Railroad construction did not take off until the Porfirian state seized the initiative by providing hefty subventions to encourage British and U. S. investment and by promoting the development of the North.

Allen Wells, 200022

During the nineteenth century, the railroad occupied the same position that steel plants would occupy in the twentieth—it symbolized a better tomorrow. Rail fever swept over Mexico. In 1881, the Diario Oficial noted that it “was indeed with the greatest of enthusiasm that, in all sections of the country, the building of the railroads is being prosecuted.”23

For some, building railroads was practically a matter of faith. For others, it became the way to accumulate wealth. Bankers realized they could profit from the sale of securities and from lending for the purchase of railway equipment. Merchants and landowners favored the railroad because it would facilitate the production of commodities. For politicians, the railroad represented a way to increase the power of the state and win the support of constituencies via recourse to the pork barrel. The railroad also contributed to politicians’ personal wealth. For example, Manuel Romero Ancona, the governor of Yucatan between 1878 and 1881, found no conflict of interest when he granted concessions to two of the state’s rail lines and then served on their boards of directors.24

Throughout the Porfiriato, festivities accompanied the opening of a rail line. In 1892, Oaxacan businessmen raised 40,000 pesos for a fiesta to celebrate the driving of the last spike on the line to their city. President Diaz, Interior Secretary Manuel Romero Rubio, the British contractors, and a carload of newsmen traveled to Oaxaca City for the inauguration ceremonies. In 1907, an even more elaborate inaugural bash celebrated the opening of the rebuilt Tehuantepec Railroad. Four special trains carried guests, including Diaz, three state governors, ambassadors, and other diplomatic representatives. The event received national and international coverage from newsmen, who were provided with their own special train.25

While virtually all policy makers favored railroads, heated debate erupted concerning questions raised by rail construction. Many Mexicans warned that if rail lines connected the United States and Mexico, Mexico would be overwhelmed by the Colossus of the North. In 1878, Deputy Alfredo Chavero argued eloquently in Congress against building rail lines to Mexico’s northern border:

You, the deputies of the States, would you exchange your beautiful and poor liberty of the present for the rich subjection which the railroad could give you? Go and propose to the lion of the desert to exchange his cave of rocks for a golden cage, and the lion of the desert will reply to you with a roar of liberty.26

President Lerdo de Tejada initially shared this fear of being overwhelmed by the United States. Eventually, though, he concluded that rail links to the United States would lead to economic expansion in Mexico, which, in turn, would provide the strength to resist the United States.27

Paying for railroad construction provided the political elite with a conundrum. After the fall of Maximilian, Juarez promised the Imperial Railroad Company, Ltd. a 560,000-peso annual subsidy, agreed to purchase 3.7 million pesos of the company stock, granted the company the right to import material duty free, and exempted it from numerous taxes so it would continue construction of the Veracruz—Mexico City line. To avoid any delay in the construction of the railroad, Juarez made an exception to his policy of canceling all concessions granted by Maximilian. The British-managed Imperial Railroad Company, which had received its initial concession from the emperor, was allowed to continue construction.28

Subsequent administrations turned to domestic sources of financing after concluding that allowing foreigners to build railroads would inordinately increase their influence in Mexico. During Diaz’s first administration, the federal government built thirty-one miles of line, but then ran out of resources. President Gonzalez also attempted federally financed rail construction, but could only muster funds to build twenty-four miles of line.29

The federal government encouraged states to build rail lines. Between 1877 and 1880, states received twenty-eight concessions to build rail lines. However, the only significant construction occurred in Morelos and Guanajuato, where a total of ninety-two miles of track was laid.30

The Mexican private sector proved equally incapable of carrying out railroad construction. Between 1860 and 1880 eleven concessions were awarded to private Mexican interests to build railroads. Only one, in Hidalgo, was completed. Despite attempts to raise money through such novel means as a lottery, the capital and managerial requirements of rail construction overwhelmed Mexican builders, private and public.31

By the end of Diaz’s first term, it had become apparent that if Mexico was to have railroads within the near future, foreign interests would build them. To entice foreigners to build railroads the government had to ensure construction in Mexico was more attractive than in Cuba, Argentina, or the United States, which were rapidly expanding their rail networks. The government attracted foreign rail companies by offering subsidies that ultimately paid a quarter to a third of construction costs. As one of his last acts during his first term, Diaz granted the U. S.-owned Central Railroad Company a concession to build a rail line connecting Mexico City with El Paso, Texas. The concession included a subsidy of

