The Hidden Island

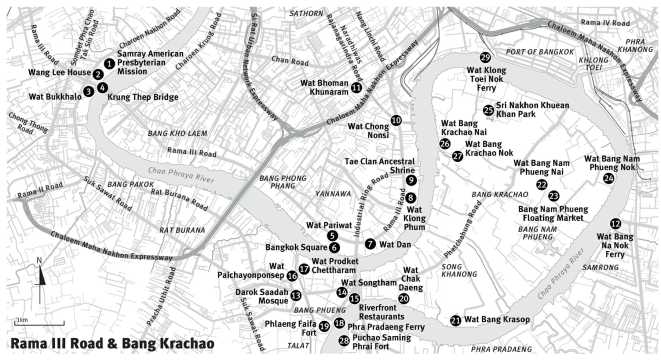

There are two sections to this walk and it is necessary to take a taxi from Rama lII Road to Phra Pradaeng and on to Bang Krachao, where it is also advisable to travel by car or by bicycle in order to cover the entire island.

Duration: 1 day

Looping around Bangkok is an inner ring road made up of sections of urban road that were already in existence and which over the course of several years were upgraded to arterial road status. The stretch that runs alongside the river from the Rama III Bridge to the port district of Klong Toei, where it changes its name and heads out through the northern suburbs, is Rama III Road.

Despite its riverside route, there is little that is scenic about Rama III Road. It had earlier become a semi-industrialised zone, with industries such as cement and sheet metal spreading down from the port and taking up large plots of land on the bank of the river. In the late 1980s, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration decided to designate this as a second business district, and cut a road directly through to Sathorn and Silom roads, alongside the old Chong Nonsi canal. Bangkok Bank established part of its head office here, the Krung Sri Bank set up its head office, the SV City mixed-use complex was built, and Montien opened their five-star Riverside Hotel. The Asian financial crash of 1997 put paid to most of the other grand schemes, scarring the district for years with half-built projects. Recent years have seen some life emerging in this area, greatly encouraged by the feeder bus that serves the Skytrain station at Sathorn Road, but dreams of a thriving riverside business district still seem rather remote.

Although the riverfront is hogged in most places by industry and commercial developments, rendering the river itself invisible, there are a series of beautiful riverside temples that continue on in their timeless way. To begin an exploration of these, it is necessary to start on the other side of the river, at the foot of the Rama iii Bridge, not at a Buddhist temple but at one of the first footholds of Christianity in Bangkok, where the Americans founded the Presbyterian Mission in 1849.

The Catholics have always been in Bangkok, before even the city was founded, represented principally by the descendants of the Portuguese of Ayutthaya, who over time had been absorbed into Siamese society and regarded as just another community with different religious beliefs, alongside the Cham Muslims, the Indian Hindus, the Chinese Taoists and others. The Protestants, however, didn’t arrive in Bangkok until 1828, when the London Missionary Society sent the Reverend Jacob Tomlin and the Reverend Carl Gutzlaff. More missionaries arrived in 1833, these being sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Intending to direct their efforts towards the Chinese population, they settled in a house near to Wat Samphanthawong in Chinatown. This is the group that Dr Dan Beach Bradley joined when he arrived in 1835, and in that year the mission moved across the water to the Kudi Cheen community. Missionaries from the American Presbyterian Mission began arriving in 1840 and stayed initially with the other Protestants in Kudi Cheen, where the influence of the community was growing, due in no small part to Bradley’s energetic work as a medical doctor, teacher and importer of Siam’s first printing press.

The Presbyterians founded their own church, initially holding services and meetings in their living quarters, and by 1857 they were able to buy a plot of land at Samray, a village on the Thonburi side that took its name from the samray trees that grew there on the riverfront. Here they decided to build a church, and although it took five years to raise the funds and construct the building, Samray Church opened in 1862. Although Samray may have seemed an odd destination, this part of the riverbank was quickly being transformed from a wilderness into an industrial area, and the population was growing. There was also the large population of Westerners directly across the river, at the lower end of Charoen Krung Road. Samray became the centre of the Presbyterian community, and along with the church there was a boys’ school, a printing press, and housing for the missionaries and the local people who became involved with running the community. The school was later to move across the river, where it became the Bangkok Christian College.

