The Plantagenet Dynasty

The Plantagenet or Angevin kings were a long line of fourteen monarchs whose reigns, stretched from the accession of Henry II in 1154 to the death of Richard III in 1485. They originated from the French county of Anjou centered on the city of Angers in the lower Loire Valley. Anjou corresponds largely to the present-day departement of Maine-et-Loire. From the 10th century, the Angevin counts pursued a policy of expansion, leading to the conquest of neighboring territories including Saumur, Touraine, Maine, and Normandy in 1145.

The name Plantagenet was originally the nickname given to Count Geoffrey of Anjou (1113-1151), father of Henry II, because of the gay yellow broom flower which he wore on his helmet. In time this emblem was embodied in the family heraldic arms. The Plantagenet period stretched over the whole Middle Ages, and obviously British castle design gradually evolved from the 12th to the 15th century in order to meet administrative, cultural and, of course, military requirements.

Henry II

Few kings of England have done such lasting work as Henry II. He found a land in a state of chaos and confusion, and left it with a system of government and a habit of relative obedience that were able to keep the peace long after his death. On his accession to the English throne in 1154, the masterful young King Henry II restored the royal power, which had been greatly harmed during Stephen’s reign. He ordered the wholesale destruction of all unlicensed, illegal or “adulterine” castles, sent off the mercenaries, and deprived many earls who had been created by Stephen and Matilda of their titles. Henry II’s task was a difficult one, but the new king had a strong will, a fierce temper, indefatigable energy and quickness of mind. He restored order in

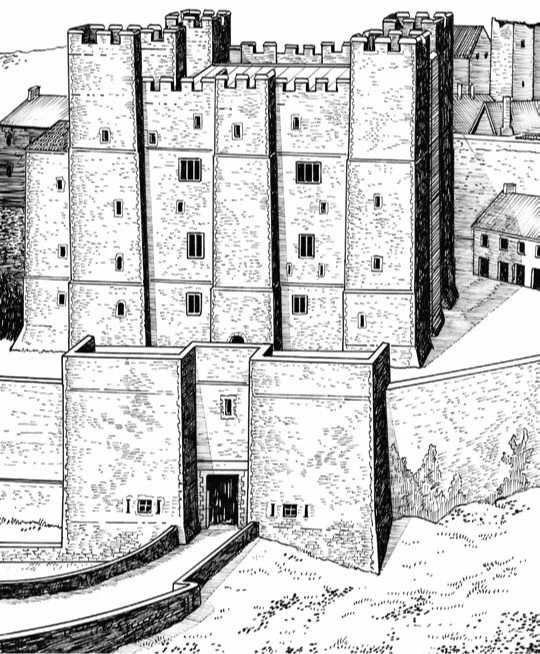

Above: Dover Keep. Strategically located in the Strait of Dover facing Calais in France, Dover has always been regarded as the key access from the Continent to Britain. This is clearly demonstrated by an outstanding series of fortifications which go back over 2,000 years. Archaeogical evidence shows that Dover was a maritime center as early as 1300 b. c. in the Bronze Age. Traces of a Celtic Iron Age hill fort have also been found in the actual castle. The port, called Dubris, was founded by the Romans in a. d. 43 and was a base for the Roman fleet operating in the English Channel. By the mid-10th century, Dover had its own mint and was a flourishing harbor trading with northern France. The keep of Dover, today the central feature of a whole complex of fortifications, was built between 1181 and 1188 at the time of Henry Il’s reign (1154-1189) by the master-builder Maurice l’Ingenieur. The massive keep clearly shows the continuity of the traditional Norman keep. It is the latest and largest of the 12th-century keeps. It is virtually a cube in shape: 98 by 97 feet (approx. 30 m) in plan, and 95 feet (28 m) high. Its walls are unusually thick, varying from 17 to 21 feet (approx. 6 m), allowing many mural chambers, galleries and staircases. The internal arrangement includes a basement, middle storey and main floor. Entry was at the main level through an elaborate forebuilding. The keep was hemmed with a curtain wall with a square tower enclosing an inner bailey.

