Victory at Gallipoli freed thousands of Ottoman soldiers for service on other crucial fronts. With the imperial capital secured, Enver Pasha could finally satisfy his field officers’ urgent demands for reinforcements. The ravaged Ottoman army in the Caucasus received seven infantry divisions to ward off the Russian threat. Cemal Pasha’s forces in Syria and Palestine had been depleted for service in the Dardanelles; four divisions were dispatched to the Levant to restore the Fourth Army to full strength. In Mesopotamia, the Ottomans had fielded ill-trained and poorly supplied troops to face the Anglo-Indian juggernaut. The deployment of two experienced and disciplined divisions from Gallipoli to Baghdad, it was hoped, would shift the balance of power in Mesopotamia in the Ottomans’ favour.1

The Ottoman position in Mesopotamia had deteriorated alarmingly in the aftermath of Suleyman Askeri’s defeat at Shaiba in April 1915. High rates of desertion among Iraqi recruits exacerbated losses through heavy battlefield casualties, leaving Ottoman forces severely under-strength. Ottoman commanders in Mesopotamia had no choice but to go from town to town rounding up deserters under the threat of exemplary punishment. Turkish officers, who regarded Arab recruits as unreliable in the best of circumstances, had few illusions about the military value of deserters reconscripted by force. They would be surprised, however, by the ferocity of Iraqi deserters’ resistance to the recruiting parties sent to reclaim them for the Ottoman war effort.2

Starting in May 1915, the towns and villages of the Middle Euphrates rose in rebellions that ran on for the final two years of Ottoman rule over southern Iraq. The first rebellion broke out in the city of Najaf, a pilgrimage site for Shiite Muslims and a refuge for hundreds of Iraqi deserters who sought asylum within the walls of the shrine city. Iraq’s Shiite communities had grown increasingly disaffected with their Sunni Ottoman rulers, resentful of being drawn into a global war that increasingly disrupted their lives. The clampdown on deserters brought matters to a head, and when the Ottoman governor in Baghdad dispatched a large force to Najaf under an Iraqi officer named Izzet Bey to round up malingerers hiding in the ancient city’s quarters, resentment boiled over into rebellion.

The Ottoman commander announced a three-day amnesty for all deserters who handed themselves in. Given that desertion was punishable by death, Izzet Bey had reason to hope the Iraqis would take advantage of the reprieve and return to military service voluntarily. Yet most of the deserters had fled from Najaf before Izzet Bey’s arrival, and few if any remained in the town to surrender.

After three days, the Ottoman commander decided to send his troops to conduct house-by-house searches. The Ottoman soldiers outraged the conservative women of Najaf by checking under their veils to ensure they were not men hiding in women’s clothes. The townspeople protested this assault against the honour of their women and waited for the right moment to exact their revenge.3

On the night of 22 May 1915, a band of deserters descended on Najaf with their guns blazing and laid siege to the government buildings and army barracks. The townspeople made common cause with the rebels, as deserters from the surrounding countryside converged on Najaf to make a stand against the Ottomans and the global war they had imposed on the unwilling people of Iraq. The battle raged for three days, while the rebels systematically destroyed government offices and records. All communication between Najaf and other administrative centres was severed, as tribesmen in the surrounding countryside cut lines and uprooted telegraph poles. With the surviving Ottoman soldiers and officials besieged in a handful of government buildings, the heads of the town quarters sent criers through the streets of Najaf calling on merchants to open their stores and resume business as usual.

Alarmed, the governor in Baghdad sent a delegation to confer with the townspeople. In a meeting with the town’s leaders, the Ottoman delegates reminded the Najafis that the Ottoman Empire faced a “life or death war” against infidel invaders and that it was every Muslim’s religious duty to assist in this struggle. For their part, the Najafis placed full responsibility for the situation on the Ottomans themselves and stubbornly refused all of the delegation’s requests. In the end, the Ottomans were left to negotiate the safe withdrawal of their besieged soldiers and officials from Najaf and appointed a skeleton administration to keep the semblance of Ottoman rule over the shrine city. However, the people of Najaf took over effective government, with the town gaining a high degree of independence from Ottoman rule.

Encouraged by Najaf’s example, several other key towns in the Middle Euphrates region rose in rebellion against the Ottomans in the summer of 1915. For the people of Karbala’, another Shiite shrine city, rebellion became a matter of civic pride. “Are the people of Najaf better than us, or braver, or more manly?” they asked rhetorically. Once again a group of deserters launched a rebellion on 27 June, burning down municipal buildings, schools, and even a new hospital in Karbala’. Two hundred houses in one of the new quarters of the town were put to the torch, driving the mostly Persian inhabitants to take refuge in the older quarters. Rebels and Bedouin from nearby tribes began to fight amongst themselves over the distribution of plunder as chaos descended on Karbala’. Once again, the Ottomans were forced to negotiate a controlled handover to local rule.4

The Ottomans put up a desperate fight in the town of al-Hilla but found themselves outnumbered by waves of Bedouin and deserters. In al-Sa-mawa, the town’s notables broke their pledge of loyalty, sworn on the Quran to the district governor, when they learned of the approach of British forces in August 1915. A detachment of ninety local soldiers deserted en masse, while the townspeople and Bedouin turned on the Turkish soldiers in their midst. An entire cavalry detachment of 180 men was stripped of their weapons, horses, and clothes and driven from town stark naked. Similar events took place in al-Kufa, al-Shamiyya, and Tuwayrij. In the end, their futile efforts to force deserters to return to active service cost the Ottomans the Euphrates basin.

While the Ottomans faced internal rebellion, the British continued their relentless advance in Mesopotamia. Following its victory at Shaiba in April 1915, the Indian Expeditionary Force had received fresh troops and a new commander, General Sir John Nixon. Under orders to secure the whole of the Ottoman province of Basra, Nixon prepared to advance up the Tigris to the strategic river port of Amara.5

With a population of some 10,000, Amara lay nearly ninety miles north of Basra. After several weeks of preparation and planning, nixon ordered the 6th Division into action under the command of Major General Charles Townshend. To break through Turkish lines north of Qurna, Townshend deployed hundreds of small native river craft as improvised troop transports supported by British steamboats armed with cannons and machine guns. This unlikely armada, dubbed “Townshend’s Regatta”, set off for Amara at dawn on 31 May. Between the artillery bombardment provided by the heavier ships and the massed charges from men in native boats, the British managed to break through Ottoman positions north of Qurna and proceed upriver unopposed by the retreating Ottoman defenders. The advancing British army found itself fighting on friendly territory. Arab villages along the Tigris flew white flags to demonstrate their good intentions towards the new conquerors as the Ottoman retreat degenerated into a demoralized rout.

