The Priory of Castile became an appanage for over a century of the ducal house of Bejar, Don Alvaro de Zuniga gaining possession of the office in 1482. His nephew Antonio expected to succeed him, but when the time came his family’s influence was countered by that of the Duke of Alba; through the favour of King Ferdinand and the acquiescence of Pope Leo X, he had Don Diego de Toledo appointed, overriding the wishes of the Order. Zuniga refused to give up his claim, and at the time of King Ferdinand’s death Cardinal Cisneros was moving a royal army to eject him from the prioral lands. The dispute was resolved by the young Charles V, who ordered the Campo de San Juan to be divided between the two claimants (1517); Con-suegra became the residence of Zuniga as Prior of Castile, and Toledo enjoyed the palace of Alcazar de San Juan as nominal Prior of Leon, a division that continued until the death of the last of three successive Toledo brothers in 1566. As far as the Order was concerned the genuine

Prior was Zuniga, and he took care to retain royal favour by playing a leading part in suppressing the Comunero rebellion, reconquering the city of Toledo for the King in 1521.

A worse example of royal intervention was shown in Portugal, where in 1516 the King imposed a Knight of Santiago as Prior of Crato. After the fall of Rhodes the threat to the integrity of the Priory became even graver, but it was averted by the diplomacy of Villiers de I’lsle Adam, and in 1528 King John III paid the Order 15,000 crusadoes for its consent to seeing his brother Luiz installed as Prior. Dom Luiz (1506-55) was the most admirable of four royal brothers; he administered the Priory well and kept the rule of celibacy, being noted in his later years for his piety. In 1541 he founded a seminary of chaplains at Flor da Rosa and established at Estremoz the convent of nuns which had been founded at Evora in 1519. It took the rule of Sijena and occupied a fine building on the spacious square of St John, the main market-place of the city.

Unfortunately the product of Dom Luiz’s less regular youth was his bastard son Antonio (1531-95), who succeeded him as Prior. On the extinction of the House of A viz in 1580 he attempted to gain the throne against the claims of King Philip II. The Prior of Crato was an unprepossessing individual of licentious life, whose principal military exploit to date was to have been taken prisoner at the battle of Alcacer Quibir. The King of Spain had little difficulty in

