In the United States, the decades between 1810 and 1860 were a time of energy, invention, creativity, and accomplishment. It was also an exciting and inventive period for the arts, which reflected or reacted against remarkable changes happening in the nation. More than anything, American artists and architects of the antebellum period sought to free themselves from conventional and contemporary European dictates in taste and to establish their own uniquely American style of creativity.

If American culture was still rooted in a European heritage, there was nevertheless a unique quality about the land. Unlike Europe, the United States seemed to have unlimited land available to all citizens, regardless of class. A romance grew out of the land, out of Americans’ relationship to it, and out of their accomplishments on it.

In the East, Americans became nostalgic for a wilderness they knew they had lost to progress, as forests were cleared, factories rose, trestle bridges crossed rivers, and trains cut through the landscape. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny dictated that progress must take place across the land if America’s future were to be fulfilled, and in the 19th century, few who went west doubted the rightfulness of their mission. As early as 1804, the painter Washington Allston (1779-1843) grappled with the notion of breaking free from his traditional European training and exploring new tableaus. He sought to bridge the two prevailing schools of painting: traditionalism, in which nature and objects are faithfully and realistically reproduced, usually couched in some kind of moral message, and romanticism, an emerging approach that impelled artists to color their works by what they felt as well as what they beheld. Allston’s subsequent body of work represents the first American attempt to meld a universal moral message with the personal subjectivity of an artist. His work pleased homegrown critics and greatly influenced the next generation of painters.

From about 1825 Americans wanted images of the land itself: its mountains, forests, prairies; the lives and customs of the Native Americans who dwelt in it; the adventurous men and women who moved into and settled it. To some the landscape became a metaphor for moral, religious, and poetic sentiments, and so it must be preserved. To others it represented the American Dream because of the opportunities it offered, and so it must be utilized. Some saw interminable forests as a biblical Eden, awaiting a new Adam and Eve in the form of the American pioneers, who had a chance to regain grace in a land uncorrupted by the Industrial Revolution.

The patrons of these artists were often prosperous merchants, bankers, or factory owners, desiring scenes of natural splendor as an antidote to the harsh world of business; or rural scenes reminiscent of the days spent on the farm, when life was slower and easier—somehow better. Armchair travelers enjoyed paintings of the exotic West, which they might never see for themselves. To satisfy this

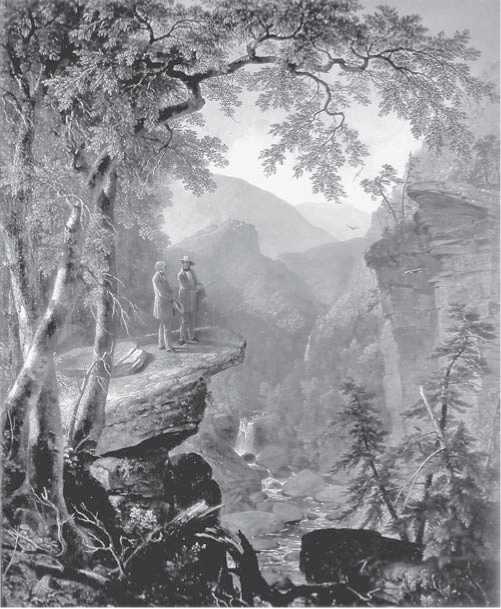

Kindred Spirits, painting by Asher B. Durand, 1849 (Library of Congress) demand, a large and talented corps of landscape artists emerged to paint essentially naturalistic visions altered by romantic sentiment. Landscape painting before 1825 had been sporadic, often quite good, but generally lacking a strong thematic focus. After 1825, it enjoyed a great flowering.

The initial impetus for an American school of art arose in the intense nationalism that followed the War of 1812, when a number of cultural institutions that were dedicated to cultivating a unique national aesthetic were established. The first such organization was the National Academy of Design, created in New York in 1826 by the painter Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872). Morse was one of a group of dissident artists who rebelled against the restrictive mores of the older American Academy of Fine Arts. The National Academy of Design was founded and run entirely by artists, and it limited exhibits to contemporary American painters, sculptors, and related artisans. Its success inspired Philadelphia’s Artist Fund Society in 1835 and New York’s American Art Union in 1838, both committed to showcasing American art exclusively. Within a decade the latter boasted 18,000 members and several thousand visitors in daily attendance.