On 3 June, the advance guard of Townshend’s Regatta reached the outskirts of Amara, where they found an estimated 3,000 Turkish troops attempting to withdraw in advance of the Anglo-Indian army. A British river steamer with a crew of only eight sailors and armed with a 12-pound gun cruised up to Amara unchallenged by the Turkish defenders. The sudden appearance of a boat under the British ensign so demoralized the Turks that eleven officers and 250 men surrendered on the spot, while more than 2,000 Ottoman troops retreated upriver. General Townshend arrived by steamer later that afternoon and raised the Union Jack over the customs house, claiming victory in Amara before the main body of 15,000 troops had even reached the town. The surrender of hundreds of Turkish and Arab soldiers to an advance party they could have overcome easily reflected the collapse of Ottoman morale.6

Following the capture of Amara, Nixon planned to advance up the Euphrates to occupy Nasiriyya and thereby complete the British conquest of the province of Basra. Nasiriyya was a new town established in the 1870s to serve as the market centre of the powerful Muntafik tribal confederation; like Amara, it had a population of some 10,000. Nixon hoped to win over the powerful Euphrates Bedouin tribes by dealing the Turks a defeat and believed that the Ottomans posed a clear and present danger to British troops in Qurna and Basra so long as they held a garrison at Nasiriyya.

Nixon’s forces, under General George Gorringe, began their advance on Nasiriyya on 27 June.

The lower Euphrates was far more treacherous to navigate than the Tigris. In the course of the summer, the river typically dropped in depth from five feet in June to three feet by mid-July and became impassable by August. To secure ships of sufficiently shallow draft, the British were forced to recommission several obsolete paddle steamers to carry their troops upriver towards nasiriyya. One of the British ships, the Shushan, was first commissioned for the relief of General Gordon at Khartoum in 1885. These ancient British steamboats struggled to cross a series of marshlands through ill-marked channels that grew alarmingly shallower week by week.

Despite the outbreak of rebellions in najaf and Karbala’, the Ottomans mounted a spirited defence against the British on the lower Euphrates. With some 4,200 Turkish troops assisted by Bedouin tribesmen in well-defended positions outside Nasiriyya, they initially outnumbered the invaders. Unwilling to proceed against superior numbers, Gorringe called for reinforcements and held his position until the third week of July, when his force reached full strength with 4,600 infantrymen. The diminishing river, parts of which were closed to navigation by late July, had delayed the dispatch of extra troops. With no prospect of further reinforcements by river, Gorringe had to make do with the forces at hand.

The British had mounted preliminary attacks on Ottoman positions outside Nasiriyya in early July. Ali Jawdat, a native of the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, was one of the Ottoman troops resisting the British advance. Jawdat was a professional soldier who had graduated from both the Baghdad military high school and the elite Harbiye military academy in Istanbul before taking his commission in the Ottoman army. Despite his military training, however, Jawdat had mixed loyalties. He had grown disenchanted with the Young Turk government and, like many educated elites in the Arab provinces, aspired to greater Arab autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. He was a founding member of al-Ahd (the Covenant), a secret society established after the 1913 Arab Congress in Paris. The military equivalent of al-Fatat, the Young Arab Society, al-Ahd was particularly strong in Iraq, where it attracted many of the brightest young Arab officers. Like al-Fatat and the De-centralization Party, al-Ahd called for Arab autonomy within a reformed Ottoman state rather than outright independence for fear of European colonial domination. With the outbreak of the Great War, Jawdat threw himself into the defence of the Ottoman Empire against the Entente Powers with all of the loyalty and determination of his Turkish compatriots.

In 1915, Ali Jawdat had served with Suleyman Askeri in the Battle of Shaiba. He retreated with Askeri to Nasiriyya and, after his commander’s suicide, was put in charge of an Ottoman detachment near that town. The Ottomans were assisted by the powerful Bedouin leader Ajaymi al-Sadun, whose tribesmen filled the thin Ottoman ranks confronting the British invaders. The tribesmen asked the Ottomans to provide them with ammunition, and Jawdat was tasked with giving the Bedouin what they needed for the defence of Nasiriyya.

When Gorringe’s forces attacked Turkish lines on the Euphrates, Jawdat watched as the Bedouin irregulars took the measure of the situation and turned against the Ottomans. He saw tribesmen assault Ottoman soldiers to steal their rifles and ammunition. He saw his soldiers fall dead and wounded under intense British gunfire. “The Ottoman soldiers were caught between two fires,” Jawdat later wrote, “from the Bedouin and the British.” Isolated from the main Ottoman lines, Jawdat was himself ambushed by Bedouin

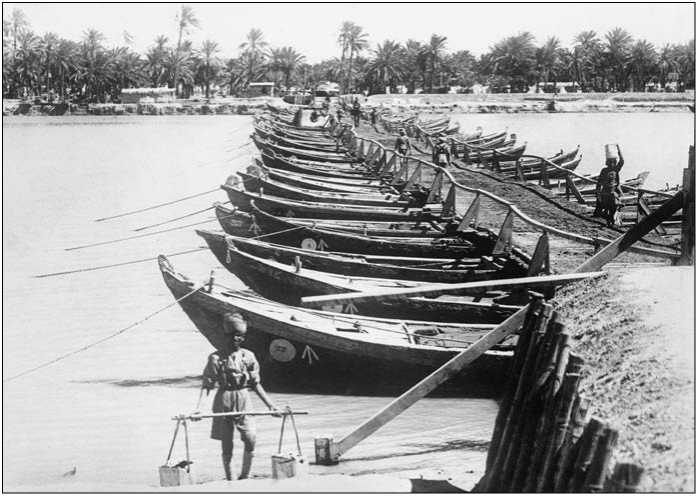

British boat bridge across the Euphrates at Nasiriyya, guarded by Indian soldiers. The Ottomans abandoned Nasiriyya to the British after a day’s intense fighting on 24 July 1915, redeploying their troops to the Tigris for the defence of Baghdad.

Tribesmen, who disarmed and robbed him before he was captured by the British in the village of Suq al-Shuyukh, near Nasiriyya.7

Judging by Ali Jawdat’s experiences, the Ottomans were in no position to retain the lower Euphrates against a sustained attack. There simply were not enough regular Ottoman soldiers to withstand the British, and the Bedouin would side with whomever they believed was stronger. While it was common for Turkish officers to criticize their Arab and Bedouin soldiers as unreliable, Jawdat’s experiences are all the more telling, coming from a native of Iraq with strong Arabist leanings. Jawdat was dispatched to Basra, where he was held as a prisoner until later in the war, when the British had more use for Arab activists.

