In the early months of World War II, the United States faced a disaster that loomed as serious as that of Pearl Harbor. The calamity was not developing in the vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, but in the Atlantic, where marauding German U-boats were proving fatal to Alhed shipping.

In February 1942, German submarines sank nearly 500,000 tons of Allied shipping. In March, the figure jumped to over 500,000 tons. In April it dropped to 430,000 tons, but in May the total reached 600,000 tons, and in June, sinkings reached 700,000 tons.

Castastrophe also struck the Normandie, the huge transatlantic liner operated by the French. Scheduled to become a troop transport, the Normandie caught fire at its pier in New York early in February 1942. As firemen poured water on the burning vessel, it listed heavily to one side, then rolled over.

The Normandie never sailed again.

Since the great bulk of ships heading for Europe sailed from New York, port operations there came under close scrutiny. Was information about ship movements being leaked to German submarine commanders? How were German submarines able to refuel and get supplies without returning to their bases in Europe? Who or what might be aiding the U-boats?

Naval intelhgence officials in New York began seeking answers to these questions from all possible sources. Lieutenant Commander Charles Heffen-den, one of the Navy’s most imaginative intelhgence officers, suggested that even leaders of the underworld might be called upon. And when he made this suggestion at a meeting in the office of the New York District Attorney, someone suggested the name of Joseph “Socks” Lanza.

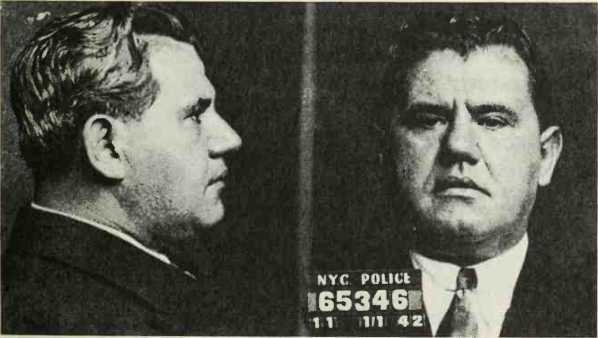

JOSEPH “SOCKS” LANZA AT THE TIME OF HIS ARREST IN NEW YORK IN 1942. (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Anyone who knew anything at all about the New York waterfront in the 1940s knew about Socks Lanza. Bom and raised on the Lower East Side of New York, the oldest of nine children, he had gone to work on the docks at 16. Hard work and hard brawling had brought him to a dominant position in the United Seafood Workers Union by the time he was 35.

Along the way Lanza had compiled a lengthy pohce record. At 17 he was arrested for steahng two barrels of copper tubing. At 19 he was accused of breaking and entering. At 25 he was arrested on a murder charge. There were no witnesses and he was released.

At the time Lanza came to the attention of Naval Intelhgence, he was in serious trouble. The charge this time was extortion. He was due to face trial for demanding kickbacks from waterfront workers and having them beaten when they refused. One parole officer described him as a “ruthless racketeer.”

None of this bothered Naval intelligence officers too much. A lawyer from the District Attorney’s office got in touch with Lanza’s lawyer. Would Lanza, because of his experience and the contacts he had, be wilhng to cooperate with the Navy? It was made clear that Lanza would be cooperating purely as a patriotic service; there were no other considerations involved.

When the question was put to Lanza himself, he quickly agreed to cooperate. “I’ll go along 100 percent,” he said.

The next step was to arrange a meeting between Lanza and Commander Heffenden. The Navy-Mafia partnership was about to be formed. No one had the slightest idea where it was going to lead.

Heffenden was eager to establish whether German submarines were being refueled or resupplied in the coastal waters of the United States. He asked Lanza to start asking questions.

The next day Lanza got down to business. He met with Ben Espy, one of his closest associates, at the ground floor bar of Meyer’s Hotel, Lanza’s headquarters in the Fulton Fish Market area. Lanza told Espy that he had agreed to cooperate with Naval intelligence officials and he asked Espy to help. Espy said he would.