7,000 pesos per kilometer of track completed. In addition to cash subsidies, rail builders were promised bonds, generous land grants, and certificates that could be used to pay customs duties.32

Since Mexicans could not finance rail building and Europeans were reluctant to invest in Mexico, the United States supplied 80 percent of the capital used to build Mexico’s major railroads. By 1883, the Central Railroad Company was employing 22,000 workers in rail construction. Employing such large numbers of workers on projects before they began to yield revenue required access to vast financial resources. The amount required exceeded the resources of individual U. S. companies. The Central Railroad and the National, which received the concession to link Mexico City and Laredo, Texas, sold shares on the Boston and New York exchanges to raise capital. When funds raised there proved insufficient, they turned to the London exchange. The government paid roughly 40 percent of the construction costs of the Central Line.33

The use of foreign capital permitted the more rapid development of railroads and allowed Mexicans to invest their scarce capital in other areas. Sometimes the generous subsidies promised by the government remained unpaid, because in times of financial crisis the amount pledged exceeded available funds.34

Once the decision had been made to allow foreigners a dominant role in rail construction, rail mileage soared. When Diaz first took office, Mexico had only 416 miles of track. In 1884, Mexico City was connected with El Paso, Texas, amid predictions that the new line would stimulate the Mexican economy and open new markets for U. S. products. By 1910, rail mileage had soared to 11,954 as political stability and generous government subsidies attracted foreign capital and innovations in metal production (such as the Bessemer process) reduced the cost of steel.35

Between 1878 and 1910, the railroad produced an 80 percent decrease in freight costs. to the railroad, the cost of shipping a ton of cotton goods from Mexico City to Queretaro declined from $61 to $3 between 1877 and 1910.36

While the cost of transport plunged because of the railroad, setting rail rates would have challenged Solomon. Since the first Veracruz—Mexico City rail line had a monopoly, it charged almost much as muleteers did. The British consul candidly observed that a railway “that could be beaten in point of cheapness by pack animals is naturally not the railway to develop a country.”37

Even though rival U. S. interests owned the rail lines connecting Mexico City with the U. S. border, Limantour feared that cut-throat competition would lead to bankruptcy. That would hurt Mexico’s image and allow Mexico’s railroads to fall into the hands of unscrupulous foreign financiers. As a result, in a nationalistic move more commonly associated with post-revolutionary governments, the government began to purchase shares of foreign-owned rail companies. In 1908, the journal El Economista Mexicano observed, “If the state does not exercise control over the railroads, the railroads will exercise control over the state.” Due to the railroads’ financial weakness, it would have been easy for a single owner to take them over. Limantour’s fears were well founded, since rail monopolization had already resulted in ruinous rate increases in the United States.38

Limantour borrowed in France to obtain the funds he used to purchase rail shares. In 1908, he formed a government-owned rail company that controlled two-thirds of the nation’s rail system, including the all-important Central and National lines leading to the United States. The partnership of Scherer-Limantour Banking House purchased the shares and then sold them to the government at a profit. Limantour’s brother served as a partner in the firm and both the secretary and his brother were among the firm’s chief stockholders.39

The railroad had a profound social impact. In 1910, in a nation of 12 million, 15.8 million rail passengers were transported more than 1 billion kilometers. Many of these travelers used the railroad to relocate from central to northern Mexico. Travel time between Veracruz and Mexico City decreased from days to thirteen hours. A special train allowed Puebla residents to leave for Mexico City in the morning, shop or transact business in the capital, and return home for a late dinner.40

Only with the coming of the railroad did Mexico regain the degree of economic integration that it had enjoyed in 1800. Although railroads were largely foreign-built, they did link most inhabited regions, crossed the best agricultural districts, and reached the richest mineral deposits. The railroad’s linking of different areas not only allowed shipment of agricultural surplus from one area to another but also created a synergistic effect. New firms created new demand and new products. To supply railroad builders, Monterrey’s steel mills produced rails. In northern Mexico, coal mines supplied locomotive fuel, and ranches expanded so they could supply the U. S. market. As a result, between 1883 and 1911, rail freight increased at an average annual rate of more than 10 percent.41

The railroad facilitated the expansion of the mining industry. Without rail service it would not have been economically feasible to mine metals such as copper, zinc, and lead. Since the rail system linked most major urban areas and agricultural, mining, and industrial centers, it provided a powerful stimulus to the domestic economy. As a result, the railroad’s greatest impact was local. Between 1898 and 1905, less than 2.5 percent of total rail cargo went to the United States.42

