Wilson was preeminently a teacher and preacher, a specialist in the transmission of ideas and ideals. He excelled at mobilizing public opinion and inspiring Americans to work for the better world he hoped would emerge from the war. In April 1917 he created the Committee on Public Information (CPI), headed by the journalist George Creel. Soon

75,000 speakers were deluging the country with propaganda prepared by hundreds of CPI writers. They pictured the war as a crusade for freedom and democracy, the Germans as a bestial people bent on world domination.

A large majority of the nation supported the war enthusiastically. But thousands of persons—German Americans and Irish Americans, for example; people of pacifist leanings such as Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House; and some who thought both sides in the war were wrong—still opposed American involvement. Creel’s committee and a number of unofficial “patriotic” groups allowed their enthusiasm for the conversion of the hesitant to become suppression of dissent. People who refused to buy war bonds were often exposed to public ridicule and even assault. Those with German names were persecuted without regard for their views; some school boards outlawed the teaching of the German language; sauerkraut was renamed “liberty cabbage.” Opponents of the war were subjected to coarse abuse. A cartoonist pictured Senator Robert La Follette, who had opposed entering the war, receiving an Iron Cross from the German militarists, and the faculty of his own University of Wisconsin voted to censure him.

Although Wilson spoke in defense of free speech, his actions opposed it. He signed the Espionage Act of 1917, which imposed fines of up to $10,000 and jail sentences ranging to twenty years on persons convicted of aiding the enemy or obstructing recruiting, and he authorized the postmaster general to ban

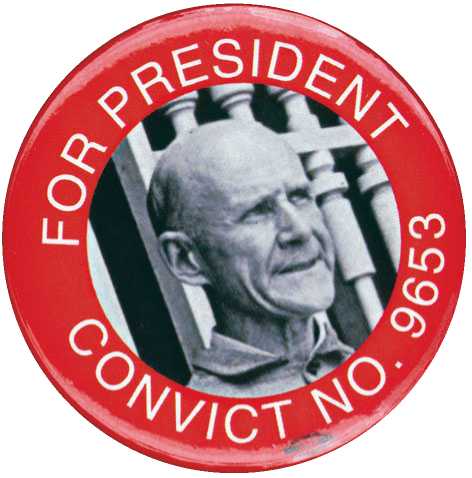

Eugene V. Debs ("Convict #9653") was imprisoned for speaking against the war. In 1920 he ran as the Socialist candidate for president from the Atlanta federal prison, receiving nearly a million votes.

From the mails any material that seemed treasonable or seditious.

In May 1918, again with Wilson’s approval, Congress passed the Sedition Act, which made “saying anything” to discourage the purchase of war bonds a crime, with the proviso that investment counselors could still offer “bona fide and not disloyal advice” to clients. The law also made it illegal to “utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the government, the Constitution, or the uniform of the army or navy. Socialist periodicals such as The Masses were suppressed, and Eugene V. Debs, formerly a candidate for president, was sentenced to ten years in prison for making an antiwar speech. Ricardo Flores Magon, an anarchist, was sentenced to twenty years in jail for publishing a statement criticizing Wilson’s Mexican policy, an issue that had nothing to do with the war.

These laws went far beyond what was necessary to protect the national interest. Citizens were jailed

Table 23.1 Suppression of Liberties during World War I

|

Federal Action |

Year |

Consequence |

|

Espionage Act |

1917 |

Prohibited words or actions that would aid the enemy or obstruct recruiting efforts |

|

Sedition Act |

1918 |

Prohibited people from "saying anything"that might discourage purchase of war bonds or otherwise undermine the federal government or the Constitution |

|

Schenck v. United States |

1919 |

Supreme Court upheld limitations on free speech during times of "clear and present danger" to the nation |

For suggesting that the draft law was unconstitutional and for criticizing private organizations like the Red Cross and the YMCA. One woman was sent to prison for writing, “I am for the people, and the government is for the profiteers.”

The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act in Schenck v. United States (1919), a case involving a man who had mailed circulars to draftees urging them to refuse to report for induction into the army. Free speech has its limits, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., explained. No one has the right to cry, “Fire!” in a crowded theater. When there is a “clear and present danger” that a particular statement would threaten the national interest, it can be repressed by law. In peacetime Schenck’s circulars would be permissible, but not in time of war.

The “clear and present danger” doctrine did not prevent judges and juries from interpreting the espionage and sedition acts broadly, and although in many instances higher courts overturned their decisions, this usually did not occur until after the war. The wartime repression far exceeded anything that happened in Great Britain and France. In 1916 the French novelist Henri Barbusse published Le Feu (Under Fire), a graphic account of the horrors and purposelessness of trench warfare. In one chapter Barbusse described a pilot flying over the trenches on a Sunday, observing French and German soldiers at Mass in the open fields, each worshiping the same God. Yet Le Feu circulated freely in France and even won the coveted Prix Goncourt.

•••-[Read the Document Buffington, Friendly Words to the Foreign Born at Www. myhistorylab. com

Attitude in supporting a federal child labor law: “We cannot afford, when we are losing boys in France, to lose children in the United States.”

Men and women of this sort worked for a dozen causes only remotely related to the war effort. The women’s suffrage movement was brought to fruition, as was the campaign against alcohol. Both the Eighteenth Amendment, outlawing alcoholic beverages, and the Nineteenth, giving women the vote, were adopted at least in part because of the war. Reformers began to talk about health insurance. The progressive campaign against prostitution and venereal disease gained strength, winning the enthusiastic support both of persons worried about inexperienced local girls being seduced by the soldiers and of those concerned lest prostitutes lead innocent soldiers astray. One of the latter type claimed to have persuaded “over 1,000 fallen women” to promise not to go near any army camps.

The effort to wipe out prostitution around military installations was a cause of some misunderstanding with the Allies, who provided licensed facilities for their troops as a matter of course. When the premier of France graciously offered to supply prostitutes for American units in his country, Secretary Baker is said to have remarked, “For God’s sake. . . don’t show this to the President or he’ll stop the war.” Apparently Baker had a rather peculiar sense of humor. After a tour of the front in France, he assured an American women’s group that life in the trenches was “far less uncomfortable” than he had thought and that not a single American doughboy was “living a life which he would not be willing to have [his] mother see him live.”

World History

World History