The British attack on Nasiriyya itself opened on 24 July with salvos of artillery fired from steamships. British and Indian troops then stormed the defenders’ trenches in waves of bayonet charges. The Ottomans held their ground, forcing the invaders to fight for every yard gained. The fighting raged until nightfall. The Turkish defenders, having suffered 2,000 casualties and 950 soldiers taken prisoner, withdrew under cover of darkness. At dawn the next morning, a delegation of townspeople rowed out to the British boats to offer Nasiriyya’s surrender. After suffering heavy casualties of their own, the British were relieved not to have to fight another day.8

With the occupation of Nasiriyya, the British had secured the entire Ottoman province of Basra. Yet General Nixon wanted to press on to take the strategic town of Kut al-Amara. Situated in a bend in the Tigris, Kut was the terminus of the Shatt al-Hayy channel that linked the Tigris to the Euphrates just south of Nasiriyya. British intelligence reported that the 2,000 Ottoman troops who had retreated from Nasiriyya had fallen back on Kut, where they joined forces with a garrison of 5,000 men with the potential to threaten British positions in both Amara and Nasiriyya. Nixon argued that Britain’s control over the province of Basra would not be secure so long as the Ottomans retained Kut.

A growing division was emerging between British officials in London and India on war policy in the Middle East. Although an integral part of the British Empire, India had its own government, headed by the viceroy, Lord Hardinge, and its own army. That army served the empire loyally, dispatching troops to the western front and Gallipoli as well as leading the campaign in Mesopotamia. However, the Government of India needed to preserve a garrison to ensure its own domestic security. With German agents working in Persia and Afghanistan and threatening jihad in the Muslim north-western provinces of India, the viceroy was concerned about preserving a credible deterrent at home. Given India’s importance to the empire, London fully shared the viceroy’s concerns.

The Government of India differed with the British government in London, however, on the deployment of troops. For London, the top priority remained the western front, with Gallipoli a secondary concern and Iraq practically an afterthought. Mesopotamia was far more important to the Government of India than it was to London. Territory gained in Iraq extended the Raj’s own sphere of influence in the Persian Gulf, and many of the political officials attached to the Indian army in Mesopotamia envisaged Iraq one day coming under the Government of India’s control. Thus, the viceroy, unwilling to dispatch significant new forces for fear of compromising the security of India, wanted the return of Indian regiments from the western front to reinforce and extend the Raj’s gains in Mesopotamia. Officials in London, satisfied with the status quo in Iraq, argued instead for a “safe game in Mesopotamia”, in the words of the secretary of state for India, Lord Crewe.9

Following the occupation of Nasiriyya, the Government of India urged London to authorize the occupation of Kut as “a strategic necessity”. The viceroy went on to request the deployment of an Indian army unit, the 28th Brigade then serving in Aden, to reinforce Nixon’s numbers in advance of an assault on Kut. It was a reasonable request, though, given Britain’s tenuous position in South Yemen, not one London was in a position to concede at that moment.10

The truth of the matter was that the i8th Brigade was desperately needed in Yemen to prevent the strategic port of Aden from falling to the Turks. The British assault on Shaykh Said in November 1914 had only served to weaken Britain’s position in Yemen. Officials in India and London had made the decision to destroy the Turkish guns overlooking the entry to the Red Sea without consulting the British Resident in Aden. Colonial officials in Yemen thought the attack ill-advised as it alienated Imam Yahya, the Yemeni ruler in Sanaa, who saw it as an assault on his territory. Although Imam Yahya was nominally an ally of the Ottoman Empire, the British had hoped to preserve cordial relations with him. Those hopes were dashed in February 1915, when the imam wrote to Colonel Harold Jacob, the First Assistant Resident in Aden, to reaffirm his loyalty to the Ottoman Empire and, by implication, his hostility to Britain.11

Turkish forces crossed into the territory of the Aden Protectorate, supported by Imam Yahya, in February 1915. At first, British officials dismissed the Turkish troop movements as posing little or no threat to their position in Aden. Yet, as Ottoman forces in Yemen grew and Turkish agents recruited a growing number of tribal leaders to their cause, the British became increasingly concerned. By June, British intelligence reported Ottoman strength at six battalions (an Ottoman battalion numbered between 350 and 500 men)—Turkish forces outnumbered the British. On 1 July, the Ottomans attacked one of Britain’s key allies in the town of Lahij, less than thirty miles from Aden.12

The sultan of Lahij, Sir Ali al-Abdali, was a semi-independent ruler of one of the mini-states within the British Protectorate of Aden. Though he had been on the throne for less than a year, the British saw him as one of their leading allies in southern Yemen. When Lahij came under threat of Ottoman invasion, the British Resident in Aden mobilized his small and inexperienced garrison to repel the Turkish forces. An advanced unit of 250 Indian troops with machine guns and 10-pound artillery set off for Lahij overnight on 3 July, reaching the town early the following morning. The main body of Welsh and Indian troops followed a few hours later and found themselves marching in the extreme heat of the Yemeni summer. Two of the Welsh soldiers died of “heat apoplexy” on the march, and even the Indian soldiers began to collapse from exposure. The exhausted troops staggered into Lahij before sunset on 4 July to find the town in a state of sheer chaos.

Night fell on Lahij as Arab tribesmen loyal to the sultan fired their weapons into the air. At that moment, a Turkish column entered the central town square, totally unaware of the British presence in their midst. The British captured the Ottoman commander, Major Rauf Bey, and seized a number of Turkish machine guns before the Ottomans had time to react. Once the Turks got the measure of the situation, they went on the offensive, mobilizing a bayonet attack on the British troops. In the chaos, an Indian soldier mistook the sultan of Lahij for a Turk and killed the very ally the British had intended to protect.

The four hundred British troops in Lahij, heavily outnumbered by the Ottomans and their tribal supporters, beat a hasty retreat. Exhausted by their forced march to Lahij and the pitched battle they had fought through the night, the British soldiers only just managed to reach Aden with their forty Turkish prisoners after losing fifty men in combat and another thirty to heatstroke. In addition, the British left behind all of their machine guns, two of their mobile artillery pieces, three-quarters of their ammunition, and all their equipment. And the Turks were left in full possession of lahij, within striking distance of Aden.

