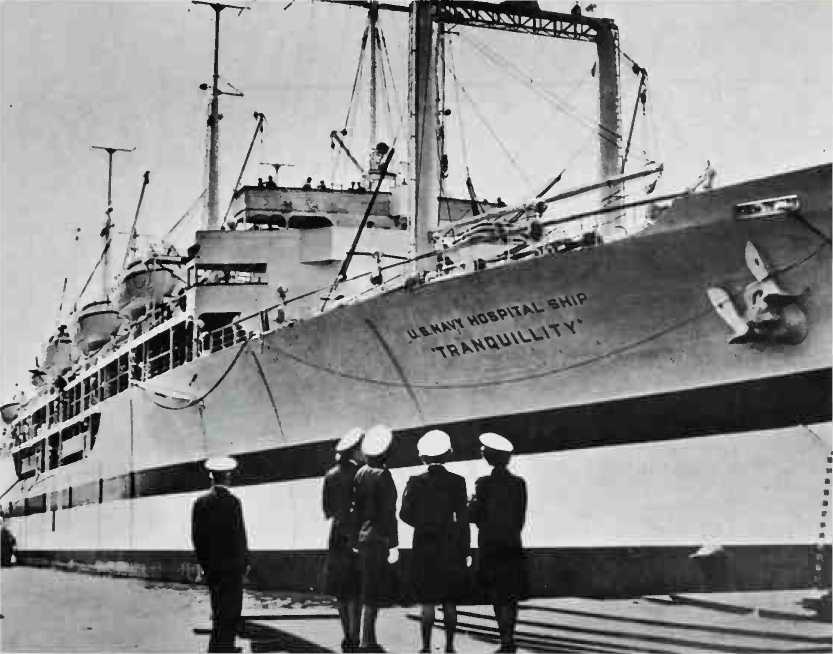

< The Japanese Empire in 1943, showing the vast extent of the "way back" which confronted the Allies in the Pacific-whichever route they finally decided to take. V Floating medical aid for the Allies-essential, considering the distances to be covered: the U. S. hospital ship Tranquillity.

Sink a ship. We respected this type of strategy for its brilliance because it gained the most while losing the least.”

This could not be better expressed; nevertheless, MacArthur’s method demanded perfect collaboration of the land, sea, air, and airborne forces under the command of the C.-in-C. of the SouthWest Pacific theatre of operations. He handled them like some great orchestral conductor.

According to the decisions taken at Casablanca, Nimitz’s ultimate objective was Formosa via the Marshall and Caroline Islands. When he reached here he was to join MacArthur, who would have come from the Philippines, reinforced in the vicinity of the Celebes Sea by the British Pacific Fleet, which meanwhile was to have forced the Molucca Passage. From Formosa, the Allies could sever Japanese communications between the home islands and the newly-conquered empire, as a preliminary to invading Japan itself.

A few weeks after Casablanca, the American Joint Chiefs-of-Staff defined as follows the immediate missions that were to be carried out by General MacArthur and Vice-Admiral Halsey:

"South Pacific and Southwest Pacific forces to co-operate in a drive on Rabaul. Southwest Pacific forces then to press on westward along north coast of New Guinea.”

General MacArthur was therefore empowered to address strategic directives to Admiral Halsey, but the latter was reduced to the men and materiel allotted to him by the C.-in-C. Pacific. This included no aircraft-carriers. In his memoirs MacArthur complains at having been treated from the outset as a poor relation. We would suggest that he had lost sight of the fact that a new generation of aircraft-carriers only reached Pearl Harbor at the beginning of September and that Nimitz, firmly supported by Admiral King, did not intend to engage Enterprise and Saratoga, which were meanwhile filling the gap, in the narrow waters of the Solomon Islands.

Moreover, the situation was made even more precarious because of the new Japanese air bases at Buin on Bougainville and at Munda on New Georgia. This was very evident to Leading Seaman James J. Fahey, who wrote on June 30:

"We could not afford to send carriers or battleships up the Solomons, because they would be easy targets for the land-based planes, and also subs that would be hiding near the jungle. We don’t mind losing light cruisers and destroyers but the larger ships would not be worth the gamble, when we can do the job anyway.”