The first American school of landscape painting was the Hudson River School. Many of these artists painted in and around the Hudson River Valley and the nearby Catskill and Adirondack Mountains. Beginning with the works of Thomas Cole (1801-48) and Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), the Hudson River painters helped to shape the mythos of the American landscape. At the time America was a nation yearning for artistic identity. The Hudson River style provided what Americans craved; dramatic and uniquely American landscapes. Artists, along with poets, novelists, and essayists, delighted in describing and depicting native scenery. Influenced by 17th-century European landscapes, the work of the Hudson River School is characterized by panoramic views rendered with precise detail. These serene and awe-inspiring vistas, in which a small figure often communes with nature, were intended to evoke elevated thoughts and feelings. With roots in European romanticism, the Hudson River painters, nonetheless, heeded Ralph Waldo Emerson’s call “to ignore the courtly Muses of Europe” and define a distinct vision for American art. The artists who came to maturity in the years of egalitarian Jacksonian democracy and expansion translated these ideals into an aesthetic that was sweeping and spontaneous. Sharing the philosophy of the American transcendentalists, the Hudson River painters created visual embodiments of the ideals set out in the writings of Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, William Cullen Bryant, and Walt Whitman. Concurring with Emerson, who had written in his 1841 essay, Thoagh-fs on Art, that painting should become a vehicle through which the universal mind could reach the mind of mankind, the Hudson River painters believed art to be an agent of moral and spiritual transformation. A painting that has become a virtual emblem of the Hudson River School is the dramatic canvas by Asher B. Durand entitled Kindred Spirits (1849). In it Durand depicts himself, together with Thomas Cole, on a rocky promontory in serene contemplation of the scene before them, the gorge with its running stream, the Catskill mists framed by foliage. Tiny as the human beings are in this composition, they are nevertheless elevated by the grandeur of the landscape in which they are in harmony.

But America’s fascination with landscapes was not solely confined to the eastern part of the nation. As America expanded beyond the Allegheny Mountains into the Great Plains, the arts soon followed. The frontier had its own chronicler in George Caleb Bingham (1811-79), who took his inspiration from the spirited life along the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers. Bingham’s work comes into historical focus with Fur Traders Descending the Missouri (ca. 1845). In the golden haze of a misty dawn, a French trader and his half-breed son move along the mirror-placid waters of the great river in a dugout canoe. They wear the typical colorful costumes of their culture, and have a wild-animal pet tied to the bow. Bingham saw something exciting and exotic in the men who lived in the solitary wilderness of the upper Missouri, running their traps or trading with Native Americans, and he captured the romance surrounding them. Pictures like this depicted a new type of folk hero, created by the land itself. Europe had no counterpart, and so here was a subject that was uniquely American.

Another significant school gaining popularity was genre painting, which, by 1840, proved equally as popular as landscapes and portraiture. Genre painting embraced the depiction of everyday life and activities by average, anonymous people. Farmers, frontiersmen, and riverboat men all figured prominently on the canvas, because in their simplicity and commonness they embodied the uniquely American sense of individualism and optimism about the future. Their usual placement in a frontier setting also celebrated both humans’ mastery of nature and a pristine, idealized concept of the West. The most important artist of this genre was John Lewis Krimmel, a native of Germany who immigrated to the United States in 1809 and settled in Philadelphia. Krimmel first worked for his brother, a merchant, but he soon left business to pursue a career as an artist. In the course of his significant but brief artistic life (he accidentally drowned in Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1821), he painted scenes from daily life, and he was probably the first American artist to do so. Among the paintings that he exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1813 were Quilting Frolic (a very American subject) and The Blind Fiddler (adapted from Sir David Wilkie’s English painting of the same name, but given an American identity). Krimmel was the first painter of American scenes (he never became an American citizen) whose reputation rested on his adaptation of contemporary American life as an appropriate subject for an American artist.

As some American artists pursued American subjects, African-American artists found themselves severely restricted in artistic life, as they were in all aspects of civil and professional life in the United States. While their chances of pursuing careers as artists were severely circumscribed, they did find opportunities for artistic expression in painting signs, firebuckets, and helmets.