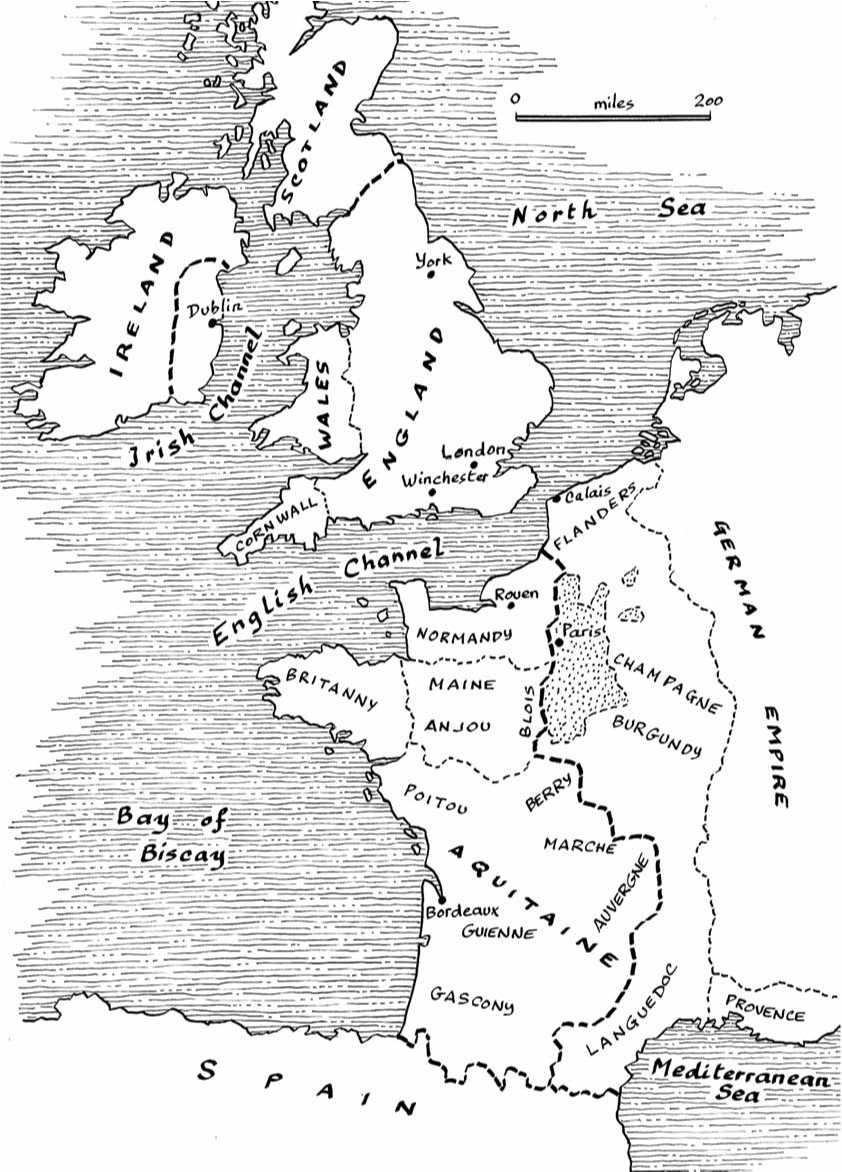

Opposite: The Plantagenet Empire. The Angevin Empire at its peak stretched from south Scotland to the Pyrenees. Henry II had inherited Anjou, Touraine and Maine from his father Geoffrey, and Normandy, England, the southern part of Wales and the western coast of Ireland from his mother, Queen Matilda of England. The large territories in southwest France (including Poitou, Berry, Marche, Auvergne, Aquitaine and Gascony) he had acquired by his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152. Brittany was gained by his son Geoffrey’s marriage to Duchess Constance of Brittany. Only the lands around Paris (known as Ile-de-France) belonged to and were directly ruled by the French Capetian kings. Flanders, Champagne, Burgundy, Toulouse, and Languedoc were large independant principalities recognizing the Capetians as overlords.