As we can see, all ranks in the Pacific Fleet were of one mind about tactics.

In the meantime, whilst at Port Moresby General MacArthur was setting in motion the plan which was to put a pincer round Rabaul and allow him to eliminate this menace to his operations, the U. S.A. A.F. was inflicting two very heavy blows on the enemy. After the defeat at Buna, the Japanese high command had decided to reinforce the 18th Army which, under General Horii, was responsible for the defence of New Guinea. On February 28 a first echelon of the 51st Division left Rabaul on board eight merchant ships escorted by eight destroyers. But Major-General Kenney unleashed on the convoy all he could collect together of his 5th AirForce. The Americanbombers attacked the enemy at mast-height, using delayed-action bombs so as to allow the planes to get clear before the explosions. On March 3 the fighting came to an end in the Bismarck Sea with the destruction of the eight troop transports and five destroyers.

Mac Arthur’s biographers write:

"Skip bombing practice had not been wasted. Diving in at low altitudes through heavy flak. General Kenney’s planes skimmed over the water to drop their bombs as close to the target as possible.

"The battle of the Bismarck Sea lasted for three days, with Kenney’s bombers moving in upon the convoy whenever there was even a momentary break in the clouds.

"'We have achieved a victory of such completeness as to assume the proportions of a major disaster to the enemy. Our decisive success cannot fail to have most important results on the enemy’s strategic and tactical plans. His campaign, for the time being at least, is completely dislocated.’ ”

Rightly alarmed by this catastrophe. Admiral Yamamoto left the fleet at Truk in the Carolines and went in person to Rabaul. He was followed to New Britain by some 300 fighters and bombers from the six aircraft-carriers under his command. Thus strengthened, the Japanese 11th Air Fleet, on which the defence of the sector depended, itself went over to the attack towards Guadalcanal on April 8 and towards Port Moresby on the 14th. But since the Japanese airmen as usual greatly exaggerated their successes, and as we now have the list of losses drawn up by the Americans, it might be useful to see what reports were submitted to Admiral Yamamoto who, of course, could only accept them at their face value. Yet it must have been difficult to lead an army or a fleet to victory when, in addition to the usual uncertainties of war, you had boastful accounts claiming 28 ships and 150 planes. The real losses were five and 25 respectively.

But this was not all, for during this battle the Japanese lost 40 aircraft and brought do wn only 25 of their enemy’s. The results were therefore eight to five against them. Had they known the true figures. Imperial G. H.Q. might have been brought to the conclusion that the tactical and technical superiority of the famous Zero was now a thing of the past. How could they have known this if they were continually being told that for every four Japanese planes shot down the enemy lost 15?