Architecture

The period 1825-70 produced an architecture that can only be described as romantic and eclectic. Architects adapted Greek, Roman, Gothic, Oriental, and Egyptian styles to suit American ambition, ideology, or institutions, as well as nationalistic, religious, or moral sentiments. The range reached from austere classicism to picturesque Victorian “gingerbread.” New technologies and materials, such as cast iron, were forced into old forms, as in the classical dome of the enlarged U. S. Capitol. While popular in some circles, this eclectic style of architecture usually clashed with contemporary European practices. Neither approach fully excluded the other, and the debate they occasioned in architectural circles went unresolved. Curiously, devotees of the new national architecture were either self-taught or trained in Europe, as formal education in this discipline did not begin at home until after the Civil War.

The Greek Revival in America spanned the years 1820 to 1845. From the design of chairs to the style of women’s dresses, the Greek mode was enormously popular. Americans identified strongly with the Greek cause when in the 1820s Greece fought to free itself from the Ottoman Empire and Turkish despotism. The Greek War for Independence was associated with America’s own valiant struggle of a few decades earlier. Americans also recognized in Greece the cradle of democracy and the fountainhead of learning, culture, and the arts. To design a chair or a building in the Greek mode was to pay allegiance to the democratic spirit and to the timelessness of Western culture. For much of the mid-19th century, the Greek Revival style dominated residential and public architecture. Many European-trained architects designed in the popular Grecian style, and the fashion spread via carpenter’s guides and pattern books. It was so popular it became known as the National Style. William Strickland (1788-1854) contributed greatly to the rise of the Greek Revival style in America. Strickland was the designer of the Second Bank of the United States building in Philadelphia, which is a classic example of the American Greek Revival style. Strickland’s influence extended from his designs to his instruction of a new generation of young architects. Among those who studied with him was Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-1887). Born in Philadelphia, Walter made the transition to architect about 1830, after several years as an apprentice in the building trades and of study with Strickland. Among his most important buildings were Girard College (1833-47) and the extension of the U. S. Capitol (1851-59). The work over his long career eventually included some 400 designs, most of them classical residences and churches.

The model for Greek Revival architecture was the ancient Greek temple, in which a series of columns support a horizontal superstructure called an entablature and a triangular pediment. (The pediment of a temple is the narrow end of a gable roof forming a triangle, often filled with a decorative relief.) In the United States, the style was based on the Greek orders: sets of building elements determined by the type of columns that were used. The columns ranged from the simple Doric, with a fluted shaft; the Ionic, with a capital shaped like an inverted double scroll; and the Corinthian, with a capital shaped in an elaborate leaflike form. The shape of the building was rectangular, with columns placed in various ways. They could be at the front of the building, full height, down the side, or all around it, and frequently they were indicated by pilasters at the corners or elsewhere on the building.

Brick and stone were the favored materials, though wood was often used and covered with a thin coat of plaster, then scored to resemble stone. The doorway was usually impressive. Paired columns with a pediment over the door, transom lights, side lights, and pilasters against the wall were all used to embellish the entry. Windows were often floor-length, double - or triple-hung. There were also often small horizontal windows set in a row under the cornice and sometimes covered by a decorative wooden or iron grille. In the early to mid-1800s Greek temples appeared everywhere from Maine to Mississippi. Colonnaded Greek Revival mansions—sometimes called Southern Colonial houses—sprang up throughout the American South. With its classic clapboard exterior and bold, simple lines, Greek Revival architecture became the predominant housing style in the United States. The public proved entirely receptive to the style, so Greek Revival was applied to all manner of buildings, including banks, courthouses, city halls, and even farmhouses. Its widespread acceptance and application render it the first truly national architectural style.

The most enduring legacy of the Greek Revival style is the gable-front 19th-century farmhouse, often ornamented by only a flat pilaster doorway or corners. Usually called the New England Farmhouse, this became a popular form for detached urban houses in cities of the Northeast until well into the 20th century. In rural areas, the form of Greek Revival known as gable-front and wing (called, similarly, New England Farm) remained a popular form for farmhouses until the 1930s.

During the second half of the 19th century, Gothic Revival and Italianate styles captured the American imagination, and Grecian ideas faded from popularity. Most American Gothic Revival houses were built between 1840 and 1870. The Gothic Revival began in England and became the dominant style for country houses there. After it became accepted for English church building, it was promoted as the popular style for all English buildings from 1840 to 1870. In contrast to the ordered symmetry of Greek Revival, churches constructed as Gothic Revival were decidedly upswept and asymmetrical, with high pointed arches, steeples, and pinnacles much like their Medieval progenitors. Americans also liked this form, but only as one of several romantic styles to be modeled to Victorian American tastes.