The road to Aden lay open to the Ottoman army. Turkish troops advanced from lahij to the township of Shaykh Uthman, just across the harbour from Aden. As Major General Sir George Younghusband, commander of the 28th Brigade, noted, from Shaykh Uthman the Ottomans were “within easy artillery range of the port buildings, ships, residential quarters, Club, Government House, and ships in harbour”. Worse yet, the wells and treatment plant that provided Aden with all of its drinking water were in Shaykh Uthman. Unless the British could drive the Ottomans out of the neighbouring township, their position in Aden was untenable. And the loss of Aden, both for the security of British shipping and for British standing in the Arab world, was inconceivable.13

The Government of India made an urgent request for relief forces from Egypt to reinforce the British position in Aden. The British government swiftly complied, and on 13 July 1915 General Younghusband received his orders to proceed directly to relieve Aden at the head of the 28th Brigade. The troops reached Aden five days later and disembarked at night to hide their arrival from the Turks. On 21 July, British forces crossed the causeway between Aden and Shaykh Uthman and drove the Ottoman troops back to lahij in a surprise attack. While British casualties were light, the Ottomans lost some fifty men killed and several hundred taken prisoner.

Younghusband fortified the British position in Shaykh Uthman and decided to hold his ground. Having regained control over Aden’s water supply, he refused to extend his lines or put his men in jeopardy by going on the offensive. “It is too hot for one thing and for another it does not seem wise at this juncture to leave a strong fortress to go forth on precarious adventures in the desert,” he wrote to the British commander in chief in Egypt. This was the situation at the end of July when Lord Hardinge requested that the 28th Brigade be dispatched to the Mesopotamian front to assist in the conquest of Kut al-Amara. Needless to say, the War Cabinet in London denied the viceroy’s request. With an estimated 4,000 Ottoman troops in Lahij, the

Aden garrison of 1,400 men was even then insufficient to hold the strategic port without reinforcements—an uncomfortable situation that would endure until the end of the war.14

To make matters in Yemen worse, as in Gallipoli the Turks had asserted control over the front. The British had proved too weak to protect the rulers and territory of their Aden Protectorate. Even more than the loss of territory, the loss of face in the Arab and Muslim world concerned officials in London, Cairo, and Simla. As Acting British Resident in Aden Harold Jacob concluded, Britain’s “failure to defeat the Turks before Aden was the supreme cause of our loss of prestige in the country”. Ever conscious of German and Ottoman jihad propaganda, the British felt their failings in Aden were another gain for their enemies and undermined the Entente Powers’ position in the Muslim world more generally.15

Even without the benefit of reinforcements in Mesopotamia, General Nixon had persuaded the viceroy that the Indian army could take Kut al-Amara with the forces already at its disposal. The Turkish army in Iraq, Nixon argued, was in disarray after a string of battlefield defeats. The Anglo-Indian troops had gained in experience and won the self-confidence that came with repeated victories. Given time to recover from their fevers (even General Townshend succumbed to illness after the conquest of Amara and had to return to India to convalesce), Nixon was confident that his soldiers could resume their seemingly unstoppable advance up the Tigris. He proposed waiting until September 1915 to launch the assault on Kut, and Lord Hardinge gave his approval for the next stage of the Mesopotamia campaign.

The conquest of Kut was to be led by General Townshend, whose “regatta” had so effortlessly taken Amara. Yet Townshend had grave reservations about extending British lines. “Where are we going to stop in Mesopotamia?” he fretted. His concerns were well founded. After nearly a year in Mesopotamia, the Indian army needed reinforcements, and Townshend worried about his supply lines as British forces advanced deeper into the region. Each conquest extended lines of communication that were entirely dependent on river transport. Yet the riverboats available to the Indian army were not fit for purpose. Doubling the length of the supply line from Basra without adequate transport would place the entire expeditionary force at risk. While convalescing in India, Townshend met Sir Beauchamp Duff, the commander in chief of the Indian army, who pledged “not one inch shall you go beyond Kut unless I make you up to adequate strength”. On this understanding, Townshend accepted his orders from Nixon to lead the advance on Kut and began his march upriver on 1 September.16

Townshend had more grounds for concern than he realized at the time. The Ottomans had appointed an energetic new commander to head their forces in Mesopotamia. Nurettin Bey was a fighting general who had served in the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 and suppressed insurgencies in Macedonia and Yemen before the outbreak of the Great War. As one military historian concluded, the multilingual nurettin (who spoke Arabic, French, German, and Russian) was “exceptionally talented”. Tasked with protecting Baghdad from the Indian army, nurettin worked tirelessly to rebuild his depleted divisions and managed to draw new units to Mesopotamia. A dangerous new dynamic was transforming the Mesopotamian front to Britain’s disadvantage: Ottoman numbers were expanding while British forces were being progressively depleted.17

British and Australian airmen took to the skies over the Tigris to assess Turkish positions around Kut al-Amara. The aerial reconnaissance was of immense value to Townshend and his officers in planning their offensive. They saw where Turkish forces were entrenched and could plot the locations of artillery batteries with a higher degree of precision than for any previous attack in Mesopotamia. Yet it was dangerous business. The aircraft were prone to breaking down in the heat and dust of summer, while Turkish sharpshooters inflicted serious damage on planes intent on getting a closer look at their positions. On 16 September, a British plane was forced to land behind Ottoman lines, where the Australian pilot and his English observer were taken prisoner.18

Aerial reconnaissance showed that the Turks had established strong positions seven miles downstream from Kut at a position known as al-Sinn. Their trenches ran for miles on both sides of the Tigris between impassable marshlands, forcing the British attackers either to risk a frontal assault across open terrain or to march for miles around marshlands to outflank Ottoman lines. An obstruction laid across the river prevented British ships with artillery mounted on their decks from getting through. nurettin had assured his troops that their positions were impregnable and that the British would not pass.

The British estimated total Ottoman strength in al-Sinn at 6,000 infantry, of which only one-quarter were Turks and three-quarters were Arabs. Townshend was confident that his force of 11,000 men, reinforced with artillery and machine guns, was more than sufficient to overcome Ottoman defences. Some of his junior officers were less sanguine. “Having seen enemy’s position,” Captain Reynolds Lecky wrote in his diary, “very big, strongly entrenched and well wired in, more dirty work for some of us.”19

British troops moved into position overnight to launch a multi-front attack on Ottoman lines in the early morning hours of 28 September. The plan called for precision manoeuvres, with some units drawing fire from the Ottoman front while others circled around to outflank Ottoman positions. However, in the predawn dark, several of the British columns got lost and delayed among the marshes. Forced to attack in broad daylight, the British not only lost the crucial element of surprise but also found themselves exposed to heavy artillery and machine-gun fire. “Had a beastly day,” Captain Lecky recorded in his diary, “lost a lot of men. The Turks fairly caught us in one place with their shrapnel. They had evidently ranged it to the foot and kept putting them right on top of us. . . . One of our machine-guns about five yards from me got a direct hit which smashed the mounting to pieces. Spent all night digging in and by daybreak we were dead tired.” As Lecky’s account confirms, Ottoman forces put up a determined defence of their lines and inflicted heavy casualties on the exposed British attackers. The two armies battered each other from dawn to sundown. While the exhausted British forces settled in to hold their gains overnight, the Ottomans silently withdrew to the town of Kut. Captain Lecky noted with respect, “The Turks cleared in the night, a very masterly retreat, not a thing left.”