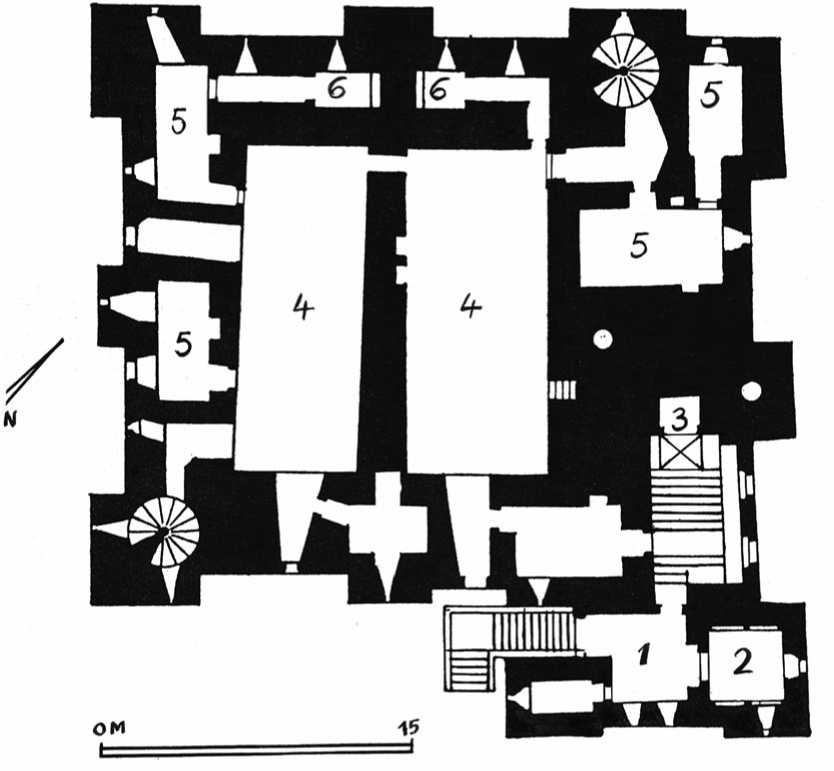

Above: Groundplan of Dover keep. The plan shows the second story of the keep. 1: Entrance; 2: Chapel; 3: Drawbridge; 4: Halls; 5: Chambers; 6: Galleries and latrines.

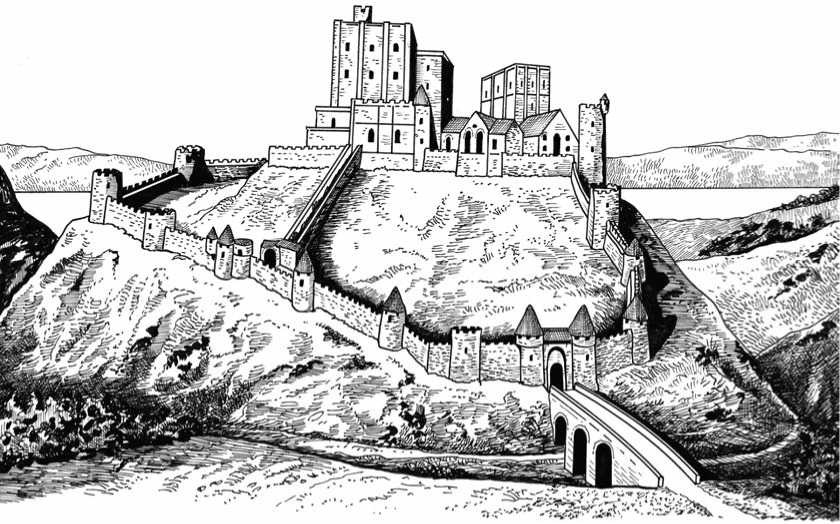

Opposite top: Dover Castle c. 1300. During the reigns of King John (1199-1216) and his successor Henry III (1216-1272), much additional work was done on the outer defenses, and by 1256 Dover Castle had reached most of its present day extent and appearance. Although Norman and conservative in design, the general concept of Dover castle is advanced, being that of a concentric castle, which uses a system of defense consisting of two independant walls. Although the medieval town walls no longer survive, Dover Castle continued in use beyond the Middle Ages and later additions (seaforts, redoubts, linear entrenchments, coastal batteries, and concrete bunkers and shelters) from the 16th to the 20th centuries display an impressive history of British military architecture.

Opposite bottom: Plan of Dover inner bailey. 1: Keep; 2: King’s Gate; 3: Northern Barbican; 4: Service buildings; 5: Hall; 6: Palace’s Gate.

