The Italian peninsula can be divided into three politically distinct regions. In the south the Hohenstaufen regno ('kingdom') collapsed after the battles of Benevento and Tagliacozzo and the death of the last Hohenstaufen heirs of Frederick II, his grandson Conradin and his illegitimate son Manfred. By 1268 the regno had passed to Charles of Anjou, the younger brother of Louis IX of France. Charles had been invited to intervene in the regno by the papacy and the 'Guelph' alliance between Charles and the papacy resulted in the cession of Benevento to the papacy after 1263. Once established in the south Charles sought to dominate the north too, by uniting Guelph factions in Lombardy and by assuming the lordship of several Tuscan towns. He also secured influence in Rome. His domination of Italy collapsed, however, following the massacre of French Angevins in Palermo and across the island of Sicily at Easter 1282, an event known as the Sicilian Vespers. The Angevin dynasty continued to hold sway in Naples until the fifteenth century but Sicily now passed to King Pere II of Aragon, whose wife Constance was the daughter of Manfred. The ensuing War of the Vespers between the Angevins and Aragonese was to last for ninety years. Pere's son Jaume later also acquired Sardinia and Corsica from the papacy.

In central Italy the papacy had emerged as the leading political force and Ferrara, Bologna and the towns of the Romagna were formally ceded to the papal states by the emperor-elect Rudolph of Habsburg in 1278. A series of short pontificates, however, weakened papal authority in this region. In an attempt to retrieve the situation Boniface VIII (1294-1303) appointed Charles of Valois, brother of Philip IV of France, as vicar of the papal state but his success in reasserting papal authority was limited. Boniface also attempted, with greater success, to establish members of his Caetani family in the Roman hinterland as a basis for support. But this policy alienated others, notably the Colonna family, and in 1303 it joined the now hostile French in kidnapping the pope at Agnani.

Unable to pacify the papal state, the papal court was transfered to Avignon in 1307.

In the north, meanwhile, commerce flourished but political factionalism was rife in the vacuum caused by the demise of imperial power. Ostensibly, at least, much of this conflict (both between and within towns) assumed the guise of a contest between 'Guelph' and 'Ghibelline' powers: the pro-papal Guelphs deriving their name from the old Welf opponents of the Hohenstaufen in Germany while the proimperial Ghibellines derived theirs from the Hohenstaufen castle of Waiblingen. In the 1250s the papacy led a crusade against Ezzelino da Romano and Oberto Pelavicini (Pallavicini), who, disguised as imperial vicars, between them controlled Cremona, Pavia, Piacenza, Vercelli, Verona, Vicenza and Padua. Ezzelino was killed but, by opportunely changing sides, Oberto built up an even stronger lordship, which briefly included Milan. Thereafter control of that city alternated between the Ghibelline della Torre (1263-81) and Guelph Visconti factions (128195). In Tuscany conflict polarized between traditionally Guelph Florence, defeated at Montaperti in 1260, and traditionally Ghibelline Siena. In reality attachment to these parties depended more on local rivalries than wider loyalties, but the parties did at least provide a measure of cohesion to a politically fragmented region. Elsewhere Pisa, Genoa and Venice fought to defend their trading interests: the Genoese defeated the Pisans at Meloria in 1284 and the Venetians at Curzola in 1298. In the north-west Gugliemo VII of Monferrato extended his power over Piedmont by acquiring authority in Alessandria, Asti, Turin and elsewhere, while in the north-east an alliance of 1262 between Verona, Padua, Treviso and Vicenza was designed to prevent the dominance of one person in any of these cities. Nonetheless, Verona and later Vicenza fell to the della Scala family, Treviso to the da Camino and Padua to the Carrara.