The British took several days to advance from the abandoned Ottoman lines at al-Sinn to the town of Kut. The barrier the Ottomans had erected across the river obstructed shipping long after it had been breached, and the low water level in the river further hindered navigation. There were also far more wounded than British planners had allowed for, and they needed to be transported downstream to medical facilities in Amara and Basra before the British renewed hostilities with the Turks for control of Kut.20

In the end, the Turks did not force the British to fight further for Kut. British aerial reconnaissance reported on 29 September that the Ottomans

Had abandoned the town and completed an orderly retreat upriver towards Baghdad. On the one hand, this was good news, as the British could occupy Kut al-Amara unopposed. Yet in victory Townshend had failed: the Ottomans had slipped through his net and retreated with their artillery and most of their forces intact. Each British failure to surround and destroy the Ottoman army in Mesopotamia gave the Turks the opportunity to regroup, drawing the Indian army ever deeper into Iraq and further extending its lines of supply and communications. The Indian Expeditionary Force grew more vulnerable with every battle it won in Iraq.

The British victory at Kut in October 1915 coincided with the growing recognition in London that the Dardanelles campaign had failed. Many politicians feared the adverse consequences of a British defeat in Gallipoli for their standing in the Muslim world. The British cabinet believed that failure in the Dardanelles would deal their enemies a propaganda victory for their jihadist politics. Inevitably, some politicians came to see the occupation of Baghdad as a remedy for the reputational risks of evacuation from Gallipoli.

The commanders in the field were of two minds. General Nixon believed not only that his forces could take Baghdad but that their position in Mesopotamia would not be secure until they did. General Townshend, who had led the 6th Poona division to victory in Amara and Kut, argued that the British should consolidate their hold over the extensive territory they had already conquered. While his soldiers could quite possibly take Baghdad from the Turks, they would need significant reinforcements to hold the city and to assure lines of communication stretching hundreds of miles along the fickle Tigris from Baghdad to Basra. The operation required no less than two full divisions of fresh troops, Townshend maintained.

On 21 October, the dardanelles Committee, the British government’s war committee for operations in the Middle East, debated options in Mesopotamia. Lord Curzon took Townshend’s line that Britain would do best to consolidate its gains from Basra to Kut. An influential troika of ministers, including Foreign Secretary Lord Grey, First Lord of the Admiralty Arthur Balfour, and Winston Churchill (demoted after Gallipoli to the minor cabinet post of chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster but still a powerful voice in government), agreed with Nixon and called for a full occupation of Baghdad. Lord Kitchener, the military man, advocated a middle line between these two positions, calling for a raid to destroy Ottoman forces in Baghdad followed by a strategic retreat to more defensible British positions. “If Baghdad is occupied and Gallipoli evacuated,” Kitchener argued, “a force of 60-70,000 Turks might be sent” to retake Baghdad, and Townshend would need several divisions to retain the city against such an army. Perhaps Kitchener’s influence over the cabinet was waning after repeated failures in the Dardanelles, for he gathered little support for his position. As the official historian of the campaign concluded, the politicians saw in Baghdad an opportunity “for a great success such as we had not yet achieved in any quarter and the political (and even military) advantages which would follow from it throughout the East could not easily be overrated”.21

In the end, the Dardanelles Committee was unable to come to a decision. In not explicitly forbidding an advance on Baghdad, however, it tacitly approved whatever action the most determined might pursue. And the most determined—General Nixon, Viceroy Lord Hardinge, and their supporters in the cabinet, Grey, Balfour, and Churchill—were for taking Baghdad. The secretary of state for India, Austen Chamberlain, conceded and, with the cabinet’s blessing, sent a telegram to Lord Hardinge on 23 October giving General Nixon authorization to occupy Baghdad and promising to dispatch two Indian divisions from France to Mesopotamia as soon as possible.22

For the first time since the outbreak of the war, the Ottoman army in Mesopotamia had the commanders and troops with which to confront the Anglo-Indian invaders. Ottoman forces in Mesopotamia and Persia were reorganized into the Sixth Army in September 1915, and the venerable Prussian field marshal Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz was appointed commander in chief. Aged seventy-two when he took up his appointment, Goltz Pasha and his German staff officers received a hero’s welcome on arrival in Baghdad in December 1915.

The Prussian commander enjoyed important advantages over his predecessors in Iraq. The Turkish generals under his command had gained valuable experience in fighting against the British, and with the arrival of two new divisions in Mesopotamia, the Sixth Army was reaching parity with British forces in Mesopotamia. The battle-hardened Ottoman 51st Division, composed entirely of Anatolian Turks, was a more disciplined force than the Indian army had yet encountered in Iraq.

The arrival of these new forces in the autumn of 1915 made quite an impression on the people of Baghdad, as one resident recalled: “The town crier went through the markets of al-Kazimiyya [a district of Baghdad] calling on the people to gather on the riverbank to welcome the Turkish forces that were arriving. When the people went out they found the river covered in an amazing number of rafts, each filled with soldiers. The troops disembarked from their rafts and set off marching in ranks to music. The people raised their voices in cheers and the women ululated to greet the soldiers.” The balance of power was shifting in Mesopotamia, as the Ottomans came to enjoy both a numerical and a qualitative advantage over the battle-weary ranks of the Indian army.23

Townshend’s task was to take Baghdad with the forces under his command—in all, some 14,000 men. A further 7,500 British troops were distributed among garrisons stretched from Basra to Kut al-Amara on the Tigris and to Nasiriyya on the Euphrates. The promised Indian divisions were not expected to reach Basra before January 1916. While the string of victories had certainly given the Anglo-Indian troops confidence, the months of marching and fighting, compounded by the hardships of the Iraqi summer and the prevalence of disease, had taken their toll. Many of the British units under Townshend’s command were well under-strength, and he was beginning to have concerns about the loyalties of his Indian Muslim soldiers.