Samray Church is reached via the quiet lane of Charoen Nakhorn Soi 59, a thoroughfare that is little more than a footpath, and the church sits directly on the riverbank, fronted by a green lawn. A small jetty is there for anyone travelling by boat. The original church fell into disrepair half a century after it was built, and this present structure was erected in 1910, taking the same design. A belfry was added as a separate structure in 1912. The lines of the church are clean and simple, with three arches on the plain flat frontage, which is adorned only by a cloverleaf pattern and the year of construction. In recent years the church has been painted a dark yellow, which no doubt had some of the more conservative members of the congregation shaking their heads, but, contrasting with the red-tiled roof, the effect is rather pleasing. The river originally came almost to the church steps, but reclamation during the latter half of the twentieth century has added enough land for a congregation to gather. A church office and community hall was added in 1963. Some of the church land was sold off to members of the congregation in 1916, and as a result the lane has several very pleasant old wooden houses dating from this time. The cemetery is at the entrance to the lane, separated from Charoen Nakhorn by a high wall, and is immaculately kept.

Immediately next to Samray Church are the remains of one of those industries that brought so many people into the locality during the second half of the nineteenth century. The origins of the Wang Lee family business have been described earlier on in the section on the old Thonburi harbour. There were five rice mills owned by the family, three of them being located here. One was on the site of the present Anantara Hotel: it burned down in 1976. Another was on land that has recently been cleared, except for the magnificent teak house built for the owners, which although dilapidated still stands on the riverfront next to the church and is apparently due to be restored. The third can be found on the other side of the Krung Thep Bridge, renovated and converted into a restaurant. The mill came under the name of Long Heng Lee, and an original signboard hangs proudly inside the restaurant. On this site, too, is a house built for the owners, which has been restored and acts still as a residence. The mill dates from the 1880s or 90s, the timber construction being very typical of the time. Wang Lee was not the only operator of rice mills in this area: by 1903 there were eleven mills in this immediate area, out of a total of almost

Fifty in Bangkok.

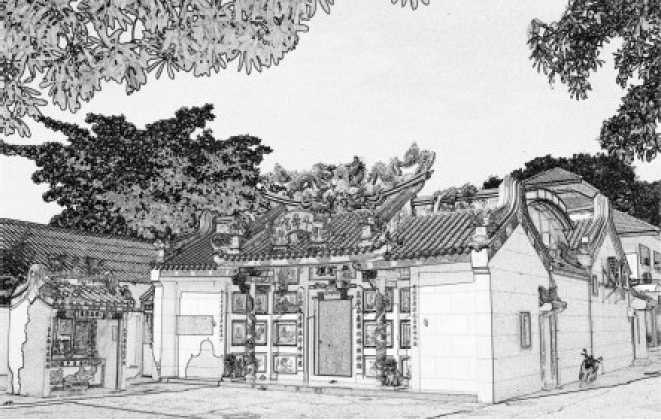

One of a pair of ancient Chinese shrines flanking the Krung Thep Bridge.

On the far side of the restaurant is a temple that, to the best of my knowledge, is the only one in Thailand that is set on top of a three-storey building. Wat Bukkhalo was founded in 1767, and while the original ubosot is still here on the riverbank, a chapel and a number of salas have been built on the roof of the community centre; the temple is a striking sight for anyone passing across the Krung Thep Bridge or the Rama iii Bridge in a southerly direction, particularly early in the morning when the sun catches the red and gold structures perched on top of their white platform.

It was probably the Chinese millers or sailors who built the two Chinese shrines on either side of the Krung Thep Bridge, and they predate the bridge itself Again, for anyone passing over the bridge, in either direction, they present an intriguing flourish of red and white gables and rampant dragons, but as with most Chinese shrines there is no known history: they are simply modest places of worship. The

Krung Thep Bridge was opened in the middle of 1959, and at the time was only the second road bridge across the river. Although lacking the splendour of the Memorial Bridge, it is still a fine example of steel truss design, and it too has a bascule span for allowing the passage of large ships. Unlike the older structure upriver, the bridge can still open. Fuji Car Manufacturing Co Ltd built the bridge, which has a total length of 626.25 metres (2,053 ft). The neighbouring Rama iii Bridge was opened in 1999 and was built as part of the inner ring road, taking the strain of the older structure.

