11.1 INTRODUCTION

Archaeology has a long history when compared to anthropology. Whether one chooses to look to the Renaissance as a starting point for the discipline’s development or the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries matters less than understanding that it is a history punctuated by periods of significant change and debate (Trigger 2006). We find ourselves in the midst of one of the more significant periods in the field’s history. Chief among the elements shaping our present moment are the growing voices of indigenous peoples around the globe who find their history the subject of our enquiries. In North, Central, and South America, Australia, and New Zealand, the growth of indigenous archaeologies has resulted in a greater degree of collaboration between archaeologists and indigenous populations (e. g., Atalay 2006; Echo-Hawk and Zimmerman 2006; Ferguson 2003, 2004; Lilley 2006; Lydon 2006; Nicholas 2010; Peck et al. 2003; Silliman 2008; C. Smith and Jackson 2006; L. Smith 2000, 2001; L. Smith et al. 2003; Watkins 2005). In Africa where the influence of postcolonial theory has raised important questions concerning identity politics and heritage, the demarcation between indigene and nonindigene remains contested (Segobye 2009). Similar issues concerning the history and identity of indigenous peoples in the New World point to the complexity of the issues confronting archaeologists today. Yet despite these complexities, the questions being raised by indigenous scholars have presented a challenge to archaeologists concerning the questions we often ask, the nature of the evidence we deploy, the language we employ in our discourse, the manner in which history is produced, and, perhaps most importantly, the way we categorize time (e. g., Atalay 2006; Schmidt

And Walz 2007a, 2007b; Watkins 2005; Gould, Rizvi, this volume). Each of these topics deserves serious discussion, but here I examine the manner in which time is conceptualized.

My interest in concepts of time stems from research focusing on the integral part it played in the growth of industrial capitalism. The spectre of the clock tower in nineteenth-century factory yards across Britain, Europe, and the United States was part of a labour regime that sought hegemonic control over its workforce (Mrozowski 2006). During this same period the growth of more abstract forms of temporal measurement would influence the development of the concept of prehistory as something separate and different from history. These notions of time stand in fairly stark contrast to the more deeply mythologized, but no less historicized temporal perspectives I would discover working collaboratively over the last decade with Rae Gould (this volume) and the Tribal Council of the Nipmuc Nation. This involvement increased my awareness of issues raised by a growing number of Native American scholars concerning archaeological research, including how they conceptualize time and the role these notions play in how they represent their own histories (e. g., Echo-Hawk 2000). A consistent feature of Native American conceptions of time is the absence of prehistory (e. g. Googoo et al. 2008).

So, one problem I have with the concept of prehistory is pragmatic: if I want to continue working collaboratively with Native American groups, then I must respect their beliefs that the concept is offensive because it relegates their history before the arrival of Europeans in the New World to a time before history begins. Thus, prehistory may be viewed as a tyranny because it imposes a barrier to both collaborative research and the search for a deeper history. First and foremost, collaborative research is based on mutual respect (Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson 2008; Kuwanwisiwma 2008; Nicholas 2010; Silliman 2008). Therefore, to accept the notion that the history of a people is to be artificially divided is to end your collaboration. In the spirit of full disclosure, no member of the Nipmuc Tribal Council or any Native American scholar with whom I have worked has ever voiced disdain for the term ‘prehistory’ unless I asked them directly.

In practice the concept of prehistory has, and continues to present, a barrier to drawing connections between the present, the recent past, and a deeper past. In truth no such barrier should exist; yet one is manifest in the scholarly divide between historical archaeology and prehistory. Prehistoric archaeologists seldom attempt to link their research to contemporary issues in the same way that historical archaeologists do, especially those working in areas of the world that have been subject to European colonization. By the same token, historical archaeologists seldom try to push their research deeper into the past, with the notable exception of African archaeologists who regularly tack between the deep past and present (Lane, Palowicz and LaViolette, Schmidt, Walz, this volume). As Schmidt (this volume) notes, an historical archaeology that focuses solely on societies that have entered the sphere of European colonization and industrialization is equally biased. Lightfoot (1995) was one of the first to raise this point when he asked who would be best suited to carry out the archaeology of the pluralistic societies that were emerging as a result of colonialism. These questions remain and very probably will until the value of connecting recent and deeper histories is demonstrated.

Some of the reasons for drawing connections between the present, recent, and deeper pasts are indeed political. In the United States, for example, the federal recognition process relies exclusively on written forms of documentation. This leaves no place for either oral tradition or archaeological evidence and creates conditions where indigenous groups are sometimes forced to support an essentialized portrayal of their own history and cultural practices in order to meet the expectations of federal officials (Daehnke 2007; Ferguson 2004; Liebmann 2008b; B. G. Miller 2003; M. E. Miller 2004; Mrozowski et al. 2009; Raibmon 2005; Wilcox 2009). Indigenous rights more generally hinge on efforts to have governments recognize and acknowledge claims to lands and resources based on their deep historical, cultural, and religious connection to their former homelands. One of the more pernicious facets of the conflict surrounding governmental recognition and indigenous rights is the view, reinforced by both anthropological and archaeological research, that these groups were essentially frozen in time, culturally unchanging as if they remained in the same state their ancestors had been for thousands of years (Ferguson 2004; Liebmann 2008b; Lomawaima 1989; Mills 2008; see Gould, this volume).