Ottoman propagandists actively played on Islamic loyalties to try to split British ranks. The government press in Baghdad printed leaflets in Hindi and Urdu calling on Indian Muslims to abandon the “army of disbelievers” and join their brothers in faith in the Ottoman army. They reminded Muslim soldiers that Salman Pak, where the Turks had entrenched for the defence of Baghdad, was revered as the burial place of one of the Prophet Muhammad’s most faithful companions, Salman (pak means “pure” in Persian and Turkish—thus, “Salman the Pure”).24

These leaflets had some effect as the British generals detected a growing reticence among the Muslim sepoys to advance against the “holy place” of Salman Pak. Isolated cases of mutiny had already been reported. In October 1915, Captain Lecky recorded that four Muslim soldiers on picket watch close to Turkish lines had cut the throat of their commander and fired on British positions before crossing over to Ottoman lines. After that incident, the 20th Punjabis were dispatched for service in Aden “owing to desertions”. The British feared further mutinies in response to Ottoman propaganda focusing on the shrine of the Prophet’s companion. In order to diminish the religious significance of the place, the British systematically referred to Salman Pak by its classical Sassanid name, Ctesiphon.25

At the very heart of the Ottoman defences lay the Arch of Ctesiphon, a colossal monument dating from the sixth century that even today remains the largest brick vault ever constructed. For months, the Turks had been preparing their positions around the great arch. Their front line stretched over six miles, broken up by fifteen earthwork fortresses, or redoubts, armed with cannons and machine guns. A complex network of communication trenches enabled the movement of men and supplies to and from the front, and enormous water jugs installed at regular intervals ensured defenders would not go thirsty. About two miles behind the front line, another well-constructed set of trenches defined the Turkish second line. The crack 51st Division was held in reserve in this second line of trenches. These defences were as close to impregnable as the Ottoman commander Nurettin and his officers could manage in the time between their retreat from Kut in October 1915 and the British advance the following month.

British commanders had no reliable information on Ottoman forces defending Baghdad. Estimates of Turkish numbers ranged from 11,000 to 13,000 in the lead-up to the assault on Salman Pak. In early November, Nixon and Townshend began to receive contradictory reports about Ottoman reinforcements sent from Syria or the Caucasus to Baghdad but discounted them as unreliable. To compound their uncertainty, Nixon had ordered a halt to reconnaissance flights over enemy lines on 13 November after losing another of his precious airplanes to enemy fire. Nixon and Town-shend assumed that either their numbers were at parity with Ottoman forces or the Ottomans slightly outnumbered them. However, their experience of Turkish defenders collapsing under pressure gave British commanders confidence that they could prevail even against slightly superior numbers.26

On the eve of battle in November 1915, Townshend ordered two aircraft aloft for a last, long-range overview of the enemy’s positions. The first pilot returned safely, reporting no changes in Ottoman lines. The second pilot, flying to the east of Ctesiphon, was troubled by significant changes on the ground and evidence of considerable reinforcements. As he circled back for a closer look, Ottoman troops shot holes in his engine, forcing him to land behind enemy lines, where he was taken prisoner. Though the pilot refused to answer his captors’ questions, they took the map on which he had marked the position of the 51st Division—the first reliable intelligence on Ottoman reinforcements. As a Turkish officer recorded, “The map containing this priceless information fell, not into the hands of the enemy commander. . . but into those of the Turkish commander.”27

The downing of the British plane not only prevented Townshend from learning that his troops were dangerously outnumbered by an Ottoman force of more than 20,000 men but also did a great deal to raise morale among the Turkish troops. “This little event was taken for a happy omen that the luck of the enemy was about to change,” the Turkish officer noted. And so it was.

In the early morning hours of 22 November, the British moved against the Ottoman front line. Four columns of troops advanced under the mistaken belief that they still enjoyed the element of surprise. The illusion was quickly shattered as the defenders opened fire with machine guns and artillery as the British came into range. “Almost directly under fire from guns,” Captain Lecky recorded in his diary, along with the names of his comrades killed in the first onslaught. “Rifle fire incessant until about 4 p. m. Fighting very severe.”

The British and Ottomans engaged in bayonet charges and hand-to-hand combat for hours before the British finally took the Ottoman front-line trenches. Yet no sooner had the British secured the front than the Ottomans mounted a fierce counter-attack with some of their most experienced troops from the 51st Division. The fighting raged well into the night as the casualties mounted on both sides. “A dreadful day,” Lecky concluded, “dead and wounded everywhere and no means of getting them in.” By the end of the first day of fighting, British losses reached 40 percent of their forces, and the Ottomans lost nearly 50 percent of theirs, leaving commanders on both sides profoundly depressed.28

The fighting continued for a second day on 23 November, with both armies facing a growing crisis with their wounded troops. “All day getting in wounded,” Captain Lecky recorded, “hundreds still un-treated, no stretchers, no morphia, no opium, nothing for them.” Still the two sides battled at close quarters deep into the night. “About 10 p. m.,” Lecky recorded, “while

Turkish infantry in Mesopotamia launching a counter-attack. The Ottomans deployed experienced front-line troops for the defence of Baghdad who surprised the British invaders with the intensity of their counter-attacks. Both sides suffered casualties of between 40 and 50 percent in the decisive battle of Salman Pak in November 1915.

Creeping along the Dorsets’ trench we were heavily attacked. Wounded had an awful bad time, they were still lying out in open behind trenches. Our guns were close up, firing point-blank, and one could hear the [Turkish] officers urging the enemy on, a devil of a night."

For three days, the Ottomans held the Anglo-Indian army at bay. The British managed to retain the Ottoman front line but lacked the troops to overwhelm the defenders in the second line of trenches. The number of untreated wounded posed a growing problem for the British in particular (the Ottomans were able to evacuate their wounded to nearby Baghdad). The British had not anticipated such heavy casualties and were woefully unprepared to treat the thousands of grievously injured soldiers. Captain Lecky described “men with shattered legs and no legs at all being brought in on great coats. Their sufferings were beyond description." The relentless fighting, the piteous groans of the wounded, and the rumours of Turkish reinforcements combined to sap the morale of Townshend’s army.

By 25 November, Townshend and his commanders recognized their position was untenable. The Indian army was outnumbered and overextended.

They had gone to battle with a fixed number of troops and no reserves to back them up. The earliest reinforcements would not reach Mesopotamia before January. They had to preserve as many able-bodied soldiers as possible to defend British positions between Basra and Kut al-Amara and urgently needed to evacuate the wounded. Townshend required every riverboat at his disposal to carry the thousands of wounded downstream, leaving the able-bodied, exhausted after three days of intense fighting, to undertake every soldier’s nightmare: a retreat under enemy fire.

The British retreat from Salman Pak marked a decisive turning point in the Mesopotamia campaign. The Ottomans were quick to take the offensive—both on the battlefield and in the propaganda war.