Rama III Road does not readily give up its temple treasures, certainly not to the casual passer-by. Wat Chan Nok is directly on the riverbank, a small and pretty temple that is reached only by entering Soi 6 and proceeding to the end of the lane; unless viewed from the river, it is otherwise invisible. Wat Bang Khlo is similarly hidden, reached by travelling along Soi 20, or admired from the Montien Riverside Hotel next door. Wat Pariwat is the first visible temple, occupying a huge area of land between the river and the road, next to the clothes shops and restaurants of Bangkok Square, and visible from some distance because of the striking deep-blue colouring of the ubosot roof tiles. Much of this temple structure is very modern, and contemporary images are to be found in the compound, including Captain Hook and his pirate companions helping to hold up the eaves on one of the roof structures, and the footballer David Beckham, who appears as a golden embossed image on the base of the principal Buddha figure. Although only 30 centimetres (11.8 in) high, and standing at the end of a frieze of garudas supporting the altar, this image has become so well-known amongst locals that the temple is increasingly known as David Beckham Temple. Placed there in 1998, with the enthusiastic permission of the abbot, the figure is wearing a football shirt bearing the name of team sponsor Sharp. The Thais are football crazy, and Beckham’s name is revered, so perhaps it is not surprising to see him turn up as a deity in a Bangkok temple. “Same-same but different”, as the Thais might say.

Wat Dan, nearby, is another substantial temple and serves as a particularly extensive monastery, its cluster of accommodation around the thoroughfare that passes through the compound being home to a large community of novice monks, many of them pre-teen youngsters who spend time there during the annual Rains Retreat, and who appear to be easily diverted when a foreigner walks past their windows, peering out with friendly if distinctly un-monk like grins.

Continuing along this side of the road, there is a modest temple archway across a narrow lane, and walking down here will lead us past a school and into the compound of Wat Klong Phum, built beside a tiny canal and enjoying a pastoral setting on the bank of the river. The school is part of the temple, and within one of its buildings the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration maintains a small district museum. A wrought-iron fence further along Rama iii Road reveals what at first appears to be a small Chinese temple with a low roof and blue ceramic tiling on the wall, but which is actually the frontage of the Tae Clan Ancestral Shrine, and behind this is a large and beautifully proportioned courtyard with a river frontage.

Further up Rama iii Road the Chong Nonsi canal runs beneath the road to empty into the river, where there is a sluice gate and pumping station. On the corner where Naratiwat Road was cut to link Rama iii with Sathorn and Silom stands Wat Chong Nonsi, one of Bangkok’s oldest temples, dating from at least the latter half of the seventeenth century. The grounds of the temple contain more than thirty chedis, and there is an ornate bell tower with a balcony Although the wiharn is relatively new the ubosot is original, displaying the characteristic boat shape of its time, and rather austere, being painted white and with its roof aged into a light brown colour. Measuring only 20 metres (65.5 ft) long by 10 metres (32.8 ft) wide, this building could be overlooked as being simply an interesting survival in an urban landscape, except that on its inner walls are some of Bangkok’s most remarkable murals, painted between 1657 and 1707, and famous for depicting the everyday and sometimes bawdy lives of ordinary people within its scenes from the Jataka. This is the earliest surviving temple mural in Bangkok, and the only Ayutthaya-era temple in which both the murals and the architecture are of the same period, with no renovations. Because of its historical purity and value the ubosot is usually kept locked and viewed only on request.

Behind Wat Chong Nonsi, its canal-side setting lost when the road was laid, is a Mahayana Buddhist temple that is regarded as being one of the finest examples of Chinese temple architecture in Thailand. Wat Bhoman Khunaram is a fairly recent structure, built in 1959 by a Chinese spiritual master who later became the temple’s first abbot. The buildings and artworks in this five-acre compound are a mixture of Thai, Chinese and Tibetan styles, and the enormous black and gold alms bowl that towers over the roof is a familiar local landmark. King Bhumibol in 1970 came to perform the raising of a tiered umbrella above the main building, and to commemorate the visit his initials have been placed above the temple entrance. Wat Bhoman is the centre of the Chinese Order of Buddhist Monks in Thailand.