England and reconstructed the English legal system, and at the same time ruled the wide realms on the continent which he had either inherited or gained through his marriage with Eleanor, heiress of the dukes of Aquitaine. Henry II was indeed one of the most powerful kings in Europe, ruling all the lands between Scotland and Spain. He received all of northwest France from his father and all of southwest France from his wife. Ruling an empire greater than that of any English king before him, he was a figure of European stature, comparable in prestige to the German Emperor Bar-barossa. Although he spent the greater part of his reign across the Channel, he still

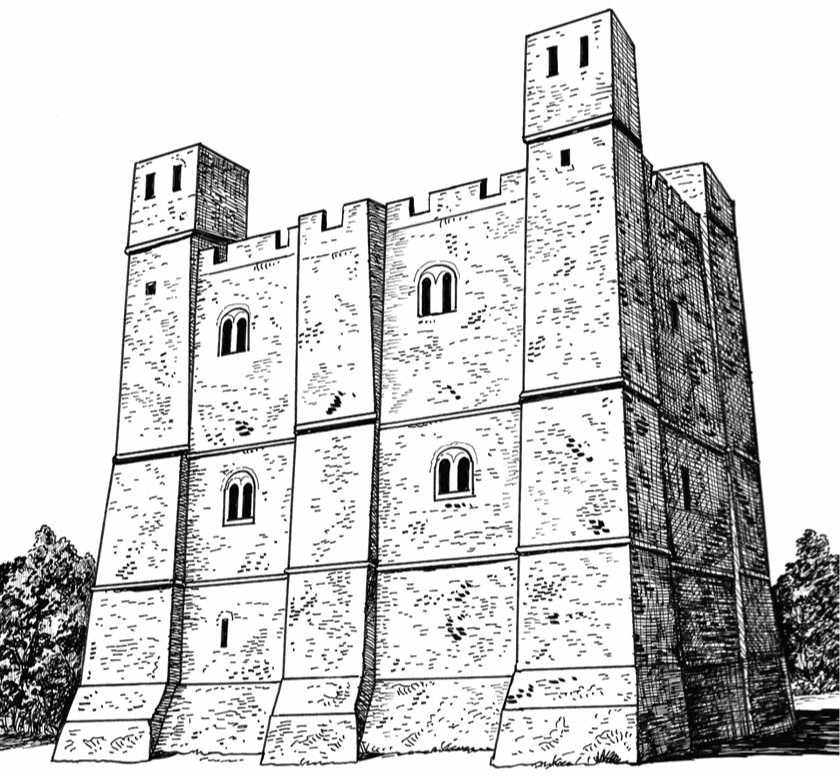

Chambois Donjon. The keep of Chambois, located near Trun in Orne, Normandy, was built in the second half of the 12th century. Its construction is probably the work of Guillaume de Man-deville, who was loyal to the English King Henry II. After 1204, the castle was given by Philippe-Auguste to his marshal Henri Clement. This rectangular keep (21.4 m by 15.4 m from the exterior) is the best preserved in Normandy. Its walls are intact and rise to 25.7 m; their summit was given a gallery of machicolations and crenellations in the 14th century. The castle was originally surrounded by a wall, which was destroyed in 1750.

Found time to be one of the greatest of all England’s rulers. Henry II triumphed brilliantly over the nobility, but he was in turn worsted by the Catholic Church, and his reign was embittered by the famous struggle and clash with his chancellor, archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket. Henry II’s sons, Richard and John, continued their father ‘s policy but with much less success, and the uneasy and unresolved relationship between France and England led to generations of conflict.

Crusading knight. Warriors of the First Crusade in 1099 differed little from William the Conqueror’s knight in 1066. Gradually some changes appeared, though, including a close helmet and a cloak or surcoat worn over the chainmail hauberk.

Richard I

Henry II was succeeded by his son Richard I. Handsome, gay, frank, open and generous, a patron of poets, Richard was a complete cosmopolitan military adventurer, a chivalrous knight, a restless wanderer, an able general, and a tough crusader. Richard I, nicknamed Coeur de Lion (the Lionheart), however, played a very small part in the internal affairs of England, spending only ten months in the realm during his ten-year reign from 1189 to 1199. Otherwise, he was campaigning in France, Sicily and Palestine. Richard was also a castle builder who ordered the construction of the formidable Chateau Gaillard in Normandy and made additions to the Tower of London. Though his prowess in the field aroused wonder, Richard was no statesman. Despite his excellent reputation, as King of England he was a disaster, a thoroughly bad king. War was his delight and he drained the country to near bankruptcy because he regarded his kingdom only as a source of revenue. His subjects paid for his extravagant and chivalric exploits—notably they had to finance a huge ransom when the wandering king was captured by the duke of Austria in 1192 on his way back from

Palestine. Although the government of the realm was fortunately in the hands of capable deputies who successfully combated the ambitions of his brother John and the intrigues of the nobility, Richard’s absentee rule ushered in a weakening of the royal power. The careless and glamorous Richard died childless in 1199, aged 42, and was buried at Fontevrault in Anjou, France.