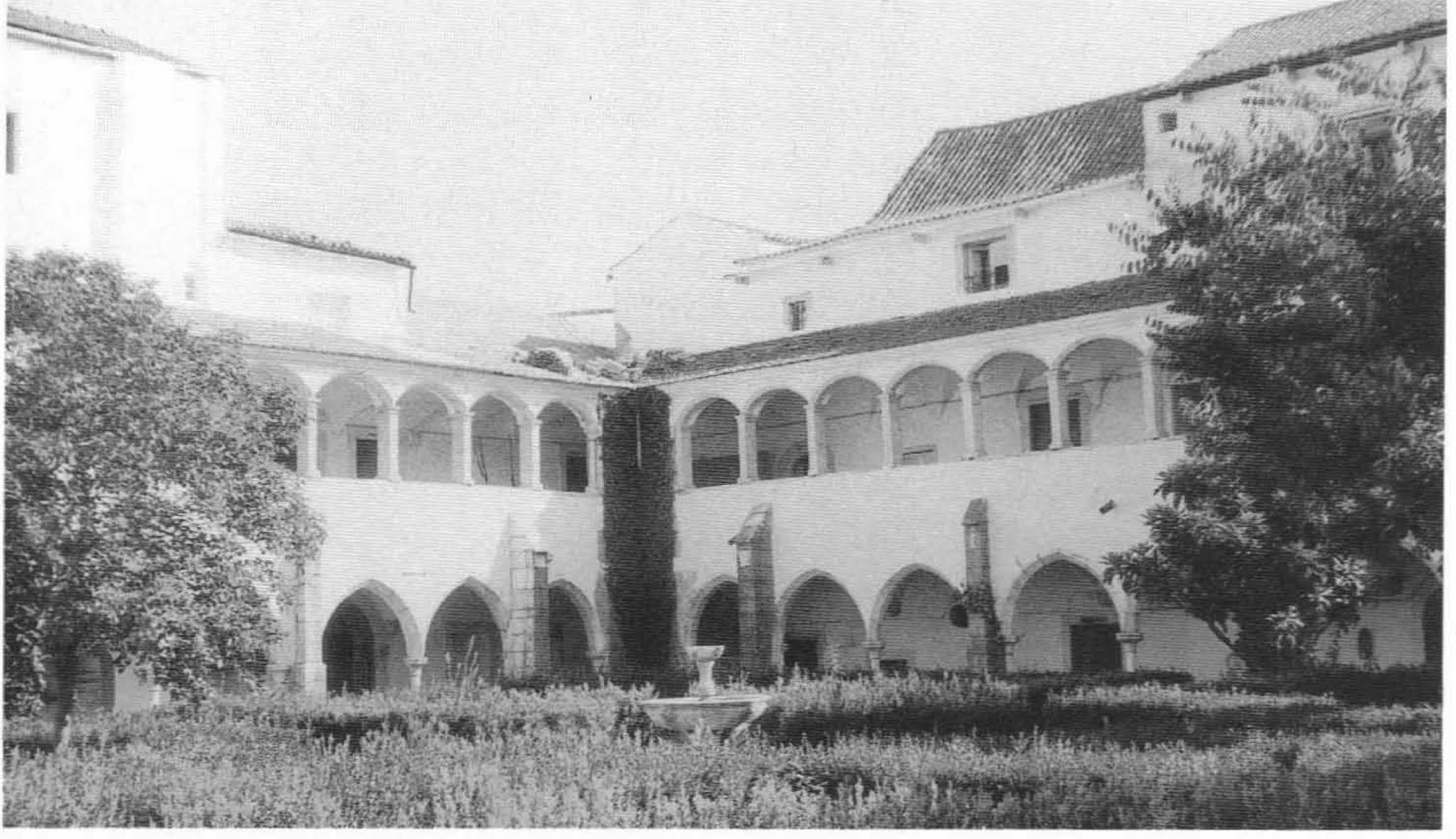

Convent of Estremoz (i6th century).