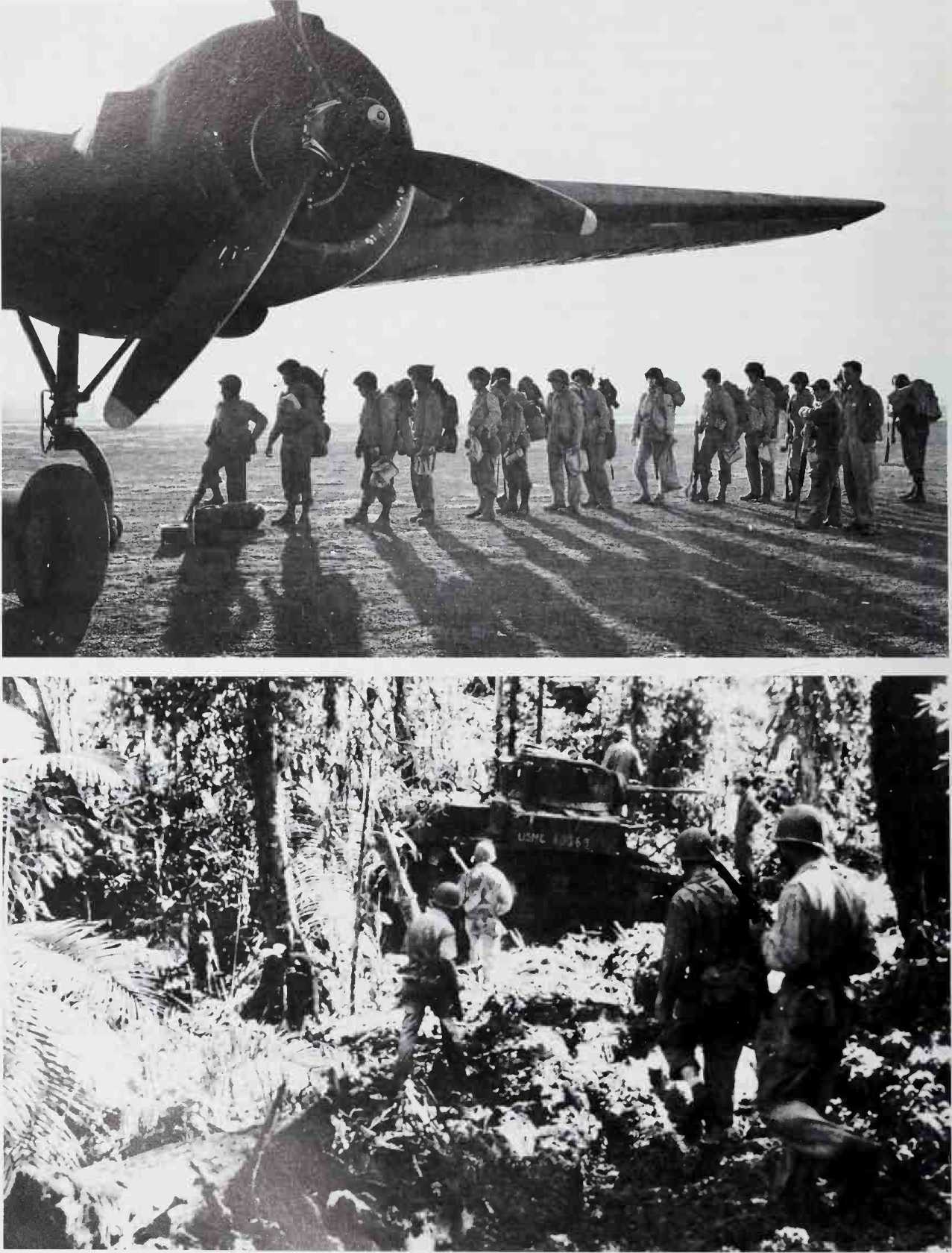

<1 A U. S. troops prepare to board a transport plane in Australia which will take them to battle grounds in New Guinea.

O V Patrol of men moving up through thick jungle.

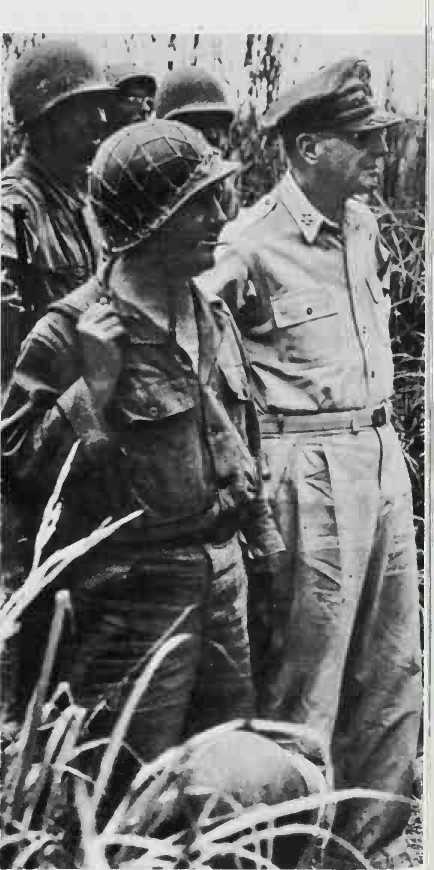

A "I-will-return” MacArthur, in his characteristic braided cap and dark glasses, visits the front.

World History

World History