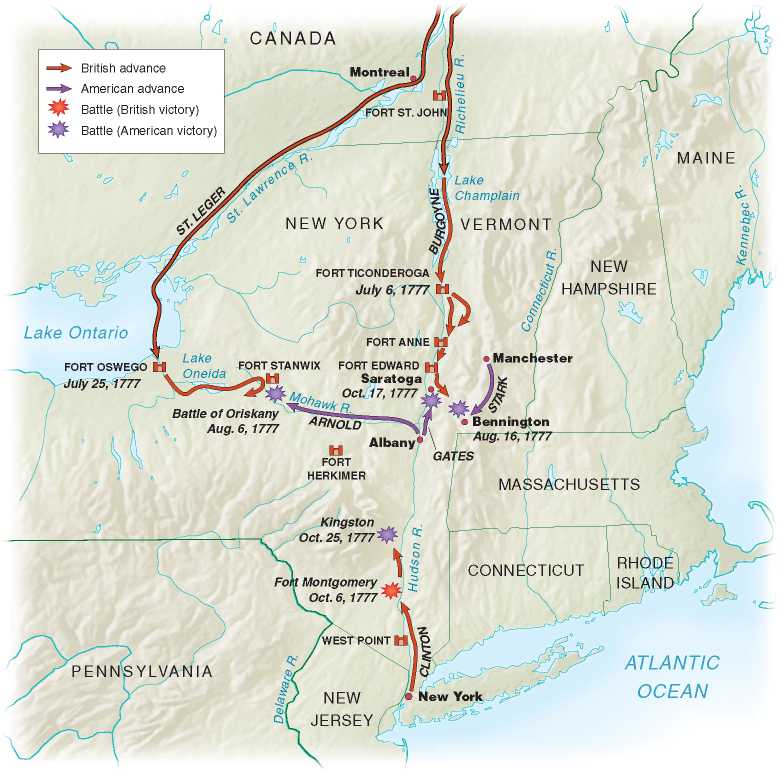

When spring reached New Jersey in April 1777, Washington had fewer than 5,000 men under arms. Great plans—far too many and too complicated, as it turned out—were afoot in the British camp. The strategy called for General John Burgoyne to lead a large army from Canada down Lake Champlain toward Albany while a smaller force under Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger pushed eastward toward Albany from Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario. General Howe was to lead a third force north up the Hudson. The Patriots would be trapped and the New England states isolated from the rest.

As a venture in coordinated military tactics, the British campaign of 1777 was a fiasco. General Howe had spent the winter in New York wining and dining his officers and prominent local Loyalists and having a torrid affair with the wife of the officer in charge of prisoners of war. He was less attentive to his responsibilities for the British army advancing south from Canada.

General “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne, a charming if somewhat bombastic character (part politician, part poet, part gambler, part ladies’ man), yet also a brave soldier, had begun his march from Canada in mid-June. By early July his army, which consisted of 500 Indians, 650 Loyalists, and

6,000 regulars, had captured Fort Ticonderoga at the southern end of Lake Champlain. He quickly pushed beyond Lake George but then bogged down. Burdened by a huge baggage train that included 138 pieces of generally useless artillery, more than thirty carts laden with his personal wardrobe and supply of champagne, and his mistress, he could advance at but a snail’s pace through the dense woods north of Saratoga.6 Patriot militia impeded his way by felling trees across the forest trails.

St. Leger was also slow in carrying out his part of the grand design. He did not leave Fort Oswego until

During the American Revolution Fort Niagara was nearly indefensible; later, its walls were expanded and strengthened.

July 26, and when he stopped to besiege a Patriot force at Fort Stanwix, General Benedict Arnold had time to march west with 1,000 men from the army resisting Burgoyne and drive him back to Oswego.

Meanwhile, with magnificent disregard for the agreed-on plan, Howe wasted time trying to trap Washington into exposing his army in New Jersey. This enabled Washington to send some of his best troops to buttress the militia units opposing Burgoyne. Then, just when St. Leger was setting out for Albany, Howe took the bulk of his army off by sea to attack Philadelphia, leaving only a small force commanded by General Sir Henry Clinton to aid Burgoyne.