MEYER’S HOTEL, LANZA’S HEADQUARTERS IN THE FULTON FISH MARKET DISTRICT OF NEW YORK. {George Sullivan)

The two men began visiting stores and businesses in the Fish Market area. They asked owners such questions as, “Have you filled any unusually large orders lately?” “Have you noticed unusual activity of any type?”

Lanza and Espy visited the docks where the fishing boats tied up. Lanza was able to talk to the crewmen easily and naturally, as if he were one of them. He asked them, “What’s going on out there?” “Have you seen anything?” “Have you seen any evidence of submarines?” The word was passed to hundreds of fishermen that any sign of suspicious activity should be reported to Lanza.

Through Lanza, Heffenden was able to place agents as workers in the market stalls and on fishing boats as crew members. The boats ranged as far north as Maine and as far south as the Carolinas, with the agents scanning the sea for submarine activity.

While the task of “buttoning up” the port of New York seemed to be moving along well, Lanza admitted that he was limited in what he could accomphsh. He lacked influence outside the Fish Market and the adjacent docks. For instance, along the Hudson River, where the biggest ships that made up the Atlantic convoys docked, Lanza was getting nowhere. The same situation prevailed on the Brooklyn piers. Lanza had few friends in Brooklyn.

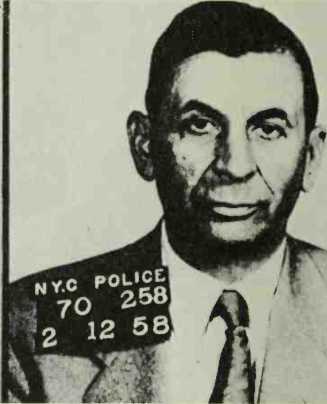

But Lanza suggested a solution—Mafia leader Charles (Lucky) Luciano. He could “snap the whip on the entire underworld,” Lanza said.

The 48-year-old Luciano was a well-known figure. By reputation he was one of the master criminals of the day, known to be wily, greedy, and savagely cruel. One crime reporter of the 1930s said of him, “Like some deadly King Cobra, this droopy-eyed thug coiled himself about the Eastern underworld and squeezed it of its tainted gold.”

In recent years, however, Luciano’s activities had been muzzled. He was serving a prison term of 30 years and had completed only about seven years of the sentence.

Commander Heffenden realized that Socks Lanza had done as much as he could. A total of 49 merchant ships were sunk in April, 1942. The number ballooned to 102 in May. Thousands of crewmen died. Heffenden agreed it would be a good idea at least to talk to Lucky Luciano.

Preparations for the meeting began. Luciano was serving his sentence at Clinton State Prison at Dan-nemora, near the village of Malone in upstate New York. Cold, bleak, and isolated, Dannemora was known as the Siberia of American prisons.

For the convenience of those who were to visit Luciano in an attempt to win his cooperation, he was moved to Great Meadow Prison at Comstock, New York, not far from Albany. Luciano wasn’t told why he was being transferred. But he didn’t care. He was happy to be out of Dannemora.

Other events about to take place would make the Mafia leader even happier. Moses Polakoff, Luciano’s lawyer, convinced Heffenden and other Naval intelligence officers that the man who had the best chance of persuading Luciano to cooperate was a former close associate of his, Meyer Lansky.

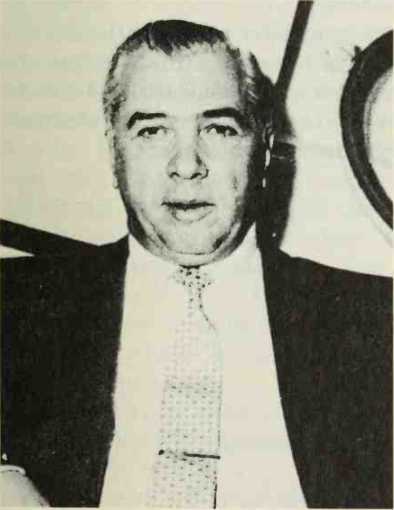

If Luciano was the king of the underworld in the 1940s, Lansky was the prince. Jukeboxes were his domain. He supervised their manufacture, sale, and distribution. Part of every dollar collected from them went to Lansky. Although he had been arrested six times, including once for murder and three times for assaults, Lansky had only one conviction on his record and it was for a minor offense.