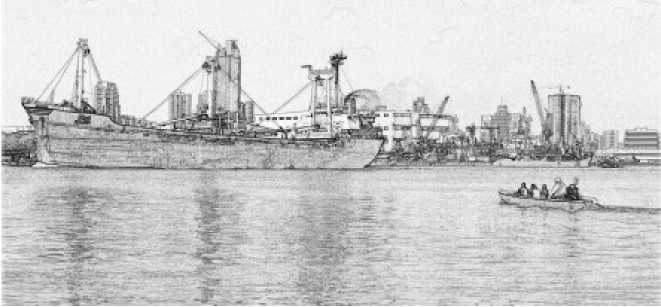

Rama iii Road, for most of its length, is double-decked. As the confined surroundings made it impossible for the highway engineers to add slip-road ramps, the elevated section subsides to ground level for major junctions. Viewed from sideways on, the road would look like a massive switchback. Taxi drivers appreciate this. The way is usually uncongested and the driver can really put on a turn of speed, sailing along the elevated sections, lurching down the ramps that are corrugated with expansion and drainage joints, and landing with a satislyingly springy bounce on the flat pad of the ground deck before flooring the pedal for the up ramp. For the taxi driver who spends most of his day in a semi-mobile carpark, it must be exhilarating. For the passenger who, to take a random example, has just drunk a large cappuccino at his local Starbucks, it can, however, be alarming. At such a time the passenger may turn his eyes to the horizon, like a seasick sailor, and if he looks towards the river he will see a remarkable sight: a long wall of almost unbroken green jungle. This only begins at the upper end of Rama iii, roughly from the SV City complex, and with almost no riverside temples from here on, as the river flows into the industrialised port district at Klong Toei, there are few ground-level vantage points. Perhaps the best place to view the river is from the mouth of the Chong Nonsi canal, where the curious observer will be rewarded with a Conradesque view of coastal freighters chugging past against a jungle backdrop, heading to and from one of the small jetties, or further up to the shipyard at the Krung Thep Bridge; and he may wonder just where the city has gone.

A map will soon provide the answer. The river here describes an enormous loop that doubles back upon itself and almost touches at the district named Phra Pradaeng. The effect is to create what is effectively an island in the middle of the city. A small canal, Klong Lat Pho, was cut in 1628 to allow light craft to bypass the loop, but the angle of the cutting was such that the river flow could not inundate it, as happened further upstream at Thonburi. Klong Toei, which occupies most of the loop on the Bangkok side, had long been a port town, going back centuries to when the ocean came a lot further inland, and so this part of the river was important to shipping. The cutting of the Hua Lampong canal during the time of Rama IV gave the port even more importance, connecting it both with the city centre and the waterway that led through to the rich rice-growing province of Chachoengsao. It is from the lower end of this canal that Klong Toei takes its name: the southern end of the canal became known for the pandan plants, toei, that grew along the waterside. Klong Toei was developed as a modern port starting from 1938, but its limited capacity for heavy shipping and the traffic chaos caused by trailer trucks on land resulted in the founding of Laem Chabang deep-sea port in Chonburi province early in the 1980s. Amongst all this volume of trade and encroachment of human habitation on both the Bangkok and the Samut Prakan sides of the river, the land within the loop has remained almost totally undeveloped. Referred to either as the Phra Pradaeng peninsula, or more often Bang Krachao (although the Thais refer to it as Krapow Moo, which means “pig’s stomach”), this is a huge area of green countryside in which quiet villages snooze down peaceful lanes, where many people travel by bicycle, and where small temples are buried away amongst the greenery. The visitor could easily imagine that he is upcountry was it not for the occasional startling sight of a familiar Bangkok tower poking up from beyond the trees.

Gateway to Phlaeng Faifa, one of the forts built to protect the Chao Phraya estuary.

A few years ago, two magnificent new bridges opened across the Chao Phraya at the neck of the peninsula, taking the highway across the water next to SV City, with a necessarily tightly woven cloverleaf junction between the two. At the same time the Lat Pho shortcut canal, which had measured no more than 15 metres (49 ft) wide and 2 metres (6.5 ft) deep, and which ran for just 600 metres (656 yds) across the narrowest part of the isthmus, was widened to 65 metres (213 ft) as part of a flood alleviation scheme. The bridges have rendered Bang Krachao more easily accessible, although as there is no reason for anyone to go there, the peninsula remains as quiet as it was before the bridges—which are called Bhumibol I and Bhumibol ii, and which complete the inner and outer ring roads—were built. (The bridges are cable-stayed spans with gigantic A-frames at either end. The frames are an abstract rendering of the traditional Thai form of greeting, the wai, a charming notion for anyone entering the city via the river, although sadly these days this is generally confined to the crews of container ships.) There are three ferry crossings: those from Wat Klong Toei Nok and Wat Bang Na Nok are for foot passengers and cyclists, with landings directly on the island, and the third being a car ferry whose captain sits in a tiny cabin atop a square tower at the stern, and which plies from Puchao Saming Phrai Road in Samut Prakan to Phra Pradaeng. Near to Phra Pradaeng ferry pier and perched on the river’s edge is a row of restaurants known only to local Thais, and which afford memorable views of giant container ships travelling to and from Klong Toei.