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAG-PRA) is one specific instance in which indigenous groups are forced to embrace a form of strategic essentialism to demonstrate the shared cultural relationship demanded by the law. The essentialism that underlies many of the issues surrounding NAGPRA (Gosden 2001; Liebmann 2008b; Lovis et al. 2004; Trope and Echo-Hawk 2000) and federal recognition in the United States (Daehnke 2007; B. G. Miller 2003; M. E. Miller 2004; Mrozowski et al. 2009; Raibmon 2005) is reinforced by the false dichotomy between history and prehistory. In practice such a distinction promotes the separation of what would otherwise be viewed as a continuous history whose unfolding is characterized by periods of both change and continuity. The result is a view of the Native American past as a deep, often static prehistory truncated by European colonization. History is equated with the arrival of Europeans and the adoption of European technologies and religion that resulted in an overall loss of cultural authenticity when compared with a more essentialized perception of the prehistoric past (Silliman 2009).

Many scholars informed by postcolonial theory view essentialism, strategic or otherwise, as untenable, leaving them to question the underlying legitimacy of NAGPRA and its avowed goals (see Liebmann 2008b; Lovis et al. 2004). Instead, these scholars argue for a constructivist view of identity formation in which changes resulting from colonial entanglements are not viewed as resulting in a loss of cultural authenticity (see Gosden 2001).

In light of this, some scholars, most notably Liebmann (2008b; but see also Trope and Echo-Hawk 2000) have argued for a ‘third way’ open to both indigenous groups and archaeologists who are struggling with legal issues surrounding the demonstration of cultural affiliation in which the choice ‘is neither rigidly essentialist nor radically constructivist’ (Liebmann 2008b: 83), and this is the concept of hybridity as outlined by Bhabha (1994). As employed by many postcolonial theorists, however, hybridity is too often viewed synchronically and does not incorporate the importance of history in shaping identity. A more sophisticated understanding of both hybridity and, by extension, identity is therefore dependent on a conceptualization of time that is not artificially divided between history and prehistory—a dichotomy that represents a barrier to this more historically contingent view of cultural identity.

In an effort to counter a dichotomized view of Native American history and to provide the temporal depth often ignored in discussions emphasizing synchronic aspects of hybridity, I provide an example that illustrates the importance of drawing connections between the present, recent past, and deeper history. I draw on research from Magunkaquog and Hassanamesit, two ‘Christian Indian’ communities in Massachusetts, to explore the intellectual confines imposed by the false distinction between history and prehistory. By focusing on these two historic communities, I will provide evidence that links religious and cultural practices to a deeper past, demonstrating that Nipmuc cultural practices involve elements of deep antiquity and continuous change. Rather than a picture of a static society upended by European colonization, the portrait that emerges is one of spiritual continuity in the midst of rapid material change that often involved innovative ways of incorporating European technologies without the loss of cultural identity.

This research has developed through collaboration between the Fiske Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts-

Boston and the Nipmuc Tribal Nation. Rae Gould serves as the tribe’s cultural resources officer and provides her perspective on the issue (Gould, this volume). I reference some of her research and make explicit its connections to similar work carried out by the students, faculty, and staff of the Fiske Center and the Department of Anthropology over the past decade.

11.2 MAGUNKAQUOG AND HASSANAMISET

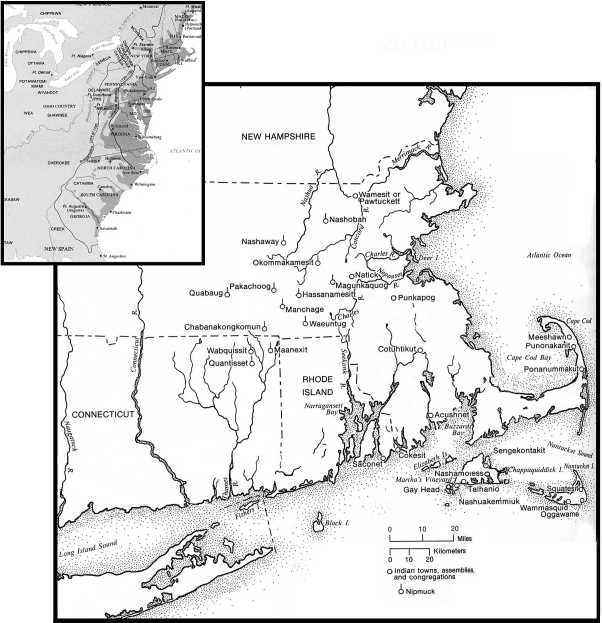

Much of the research I discuss focuses on the Nipmuc communities of Hassanamiset and Magunkaquog, that were two of what were originally fourteen such settlements incorporated into the English missionary John Eliot’s attempts to Christianize the native peoples of southern New England during the seventeenth century. The first such community, Natick, was established in 1650, followed by Hassanamesit a few years later. Magunkaquog, the seventh such community, was established by 1669 (Fig. 11.1).

Each ofthese communities was different, yet all shared a connection to Eliot’s larger enterprise of converting native peoples to Christianity. Eliot had a particular vision of religious conversion that was part of an eschatology that held that the conversion of all non-Christian believers would happen during the latter stages of the seventeenth century (Cogley 1999: 9-22). This process was to follow a particular path, with Jews and Muslims converting first. Like many religious figures of this period, Eliot was not sure where the native peoples of North America fit into this larger scheme. Therefore, he chose a particular path for their conversion that began with their adopting the cultural practices of the English. This was the primary purpose of what would come to be called the ‘Praying Indian’ communities of Massachusetts and Connecticut. The outbreak of war in 1675 between the native peoples of southern New England and the English, commonly known as King Philip’s War, temporarily put a halt to Eliot’s work. Once the war ended in 1676, he returned to working with such communities. Eventually, he helped Christianize a total of fourteen settlements; however most of the original seven communities had their daily lives severely disrupted by the war. Magunkaguog, which never had been much larger than fifty or sixty people, did not regain its pre-war vitality, although it seems to have remained viable until the middle of the eighteenth century.

