Celtic willingness to import forms and techniques as well as trade objects has given rise to the view that, particularly in the late Hallstatt and Early La Tene periods, much of Europe north of the Alps was on the periphery and at the mercy of the ‘core’ cultures of the Mediterranean world. As much as anything it is the art which belies this dependent role since it continued to evolve and spread long after political and economic events brought a halt to southern imports. Unlike classical art, that of the early Celtic world is not so much aniconic as non-narrative and small scale, often almost miniaturist. There is little or no continuity with the occasional representations of dancing, weaving or burial rites illustrated on some of the funerary pottery and sheet metalwork of the late Hallstatt period. Such rare depictions as, for example, a military procession of warriors on an early La Tene sword from one of the later graves associated with the salt-working site of Hallstatt Itself (Figure 20.6) (Dehn 1970) have sources in this case in the eastern Hallstatt area and the long-lasting local tradition around the headwaters of the Adriatic of decorating bronze vessels (situlae) with scenes of feasting and military prowess. Local artists clearly used only those foreign elements which suited their visual grammatical syntax (Castriota 1981).

Figure 20.6 Detail of engraving on a bronze and iron scabbard, with remains of coral studs, from Hallscatt Grave 994, showing rare human figures. W, j cm. 400-350 BC. (Photo:

J. V.S. Megaw.)

Side by side with a continuing concern for patterning runs a tendency for visual punning. In a manner reminiscent of the oral traditions of the Old Irish and Welsh myths, forms are not always what they seem. Reverse, for example, what at first glance appears to be a faithful copy of a fifth-century Etruscan silen head and it transmogrifies into a clean-shaven, perhaps female, face (Megaw 1969); what seems a comma-like motif on closer inspection turns out to be a stylized bird’s head (Figures 20.5; 20.7). Shape-shifting in which foreground and background become interchangeable can also be seen in the Intricate and mathematically precise compass-based ornamentation of the fifth - or fourth-century BC openwork harness mounts produced by a number of specialized crafts-centres in eastern France or on the incised backs of the first century BC/ad southern British bronze mirrors. Asymmetry is also a feature; even in those objects which at first sight appear balanced, there are slight differences which mean that the viewer is constantly discovering new details (Figure 20.8). The use of lost-wax casting, where the clay mould has to be broken to extract the finished object and thus cannot be reused, also contributed to this lack of uniformity by making each object unique.

We have stated our view that Celtic art is the visible expression of a system of ideas, where even the most seemingly non-representational motifs may have a precise, perhaps religious, meaning. The very absence of the complete human form or of narrative art may indicate a taboo like that of Jewish or Moslem art on the making of certain types of representation. Working with Aboriginal artists in central desert

N %

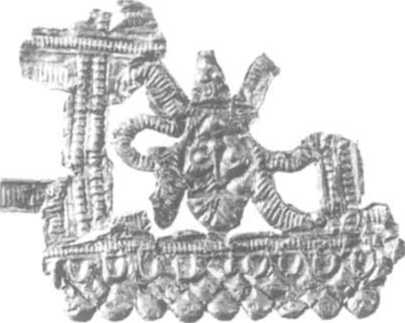

Figure jo,7 Openwork sheet-gold fragments with reversible faces from Bad DQrkheim, Kr. Ncustadt, Germany, Max. ht of heads 1.7 cm. Later fifth to early fourth century Bc. (Photo: Historisches Museum der Pfalz, Speyer.)

Regions of Australia has made it clear to us that paintings which look ‘decorative' or ‘abstract’ may contain very specific Dreamtime narratives and refer to precise geographic features, as well as serving as assertions of ownership. Recent work on ritual sites of the pre-Roman Iron Age has, however, shown how rarely such sites include objects of artistic note. Among major exceptions is the Celto-Ligurian region of the south of France where the influence of the classical world, particularly from the Greek colonies of the region such as Massalia, permeates everything from settlement plans to stone-carving (Duval and Heude 1983: 118-46). Yet much of the surviving wooden carving is in the form of votive offerings thrown into healing springs or wells in France and Germany in the early Roman period (Figure 20.12) (Planck et al. 1982; Deyts 1983; Romeuf 1986). Importantly, the ditched enclosures of northern France such as Gournay-sur-Aronde, with its evidence for sacrifice of horses and cattle along with the ritually destroyed weapons of those killed in battle, or the human ossuary at Ribemont, also include fine ornaments and other distinctive pieces (Brunaux et al. [985; Rapin and Brunaux 1988; Brunaux 1988). The decoration found on swords may have had specific, perhaps apotropaic, meaning for warriors.

World History

World History