John

It fell to Richard’s brother, John, to meet the series of internal upheavals and external assaults, which inevitably assailed the unmanageably vast Angevin empire. Tradition has exalted the memory of Richard I and denigrated that of John. A striking contrast to his brother, John was a thoroughly unpleasant man, cruel, lustful and debauched, unreliable, treacherous, avaricious and lacking prestige. John, nicknamed “Lackland,” has often been regarded as the archetype of the wicked and bad king. During his 17-year reign, from 1199 to 1216, he worked hard at the business of government, but his ventures were complete failures. The articulate elements of society, both clerical and lay, united against John clashed with Rome, causing England to be placed under papal interdict from 1209 to 1213. Unsuccessful as a general, out-maneuvered by King Philippe of France, he burdened his people with taxes. English barons, dissatisfied with his erratic rule, forced him to concede a list of privileges—

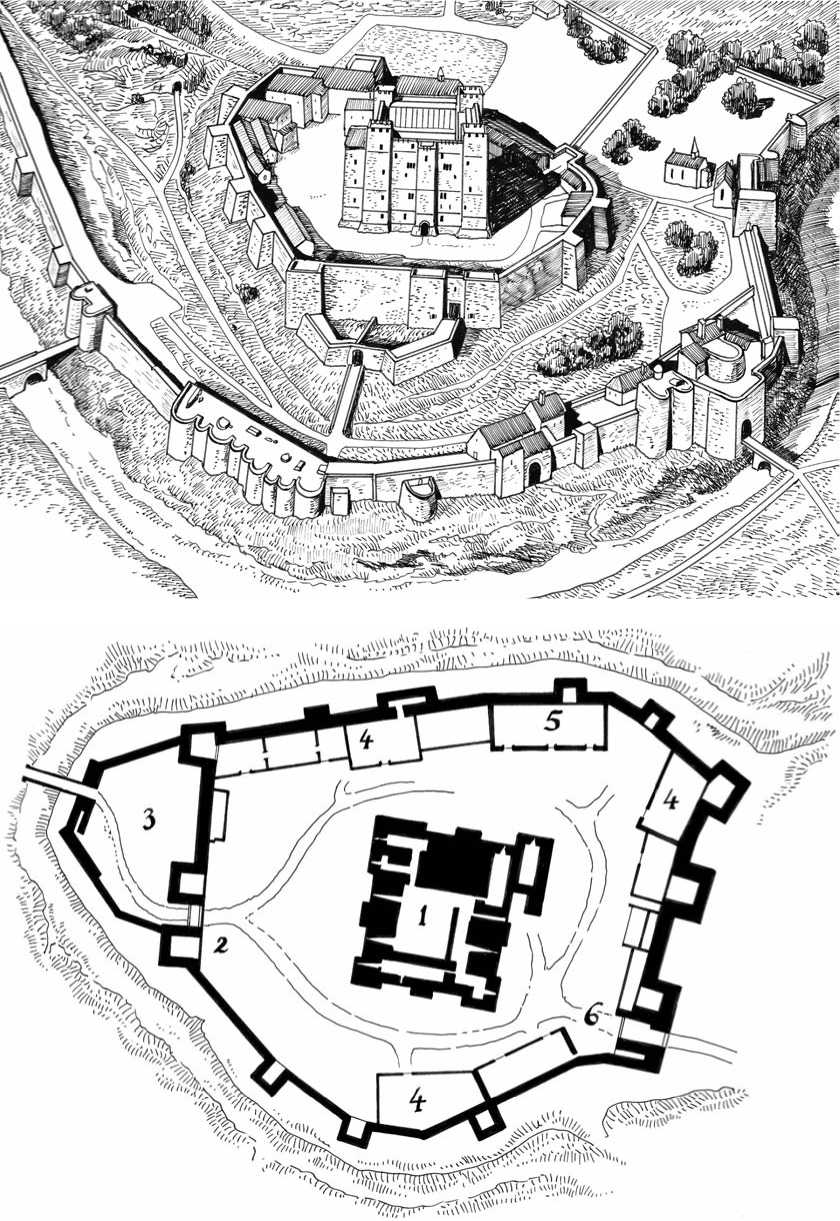

Opposite top: Chateau-Gaillard (conjectured reconstruction), located along the Seine River on a steep cliff extending above the towns of Grand and Petit Andelys in the Eure departement in Normandy, was built in an amazingly short time in 1196-1198 by order of Richard I. It was an imposing castle intended to deter King Philip Augustus of France from invading Richard’s Norman territories, and to act as a base from which Richard could launch his campaign against the French. Richard was particularly proud of the fortress and boasted when it approached completion in 1198: “Behold, how fair is this year-old daughter of mine!” The castle became Richard’s favorite residence, but the king of England did not enjoy the benefits of his “daughter” for long, however, as he died in Normandy on April 6, 1199, from an infected arrow wound to his shoulder, sustained while besieging the castle of Chalus. In 1203, Philip II Augustus laid siege to the stronghold of Chateau-Gaillard and took it. With the castle under French control, the main obstacle to the French entering the Seine valley was removed. They were able to attack and take Normandy. The city of Rouen surrendered to Philip II in June 1204. After that, the rest of Normandy was easily conquered by the French. Thus, for the first time since it had been granted as a duchy to the Viking Rollo in 911, Normandy was directly ruled by the French king. Much later, in 1599, Henri IV of France ordered the demolition of Chateau-Gaillard. Although it was already in ruins at the time, it was felt to be a threat to the security of the French realm. Today the castle ruins are listed as a Monument Historique by the French Ministry of Culture and are open to the public.