Fig. 11.1. Christian Indian communities in Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies (Source: Conkey etal. 1978)

At the conclusion of King Philip’s War, the English governments of both the Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies moved to limit the remaining Native American communities from controlling their own destinies. Most importantly, they passed laws that established boards of overseers for each Native American community with responsibilities to handle the legal and commercial affairs of the various groups and then dole out the proceeds of land sales and other economic activities to the native inhabitants. Both Magunkaquog and Hassanamesit worked with overseers, but there is little in the documentary record concerning Magunkaquog before the eventual takeover of the community’s lands by Harvard College—today Harvard University. Harvard leased some of this land to English settlers to provide the college with income. The archaeological discovery of what I believe to have been the meeting house/fair house at Magunkaquog—the community did not have a church as was the case at both Natick and Hassanamesit—suggests that some of the community’s residents remained on the land after this purchase (Mrozowski et al. 2005, 2009).

One of the overarching goals of our work at both Magunkaquog and Hassanamesit is to have archaeology address concerns of the contemporary Nipmuc community. Chief among these have been the difficulties the Nipmuc have faced in their struggle for tribal recognition, a process that remains ‘controversial and contested terrain’ (M. E. Miller 2004: 3; see also Adams 2004; Daehnke 2007; B. G. Miller 2003). Consequently, the project has pursued questions that aid the political struggles of the Nipmuc while maintaining a commitment to archaeological rigour. There are some (e. g., McGhee 2008,2010) who believe that using archaeology in the service of legal or political ends is antithetical to the goals of a scientifically rigorous discipline (but see Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al 2010; Silliman 2010; Wilcox 2010). I do not accept this premise and believe that archaeology can provide information that can help the Nipmuc demonstrate the level of cultural and political continuity necessary to warrant recognition by the US government as a tribal entity (Adams 2004). Of course this would require the Bureau of Indian Affairs to alter its current policies and accept archaeological evidence as the kind of ‘new information’ it deems necessary to reopen a federal recognition petition that has been rejected.

In constructing an alternative, deeper history of the Magunkaquog community, the goal is to uncover evidence of Nipmuc political and cultural life over the past 400 years that replaces an essentialized view of that history with a picture of a more hybridized reality (Mrozowski et al. 2005, 2009; see also Gould, this volume). Here I examine a related, but different question concerning an even deeper time frame, that of Nipmuc religious life over the past 4,000 years.

11.3 MAGUNKAQUOG

In 1674, one year before the outbreak of the conflict that native groups called Metacomet’s uprising and the English referred to as King Philip’s War (1675-6), Daniel Gookin wrote a series of descriptions of the seven Christian Indian communities that English missionary John Eliot helped establish (Gookin 1970 [1674]). Gookin mostly described the larger settlements such as Natick and Hassanamesit, but he provided detail about every settlement. Documents such as Gookin’s descriptions of the Christian Indian communities were used mainly to argue for continuing support from Eliot’s financial backers in England. To assess the historical veracity of Gookin’s accounts, they must be compared with empirical evidence collected from archaeological sites.

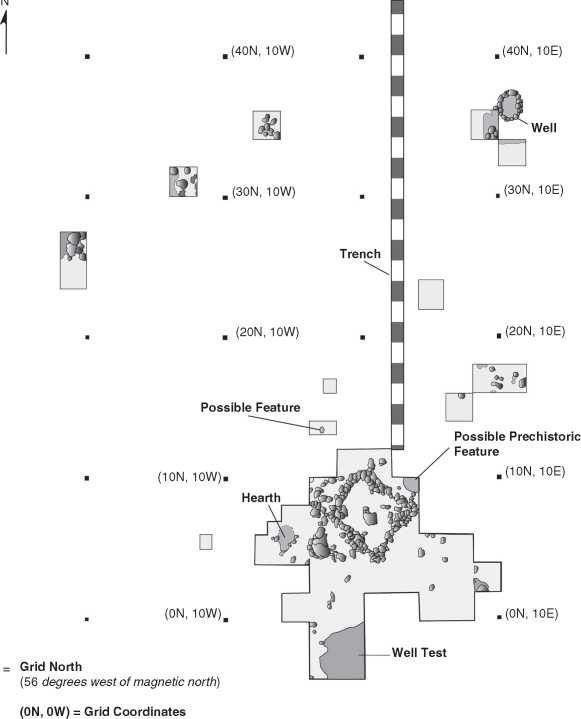

Prior to the archaeological discoveries made on what is today called Magunco Hill in Ashland, Massachusetts, by the Public Archaeology Laboratory (Herbster and Garmen 1996), no material evidence of the actual Praying Indian settlements had ever been uncovered. Burial grounds associated with three of the settlements, Natick, Punkapoag, and Okommakamesit, have been found over the past 100 years in a variety of ways. The Natick burials were encountered as part of public utility work, the Okommakamesit graves were excavated by avocational archaeologists, and the Punkapoag burials were encountered during road construction and subsequently excavated by a team of archaeologists from the Massachusetts Historical Commission and the University of Massachusetts-Boston (Kelley 1999; Mrozowski 2009; Simon 1990). The excavations conducted at Magunco Hill revealed the remains of a dry laid foundation that was purposely built into the hillside so that one floor of the building could be entered from the ground while a second lower room/cellar could be accessed through an opening on the southwest, downhill side of the yard (Fig. 11.2).