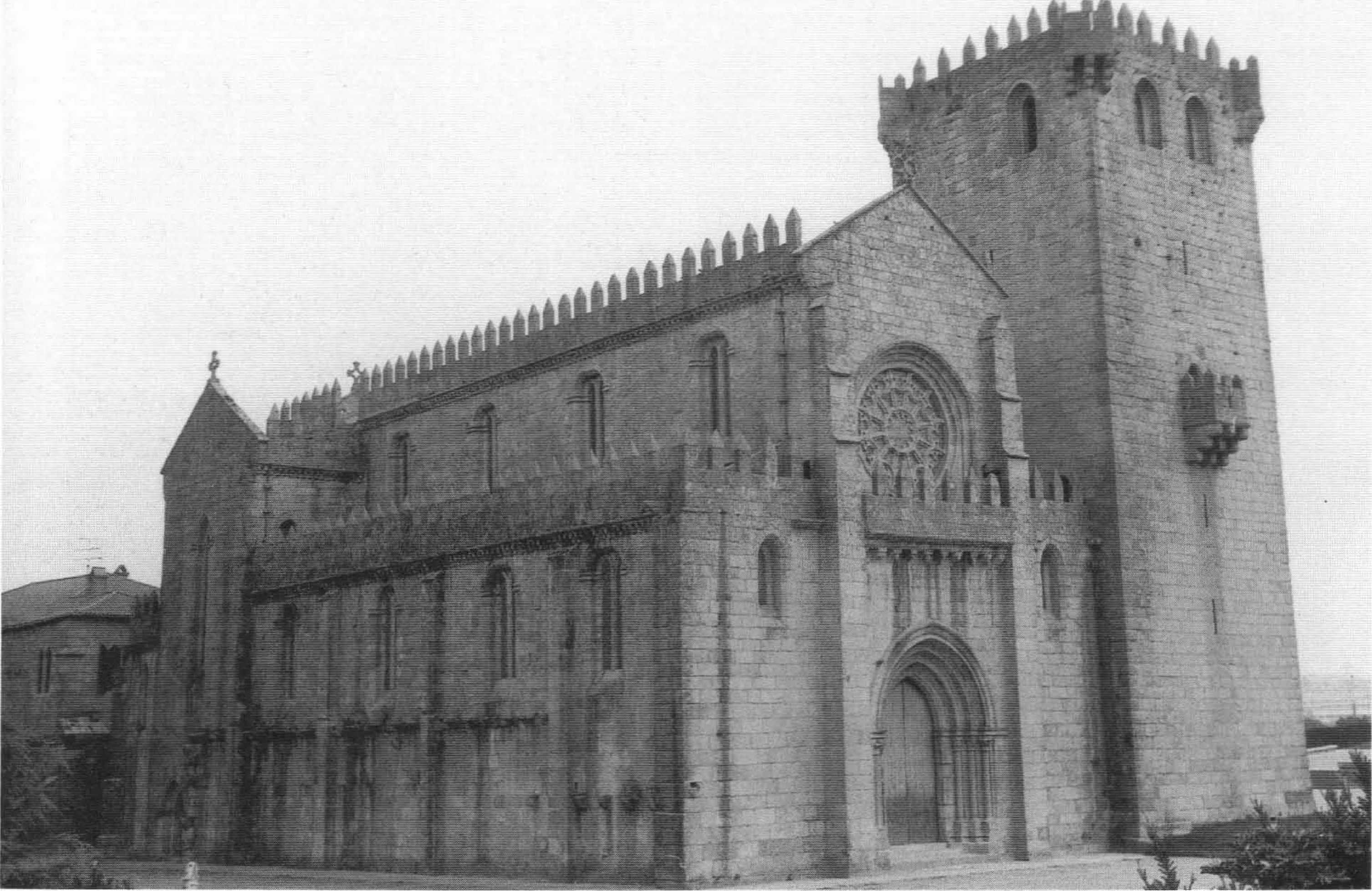

Lcqa: the Bailiff’s church, c - 1335-

Making good his title; Dom Antonio fled to England and in 1589 landed with Drake on the Portuguese coast in a further attempt to conquer the kingdom.* When this failed he withdrew to the protection of Henry IV, in whose dominions he ended his days.

His successor as Prior of Crato was the Cardinal Archduke Albert, known as ‘the Pious’ (1559-1621), who when only twenty-three was appointed Viceroy of Portugal. The ten years of his government did much to reconcile the Portuguese nation to Castilian sovereignty. He resigned the Priory, together with his cardinalate, on his marriage in 1599, and was succeeded by two princely absentees, Victor Amadeus of Savoy and the Cardinal Infante Ferdinand, famous for his leadership of the Spanish armies in the Thirty Years’ War. When the latter died in 1641 the Portuguese revolt against Spain had begun, and it was the House of Braganza which appropriated the right of nomination. The new King conferred the Priory on his third son, who was to seize the throne as Peter II in 1668. Three professed

Knights nominated by the King then held the Priory, and from the end of the seventeenth century it was reserved to a series of Infantes.

In view of the exclusion of the Portuguese knights from the prioral dignity, the titular Bailiwick of Acre was reserved for their nation about 1570 and was attached to the commandery of Le<;a, which, after Crato, had always been their most splendid possession. The fine church had been built about 1335 by Estevao Vasques Pimentel, one of the most distinguished Priors of the fourteenth century, and the adjoining palace became the residence of the Bailiffs, who were the real administrators of the Priory while princes enjoyed the revenues of Crato. The same circumstances may account for the prominence of the Portuguese in the government of the Order. Luis Mendes de Vasconcellos held the Grand Magistry for a few months (1622—23) after a career of great distinction, and in the eighteenth century Portugal produced two of

* This expedition, which involved a larger fleet and resulted in almost as complete a disaster as that of the Armada the previous year, sinks out of sight in the patriotic glow of ordinary English historiography.

Aragon and Castile

The most notable holders of that office, Antonio Manoel de Vilhena and Manuel Pinto da Fonseca.

In Castile the sixteenth century was the golden age of the Order of Malta. While the national military orders went into decline after the ending of the Reconquista and the annexation of their Masterships to the Crown, the grant of Malta and Tripoli by Charles V and the strategic cooperation of Spain and Malta gave new prominence to the Knights of St John. The Grand Mastership of the Aragonese Homedes came at an opportune time to assist the advance of his compatriots, but it was the Castilians who chiefly took advantage of it. This was especially true in the great surge of recruitment after the siege of 1565, when the Castilians came to exceed in numbers not only their Aragonese confreres but also the Knights of Calatrava and of Alcantara, and perhaps even those of Santiago, which otherwise held pride of place among the military orders of the kingdom.

The tenure by the Zunigas of the Priory of Castile ended in 1598, when Philip II nominated his grandson Prince Filiberto Emanuele of Savoy (1588—1624), younger brother of the contemporary Prior of Crato. The princes had been brought up in Spain but had been withdrawn when their father decided to follow the antiSpanish star of Henry IV. The assassination of that monarch in 1610 caused the Duke of Savoy to send Filiberto Emanuele on a hasty diplomatic mission to assuage the displeasure of the King of Spain, a task in which he was so successful that he was appointed Captain General of the Spanish navy. On this death the Priory was briefly held by two ordinary Knights of Malta, including another Zuniga, but then reverted to royal possession.