Opposite bottom: Plan of Chateau-Gaillard. The castle was a remarkable fortress with features well ahead of its time. In building it, Richard put into practice ideas which he had brought home from the Crusades. It consisted of three wards. The triangular outer ward (1) served essentially as a barbican, for to gain access to the castle, attackers had to go through the outer ward first. A dry rock-cut ditch (2) separated the middle and outer ward, the two connected by a fixed bridge. The middle ward (3) included the entrance, a large chapel, latrines, stables, workshops, and storage facilities. The inner ward (4), laid out at the end of the spur near the cliffs, housed the living quarters and the almond-shaped keep (5).

The famous Magna Carta of June 1215, the “cornerstone of English liberties,” which limited the monarch’s power. John’s greatest problem was the disloyalty of his barons, particularly the vassals of his French possessions, who were bound to develop French rather than English allegiances, and after the fall of Chateau Gaillard, Normandy was reunited with the French throne in 1204. The universally hated John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son, Henry.

Henry III

After a regency by capable deputies, the young Henry III (born in 1207) started to rule in 1227. Henry was a weak man, who under the pressure of the English nobility

Standing on a steeply sloping hill above the village of the same name in the county of Dorset, the strategically sited Corfe Castle commanded a gap in the Purbeck Hills on the route between Wareham and Swanage. The oldest surviving structure on the castle site dates to the 11th century, although evidence exists of some form of stronghold predating the Norman conquest. Construction of a stone hall and inner bailey wall occurred in the 11th century and extensive construction of other towers, halls and walls happened during the reigns of Henry I, John and Henry III. By the 13th century the castle was being used as a royal treasure storehouse and prison. Refortified in 1202-1204, the castle remained a royal fortress until it was sold in the 16th century by Elizabeth I to her lord chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton. The castle was besieged in 1646 by Oliver Cromwell’s force and destroyed by explosives and undermining to ensure that it could never stand again as a Royalist stronghold. In the centuries that followed, the local populace took advantage of this easy source of building material and masonry. Today the skeletal ruins of the castle dominate the village skyline and are open to public. The illustration, based on a 17th-century engraving, shows how the castle might have appeared before the siege of1646.