Phra Pradaeng sits on the west side of the thin strip of land where the Chao Phraya almost meets itself, and is a crowded little town that seems to be not quite of Greater Bangkok, a feeling enhanced by the cycle-rickshaws that still ply the streets. But there is more than this: the temples are different, some of the older people dress in a different way, and sometimes even the festivals are a little different, Songkran for example being held a week later than in central Bangkok. This is Mon territory, settled after the fall of Ayutthaya, when it became prominent in helping to guard the entrance to the Chao Phraya. Rama I ordered a fort to be built here in 1809, and in 1815 Rama II commanded another eight forts to be built. The Mon immigrants having proved such fierce enemies of the Burmese, several hundred Mon men and their families were settled along the river to man the forts and to populate the town that the king was building here, Nakorn

Keunkan. The community has grown from that original migration. Phlaeng Faifa, the only remaining fort, is to be found near the ferry pier, although there is little left except for a solid archway and the earthworks topped with stone ramparts and ancient cannon. The site is now a small public park. Most of the other forts have been completely lost and forgotten, their stones long ago taken away for other building works, but the ruins of one, Puchao Saming Phrai, can be found on the Samut Prakan side of the river, almost directly opposite, completely neglected except for a row of rusting cannon along the riverbank.

So thoroughly did the Mon settle Phra Pradaeng that there is only one Thai Buddhist temple amongst the thirty-eight temples within the administrative district of Amphoe Phra Pradaeng: all the others are of the Mon Buddhist sect. Wat Prodket Chettharam was built in the time of Rama ii and stands on the bank of the Lat Ruang canal, which was cut at that time by Mon immigrants under the direction of the king; the depth of the Lat Pho canal was reduced because of the saline water that was travelling upstream and seeping into the irrigation system that fed the orchards established there. Klong Lat Ruang passes in a diagonal fashion across Phra Pradaeng to avoid inundation by the river, and was too narrow for larger shipping. In 1907 the Maenam Motorboat Company, a subsidiary of Siam Electricity, which owned Bangkok’s electric trams system, set up a steam tram that ran parallel to the Lat Ruang canal because the waterway was not large enough to handle their boats. The trams were later converted to petrol but the system was abandoned in 1940 because of wartime fuel shortages. Wat Prodket’s position next to this quiet and clean waterway has enabled the creation of a small moat around the central chedi, an attractive area set with stone benches. Although designed for devotees of the Thai style of Buddhism, Wat Prodket shows strong elements of Mon design in its architecture. The roofs of the ubosot and wiharn are both covered with Mon ceramic shingles and there are no rooftop decorations, giving a slightly cropped look to the outline, while the gables are flat and with a vine pattern made from ceramic fragments placed on stucco. A Chinese gate leads over the moat, and there are Chinese pavilions. The temple has both a sitting Buddha, in the Subduing Mara position, and a Reclining Buddha. Inside the wiharn are Dharma illustrations performed in Western art style, which is extremely rare, and inside the mondop is a representation of the Buddha’s footprint, inlaid with pearl.

Facing Wat Prodket on the other side of the Lat Ruang canal is Wat Paichayonponsep, distinctively Mon in design, its entrance arch painted in red ochre and its flat eaves embossed with ceramic patterns. A leafy pathway leads alongside the canal, and with a large screen of trees and a small waterside village, this spot has a rural atmosphere.

Following the canal road from Wat Prodket leads through a Muslim community, with the green domes and tall minaret of Darok Saadah Mosque towering over the houses, and picking up the main road here will take us over the canal to Songtham Road, and to one of the most prominent local landmarks, Wat Songtham, set near the ferry pier and resplendent behind a magnificent red-and-gold fence. The enormous Mon-style chedi dominates the southern corner of the compound, its gleaming white base formed into three tiers, with rows of golden Buddha images encircling the chedi on each tier. The red-and-gold theme is carried through to the bells that hang outside the ubosot, and each of the monk images placed in a line in a nearby sala is heavily encrusted in gold leaf. Wat Songtham dates from the time of Rama III, and is a royal temple, second class. Alongside the temple runs Phetchahung Road, and following this leads over the Lat Pho canal and across the entire length of the Phra Pradaeng peninsula.

