The strongest individual case is that of Carrigogunnell in Co. Limerick, granted to Donough O’Brien in 1210 (Empey, 1981, 14; Warren, 1981, 29). The site is a strong one, on an isolated rock on the southern shore of the Shannon estuary, but the castle is both ruined and overgrown. This makes its study the more difficult, for it is clearly a castle of several periods. It is interesting to note how the grant of this castle has been seen by historians as part of a demonstration of how Donough O’Brien was one of the most anglicised of Irish kings at the time, integrated into the English polity. Be that as it may, it is also significant that the castle remained in O’Brien hands for the rest of the century.

The English attacks north-west of Meath and in Connacht are well documented in the Irish Annals, notably those of Lough Key and Connacht. Lynn (1985; 1986) has drawn attention in particular to the information on castles in Connacht for a rather different purpose. There are a number of references to Irish use of sites, all of them on islands in lakes, fortified in some way and therefore to be considered in the context of the possible use of castles. In 1220 the Annals of Lough Key record William de Lacy’s attack on O’Reilly’s crannog, identified with the island in Lough Oughter (Orpen, Normans, III, 33). On this rocky island, which may have been extended artificially with piles (Kirker, 1890, 295), there is now a large circular tower, badly damaged by gunpowder during or following the siege of 1653 (Manning, 1990). In spite of the loss of a quarter of its circumference, this tower does not look like other round great towers of the period: it notably lacks windows or fireplace. It could be the work of O’Reilly, but the castle was apparently used by William de Lacy in 1224 as a refuge (Orpen, Normans, III, 43), and he may have built the tower. Unfortunately, excavation in 1987 shed no light on the earlier history of the tower (Manning, 1990).

Islands were apparently important in Connacht; as a sign of his defeat in 1225, O’Flaherty yielded up island forts in Lough Corrib, including Castle Kirke, to Richard de Burgh. In 1235, the forces of Richard de Burgh, engaged in the

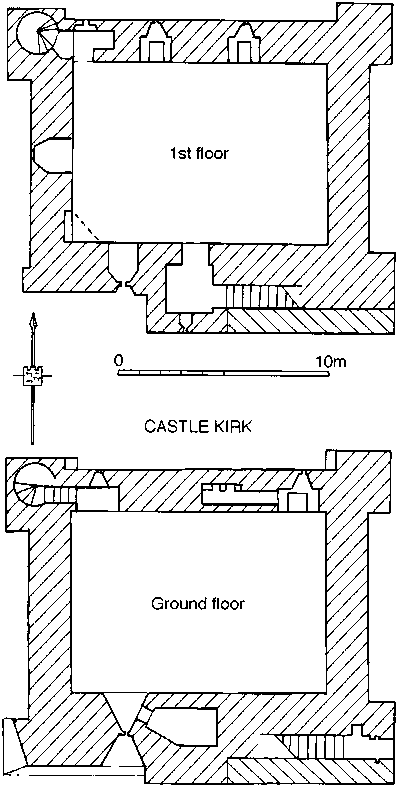

Figure 102 Castle Kirke: plans of the hall

Conquest of Connacht, attacked McDermot’s castle on one of the Lough Key islands. As well as bombarding it with stones from perriers mounted on the shore and on boats, they threatened to burn it using combustible rafts towed against it (Annals of Lough Key and Connacht; Orpen, Normans, II, 183-4). This might imply that the structure was fundamentally of wood, but the Annals of Connacht record that after its recapture by treachery, in 1235 McDermot threw it down and scattered its stones.

In 1233 the Annals of Connacht record that Fedhlim Ua Conchobair destroyed four castles (Galway, Dunamon, Hag’s Castle and Castle Kirke) which had been

Built by de Burgh and his Irish allies, the sons of Ruadhri Ua Conchobair: in 1232 the same Annals record that Galway and Dunamon castles were built by de Burgh and Adam de Staunton. The sons of Ruadhri may be credited, by implication, with building the other two. Hag’s Castle is a simple circular enclosure about 31-33 m (100 ft) across, surrounded by a wall up to 5 m (16 ft 6 in) high, built of massive stone blocks with some mortar: there are no features to it.

Castle Kirke is different. It is a rectangular building (Fig. 102), with pointed lancets and rear arches to the embrasures of the windows, undoubtedly of the thirteenth century. It is entered by a door in the first floor, from a stone stair which has been added to the southern side; it was guarded by a portcullis, whose slot survives at the base of the stairs. All this relates to the first-floor halls typical of the thirteenth-century English castles, but it shows variations. The angles are marked by turrets with base batter on the west. These do not provide extra space for rooms (except the north-western one, which accommodates a circular stair), nor do they project equally to be effective buttresses. This is especially noticeable on the northern side, closest to the lake where it most needs support; here the projection is least. The wicker-centred vault over the little room on the ground floor below the doorway may mark the presence of Irish workmen, but we have seen this elsewhere. It is on the rather anomalous plan of the hall and the presumed identification of this building with the one mentioned in the Annals, that we might identify Castle Kirke as an Irish version of an English hall-house castle.

World History

World History

![Road to Huertgen Forest In Hell [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432477693_1428700369_00344902_medium.jpeg)