As the Depression settled in, late in 1929, Mackenzie King’s Liberals appeared to have a firm hold on office. Neither the Government nor the Conservative Opposition, led by R. B. Bennett, believed that the economic downturn called for any unusual measures. Both proposed tariff changes. In keeping with their traditions, the Liberals

Proposed tariff adjustments designed to reduce duties on a few items while raising them on others. Beyond that Charles Dunning, the Minister of Finance, budgeted for a surplus. The provinces were left to deal with the social problems created by the economic collapse. Bennett, also in keeping with his party’s traditions, argued that higher levels of protection were needed to preserve the Canadian market for Canadians until other countries, notably the United States, lowered their tariffs.

King thought that the tariff issue was a good one on which to face the country. The election of 1930 was fought largely on the tariff, though King’s ill-considered remark that his government would not give five cents to a provincial Conservative administration was effectively used by the Opposition. R. B. Bennett, to the astonishment of most Canadians, emerged from the election as the clear victor.

The new Conservative Prime Minister, a New Brunswicker who had made his fortune as a corporation lawyer in western Canada, was a man of enormous energy. A large, stern, Methodist bachelor, Bennett had little ability to delegate authority and slight respect for those who dissented from his views. Though a kindly and charitable man in private life—he often sent personal donations to those who appealed directly to him—he had the self-made man’s attitude to social distress: self-help was better than public assistance. Flis roaring denunciations of real and imagined radicals soon earned him the dislike of those Canadians who needed more than sermons to deal with their distress. Bennett’s wing collar and top hat, together with his ample form, came to symbolize the bloated capitalist in many a caricature.

During the first four years of his term, Bennett sought to restore prosperity with traditional economic policies. Fie raised the tariff to an unprecedented level, claiming that this was a necessary step in “blasting” open the markets of the world. Then, in 1932, an Imperial Economic Conference was called at his suggestion in Ottawa. He hoped that Britain and the dominions would agree to the establishment of an imperial free trading area, protected against the rest of the world. Britain, in particular, had trading interests that reached far beyond the Empire, and found this proposal quite unacceptable and Bennett’s bluster offensive. Though some tariff changes were accepted, the conference was largely a failure, especially since it contributed to the protectionist trends that were strangling international trade. As the Depression deepened, Bennett, without departing from his free-enterprise view of the role of government in the economy, did increase payments to the provinces for the relief of unemployment. So, too, his government sponsored legislation establishing the Bank of Canada, adding an important weapon to the central government’s fiscal and mon-

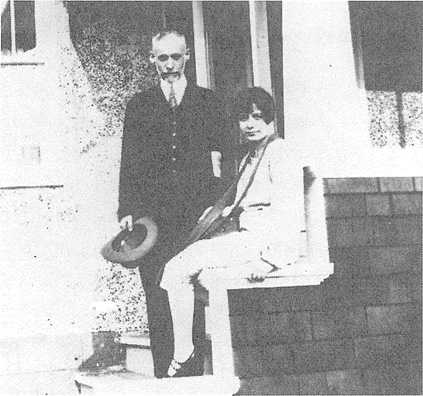

J. S. Woodsworth, posing with his daughter at their Winnipeg home. In 1904, Woodsworth moved from the regular Methodist ministry to social work among western Canada’s new immigrants and the poor. An adamant pacifist and labour supporter, he was the first leader of the CCF.

Etary arsenal. The work camps in British Columbia were a further attempt by the Conservatives to

Deal with unemployment. But by 1934, with growing unrest in the country, evidence of the government’s declining popularity, and no sign that the Depression was lifting, Bennett was forced to begin rethinking his approach to economic and social policy.

Discontent with the Bennett government took a variety of forms. One, very close to home, was an attack on the spread between wholesale prices charged to large and small firms, which led to huge profits for some large companies and serious hardship for many small businesses. That attack was led by H. H. Stevens, a member of Bennett’s own cabinet. In 1934 Stevens was made chairman of a royal commission authorized to investigate the price-spread issue. Much of the evidence it heard was damaging to the country’s leading retailers and manufacturers. Stevens soon became recklessly outspoken in his criticisms of these firms. An angry Prime Minister forced his resignation from Cabinet in response to pressure from businessmen. This was only one sign of the growing disarray of the Conservative party, which was already evident from a series of party defeats at the provincial level.