The most important architect associated with the Gothic Revival style was Richard Upjohn. Born in England in 1802, in 1829 he immigrated to the United States, where he first worked in the building trades and, beginning in 1833, advertised himself as an architect. Among his first commissions were requests from the city of Boston to design street lamps and cast-iron fences and gates for the Boston Common. Upjohn’s first important work was Trinity Church in New York City, which was a landmark Gothic Revival style and established Upjohn as one of the leading architects in the nation. Over the next 20 years, Upjohn designed a score of major churches and numerous minor ones, and in addition, he extended the Gothic style to domestic buildings. In 1852 he published Upjohn’s Rural Architecture, in which he laid out a wide range of plans from cottages to churches for individuals and congregations unable to afford his personal services. Upjohn’s eldest son, Richard Mitchell Upjohn, joined the firm in 1846, and in the 1860s the elder Upjohn gradually retired in favor of his son.

As a result of the economic opportunities of the Industrial Revolution, the growing middle class had more money to spend on housing and wanted to build attractive homes outside the cities in healthy surroundings. Horse-drawn railcars brought the man of the house to and from work, gas lights and indoor plumbing were becoming available, and all sorts of new devices and household machines (including iron cook stoves) were being invented. With these developments, the Gothic Revival bloomed. Perhaps the style achieved its greatest and most famous expression in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, which was designed by James Renwick (1818-95) and constructed from 1858 to 1879. The Gothic Revival style briefly faced competition from the more ornate Romanesque Revival style of the 1840s. The Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C., also designed by Renwick, is a prime example of Romanesque Revival architecture.

Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-92) was the first American architect to champion Gothic domestic buildings. Works by him include the New York Customs House (1832), now the Subtreasury; the state capitols of Indiana (1832-35), North Carolina (1831), Illinois (1837), and Ohio (1839); and a number of villas along the Hudson River, including Lyndhurst (1838-42).

But it was Davis’s friend Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52) who expanded the Gothic Revival movement with pattern books and tireless public speaking about the virtues of the style. Previous publications had shown details, parts, pieces and occasional elevations of houses, but Downing’s book Cottage Residences (1842), was the first to show three-dimensional views complete with floor plans. The Gothic Style fed public fascination with the romance of the medieval past. Downing’s books—including Architecture for Country Houses (1850)—offered not only designs for houses but also site and landscape plans to ensure a “happy union.” Downing is considered the founder of landscape gardening in this country. While Frederick Law Olmstead (1822-1903) dealt with the grander landscapes on a larger scale, Downing dealt more with American middle-class homes and emphasized gardening and plants, as he was also a nurseryman. Like those of Olmstead, his landscapes were influenced by the English style and were natural in appearance, as he described in his book The Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841).

Further reading: Catherine W. Bishir, Southern Built: American Architecture, Regional Practice (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006); Michael W. Fazio, The Domestic Architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006); J. Ritchie Garrison, Two Carpenters: Architecture and Building in Early New England, 1799-1859 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006); Calder Loth, The Only Proper Style: Gothic Architecture in America (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975); Judith K. Major, To Live in the New World: A. J. Downing and American Landscape Gardening (Cambridge, Mass., and London The MIT Press, 1997); David Schuyler, Apostle of Taste Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815-1852 (Baltimore, Md. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996); Robert Kent Sutton, Americans Interpret the Parthenon: The Progression of Greek Revival Architecture from the East Coast to Oregon, 1800-1860 (Niwot, Colo.: University Press of Colorado, 1992); Catherine H. Voorsanger, and John K. Howat, Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825-1861 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000).

Ashley, William Henry (1778-1838) American fur trader, soldier, politician

Born in Chesterfield County, Virginia, in 1778, William Henry Ashley moved to Missouri in 1803, soon after the Louisiana Purchase had taken place. Over the next generation, he was a fur trader, land speculator, and politician. As a fur trade entrepreneur, Ashley outfitted expeditions that covered much of the Rocky Mountains and plateaus of the West. Ashley also organized the brigade system of trapping, including the annual RENDEZVOUS that would become associated with the emergence of free trappers and MOUNTAIN MEN as features of the American fur trade.