F. Andrews

The Ostsiedlung

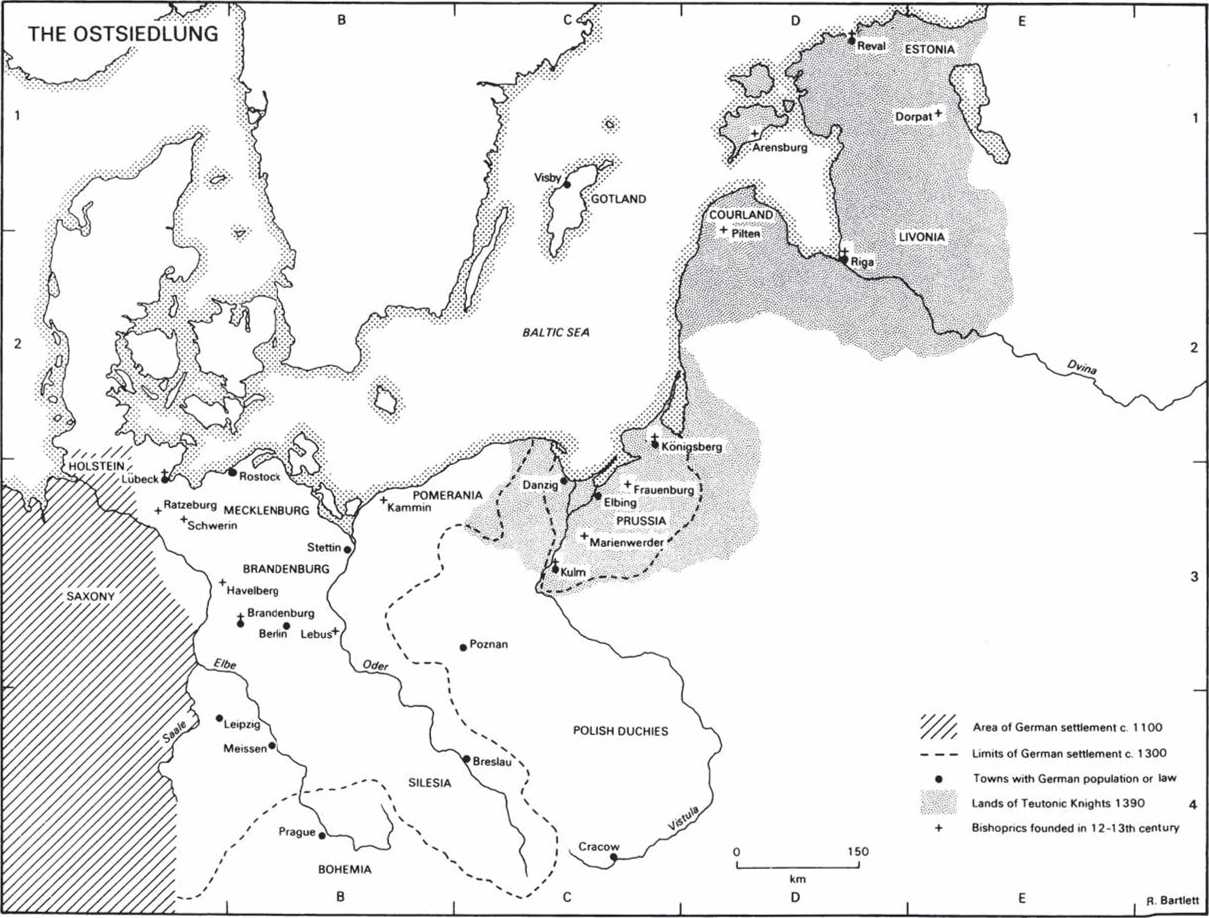

Between 1100 and 1350 eastern Europe was transformed by a wave of German immigration (the Ostsiedlung), which moved the eastern boundaries of the German-speaking world hundreds of miles beyond its former limit on the rivers Elbe and Saale. In some areas, such as Brandenburg, this new settlement came in the wake of conquest by German lords and knights, but in many other regions, such as Pomerania and Silesia, it was local Slav princes who encouraged German settlement. National antagonism was not important. The new settlers wanted land and the local rulers were happy to grant it and to profit, directly or indirectly, from the taxes, rents and tithes flowing from the new villages.

The frontier of settlement began to move in the first half of the twelfth century when immigration was actively promoted by such vigorous border lords as Adolf of Holstein, Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony, and Albert the Bear, margrave of Brandenburg. They advertised the attractions of the eastern frontier among the overcrowded inhabitants of western Germany and the Low Countries and soon streams of colonists were arriving in east Holstein, Schwerin, Ratzeburg and Brandenburg. The pace quickened in the thirteenth century as planned and large-scale development was undertaken in Pomerania and the Polish lands.

Rural settlement often involved the lay-out of entirely new villages, composed of standard, rectilinear farms (Hufen or mansi). The recruitment and organization of the colonists was the task of a planning entrepreneur (locator), who received land and privileges in the new settlement as his reward. Slav peasants were not usually dispossessed (though there are some instances of this), since in general there was plenty of land, especially for those willing to drain marshes or fell forests.

Rural settlement was complemented by new urban foundations. German burgesses formed the core of most of the new chartered towns founded in eastern Europe in these centuries. They brought their language, culture and law with them. Places as significant for German civilization as Lubeck, Berlin and Leipzig were twelfth - or thirteenth-century foundations in previously Slav landscapes. German urban settlement spread far beyond the limits of German peasant settlement and up to the borders of Russia there were German burgesses, living according to German town law, in the midst of native rural populations.

In some regions German conquest and settlement coincided with conversion to Christianity. The Slavs who inhabited Mecklenburg and Brandenburg, for example, were pagan until the twelfth century. In most areas, however, Germans came to lands that were already Christian. But one German settlement was unique in being created and permanently maintained by holy war. This was the domain of the Teutonic Knights, Prussia and Livonia, where German crusaders brought forcible baptism to pagan Baltic peoples. By the fourteenth century, although the pagan Lithuanians were far from being defeated, a German population of landlords, churchmen, burgesses and (in Prussia) peasants had settled, from Danzig to the Gulf of Finland, under the rule of the crusading knights.

The end result of the Ostsiedlung was the Germanization of vast areas east of the Elbe and an increase in their economic productivity. Some of the political units created in the process, like Brandenburg and Prussia, were to have an important role in subsequent European history.

R. Bartlett

World History

World History