Then there was the emergence of new, unorthodox political movements. One was the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, soon known as the CCF. Founded at Calgary in 1932, this coalition of farmers, labour leaders, and intellectuals provided itself with an ominous-sounding program the following year. The “Regina Manifesto,” prepared by a group of radical university professors, called for the implementation of a number of measures that would make government responsible for social and economic planning. It promised unemployment and health insurance, public housing, agricultural price supports, and laws to protect farmers against their creditors. But the new party’s socialism was most clearly revealed in its advocacy of public ownership of leading industries and financial institutions. As its first leader the party chose the veteran radical and parliamentarian J. S. Woodsworth, who, since 1921, had been the member for Winnipeg North. The party’s founders hoped to build widespread popular support by affiliating with farm and labour groups, but the latter proved very cautious. The beginnings were solid, but growth proved slow.

The mushroom growth of the Social Credit movement provided a startling contrast. Unlike the ccf, which had support in both central Canada and the West, Social Credifs origins were entirely western, almost entirely Albertan. The doctrine itself had been devised by an English engineer. Major C. H. Douglas, who argued that economic depressions did not result from over-production, but rather from underconsumption—the result of currency and credit shortages. That deficiency could be overcome by issuing a “social dividend” which, by increasing purchasing power, would lead to economic revival. Such an inflationary doctrine had a natural attraction for farmers, whose heavy debt load convinced them of the need for an increase in the money supply. In the early thirties Social Credit ideas began to circulate among members of the United Farmers of Alberta, but their political leaders, who had held office since 1921, remained faithful to the same monetary orthodoxy as the old parties.

What the UFA government rejected was accepted by the Calgary schoolteacher turned radio evangelist, William Aberhart. Since the early thirties, “Bible Bill” Aberhart had been using the new technology of radio to broadcast his fundamentalist Protestant message to a widening circle of prairie listeners. The misery the Depression created around him, especially the plight of his unemployed high-school graduates, turned his mind to social and economic questions. The essential simplicity of Social Credit economics appeared to offer a solution almost as apocalyptic as his biblical messages. His Sunday broadcasts soon began to mix religion with economics, something that social-gospel ministers had been doing for decades on the prairies. By 1935 the UFA government found itself facing a growing popular movement led by a political neophyte, who himself refused to run for the legislature, claiming his ideas were non-partisan. In the provincial election of that year, Aberhart’s followers triumphed easily on the promise to abolish poverty in the midst of plenty by the application of Social Credit policies. Aberhart was called upon to form a government, and he later won a seat in the legislature in a by-election.

Once in office, the new premier found it difficult to transform the generalities of his message into concrete measures. Not the least of his problems was the constitutional one: the federal government controlled the fiscal and monetary powers that Would be necessary to implement Social Credit ideas. At first Aberhart temporized. Then he had several measures enacted providing for a social dividend, restricting banking activities and debt collection, and regulating the press. Nearly all these measures were found unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1938. Aberhart now urged Social Creditors to work to win office in Ottawa, while he set about providing honest, efficient, and generally rather conservative government in Alberta. With the discovery of rich petroleum deposits at Leduc in the 1940s, Albertans were provided with a social dividend that promised even greater abundance than Major Douglas’s doctrine—and one that Aberhart’s successors found much easier to administer.

Finally, there was the emergence of a new political party in Quebec. The Union Nationale was a coalition of Conservatives and a number of young Liberals who were disenchanted with the conservatism of the Taschereau Liberals. Maurice Duplessis, a long-time Conservative, was an effective organizer and orator. The young Liberals, calling themselves L’Action Liberale Nationale, provided a program that was at once progressive and nationalist, focusing on the needs of urban dwellers and calling for provincial control of the electricity “trust.” Duplessis chose instead to concentrate on the evidence of extensive corruption in the forty-year-old Liberal administration. His effective use of this evidence, combined with the discontent created by the economic crisis, brought Duplessis and his coalition to power in 1936. He rapidly clipped the wings of his reformist allies, introduced a series of measures which assisted hard-pressed farmers, and consolidated his political base. He ingratiated himself with Catholic church authorities by enacting a “Padlock Law” that allowed him to close buildings that he judged were being used for “subversive” activities. He won the support of nationalists by loudly defending Quebec’s autonomy against real

During the Depression, Alberta preacher-evangelist William Aberhart denounced the “Fifty Big Shots” who controlled the banking system; his Social Credit government promised every adult Albertan a $25-a-month “social dividend.” The Social Crediters swept to power in 1935.