After Ashley settled in Missouri in 1803, he manufactured gunpowder and lead, items that became enormously profitable during the War Of 1812. As a result, when the war ended, he was a wealthy man. Ashley was also a prominent figure in the territorial (and later state) militia, where he was elected lieutenant colonel during the war and later rose to the rank of brigadier general. He would later use this title to enhance his political career, and when Missouri entered the Union in 1821, he was elected lieutenant governor.

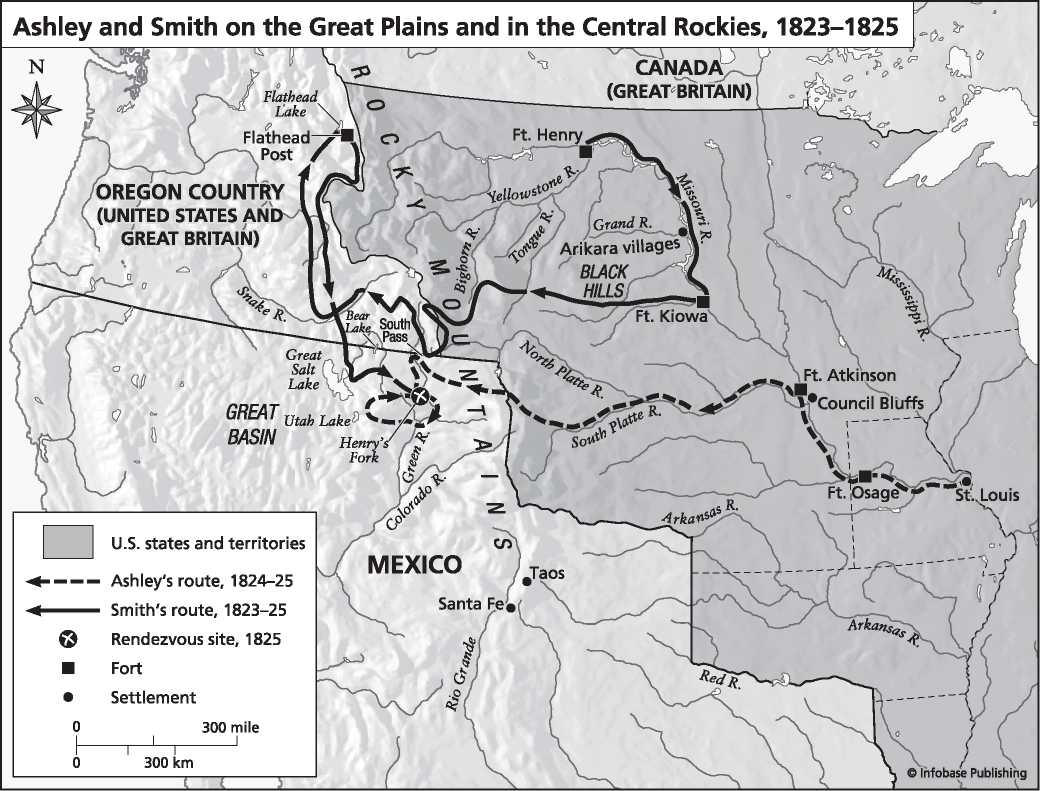

Like many others, Ashley’s economic circumstances suffered in the PANIC Of 1819, and he sought opportunities to recoup his losses. Even as he served his state in its second highest office, he remained active in fur-trade ventures. In 1822 Ashley and Andrew Henry advertised in the Missouri Gazette for “enterprising young men” to undertake an expedition into the upper Missouri. When eventually formed, the expedition was financed by Ashley and led by Jedediah Strong Smith. Although the party of veteran fur traders penetrated as far as the Missouri’s junction with the Yellowstone River, where they established Fort Henry, the opposition of the Arikara Indians was too strong. A second expedition the following year was ambushed by the Arikara, with the loss of a dozen trappers.