Excavations of the foundation and surrounding yard unearthed a rich assemblage of material culture that extended into a small yard area north of the foundation. Much of the assemblage was composed of items manufactured in Europe, primarily Britain. There is also a small, but highly significant collection of artefacts that exhibit evidence of native technology. Based on the manufacturing dates of the ceramics discovered on the site and other diagnostic artefacts, it appears to have been established sometime during the second half of the seventeenth century— documents suggest circa 1669—with occupation ending by the middle of the eighteenth century (Mrozowski et al. 2005, 2009).

There is no evidence for an interior hearth; however there was an exterior hearth that contained charred faunal remains and a substantial assemblage of lithic debitage, primarily from heated quartz cobbles. The orientation of the foundation, the specific European items recovered from inside it, and a yard area to the south of the structure (Fig. 11.2) suggest that the architectural remains are the community’s meeting house. In his initial description of Natick, Eliot referenced the ‘fair house’ at Natick as a place where valuables would have been stored (Whitfield 1834 [1652]: 138-43; a fair house referred to a weU-built, substantial structure in seventeenth-century England [Steane 2004: 50-1]).

Perspectives Arising Out of the Americas Magunco Hill

0 10 meters

Fig. 11.2. Magunco Hill site, Magunkaquog

It seems safe to assume that among those items that Eliot would have considered valuable would have been the English material culture stored in such a building. The material culture recovered from the site includes items associated with furniture such as bed curtain rings, ornamental chair tacks, and matching drawer pulls for a chest with possibly a single drawer. Harness hardware from both a saddle and bridle were also recovered as well as a discrete assemblage of eight identical thimbles.

Much of the remaining assemblage included ceramics, glassware, faunal material and lithic artefacts including several gunflints, quartz debitage, and quartz crystals (Mrozowski et al. 2005, 2009).

In his description of the fair house at Natick Gookin (1970: 41) writes:

The lower room is a large hall, which serves for a meeting house, on the Lord’s Day, and a school house, on week days. The upper room is a kind of wardrobe, where the Indians hang up their skins, and other things of value.

In the corner of this room mr. Eliot has an apartment partitioned off, with a bed and bedstead in it.

Of note here is that the structure served as a school and obviously the small partitioned chamber for Eliot when he, or Gookin, visited, which in Magunkaquog’s case, does not appear to have been very often (Mrozowski etal. 2005, 2009). In his description of Magunkaquog, Gookin (1970: 78-9) states that the community consists of:

About eleven families, and about fifty five souls. There are, men and women, eight members of the church at Natick, and fifteen baptized persons. The quantity of land belonging to it is about three thousand acres. The Indians plant upon a great hill, which is very fertile. The people worship God, and keep the Sabbath, and observe civil order, as do other towns. They have a constable and other officers. Their ruler’s name is Pomhamen; a sober and active man, and pious. Their teacher is named Job; a person well accepted for piety and ability among them. Their town was the last setting of the old towns. They have plenty of corn, and keep some cattle, horses and swine, for which the place is well accommodated.

It is possible that the foundation discovered on Magunco Hill could have also served as a dwelling for either Pomhamen, or Job. Or could it have been used as a gathering place where activities such as teaching young native women how to sew—evidenced by the thimbles (Loren and Beaudry 2006: 258)—may also have taken place?

As a central place in the settlement, the meeting house would have served many purposes, but chief among them appears to be an outward expression of English ways. In some respects, one might expect that of all the locations in the settlement, this had the closest appearance to an English building. This assertion is based on the dearth of evidence for Native American structures in southern New England that used stone foundations. Instead, most native structures employed wooden support posts without foundations of any kind, potentially calling into question whether the foundation is that of a native structure. The recovery of quartz crystals purposely placed in three corners of the foundation strongly counters this assumption. These crystals were extracted from larger quartz cobbles that were heated in a hearth immediately outside the foundation. If the building on Magunco Hill served as a teaching place for the most pious of their community, the presence of the crystals suggests that the lessons here were steeped in a native spirituality of great antiquity, possibly as deep as 4,000 years ago (see below).

It is connections such as this that argue for the elimination of the practice of bounding history and prehistory as separate. The bulk of material culture recovered from the foundation may easily be interpreted as an English household. Yet the presence of quartz crystals, as well as an assemblage of quartz gunflints that Luedtke (2000) and Murphy (2002) both ascribe to native lithic traditions, reveal a more complex picture. Murphy’s analysis clearly links the quartz crystals at Magunkaquog to spiritual and religious practices in southern New England at least 4,000 years ago. The adoption of specific technologies such as metal cooking vessels and English ceramic pots by native groups throughout southern New England (see Bragdon 1996; Crosby 1988) represents actions designed to incorporate new elements into a cultural lexicon with deep, but not static, historical roots. In the minds of those adopting the technology, the goal is to maintain identity not relinquish it.