And imagined federal infringements. His Union Nationale party had become conservative in everything but name.

By 1935, the irrefutable evidence that the Depression was not going to disappear, combined with the declining fortunes of the federal Conservatives, convinced Prime Minister Bennett of the need for a dramatic new departure. His model was Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Without consulting his Cabinet, the Prime Minister took to the air waves and in a series of addresses set out the general lines of his own “new deal.” These reform measures, he claimed, were the necessary response to the “crash and thunder of toppling capitalism.” His Cabinet, the Opposition parties, and the Canadian people were astounded at this conversion, one which many suspected had taken place at the death bed. Bennett now met Parliament and presented his hurriedly prepared legislation. It provided for unemployment insurance, minimum wages and maximum hours of work, and new fair-trade-practices legislation, and established a grain board to regulate wheat prices. These proposals met with little opposition from the other political parties, whose members were anxious to get on with the inevitable election. But the 1935 election revealed that Bennett’s eleventh-hour reforms had been too late. The government was roundly defeated. The Liberals were re-elected with a comfortable majority, but the popular vote told a different story. The Liberals gained no larger a percentage of the vote in this victory than they had had in the 1930 defeat. Voters who deserted Bennett went, for the most part, to the new parties, as Social Credit, CCF, and even H. H. Stevens’ Reconstruction party all gained seats. Though King was the official winner, his Liberal party was obviously on probation.

The new King government offered little to those who had voted for change. Bennett’s “new deal” legislation was referred to the Supreme Court, which found its most important provisions unconstitutional. No new social policy initiatives were taken. A trade agreement with the United States, the negotiation of which had been begun by the Conservatives, was ratified. Beyond that the government seemed almost completely unwilling to challenge the bonds of fiscal orthodoxy or constitutional restraint. It was virtually helpless as a result. But as the economy again dipped in 1937, and the extent of personal suffering and institutional bankruptcy spread. King concluded that at least the appearance of action was necessary. He appointed a royal commission.

The Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations, or the Rowell-Sirois Commission as it was best known, had a mandate to examine the distribution of constitutional powers and the financial arrangements of the federal system. Judicial decisions since the 1920s had left the provinces with heavy responsibilities in social fields And the federal government with access to the largest sources of revenue. The commission’s task was to find a new constitutional equilibrium that would distribute revenues and responsibilities in conformity with the needs of an industrial society. Its work was not welcomed everywhere: premiers Hepburn, Duplessis, and Aberhart were loud in their opposition, while other provincial premiers worried about the potential centralist thrust of the commission. In 1940, its major recommendations, which included federal responsibility for unemployment insurance and the establishment of a system of federal adjustment grants to the provinces, were rejected by the largest provinces, led by Ontario. But by that date the outbreak of another world war made a rearrangement of federal-provincial revenue sharing a necessity, at least on an ad hoc basis. Moreover, by then King had won the approval of the provinces for a constitutional amendment giving Ottawa the power to enact unemployment-insurance legislation.

The King government also moved cautiously towards a more interventionist approach to economic management. Leading members of the public service—O. D. Skelton, Clifford Clark, and some younger Liberals—insisted that the countercyclical doctrines of the British economist John Maynard Keynes were practical. That meant that the time-honoured goal of the balanced budget had to be jettisoned and deficit financing accepted as a means of “priming the pump.” If consumer purchasing power was increased, the demand for goods and services would get the unemployed back to work. By 1938 the federal government was financing a variety of work projects, supporting a costly youth-training program, and contributing substantial subsidies to house building and other construction projects.

“In these days,” the recently converted Minister of Finance stated in 1939, “if the

People as a whole, and business in particular, will not spend, government must____

The old days of complete laissez-faire, and the-devil-take-the-hindmost, have gone for ever.” Within months renewed world war brought unprecedented increases in government activities and expenditures. With it came an end to the years of deprivation, unemployment, and human despair.

World History

World History