In May 1942, the meeting was arranged at Great Meadow Prison. Luciano was not told who his visitors were, and when he was brought into the room where Lansky and Polakoff were seated, he cried out in delight.

For the next half hour, Lansky and Polakoff sought to convince Luciano that he should cooperate with Naval Intelhgence in the war effort. Prison officials had made it clear that no “deal” could be made, that the length of Luciano’s sentence would not be affected, whether he cooperated or not.

But one thing that Lansky and Polakoff could offer was the promise of frequent and confidential visits from his associates. And, as they pointed out, no one expected Luciano to discuss only Naval intelligence matters during such visits.

It was not easy convincing Luciano that he should work with the Navy. There was a problem. The court that had sentenced him had ordered that he be sent back to Italy once he had served his time in prison. If Luciano cooperated with the United States government he would be helping to bring about Italy’s defeat. When he returned to Italy, he would fear for his life.

“I want it kept private, kept secret,” Luciano told Polakoff. “When I get back to Italy, I don’t want to be

CHARLES “LUCKY” LUCIANO COULD “SNAP THE WHIP ON THE ENTIRE UNDERWORLD ” IT WAS SAID. (United Press International)

A marked man.”

Polakoff promised Luciano a guarantee of secrecy.

Then Lansky and Polakoff explained that Joe Lanza had been cooperating with Naval Intelligence and needed help. “Have Lanza come and see me,” Luciano said.

When they met, Luciano told Lanza, “Joe, you go ahead. I will get the word out. Everything will go smoothly.”

He instructed Lanza to get in touch with Joe Adonis and Frank Costello, other Mafia leaders of the day. “Go and see Frank, and let Frank help along,” said Luciano. “This is a good cause.” Lanza

MEYER LANSKY, A KINGPIN OF THE NEW YORK UNDERWORLD, AND A CLOSE ASSOCIATE OF LUCIANO’S. (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Offered to return to Great Meadow and report on how things were working out. “All right, fine,” said Luciano.

Lansky was drawn into the operation, too. He had several meetings with Heffenden and was given a code number as a Naval intelligence contact. In the weeks that followed, Lansky hned up the support of longshoremen and their leaders along the waterfront.

There is no doubt that the Navy’s Mafia connection produced results. Through the final months of 1942 and into 1943, supplies were shipped from the port of New York in an uninterrupted flow. There was no sabotage. There was no labor unrest. There were no stoppages of any kind. There were not even delays.

Longshoremen, truck drivers, and shippers quit talking about the types of supplies going aboard ships. Everyone who worked on the docks was made to realize that enemy agents were seeking that type of information.

During the war years the alliance of American intelligence agents and Mafia leaders was a well-kept secret. It might have remained so for decades had not Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York, on January 3, 1946, granted Luciano his release from prison for the purpose of deporting him to his native Italy.

In a statement released to the press at the time, Dewey said: “Upon the entry of the United States into the war, Luciano’s aid was sought by the Armed

JOE ADONIS IN A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN IN 1956. (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Services in inducing others to provide information concerning possible enemy attack. It appears that he cooperated in such effort. .

Dewey’s statement triggered many questions. Had the Mafia chieftain actually cooperated with the armed services during the war? And if so, what services had he rendered?

In the years that followed, rumor piled upon rumor. Finally, in 1954, Dewey ordered an official investigation of the matter, which estabhshed proof of the cooperation between Naval Intelhgence and Mafia leaders of the 1940s.

When the report was made public, it raised still another question, a moral question. Was it right for forces of law and order to work hand-in-glove with known criminal leaders?

Winston Churchill may have provided the answer when he once said, “If by some stroke of fate the Devil came out in opposition to Adolf Hitler, I should not feel constrained... to make favorable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons.”

World History

World History