11.4 DEEPER CONNECTIONS

I believe that the quartz crystals recovered at Magunkaquog represent deeply seated indigenous spirituality. Such an interpretation is supported by evidence from a variety of earlier contexts from the region in which quartz crystals are found in association with what can best be described as religious or spiritual activities (e. g. Hoffman 2003, 2006; Murphy 2002). In southern New England, evidence for quartz crystal uses in symbolic or ritual contexts dates to at least 4,000 years ago (Hammell 1983, 1992; Hoffman 2003, 2006). Hoffman describes a site in Middle-borough, Massachusetts, dating to between 3,000 and 2,000 years ago in which quartz crystals were extracted from quartz cobbles. Hoffman (2003: 63-71, 2006: 97-100) believes that the specialized lithic tools being produced at the site were for exchange purposes. The variety of quartz in use is the same as that used by the residents of Magunkaquoag (Hoffman 2003: 67; Murphy 2002). Based on the consistent association of specific tool types in burial and other archaeological contexts thought to be linked with religious practices, Hoffman believes that the crystals themselves were being used for such purposes as early as 3,000 years ago. Precisely when quartz crystals began to be used for religious purposes is difficult to say; however, their use, especially in connection with religious practices, healing, and political action, is supported by case studies throughout the New World based upon recent and earlier archaeological research as well as a rich ethnographic and historical literature (e. g., Bray 1992; Fletcher and LaFlesche 1911; Fortune 1932; Helms 1979, 1988; Hofman 1891; Lopez Austin 1988; McGregor 1943; Parker 1913; Radin 1945; Skinner 1920; E. A. Smith 1883; Weltfish 1965; Wyman 1936).

Hammell (1983, 1992) presents a wealth of information on the use of quartz crystals among the native groups of eastern North America, but particularly as to how beads, shell, crystals, and other ‘brilliant’ objects functioned as metaphors for light in native cosmology. Hammell notes, for example, that among the native groups of northeastern North America ‘Light is a prerequisite of life. So much so that Light is not only Life, but Light is mind, Light is Knowledge, and Light is Greatest Being’ (1983: 6). These crystals are also viewed as exhibiting whiteness and, as such, often serve as metaphors for power, the heart, or the soul, and that is why they are placed in the mouth of a deceased person (Hammell 1983: 13). Hammell also describes how the ownership, ingestion, and regurgitation of crystals is common practice among medicine and doctor’s societies among the Pawnee Caddoans (Weltfish 1965), the Omaha and Winnebago Siouans (Fletcher and LaFlesche 1911; Fortune 1932; Radin 1945), the Menominee and Chippewa-Ojibwa Algonquians (Hofman 1891; Skinner 1920), the Seneca Iroquois (Parker 1913: 70) and their Southern Iroquoian kinsmen, the Tuscarora (E. A. Smith 1883: 68-9) resident among the Northern Iroquoians since the early eighteenth century (Hammell 1983: 13). Their use among these many groups varies, including divining the success ofhunting, in the process ofactually finding game animals, and the greater identification ofquartz crystals as spiritual aides for both seeing and knowing (Hammell 1983: 14).

Hammell (1992) expands both his temporal and topical focus by examining the intersection of colour, ritual, and material culture in linking the use of crystals as well as marine shell and freshwater pearls in mortuary contexts. He argues that physical boundaries such as the rims of settlements were also seen as ritual thresholds and as such places where ‘items such as crystals would be placed’ (1992: 454). He notes, for example, that the Natchez in southeastern North America incorporated spectacular crystals into the structure of their temples (Hammell 1983: 16-17). Among the Iroquois, evidence suggests the use of crystals in mortuary contexts—also as points of intersection between different worlds, life/death, during the same time frame as that suggested by Hoffman (2006), between 3,000 and 2,000 years ago. Crystals, as well as other items that were white, black, or red, were traded throughout North America (Hammell 1992: 458).

These dates are also consistent with those suggested by Brown (1997) for the growth of archaeologically recognizable religious activities in eastern North America. In assessing the evidence for religious activity among the indigenous groups of eastern North America, Brown (1997) notes that archaeologists have been surprised to find evidence of ritual continuity going back deeper than 500 years. Drawing on evidence from a variety of contexts Brown (1997: 481) argues that archaeology evidence of religious activities extends back at least 5,000 years and this includes the use of quartz crystals.

Quartz crystals have been recovered from archaeological contexts believed to be associated with religious activities across North America, Central America, and portions of South America. I have already discussed their presence in ritual contexts in eastern North America, but they have also been recovered from sites in California (Koerper et al. 2005; Pearson 2002) and the Southwest (e. g., McGregor 1943; O’Hara 2008; Wyman 1936). The evidence for their use in Mesoamerica and South America is also extensive (e. g., Brady and Prufer 1999; Gell 1998; Hanks 1990; Helms 1988; Lopez Austin 1988; Saunders 2003). Brady and Prufer (1999) and Saunders (2003) provide comprehensive reviews of archaeological and ethnographic evidence of ritual practices that include discussions of quartz crystals as well as other materials that project brilliance. Saunders (2003: 16) captures the geographic extent of such practices when he states: ‘From the Amazon to the Andes and from Lower Central America through Mesoamerica and the Caribbean to North America, different philosophies, symbolic associations, technological choices, and materials bolstered or reflected Amerindians’ desire for the aesthetic of brilliance.’ In the same vein as Hammell’s (1992) description of the native groups of eastern North America, Saunders (2003: 18) notes that ‘for Amerindians, light permeated the world, linking earth, sky, sea, and atmospheric phenomena, infusing the whole with spirituality and morality and energizing it with cosmic power’.