Concluding that the Missouri was too dangerous, Ashley sought other routes to the fur sources of the Rocky Mountains. His solution was to dispatch parties on horseback overland to the Rockies; these groups of trappers were called “brigades.” One of the first overland parties, under Henry, traveled across Nebraska to reach Fort Henry on the Yellowstone. Another, under Jedediah Smith, went by way of the Black Hills to the Wind River Mountains. In early 1824 Smith’s party discovered South Pass (previously discovered by Robert Stuart in 1812), which was to become a key route through the Rockies on the overland trail to California and Oregon. Ashley soon followed Smith to the rich, fur-bearing streams of the Green River Valley. He subsequently redirected the fur trade away from Canada and his main rival, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and into the southern areas of the Louisiana Territory.

In autumn 1824 Ashley started out from St. Louis with supplies for the trappers who were to remain in the mountains for the winter. His pack trains succeeded in making their way through the winter snows. In April 1825 his trappers dispersed to travel and trap in small groups, agreeing to meet on the Green River in the summer of 1825 (at the close of the trapping season). The first celebrated rendezvous was held near Henry’s Fort on the Green River. It was to be followed by a series of annual rendezvous, in which trappers would convene at an agreed site to drink, gamble, fight, and generally make merry, and to trade their furs for Ashley’s supplies. Ashley then brought the furs out of the mountains by pack train. The annual rendezvous continued in the Rockies until 1840. Ashley was present at the first two but after the second, in 1826, he sold his business for $16,000 to Jedediah Smith, David E. Jackson, and the William L. Sublette Company. This company was, in turn, succeeded in 1830 by the RocKY Mountain Fur Company. Although he had left the business and no longer par

Ticipated in the annual rendezvous, Ashley remained active in the fur trade by handling financial matters for various St. Louis companies.

Ashley’s strategies changed the direction of the fur trade. Previously, trappers had been forced to sign on for service in large companies, for only such an arrangement could provide supplies on credit and physical safety in numbers during the trapping season. In return, the trappers agreed to sell their furs to the company at a specified price. Amidst this large-scale organization, so-called free trappers or free traders were rare. Ashley revived the free trappers by giving them a support and safety system in the form of brigades and supplies provided in the field. Aside from the high degree of business acumen he displayed, Ashley also understood the demands of the trappers from personal experience. His presence on the expeditions and at the first two rendezvous made him not only a planner but also a participant. Furthermore, in addition to his use of free trappers in brigades and horses as transportation, his system supported St. Louis in its continuing connection to the fur trade, bounded on one side by the Hudson’s Bay Company and on the other by the financial colossus of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. Ashley’s personal bravery and ingenious business strategies for putting men in the field and supplying them made St. Louis an important city in the fur trade. Ashley himself was one of the first St. Louis-based businessmen (as opposed to Astor in New York) to make a fortune in furs.

Upon his retirement from the fur trade, the wealthy Ashley settled in St. Louis, where he pursued other trading and banking interests as well as politics. In his revived political career, he had the misfortune to be a dedicated member of the Whig Party at a time when the Jacksonian Democrats had a large majority following in the state of Missouri. As a man of strong principles, Ashley refused to change his political allegiance, and he continued to campaign as a Whig throughout the next decade. As a result he failed in his campaigns for governor and senator, although he was elected to Congress for three terms, serving from 1831 to 1837. In the House of Representatives, he devoted himself to what he regarded as western interests, especially western expansion and the fur trade. Ashley also ran unsuccessfully for governor twice. He intended to run for Congress again when he was suddenly taken ill and died in 1838.

Although he was slight of stature, Ashley was acknowledged by those in the fur trade as brave and daring. He was also a natural leader in the field, perhaps reflecting his service in the militia. His business methods were enormously creative in an enterprise that had become increasingly the monopoly of two large groups, the Hudson’s Bay Company and Astor’s American Fur Company. Through such innovations as the trapping brigade and rendezvous, Ashley made St. Louis an important city in the fur trade. Furthermore, the geographic discoveries of those trappers in his employ would be significant in subsequent expansion across the continent.

Further reading: Richard M. Clokey, William H. Ashley (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968); Dale L. Morgan, The West of William H. Ashley (Denver, Colo.: Old West Publishing Company, 1964).

Astor, John Jacob (1763-1848) fur trader, merchant, entrepreneur

The son of a poor butcher in Waldorf, Germany, John Jacob Astor was born on July 17, 1763. He would become America’s most notable fur trade entrepreneur, and at his death, its wealthiest citizen. Astor’s early life paralleled noteworthy changes in the continent of North America that would directly influence his career. Born at the close of the

French and Indian War, in 1780 he immigrated to Great Britain, where he joined his brother George. He worked for his brother for three years, during which he learned English and saved his money for emigration to the United States.