Was forced to accept the principle of consultation, concessions and compromises instead of absolute royal power. A series of crises strengthened the position of the baronage. In 1258 Henry was forced to accept a settlement known as the Provisions of Oxford, which effectively established a baronial council to regulate the king’s government. Under his weak rule, the Angevin Empire collapsed. It was formally buried by agreement with Louis IX of France (Saint Louis) in 1259, leaving only Gascony in English hands. Henry III loved splendor and display but lacked judgment and asserted himself more obstinately than shrewdly. He greatly admired Edward the Confessor, whom he somewhat resembled. He was a failure as a king, but he was a great patron of medieval architecture. Notably, Henry III transformed the Tower of London into a major royal residence and had palatial buildings constructed within the Inner Bailey to the south of the Norman keep. During Henry III’s long reign from 1216 to 1272, the plain, massive style of the Normans gradually gave way to the elegant Gothic style. Henry III died in 1272 and was succeeded by his son Edward I. With Edward began an important period in the evolution of British castles, and it

Liverpool castle, which occupied a prominent site overlooking the Mersey, was probably erected under the orders of William de Ferrers, earl of Derby, between 1232 and 1237. The most detailed medieval account was made in 1347, which described the castle as having “four towers, a hall, chamber, chapel, brewhouse and bakehouse, with a well therein, a certain orchard and a dovecot.” It was surrounded by a dry moat. Owing to the development of the city, the castle was dismantled and the last vestiges had disappeared by 1726.

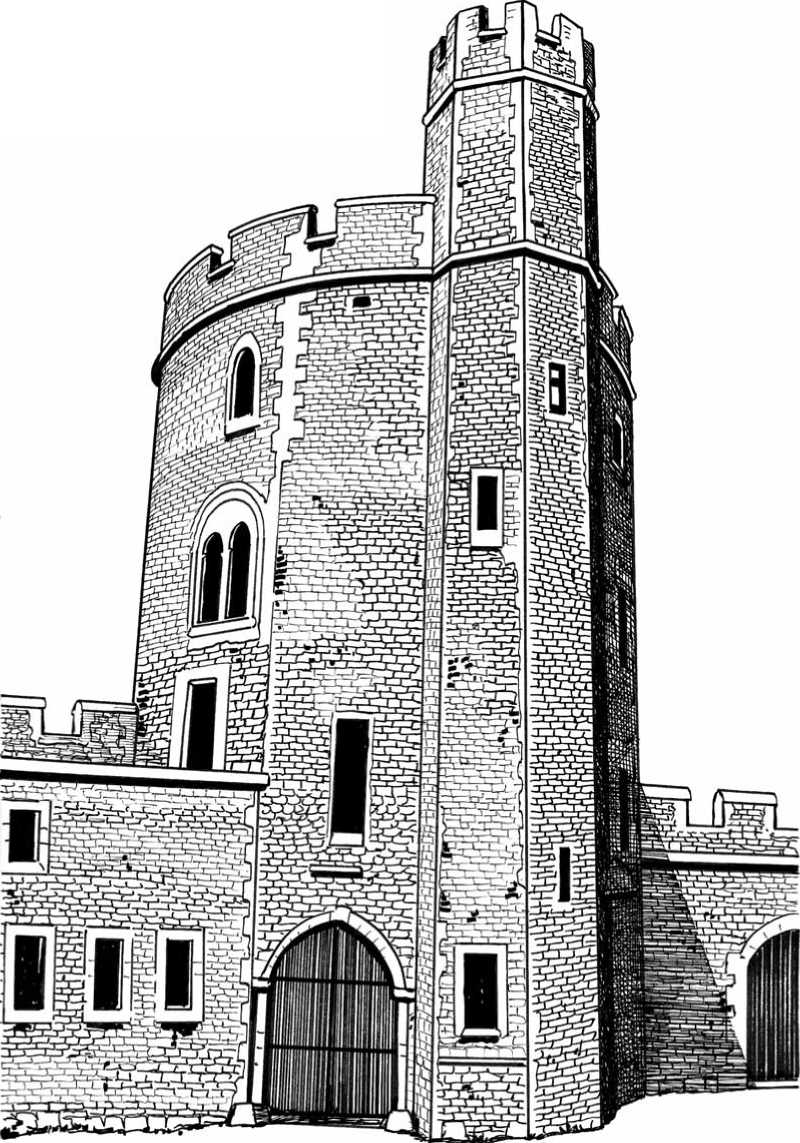

Lanthorn Tower in the Tower of London was constructed between 1238 and 1272 by order of King Henry III. Its name comes from its use as a marker by nearby ships along the Thames via a lantern that was lit each night in the top turret. Lanthorn Tower was destroyed by a fire in 1774 and reconstructed in 1851.

May be useful, before dealing with the formidable Edwardian castles, to take a break and see what progress siege warfare had made, and what evolution had taken place regarding castle design.

World History

World History