The scenery begins to change immediately: the narrow streets have gone, to be replaced by green countryside and small villages, and an unhurried way of life. Away from the two-lane road there are orchards, jungle, mangrove swamps, and hidden temples. This is still

Mon country, settled at the same time as Phra Pradaeng and in the years after, the Mon language can still be heard and Mon script seen on older buildings. Turning under the archway for Wat Chak Daeng will lead us along a narrow country lane to an old wall decorated with green Dharma wheels and into the temple compound, which enjoys a garden setting on the bank of the river. A traditional stupa has been built here next to the water, a mound-like construction made from red clay bricks, reminding us that the Mon were outstanding makers of unglazed clay pottery. Next to the stupa is a golden chedi atop the cream-coloured wiharn, surrounded by small golden Buddha images: the chedi is floodlit at night, a striking sight from the far side of the river at Phra Pradaeng. A small notice next to the temple relates that it was built by a Mon community who had fled from Ayutthaya and settled here during the Thonburi era.

Small private ferry service plying between Rama HI Road and Bang Krachao.

Follow Phetchahung Road a little further, and there is a turning for Wat Bang Nam Phueng. This lane leads through fields and woodland, across a bridge that spans a narrow waterway, and here we are at one of the peninsula’s few conscious attempts at a tourist attraction: a floating market. A number of vendor boats line the canal side, covered by netting to reduce the sun’s rays, and visitors walk along concrete walkways to the stalls and the food outlets, so this is not really a floating market at all: although, admittedly, “concrete walk-way market” doesn’t quite have the same cachet. Bang Nam Phueng Floating Market is a recent innovation by the villagers themselves and designed primarily for Thais, and consequently is a lot less pushy than other floating markets that cater to foreign visitors. There are some quality handicrafts and food products from the otop project available, some reasonably priced clothing, and of course, good food. The market is open only at the weekends but is well worth a visit. An added attraction are the sampan rides that are available along the canal, which unlike most of Bangkok’s klongs is clean and fragrant. Along the lane that runs past the market is one of the community’s two temples, Wat Bang Nam Phueng Nai, a small temple that has a tiered stupa topped with a golden image, and beyond this are green fields and orchards.

Taking the lane that leads to the ferry pier for Bang Na brings us to the second temple, Wat Bang Nam Phueng Nok (nai and nok mean, respectively, “inner” and “outer”), which is far larger than its sibling and sits on the river’s edge. A large golden Buddha is seated facing the ferry pier, and a fat Buddha is placed in the cemetery, its tummy button used for offerings. Behind the temple buildings on the pierside are the original chapel and ordination hall, dating back to the early days of the Mon settlement, but long neglected and crumbling away. They are hidden now behind overgrown trees, with small homesteads up against the walls, their exterior decor gone, their interiors bare, the remains of ancient murals still to be seen on the walls. The Buddha images are still here and are regularly visited.

At least two other temples on the peninsula have allowed their former buildings to fall into disuse, although not to the extent of Wat Bang Nam Phueng Nok. Wat Pa Kedi has a disused chapel crammed in behind a newer structure, and although stripped of its grandeur is sound enough. The small original chapel at Wat Bang Krasop, although mainly plain brick and stucco on the outside, is in a good state of repair and has beautiful mouldings over its windows and the doorway arch. What appears to be a new chapel in the compound was having its interior images painted during a recent visit, enormous swirling designs of purple and gold, and was the work of just one artist, working alone on a scaffold.

Phetchahung Road ends at the ferry pier looking out across at the yellow gantry cranes of Klong Toei, and Bang Krachao will almost certainly remain as unspoiled jungle island. The late 1970s had seen protection orders placed on the peninsula, the original intention having been for controlled leisure development. The developments never happened, and the Thais have become conservation minded in more recent times. About a tenth of the total area of almost a thousand acres is protected, acquired and maintained as Sri Nakhon Khuean Khan Park by the Royal Forest Department. With its nature trails, cycle paths and large lake where boats can be hired, the park attracts a modest number of local tourists. There is a refinery near to the bridge, and some warehousing, but otherwise there is no industry. Recent years have seen some residents offering homestay accommodation, there are companies that operate cycling tours, there is a place displaying Siamese fighting fish, and a handful of residents who have been peacefully making incense sticks for several generations have now, to their bemusement, become a tourist attraction. Life is quiet here. There is no police station. You will look hard to find an ATM. The restaurants are all very local, most of them roadside stalls. The modern city is only a ferryboat ride away, but there is no hurry to travel back across the water.

World History

World History