Astor crossed the Atlantic in 1783, the same year that the Treaty of Paris confirmed America’s independence. Because his vessel remained icebound in Chesapeake Bay for two months, it was not until March 1784 that Astor reached New York City, where he joined his brother Henry. Although he brought with him a modest capital in flutes, Astor’s future was not in musical instruments but in the fur trade. He soon found a position in a fur store in New York City, where for two years he learned how to purchase furs in upper New York State and ship them through New York City to London. It was a lucrative business, and within two years, Astor had set up his own business.

After Jay’s Treaty (1794) forced the British evacuation of the frontier posts in the Northwest Territory and reduced tensions and trade restrictions between the United States and Canada, Astor began to trade with the North West Company in Montreal. His business prospered, profiting from his astute negotiations with suppliers and his knowledge of the fur business in New York City. By 1800 he had amassed a fortune of $250,000, making him the leading fur entrepreneur in America. It was about this time that Astor began to ship furs to China; the first trading voyage to Canton netted him $50,000. He also made his first large purchase of New York real estate when in 1803 he bought 70 acres at the northern edge of the city, a tract that would become the heart of one of his several fortunes.

After President Thomas Jefferson acquired the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, he dispatched Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the region. Astor immediately recognized the significance of both the purchase and the expedition for the fur trade. Lewis and Clark crossed the continent to the Pacific Coast (1804-06) through some of the richest fur-bearing landscape on the continent, and Astor fully intended to exploit their discoveries. In 1808 he founded the American Fur Company as a corporation chartered by the state of New York for $2 million; Astor owned all the stock. At this time, the fur companies of St. Louis (the largest in the West) were each capitalized at less than $25,000.

Astor’s strategy, as it developed over years, was to establish a post at the mouth of the Columbia River, from which his employees would trade with Indian peoples throughout the reach of the Columbia and its tributaries. Astor’s ship would then carry the furs gathered at the mouth of the Columbia to Canton, where they would be sold to Chinese merchants. The goods acquired there would be traded in Europe, and eventually the profits would accrue to Astor in New York City. Astor calculated that on an annual basis, a single supply vessel would be sufficient to support the operation in the Pacific Northwest. In 1810 he organized the Pacific Fur Company—a direct competitor of the North West Company (Montreal) and the Hudson’s Bay Company (London)—and recruited and dispatched two expeditions to the Pacific Coast. His employees founded AsTORlA at the mouth of the Columbia River in the spring of 1811, acquiring a key location in the fur trade for transshipping furs to Canton, and providing testimony to the capital that Astor was willing to invest. His triumph was brief. News of the declaration of war with Great Britain reached Astoria in January 1813. In autumn of that year, Duncan McDougall, head of Astor’s operations, sold the fort and the surrounding tract of land to representatives of the North West Company for $58,000. This sum represented only a fraction of Astor’s investment. Within little more than a month, a British warship arrived at the mouth of the Columbia, and on December 12, 1813,

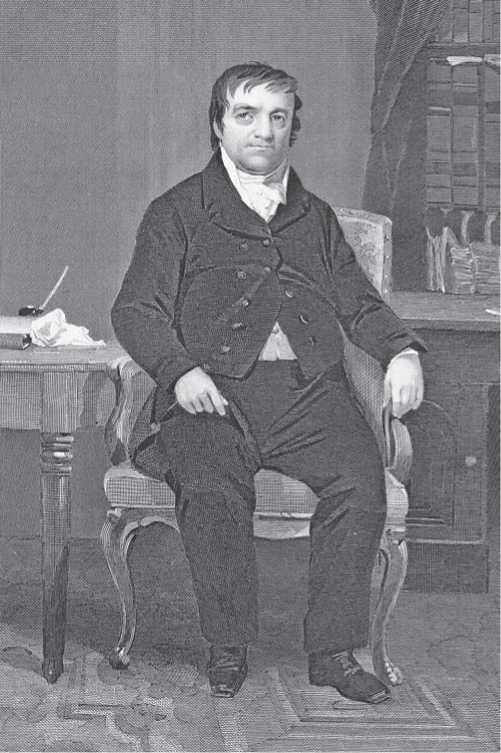

John Jacob Astor (Hulton/Archive)

Its captain took possession of the region and renamed the post Fort George, to honor the British monarch.