The association of crystals with light and power is a major reason they were used in many forms of curing and divination. Crystals were part of a larger group of objects that included metals, such as gold, whose brightness and shininess were prized for use in a variety of ritual contexts. Brady and Prufer (1999) and Saunders (2003) also provide numerous examples of crystals and other bright objects used in religious and healing practices, and being associated with places, such as caves, that also held special cosmological significance. Brady and Prufer (1999) focus on the southern Maya lowlands and the extensive evidence of crystals being used by ritual specialists. In many instances, these practices were carried out either on mountains or in caves that held particular importance for the Maya. Caves, in particular, were significant spiritually laden spaces associated with the Earth god. Brady and Prufer (1999: 131) give additional examples of groups in Central and North America that view crystals metaphorically as the hearts of religious practitioners and also believe that people’s hearts turn to crystal after death. They also note that crystals are part of curing rituals where they are moved over the body in the same way that divination is carried out. Crystals were one of the items that were produced for both spiritual use and for exchange, but they were just one of many such items including ‘Jade, shells, pearls, brightly colored ceramics, and textiles, human and animal bones, glossy animal pelts, and mercury’ (Saunders 2003: 22). What they offered those who used them was the ability to see and navigate both the everyday world and the spirit world with greater clarity. This is one reason that crystals were used to decorate Inca temples for example (Saunders 2003: 20).

As the discussion above testifies, there is strong evidence for the spiritual importance of quartz crystals throughout much of the New World. The connection of quartz with its refractive qualities with regard to light, its whiteness, and a multi-layered set of spiritual beliefs is confirmed by research that is hemispheric in scope. The geographical extent of quartz crystal use is matched by comparable evidence of its deep history. Although the dates for the early use of quartz crystals vary, there is little doubt that it was commonplace between 4,000 and 2,000 years ago, and continued after the arrival of Europeans in the New World.

The widespread use of crystals for religious purposes as well as their deep history in both time and space lend support to the interpretation that the crystals recovered from the foundation at Magunkaquog held spiritual importance even for those Native American groups who we believe were embracing some form of Christian religious practices. The apparent placement of crystals in the corners of the foundation at Magunkaquog is consistent with evidence from eastern North America of their being placed on the rims of settlements that were viewed as ‘ritual thresholds’ (Hammell 1992: 454). If Hammell is correct, then the placement of crystals within the Magunkaquog foundation is a fitting example of a continuity of practice that can be traced to traditions of considerable antiquity.

The use of quartz crystals is not the only evidence from Magunkaquog of deeper connections to the past. The lithic technology that produced the quartz and quartzite gunflints recovered from the site is also consistent with long-standing cultural practices (Luedtke 1999, 2000; Murphy 2002). Based on her analysis of the quartz gunflints from Magunkaquog and other sites in southern New England, Luedtke (1999, 2000) concluded that the technology employed in their production and use was shared by the native groups of southern New England.

In the same way that there is ample evidence for the deep history surrounding the use of quartz crystals, there is similar evidence surrounding the history of lithic technologies throughout North America (e. g., Cobb 2003; O’Dell 2003). The reuse of European glass in the production of several categories of tools by Native American societies across North America (e. g., Cobb 2003; Nassaney and Volmar 2003; Silliman 2003) is another example. In both cases, cultural practices with deep historical roots are shown to be flexible enough to accommodate new materials, such as glass, and new forms, such as gunflints, into a broader cultural topography that remained distinctly Native American. Liebmann discusses an analogous situation in which Lakota women adopted technologies that were forced on them to produce ‘star quilts’ whose design elements were similar to Wicapi Shina (star robes) made from bison hides (2008b: 83-9). These star quilts remain an important part of Lakota spiritual practices today and as such represent an important example of a hybridized cultural form that speaks to Lakota cultural vitality.

Silliman (2009) provides comparable examples from his work on the Eastern Pequot Reservation in Connecticut. Silliman notes that archaeologists have helped perpetuate the view that colonization resulted in cultural changes that marked the loss of Indian identity, especially when compared with an essentialized prehistoric baseline of unchanging continuity. Instead, he finds strong material evidence that, like the Lakota, Pequot households adopted European material culture without losing their cultural identity. Of particular importance is his argument that comparative baselines employed by archaeologists need to remain historically fluid to account for the fact that Pequot children raised in an eighteenth-century household would not view their materiality as part Pequot, part English— their use of English ceramics would be part of their own cultural patrimony. In instances such as this, it may be inappropriate to link notions of continuity to a deeper past that was itself far from static. Like Liebmann (2008b), Silliman (2009; see also Ferguson 2004; Lomawaima 1989; Mills 2008) argues for a greater emphasis on hybridized pictures of cultural change. While I agree with Silliman when he argues that archaeologists make a mistake when they assume that colonial-era indigenous groups were conscious of the way their lives differed from those of their prehistoric ancestors, there is evidence that points to hybridized cultural forms existing alongside those that are indeed linked to earlier, but not necessarily static cultural practices. Evidence of this comes from a community such as Magunkaquog, but also the Nipmuc households dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries associated with the Christian community of Hassanamesit.