When Washington moved south to oppose Howe, the British commander taught him a series of lessons in tactics, defeating him at the Battle of Brandywine, then feinting him out of position and moving unopposed into Philadelphia. But by that time it was late September, and disaster was about to befall General Burgoyne.

The American forces under Philip Schuyler and later under Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold had erected formidable defenses immediately south of Saratoga. Burgoyne struck at this position twice and was thrown back both times with heavy losses. Each day more local militia swelled the American forces. Soon Burgoyne was under siege, his troops pinned down by withering fire from every direction, unable even to bury their dead. The only hope was General Clinton, who had finally started up the Hudson from New York. Clinton got as far as Kingston, about 80 miles below Saratoga, but on October 16 he decided to return to New York for reinforcements. The next day, at Saratoga, Burgoyne surrendered. Some 5,700 British prisoners were marched off to Virginia.

This overwhelming triumph changed the course and character of the war. France would probably have entered the war in any case; the country had never reconciled itself to its losses in the Seven Years’ War and for years had been building a navy capable of taking on the British. Helping the Americans was simply another way of weakening their British enemy. As early as May 1776 the Comte de Vergennes, France’s foreign minister, had persuaded Louis XVI to authorize the expenditure of 1 million livres for munitions for America, and more was added the next year. Spain also contributed, not out of sympathy for the Revolution, but because of its desire to injure Great Britain. Soon vital supplies were being funneled secretly to the rebels through a dummy company, Roderigue Hortalez et Cie. When news of the victory at Saratoga reached Paris, the time seemed ripe and Louis XVI recognized the United States. Then Vergennes and three American commissioners in Paris (Benjamin Franklin, Arthur Lee, and Silas Deane) drafted a commercial treaty and a formal treaty of alliance. The two nations agreed to make “common cause and aid each other mutually” should war “break out” between France and Great Britain. Meanwhile, France guaranteed “the sovereignty and independence absolute and unlimited” of the United States. The help of Spain and France, Washington declared, “will not fail of establishing the Independence of America in a short time.”

When the news of Saratoga reached England, Lord North realized that a Franco-American alliance was almost inevitable. To forestall it, he was ready to give in on all the issues that had agitated the colonies before 1775. Both the Coercive Acts and the Tea Act would be repealed; Parliament would pledge never to tax the colonies.

Instead of implementing this proposal promptly, Parliament delayed until March 1778. Royal peace commissioners did not reach Philadelphia until June, a month after Congress had ratified the French treaty. The British proposals were icily rejected, and while the peace commissioners were still in Philadelphia, war broke out between France and Great Britain.

The American Revolution, however, had yet to be won. After the loss of Philadelphia, Washington had settled his army for the winter at Valley Forge, 20 miles to the northwest. The army’s supply system collapsed. Often the men had nothing to eat but “fire cake,” a mixture of ground grain and water molded on a stick or in a pan and baked in a campfire. According to the Marquis de Lafayette, one of

Saratoga Campaign, September 19 to October 17, 1777 In Mil the British, who controlled New York City, decided to drive the Patriots from the rest of the colony through a three-pronged attack on Albany. All three British generals failed to achieve their objectives: St. Leger, coming from the west, failed to advance beyond Ft. Stanwix; Burgoyne, from the north, bogged down and found himself surrounded; and Clinton, from New York City, made it to Kingston, but failed to relieve Burgoyne, whose army surrendered.

Many Europeans who volunteered to fight on the American side, “the unfortunate soldiers. . . had neither coats, nor hats, nor shirts, nor shoes; their feet and legs froze till they grew black, and it was often necessary to amputate them.”

To make matters worse, there was grumbling in Congress over Washington’s failure to win victories and talk of replacing him as commander-in-chief with Horatio Gates, the “hero” of Saratoga. (In fact, Gates was an indifferent soldier, lacking in decisiveness and unable to instill confidence in his subordinates.)

As the winter dragged on, the Continental army melted away. So many officers resigned that Washington was heard to say that he was afraid of “being left Alone with the Soldiers only.” Since enlisted men could not legally resign, they deserted by the hundreds. Yet the army survived. Gradually the soldiers who remained became a tough, professional fighting force.

World History

World History

![Black Thursday [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432470149_1431513568_003514b1_medium.jpeg)