Although Astoria was a severe financial loss, in other respects Astor found the war very profitable. His Manhattan real estate holdings rose in value throughout the conflict. He also profited enormously from a large loan to the federal government. By 1814 the American government was in a desperate financial situation. The War OF 1812 had been fought on credit, and in the face of military reverses, finances had become tight. Along with two Philadelphia bankers, Astor bought a large block of loan bonds from the government at 80 cents on the dollar. He then paid for the bonds with notes worth approximately half their face value. The war ended in less than a year, and Astor made a fortune from the government bonds. Although he always thought of himself as a patriotic citizen, he considered the war another of a series of business transactions, and he saw no reason not to take advantage of generous terms.

At the close of the war, Astor turned once again to the fur trade. The Treaty Of Ghent, signed in 1814, specified that territory seized during the war should be returned. As a result, Astor sued for the return of Astoria, but the British government argued that Astoria had been sold, not seized. In a technical sense, this was true, but Astor was able to show that the purchase price represented only a fraction of his investment. His case won, Astoria was once again in his hands.

When Astor had lost the outpost in the Pacific Northwest, he had also lost a considerable investment with it. No other entrepreneur associated with the fur trade could have absorbed such losses and remained in business. Whatever the size of Astor’s operations—and they were huge—his company was an American concern at a time when the major competitors were British or Canadian. Thus, American officials at many levels applauded his aggressive plans as something that served the national interest. In 1816, at his urging, Congress passed a law that excluded foreigners from engaging in fur trading on American soil except as employees.

Astor also used his immense political power to force the U. S. government out of the fur-trade business. Under legislation passed in 1795, Congress had created a factory system through which the federal government established factories, or trading posts, to serve as a model of honest and ethical practices with Indian peoples. These government posts would offer high-quality goods at reasonable prices but without alcohol. However idealistic the concept, Indians continued to trade at the private posts, preferring traders as friends to doing business with government employees. Astor resented the federal competition, however mild. In 1822 Congress succumbed to the powerful political influence of the private American fur-trading companies and Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, the representative of fur interests in the Senate. Consequently, the private companies, reduced in number by fusion (including the melding of the North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company by Act of Parliament in 1821) but strong in influence, had the field to themselves.

After the War of 1812, Astor extended his trading operations to control the fur trade from the Great Lakes to the Ohio River. He established a key post at Mackinac, through which he expanding his trading operations into the upper reaches of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. To pursue this end, in 1822 he established the western department of the American Fur Company, In so doing, he gained a virtual monopoly of the fur trade in the upper Missouri country, and his operations bankrupted many small traders.

For years, Astor was hated and feared by the St. Louis fur-trade interests, which were much smaller operations. Although one of Astor’s great skills as an entrepreneur was reaching an accommodation with the competition, he was never able to do so with the traders in St. Louis. Astoria and his plans for the Pacific Northwest bypassed these competitors, but his expanded operations in the 1820s brought him increasingly into direct competition with the St. Louis companies. He mounted a direct challenge to the RoCKY Mountain Fur Company that was characterized by his usual daring and resourceful campaign, but his efforts failed. The returns were lower than expected, and conflicts with the Indians (especially the Blackfeet) resulted in serious losses. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company was composed of some of the best trappers and traders in the history of the fur trade—the Sublette brothers, Thomas Fitzpatrick, and Jim Bridger—but these were men at home in the mountains and around the lodge fires, not in the counting house. Although they managed to hold Astor at bay, their triumph was a short one. Fashion was changing, and the fur business was in decline. In June 1834 Astor sold his fur business. It marked the close of an era in the American West.

Astor spent his remaining years in New York City. His astute investments in real estate—financed by profits from the fur trade—had made him the wealthiest man in America. More than any other individual, including William Henry Ashley, Astor turned the fur trade into a profitable business. In order to survive against the rival North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, he created a series of large companies. That he succeeded was testimony to his remarkable acumen in corporate organization and in shrewdly assessing the rise and decline of the fur business. He died at his home in New York City in 1848, leaving an estate in excess of $40 million.

Further reading: John Denis Haeger, John Jacob A. stor: Business and Finance in the Early Republic (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1992); David Lavender, The Fist in the Wilderness (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1964).

World History

World History