Relations between the Ottomans and their Iraqi citizens had reached a low point with the British advance up the Tigris in September and October 1915. The residents of Baghdad had openly begun to mock the caliph, Sultan Mehmed Re§ad, and his armed forces, chanting,

Rejad, you son of an owl [a bird of misfortune], your armies are defeated

Rejad, you ne’er-do-well, your armies are on the run.29

With the towns of the Middle Euphrates growing bolder in their revolt against the Ottomans and the natives of Baghdad increasingly defiant, the Ottomans decided to relaunch their jihad efforts, this time targeting the disaffected Shiite population of Iraq. The Ottoman government played on popular religious enthusiasm by unfurling “the Noble Banner of Ali” to win the support of the Shiites of Iraq for the unpopular war effort.30

Ali ibn Abi Talib was the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the fourth caliph of Islam. Since the first century of Islam, Shiite Muslims have revered the Caliph Ali and his descendants as the only legitimate leaders of the Muslim community (indeed the word “Shiite” derives from the Arabic name for Ali’s supporters, ShiatAli, or the “Party of Ali”). This made Shiites unresponsive to the Sunni Ottoman sultan’s decrees as caliph, or spiritual leader of the global Muslim community.

The Ottomans hoped to mobilize the Iraqi Shiite community through its reverence for the Caliph Ali to join the fight against the British invaders.

Towards this end, they engaged in the outright chicanery of parading an impressive flag as a relic endowed with special powers associated with the Caliph (or in Shiite nomenclature, Imam) Ali. Government agents circulated among the shrine cities of Shiite Iraq, describing the banner as a sort of secret weapon that had brought faithful Muslim generals victory over infidels in every battle fought under Imam Ali’s standard.

The Noble Banner of Ali was entrusted to a high-ranking Ottoman official who, accompanied by a detachment of cavalry, carried it from Istanbul to Iraq in the autumn of 1915. It was rumoured that the delegation distributed gold to secure the support of the more materialist Bedouin tribal leaders along the way. The delegation went first to the city of Najaf, burial place of Imam Ali and the political centre of Shiite Iraq. Revolt had first broken out there against the government in May 1915. The Ottomans planned to unfurl the banner over the mosque in which Imam Ali is buried, in Muharram, the holiest month of the Islamic calendar to Shiites.

The banner was revealed to enthusiastic crowds in Najaf on the eleventh day of Muharram, which corresponded with 19 November on the Western calendar. Shiite notables waxed eloquent on the renewed call for jihad against the British infidels, or “worshippers of the cross”—a reference not just to the British soldiers’ Christian faith but to the medieval wars of the Crusades that had pitted Christians against Muslims in the eastern Mediterranean.

The fortunes of war favoured the myth of the banner. In the ten days it took for the flag to travel from Najaf to Baghdad, the Ottoman army achieved its first victory against the British. The deputy governor in Baghdad was quick to draw the connection in his speech to the townspeople who turned out to welcome the mystical flag. “No sooner had this Noble Banner left Najaf than the enemy was brought to a halt and failed in his grand attack on Salman Pak,” Shafiq Bey intoned, and the crowd roared its approval. The anxious citizens of Baghdad took comfort in the Ottoman army driving the British away from their city and dared to hope for victory—even if it took divine intervention.

While the authorities raised the Noble Banner of Ali in Iraq, a group of Ottoman officers had resumed their jihad in the Libyan Desert. In May 1915, Italy had entered the Great War in alliance with the Entente

Powers. The Young Turks seized the opportunity to subvert Italy’s precarious position in Libya, which the Ottomans had been forced to cede in 1912. By promoting religious extremism in the frontier zone between Libya and Egypt, the Ottomans and their German allies hoped to undermine both Britain and Italy through their North African colonies. Their partner in jihad was the head of the Sanussi religious fraternity, Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif al-Sanussi.31

Sayyid Ahmad had led Sanussi forces in the Italian-Turkish War of 1911. The Sanussi order was a powerful Sufi (or mystical Islamic) brotherhood based in Libya, with a network of lodges across North Africa and a membership spanning the Arab world. Leader of the Sanussi brotherhood since 1902, Sayyid Ahmad had continued the fight against the Italians even after the Ottomans ceded Libya to Rome’s rule in 1912. His standing as head of a transnational Muslim mystical order and his reputation for fighting foreign invaders made Sayyid Ahmad a powerful partner for the Ottoman jihad effort.

In January 1915, two influential Ottoman officers set out on the perilous journey from Istanbul to Libya. The head of mission was Nuri Bey, brother of the minister of war, Enver Pasha. He was accompanied by Jafar al-Askari, a native of the northern Iraqi city of Mosul. A graduate of the Ottoman military academy who completed his training in Berlin, Askari was also a founding member of the Mosul branch of the secret Arabist society al-Ahd. Like many of his Arabist fellow officers, he was a staunch opponent of the British and French in their quest to conquer and carve up the Ottoman and Arab lands. He would defend Ottoman territory against European encroachment, but he would also defend Arab rights against Turkish domination. Jafar al-Askari was comfortable with his mission to assist the Sanussi.

Nuri and Jafar went first to Athens, where they purchased a small steamship and a quantity of arms to take with them to Libya. To elude enemy warships in the eastern Mediterranean, they made their way to Crete to await favourable conditions for a dash to the Libyan coast. They instructed their skipper to convey them to an isolated stretch of beach between the Libyan town of Tobruk and the Egyptian border town of Sallum. They landed in February 1915 at a point on the Libyan coast some twenty miles from the Egyptian frontier and immediately made contact with Sayyid Ahmad.32

The Ottoman officers found the Sanussi leader preoccupied with a difficult balancing act. On the one hand, he needed to preserve good relations with the British in Egypt to keep open the only supply route for his movement, which was hemmed in by Italian enemies to the west and the French in Chad to the south. The British openly courted Sayyid Ahmad to keep the peace on Egypt’s western frontier. Yet the Ottomans were there to remind him of his duty, as an influential Muslim leader, to promote jihad against foreign invaders. “There is no doubt that in his heart he favored the Ottomans,” Jafar al-Askari claimed, “but it always proved impossible to dispel that Arab leader’s general mood of gloom, suspicion and apprehension.”