11.5 HASSANAMESIT

The sale of much of Hassanamesit to white settlers in 1727 resulted in the allotment of land parcels to prominent members of the remaining Hassanamesit community in what is today Grafton, Massachusetts. One of these plots was that of Moses Printer. His property has remained in his descendants’ hands until the present day. In fact the Printer/Cisco homestead serves as the current Nipmuc Reservation in Grafton, Massachusetts. Another of the lots was that of Sarah Robbins and Peter Muckamaug. Although Muckamaug’s name appears on the 1727 map, the 106-acre parcel remained in the hands of four generations of women, reflecting the matrilineal practices of the Nipmuc. Sarah Robbins was the daughter of a prominent Nipmuc leader. Her daughter, Sarah Muck-amaug, inherited the property around 1750 and was responsible for the construction of the foundation that has been unearthed as part of our investigations. Her daughter, Sarah Burnee-Phillips added to the dwelling between 1798 and 1802. It was this house that was home to Sarah Boston Phillips who lived until 1837. Despite the fact that English law was highly patriarchal, four generations of Nipmuc women maintained a strong presence on the same piece of land for more than 125 years.

The bulk of the material culture recovered from the site is of English or European manufacture. One of the more noteworthy attributes of the site assemblage is the large number of eating utensils, serving dishes, and drinking vessels—many more than are normally found on Anglo sites— that suggests the household served as a community gathering place for the local Hassanamisco (Law 2008; Law et al. 2008; Pezzarrossi et al. 2012). One notable exception to a materiality consistent with an Anglo, middle-class household is the remains of a soapstone crucible or small bowl (Fig. 11.3). The bowl fragments were recovered from a midden that contained European ceramics and other material culture including metals that date to the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century. Precisely how the bowl may have functioned is unclear. XRF analysis did reveal

Fig. 11.3. Small soapstone bowl from Sarah Boston farmstead, Grafton, Massachusetts

Evidence of both copper and zinc, but these results remain inconclusive because it is unclear whether this relates to its use—possibly in the melting of buttons or other items—or whether the metal traces reflect the context in which the bowl was recovered, or whether the metal traces derive from the original soapstone geological deposit. Analysis of soapstone quarries in Rhode Island and Massachusetts that is currently being conducted should provide evidence of the bowl’s source.

In addition to these issues the presence of soapstone raises several questions. Is this an example of an item found by one of the residents of the household that was being kept because it represented some conscious link to the past? Or was it an old technology that was understood as such, but which was employed for some new purpose such as the heating of metals. Because the bowl is small in size I am assuming that it was not used for general cooking purposes unless it involved something like a sauce or possibly for something for medicinal purposes. In either case its presence in a Nipmuc household of the eighteenth/nineteenth century represents a connection to a deeper past in which soapstone vessels were important parts of foodways practices (Hart et al. 2008; Sassaman 2010). It also reinforces the notion that colonial expansion into the New World brought with it opportunities for the combining of technologies. Rather than view the adoption of European technologies by Native Americans

As a loss of identity, more recent research points to instances of the merging of technologies as evidence of the innovative character of indigenous populations throughout the New World (e. g. Cornell and Stenborg 2003; Hayes 2013; Lowawaima 1989; Mills 2008).

Is it possible that there is a deeper dimension to the use of soapstone by the residents of Hassanamesit? One possible answer emerges when the confines of time and space, history and prehistory are transcended in search of deeper explanations. Soapstone is found on Native American sites throughout much of eastern North America and is often viewed as precursor to the development of ceramics as food cooking vessels (e. g., Custer 1988; Hart etal. 2008; Klein 1997; Sassaman 1993, 1999; B. D. Smith 1986; Truncer 2004). The use of soapstone was once linked to the hypothesized movement of groups migrating from the southeast to the Middle Atlantic and northeastern regions of North America (Ritchie 1965; Witthoft 1953). Sassaman (1999: 77-92, 2010: 201-204) notes that over time the connection between the presumed migrations and the use of soapstone has proven untenable, but that archaeologists still assumed that its use was made obsolete by the development of ceramics (e. g., Custer 1984, 1989).

More recent research has demonstrated that early soapstone mining and use unfolded across the northeast between approximately 3900 and 3550 bp (Sassaman 2010: 202). The mining of soapstone from local sources in Massachusetts and Rhode Island and its trade over long distances across eastern North America is a complex history that has only recently begun to be untangled (e. g. Hart et al. 2008; Sassaman 1999, 2010; Truncer etal. 1998). Of relevance here is a history of soapstone mining and use peaking circa 3200 bp, followed by a drop-off of use and a resurgence in popularity in mortuary contexts in both the Gulf Coastal Plain and southern New England between 2700 and 2500 bc (Sassaman 1999: 83-93). This resurgence does not appear to be linked to availability or accessibility or purely developmental factors but is instead ‘the result of conscious efforts to perpetuate exchange alliances between groups’ (Sassaman 1999: 94, 2010: 201-4). Citing Hudson and Blackburn (1983), Sassaman (1999: 94) notes that the California Chumash rejected Western cooking practices and its technology in part to maintain trade relations with native groups living on the Channel Islands. He believes that the choice of soapstone or ceramic use may be related to issues surrounding the construction and maintenance of identity, especially on the part of indigenous women (Sassaman 1993,1999: 91). If Sassaman (1999: 91; see also Sassaman 2010: 201-4) is correct in suggesting that soapstone use among Native American women in both southern New England and the Gulf Coast Plain was prolonged because of its role in identity maintenance then similar motives may have been behind the continuing use of soapstone by the Nipmuc women at Hassanamesit such as Sarah Burnee and her daughter Sarah Boston. Interpretations such as these are part of an emerging paradigm among archaeologists working in eastern North America whose interest in historical explanations rather than processual explanations may be setting the stage for an end to the notion of prehistory (e. g., Pauketat 2010; Sassaman 2010).