An incident of this period was the reception into the Order ofLope de Vega. The playwright’s vast oeuvre already assured him an unshakable position in Spanish letters, but he hankered after a less immortal distinction. He coveted the title of frey which was borne by the knights and chaplains of the military orders, and whose prestige is a sign of the position those orders held in the society of the time. Lacking the qualifications of nobility, he approached the papal nephew Cardinal Barberini on his visit to Spain in 1626, and two years later a dispensation from Pope Urban VIII enabled him to be admitted as a chaplain of the Priorv of Castile.

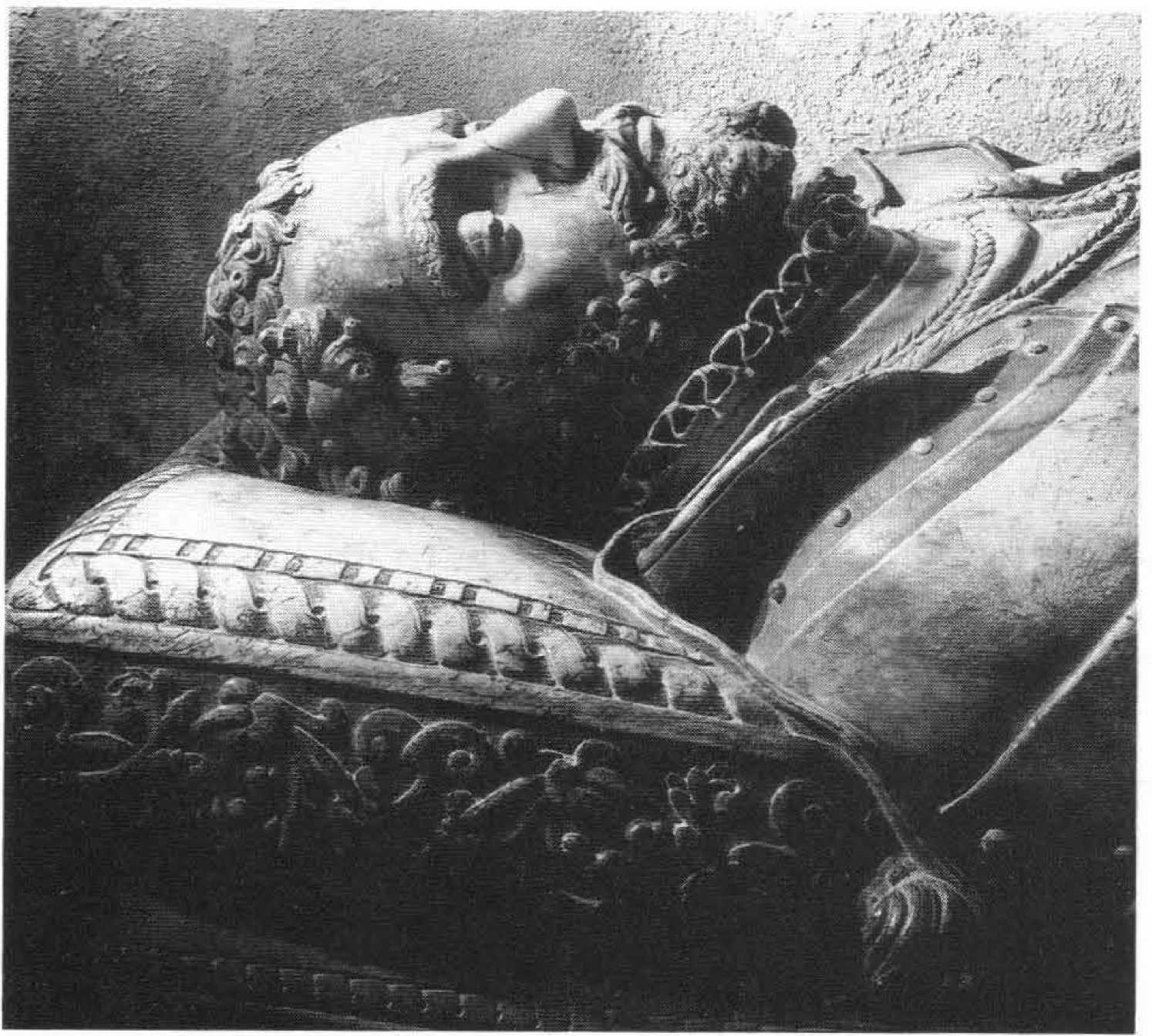

Tomb of the Knight of Malta Juan-Luis de Vergara (1575) from Valladolid Cathedral, now at St John’s Gate.

