Late one night in 1995, after serious drinking, Danish directors Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg took twenty-five minutes to jot down a manifesto calling for a new purity in filmmaking. The new waves of the 1960s had betrayed their revolutionary calling, and now new technology was going to democratize cinema. "For the first time, anyone can make cinema. "4 But some discipline was necessary, so von Trier and Vinterberg laid down an "indisputable set of rules" for the new avant-garde: a "Vow of Chastity."

The vow required that the film be shot on location (using only props naturally found there). The camera had to be hand-held and the sound recorded directly, so music could arise only from within the scene itself. The film had to be shot in the 1.33:1 format, in color, and without filters or laboratory reworking. It could not be set in another period of history nor be a genre film (apparently ruling out police and action pictures, science fiction, and other Hollywood genres). The film could not include "superficial action": "Murders, weapons, etc. must not occur." The director must not be credited. Above all, a director had to pledge that the film would be not an artwork but "a way of forcing the truth out of my characters and settings." Soon thereafter two other Danish filmmakers signed on. The four created the Dogme 95 collective.

Distributed in a Paris symposium devoted to cinema's hundredth anniversary, the manifesto attracted little notice until 1998. That year the film labeled Dogme #1, Vinter-berg's The Celebration, won the Jury Prize at Cannes, and Dogme #2, von Trier's The Idiots, won a critics' award at the London Film Festival. Mifune (1999), by S0ren Kragh-Jacobsen, was Dogme #3. After winning a major prize in Berlin, it went on to gross $2 million internationally. Dogme began issuing certificates for projects that adhered to the Vow of Chastity, while directors who strayed from it (as most did) made public confession on the Dogme website.

Since the Dogme films were closely tied to von Trier's Zentropa company, many critics dismissed Dogme 95 as a publicity stunt. If it was, it succeeded spectacularly. Danish cinema became a center of critical attention. On New Year's Eve 2000, each Dogme director shot a live film and broadcast it on a different television channel. Viewers were encouraged to switch among the films and create their own Dogme 95 movie. One-third of Denmark tuned in.

The Dogme brethren insisted that they were serious. They held that film's increasingly complex technology and bureaucracy hampered genuine creation. One could, however, fight Hollywood's globalization by going back to basics; Kragh-Jakobsen compared the group to rockers rediscovering "unplugged" music. Like John Cassavetes and the Direct Cinema filmmakers, they sought to capture the

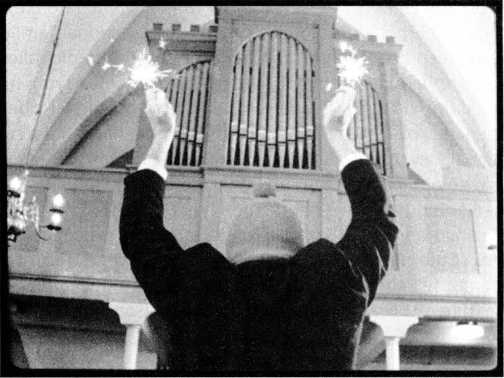

28.3 Liberation from city conventions in Mifune.

Unrepeatable here and now. The vow declared that the director must "regard the instant as more important than the whole."

Central to the movement was a collaboration between director and performers. In the typical Dogme film, the actors and directors worked out the scene, often without a script, and then shot it in catch-as-catch-can fashion. For The Celebration, the actors sometimes operated the camera, and all were present to witness each scene. Dogme directors favored digital video; Vinterberg noted that actors tended to forget the presence of small cameras. Dogme #4, Kristian Levring's The King Is Alive (2001), used three cameras so that none of the actors knew when she or he was being filmed.

Von Trier claimed that the formal rigidity of his earlier films dissatisfied him, and the vow provided a rationale for the freer-form shooting that emerged in Breaking the Waves. Vinterberg agreed: "I had the impression that my way of filming was imprisoned by conventions: returning to standard techniques to make people cry, use artificial light for a night scene. . . . There are things in cinema that you're supposed to do, and you do them without asking questions."5 All the Dogme directors stressed that filmmakers had to start reflecting on why they made certain choices; by working under a self-imposed simplicity they could relearn how to tell stories on film. Although the vow attacked the idea of the auteur, most directors found their Vow projects becoming highly personal.

World History

World History