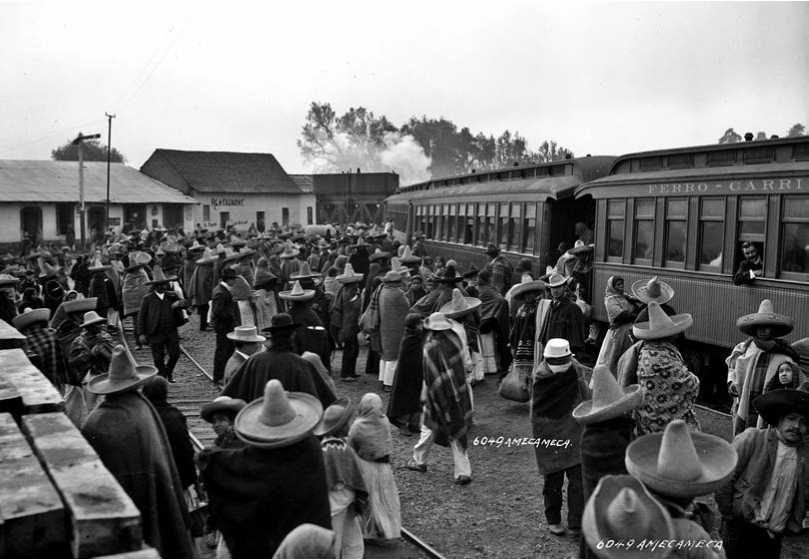

Figure 13.1 Native people leaving a train at Amecameca, Mexico, 1907, by Sumner Matteson Source: Reproduced courtesy of the Science Museum of Minnesota, photo #A 84: 16: 29

The railroad allowed cattle and crops, such as cotton, tobacco, and henequen, to be shipped to distant markets. It also allowed the development of previously underutilized regions. In 1884, Navojoa, in the agricultural heart of Sonora, had a population of 1,344. After the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad, its population jumped to 10,822, as growers began shipping their produce out by rail. In 1884, the Laguna region, on the Coahuila—Durango border, shipped less than 5,000 tons of cotton. In 1901, the railroad hauled more than 120,000 tons of cotton from there, mainly to mills in central Mexico.43

The impact of railroads rippled throughout the areas they served. Historian Allen Wells described the impact of the railroad on Yucatan:

Property values skyrocketed; large landholdings were concentrated near railway lines; imported goods—grains, manufactured wares, and luxury items—flooded local markets; and migration within the peninsula exploded as campesinos took advantage of the railroad to seek employment in the burgeoning state capital, Merida, and in the principal port, Progreso.44

The railroad would have had even greater economic impact if Mexican industry had been able to supply the construction material and rolling stock used. Mexico not only imported rail cars, locomotives, air brakes, and telegraph equipment but even rails and wood and coal for fuel. In 1910, 57 percent of gross railroad revenue left Mexico to pay for railroad equipment, consumer goods for railroad personnel, skilled foreign supervisors and engineers, profits, and interest on loans. Finally, rather than strengthening financial institutions as they did in the United States and Europe, railroad builders in Mexico largely ignored local banks and turned to foreign capital.45

Cities benefited from the railroad, as their residents could enjoy inexpensive agricultural goods produced in distant areas. Owners of large estates and factory producers also benefited as they could dominate large markets. Before the coming of the railroad, if agricultural capacity exceeded local needs, it could not be used. The United States also benefited, since the railroad shifted Mexico from a dependence on European goods to a dependence on U. S. goods. Innumerable other Mexicans benefited by being employed in endeavors that would not have existed without the railroad.46

Small farmers and artisans often suffered as the railroad led to ruinous competition with large-scale producers. Preferential shipping rates for exporters and high-volume shippers put the small producer at an even greater disadvantage. In the 1880s and 1890s, as marketing opportunities provided by the railroad led to an increase in cash crops, many subsistence farmers were forced off the land they had occupied. Some cities and regions lost out as trade patterns changed. Guaymas was displaced as the main supplier of imports to Sonora after rail lines connected the state to the United States via Nogales. In the 1870s, Tampico suffered economic collapse due to competition provided by the opening of the Veracruz—Mexico City line. In 1890, the city enjoyed an economic revival after rail service was established. This allowed the transshipment of European coal to foundries in Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosi, and Monterrey.47

Railroads consumed enormous amounts of wood for station construction, ties, bridges, posts, and fuel. An 1880 circular published by the Secretariat of Development reported that forest destruction had caused erosion, climate change, air pollution, increased flooding, the drying up of springs, and the loss of agricultural land.48

World History

World History