In 1642 Philip IV had the Priory conferred on his thirteen-year-old bastard, Don Juan Jose de Austria, who professed as a knight and grew up to be one of the most significant statesmen of the century. At the age of twenty-two, after four years’ proconsular experience in Naples, he was appointed Viceroy of Catalonia, where Spain was reimposing her rule after the serious revolt of 1640. The Catalans had delivered themselves to French sovereignty, but after eleven years’ experience of their liberators they received with joy the return of the House of Austria. During his five years there Don Juan pacified the principality and won the popularity which later made it the base of his political strength. From 1661 to 1665 he commanded with great skill the Spanish forces in Portugal, the only part of his father’s dominions whose rebellion had not been overcome. There can be little doubt that if he had not been starved of resources by the jealousy of Queen Mariana, who resented any glory won by her husband’s illegitimate son, this kingdom too would have been restored to the Spanish monarchy. On the death of Philip IV a struggle for power developed between Don Juan and Queen Mariana, who exercised the regency. He withdrew to Aragon, and his remembered popularity made him the first statesman in Spanish history to base his power on the eastern regions, from where he issued his pronuncia-mento against the Queen’s government. He failed to exploit his advantage, however, and contented himself with the government of Aragon. As the afflictions of the monarchy continued Don Juan became the idol of a swelling party which looked to him as the saviour ot the nation, and whose clamour enabled him to return, banish the Queen Mother and assume full power. His ministry from January 1677 to September 1679 was marked by valuable financial reforms, but his political projects outstripped the capacity of his exhausted country, and when he died, aged only fifty, he left the great hopes that had been held of him disappointed.

Don Juan’s successors as Grand Priors were the Marques de Tejada and, from 1687 to 1715, Francisco Fernando de Escobedo, a former Governor of Guatemala. He had devoted the greater part of his fortune to founding the hospital of Belen, but being accused of misgovernment he was dismissed, in the stringent fashion of Spanish administration, and was left so destitute that he was unable. to return to Spain to answer his accusers; the Order of Malta sent a ship to bring him back (1678) and the charges against him evidently failed, for he was appointed to the Council of the Indies, from which position he continued to render good service to Central America.

A more important political career was that of the Order’s ambassador in Madrid, Manuel Arias (1638-1717), who after serving as Pilier of the Castilian Langue took holy orders in 1690. His proposals for administrative reform caused Charles II, in a rare moment of independent decision, to appoint him in 1692 President of the Council of Castile. His honesty and ability struggled with some success against the political sickness of his age, and on the accession of Philip of Anjou (1701) he was called to second Cardinal Portocarrero in proposing sweeping reforms by which it was hoped to regenerate the Spanish monarchy. That this ambition failed is due to the twelve years’ war that the new King had to fight to defend his title, and partly also to the influence of the royal favourite the Princesse des Ursins, whose enmity for a time excluded Arias from government. Before that he had been placed second in rank in the Council of Regency, was appointed Archbishop of Seville (1702) and immediately offered the entire revenue of his see to confront the crisis of the war. He was restored 27

Bali Antonio Valdes (1744—1816) by Goya.

To ministerial office in September 1704 and eight years later received the cardinal’s hat.

After the death of Escobedo the Grand Priory of Castile again became reserved for royal nominees. Charles III, whose despotic conduct towards the Order of Malta had already been shown when he was King of Naples, appointed his second son, Don Gabriel, Grand Prior of Castile in 1766, and in 1785 he had that dignity, with its vast revenues of half a million reales, turned into a hereditary appanage of the cadet line, its connexion with the Order being thus severed in all but name. Four years later this measure was copied by the Portuguese royal house in regard to the Grand Priory of Crato.

Numerous knights distinguished themselves in the royal service, and the names of Jorge Juan, Amat, Bucareli, Guirior, Taboada, Grua Talamanca and Malaspina indicate that a student of the role of the Knights of Malta in the life of

Spain in the late eighteenth century would have a wide field of research before him. The most eminent representative of this generation is Antonio Valdes, who for thirteen years (1782— 95) held with great ability the office of Minister of the Navy, He later incurred the enmity of Godoy and was excluded from public service until he took up arms against the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. On the fall of the French regime Valdes was made Lieutenant of the Grand Priory of Castile and was one of the figures on whom the Lieutenancy of the Order could have depended, if its incapacity had not prevented it, to aid the restoration of the Spanish priories.

World History

World History