11.6 CONCLUSION

Drawing potential connections between the cultural practices of historic period Native Americans and those associated with a more distant past is just one benefit of ending the false dichotomy between history and prehistory. The use of quartz crystals and lithic technologies at Magun-kaquog and the use of soapstone at Hassanamesit are just a few examples of the material connections between the recent and deep pasts. In the case of Magunkaquog, the presence of crystals in association with the foundation offers a wide range of interpretative possibilities. If this was indeed the residence or teaching place of the community’s leader, then the presence of crystals is consistent with other examples from the New World in which they are associated with religious figures, healers, and political leaders. The soapstone crucible fragments recovered from the Sarah Burnee/Sarah Boston homestead at Hassanamesit may be equally significant. As Sassaman (1999: 91, 2010: 201-4) notes, the resurgence in popularity of soapstone during the period between 2700 and 2500 years ago may have been due to symbolic importance as evidenced by its association with mortuary practices. If the Nipmuc women at Hassana-mesit also prized soapstone because of its spiritual connections to a deeper past then it may have played a role in the homestead of Sarah Boston serving as a gathering place for the Hassanamisco Nipmuc, as Law (2008) has suggested. This interpretation is supported by recently completed analyses of faunal material from both foundation and yard deposits at the Sarah Boston farmstead. They suggest that the yard served as an area where large meals were prepared and served, possibly for community events (Allard 2010; Pezzarossi et al. 2012).

The possibility that the Sarah Burnee/Sarah Boston farmstead could have served as a community gathering place for the Hassanamisco Nipmuc during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is bolstered by recently completed research at another Nipmuc homestead established as a result of the same 1727 land redistribution as the Sarah Boston homestead. Rae Gould’s (2010) study of the Moses Printer family and their property in Grafton, Massachusetts, paints a picture similar to that of the Robbins/Muckamaug/Burnee/Boston homestead, with one important difference. Gould’s research indicates that the Printer property emerged as a gathering place of the local Nipmuc during the latter stages of the nineteenth century, very close to the period when the Sarah Boston site was falling out of year-round use. The Printer homestead remained the centre of Nipmuc life in the area throughout the twentieth century, during which time the remaining 4.5-acre parcel was officially recognized as the Nipmuc Reservation. Although this action was taken by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts it failed to aid the Nipmuc in their quest for federal recognition because of their inability to provide written evidence of political continuity (Adams 2004). At the time of the decision, the results of the archaeological research at both the Sarah Boston and Printer homesteads had not yet been initiated. Working with Nipmuc Tribal Council, the hope is that this new information may be able to support an appeal for the case to be reopened.

In seeking connections between cultural practices during the eighteenth century and those of 4,000 years ago, I have been concerned primarily with tracing the way history has unfolded in both past and present. As both Silliman (2009) and Liebmann (2008b) note, this process is not the essentialized abstraction that many scholars employ. History unfolds along a variety of paths, at varying rates, and is never the bounded, analytical reality that some would suggest; the past is not dead, it lives on and is reproduced on a daily basis. The examples of crystal use for religious purposes across North America and the New World more generally remind us that colonial perceptions of indigenous peoples as tribal polities may belie a deeper, cultural reality of a more widely shared past than our present understanding would have us believe. Rather than the image of small, culturally and spatially isolated groups of tribal peoples, the evidence of widespread religious commonalities could represent a deeper spiritual landscape that reflects thousands of years of continuity and change. This deeper, geographically larger past is part of a reality connected to today’s political landscape that is an undeniable part of archaeology’s future. The unfolding of history in the New World continues, therefore our work as archaeologists cannot be divorced from issues of contemporary social and political relevance. Federal acknowledgement in the United States is based on a foundational belief in written history and the sanctity of the written word and its links to Western legal tradition. Why should such evidence be privileged over archaeological evidence for societies that are both steeped in tradition and adaptive enough to accept new technologies? This is precisely the picture that emerges from the archaeology of communities such as Magunkaquog and Hassanamesit. Despite European colonization, there is no evidence to suggest that societies such as the Nipmuc lost their identity. In fact, the evidence points in the opposite direction, suggesting societies willing to accept new technologies and cultural practices. The crystals from Magunkaquog appear to have been used in a manner consistent with spiritual practices of great historical depth and hemispheric in scope. In this regard, there is an unmistakable flaw in the logic of federal procedures that insist that native groups seeking recognition provide written evidence of political continuity and cultural authenticity (Daehnke 2007; Den Ouden 2005; B. G. Miller 2003; M. E. Miller 2004; Raibmon 2005).

Nipmuc desire for federal recognition is a struggle to untangle history without the benefit of evidence—oral tradition and materiality—that confirms a picture of deep cultural continuity set against dynamic change and the adaptive quality of indigenous societies throughout their histories. The evidence used to argue for a loss of indigenous authenticity— elements of modernity—runs counter to that provided by long-held religious and spiritual beliefs. The central problem with the idea of prehistory vis-a-vis the Nipmuc and other native groups in parallel settings is that it acts as a barrier to both collaboration and the search for a deeper history that unveils the depth of indigenous culture. Given that the federal recognition process privileges the written word over materiality, it effectively privileges history over ancient history before Europeans and fails to accept any connection between the present, the recent past, and a deeper past demonstrated through archaeology. To deny history is to deny the very existence of a people. As archaeologists, we need to jettison these vestiges of colonialism and focus instead on breaking down barriers that deny historical process and thus can no longer be accepted. That is where the future points and we should heed its calling.

World History

World History