The Sanussi tribesmen made for a highly irregular army. Some were organized along tribal lines. Others were drawn from theology schools, including the four-hundred-man elite Muhafiziyya corps of religious scholars who served as Sayyid Ahmad’s bodyguard. “Their constant recital of the Qur’an in a loud, low throaty drone through their period of guard duty presented an awesome spectacle of piety which deeply struck everyone who witnessed it,” Jafar al-Askari recalled. It was up to him, along with some twenty Arab and Turkish officers, to organize these irregulars into a standard military force before unleashing them against the British in western Egypt. In light of their battlefield performance, even the British would later acknowledge that Askari “was an excellent trainer of men”.33

After months in eastern Libya, the Ottoman commanders were impatient for the Sanussi to launch an attack. Frustrated by Sayyid Ahmad’s indecisiveness, Nuri Bey prompted some of the Sanussi leader’s subalterns to lead a raid on British positions in late November 1915. Sayyid Ahmad was furious that his officers had acted without his authority, but the Ottomans were delighted when, on 22 November, the Sanussi attacks drove the British into retreat. The British abandoned their frontier posts at Sallum to fall back to Marsa Matruh, 120 miles to the east.

The Sanussi movement gained momentum as Bedouin of the Awlad Ali tribe joined in the attack on British positions. A detachment of the Egyptian Camel Corps crossed lines to join the growing Arab movement against the British. Fourteen native officers of the Egyptian coastguard and 120 men deserted to the Sanussi cause with their arms, equipment, and transport camels. Following these defections, the British withdrew Egyptian artillery units of “doubtful” loyalty from Marsa Matruh as a precaution. These developments encouraged Ottoman aspirations to provoke a broader Egyptian uprising against the British and raised morale among the Sanussi fighters.

The British moved quickly to contain the threat posed by the Sanussi jihad. Some 1,400 British, Australian, New Zealand, and Indian troops were dispatched to Marsa Matruh to serve in the newly formed Western Frontier Force, reinforced by artillery, armoured cars, and aircraft. Their mission was to re-establish British control over the Libyan frontier and to prevent Sayyid Ahmad from inciting a broader revolt in Egypt and the Arab world in the dangerous month of December 1915, when the British were feeling particularly vulnerable in both Gallipoli and Mesopotamia.

On 11 december, units of the Western Frontier Force set out from Marsa Matruh to attack Arab forces encamped sixteen miles to the west. As the British infantry drew within range of their guns, the Sanussi opened fired, pinning the foot soldiers down until their artillery and cavalry could relieve them. The fighting went on for two days, the Arabs attacking with great discipline. Scattered by accurate cannon fire, the tribesmen were finally driven back by the Australian light Horse on 13 december. Both sides suffered relatively light losses in their first skirmish, though the head of British intelligence for the Western Frontier Force was killed.34

The British launched a second surprise attack on Sanussi positions at dawn on Christmas day 1915. The sudden appearance of enemy forces provoked panic among the Arab tribesmen. By the time Jafar al-Askari reached the front, he found his soldiers, in his words, “retreating in a manner suggesting more a rout than an orderly withdrawal”. Working to re-establish discipline in his lines, Askari made a grim assessment of the situation at sunrise: “I could see that our position was surrounded by the enemy on all sides.” He could make out two infantry battalions approaching from the west, a large cavalry force on his right flank, and a large column marching down the road from Marsa Matruh in his general direction, while a British warship moored in the bay fired with increasing accuracy on Arab positions. “It was a thoroughly terrifying sight,” Askari confessed, “and I had the greatest difficulty in keeping the men in their positions.”

In a day of intense fighting, the British drove Arab forces into retreat from their hilltop positions. Jafar al-Askari narrowly escaped capture, though the new Zealanders seized his tent and all of his papers. “At sunset we beat a retreat,” Askari recorded, “abandoning our dead and wounded to the mercy of the enemy, having exhausted or lost all our food and ammunition.” The defeat took its toll on the Arab fighters’ morale, and the Ottoman officers recorded a “steady trickle of desertions”.

The British had secured victory, but they had yet to destroy the Sanu-ssi army, which had grown to some 5,000 men. With his Arab tribesmen in possession of the coastline from Sallum to the British garrison town of Marsa Matruh, Sayyid Ahmad enjoyed some significant advantages. German submarines plied the Libyan and Egyptian coastlines, providing guns, ammunition, and cash to the Ottoman officers advising the libyan campaign. Moreover, news of the British evacuation from Gallipoli and reversals in Mesopotamia had many in Egypt looking to the Sanussi uprising with hope for deliverance from a hated British colonial order.

British war planners were far more concerned about the reversals they had suffered in Mesopotamia than the challenges posed by a handful of Sanussi zealots in Egypt’s Western Desert. The unbeaten 6th Poona Division had been turned back at Salman Pak and driven into a retreat under fire. And the British commanders in Mesopotamia lacked the forces to protect Townshend’s defeated army. Until the promised reinforcements reached Basra, the British barely had enough troops to hold the towns they had occupied in the first year of campaigning.

After a relentless week of marching under fire, the weary Indian and British soldiers filed into the familiar streets of Kut al-Amara on 2 December. Situated in a horseshoe bend of the Tigris, Kut was a prosperous town, the centre of the local grain trade with an international commerce in liquorice root. Its mud-brick courtyard houses stood several stories tall, with intricate carved wooden decorations. Among its larger public buildings were government offices, two mosques, one with a fine minaret, and a large covered market that the British requisitioned to serve as a military hospital. A mud-brick fortress dominating the river to the north-east of the town became the cornerstone of the British line of defence stretching across the neck of the peninsula on the left bank of the Tigris.

Some of Townshend’s officers questioned the wisdom of retiring to Kut. Given its location, the town was certain to be surrounded and besieged by the Ottomans. This placed not just the Indian army but the civilian population of Kut in mortal danger. While the townspeople had surrendered to the British without a fight, their cooperation could not be relied on in a prolonged siege. Weighing the alternatives of expelling the civilians, with the ensuing humanitarian crisis of making 7,000 townspeople homeless, and forcing the residents to share the hardships of a siege, Townshend and his commanders decided that leaving the residents of Kut in their homes would be the lesser of two evils. Events were to prove them wrong.

Townshend accepted the inevitability of a siege, believing it would be of short duration. The survivors of Salman Pak, combined with the garrison at Kut, gave Townshend a force of 11,600 combatants and 3,350 non-combatants, with sixty days’ rations. He was confident that his troops could withstand a few weeks of siege until the promised reinforcements reached Mesopotamia in January to relieve his position and resume the conquest of Iraq.

The Turkish advance guard reached Kut on 5 December. Nurettin Pasha’s forces began to take up positions around the town. By 8 December, Kut was encircled. The Ottomans, after a year of losing ground to the Anglo-Indian army in Mesopotamia, had turned the tide of battle. With the Noble Banner of Ali flying over the Tigris, the Ottoman army sensed victory was within reach.

World History

World History