The Gravettian and Magdalenien were big game hunters, who perfected mass killings of mammoth, horse, and deer. But apart from the piles of bones at the kill sites there is no way we can reconstruct their hunting techniques and ritual practices. For that reason, the survival of the Plains Indians into the nineteenth century, in combination with ethnographic and archaeological evidence, gives us at least a partial insight into ancient times.

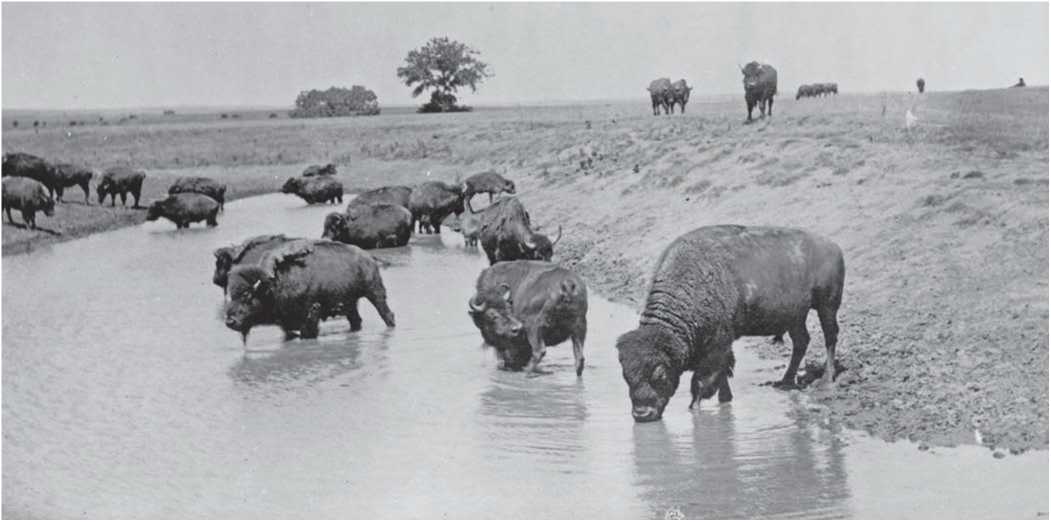

One way of hunting was during the winter. Small hunting bands of Shoshone, using snowshoes, are known to have chased bison into deep snow, where they could be easily killed with bow and arrow.31 But on the open plains the story is different. The bison are large and fiercely protective (Figure 4.30). They move in tight-knit herds, making it difficult to separate calves or females. Not only are the massive animals surprisingly agile, they also have amazing endurance when chased. To get them to run off a cliff was, therefore, a complex affair that required a carefully orchestrated plan to lure the animals calmly into gathering basins and then when the moment was right to raise a shout and drive them into lanes. Weeks of preparation were needed. Once the animals were correctly positioned, runners would charge along with them into the lanes toward the cliff. It was dangerous for the runners as well as for the team lining the lanes and trying to direct the traffic. If there was a mistake and the herd stampeded in the wrong direction, it could take days to calm the animals and begin the process again. A successful cliff stampede required hundreds of people brought together from a vast region.

47 29 11 N, 111 32 W 49 42 09 N, 113 39 23 W

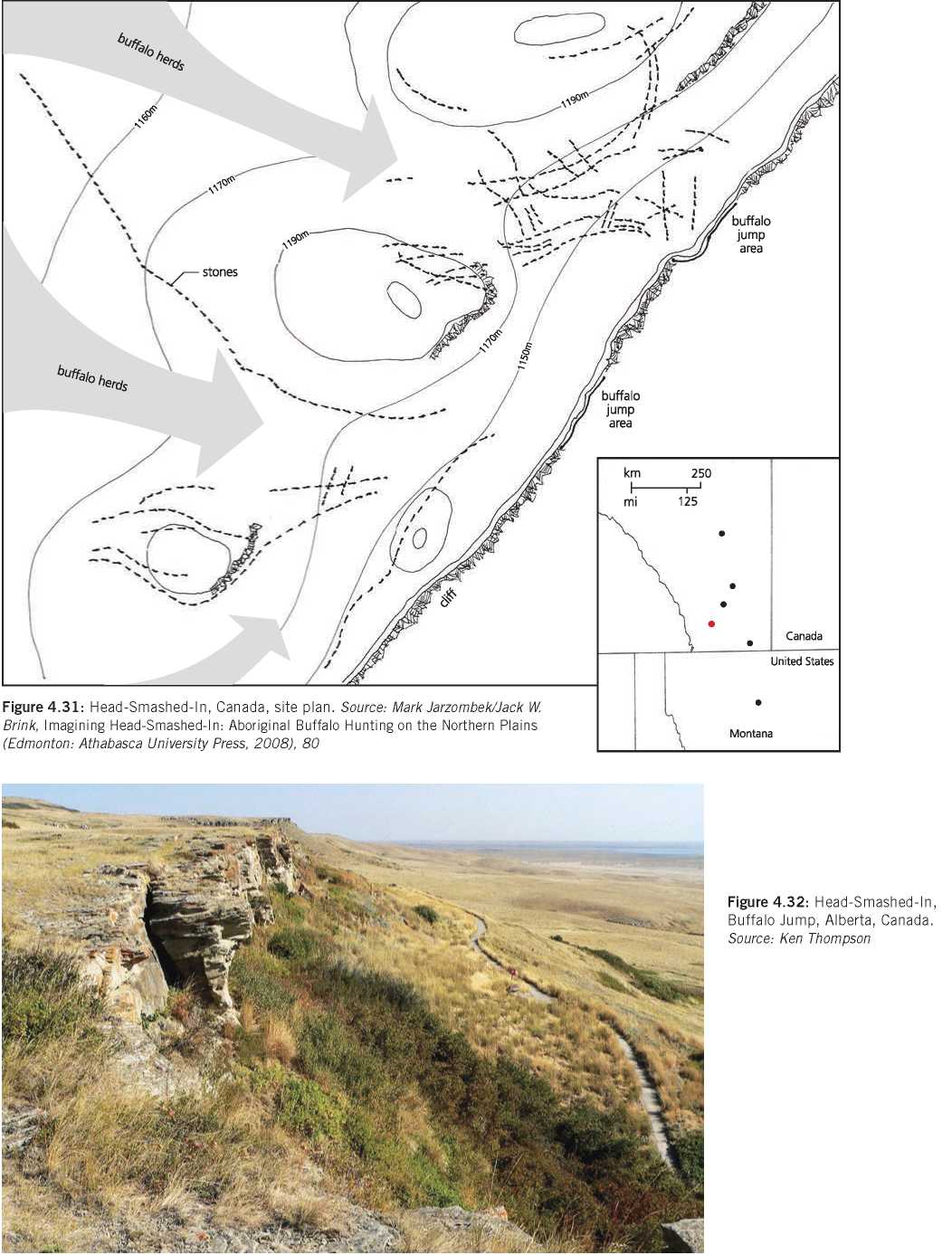

Among the numerous cliff jumps there is Bonfire Shelter in Texas, which was used for an extended period of time beginning around 8000 bce.32 Another was the Madison Jump in Montana, and to the north, in southwest Alberta, Canada, there is the Head-Smashed-In Cliff, which has at its base a 10-meter-deep pile of animal bones33 (Figures 4.31 and 4.32). With its rolling hills and open prairie, the area was ideal for both the bison and their hunters. The rivers and grass provided food for the animals, but the hills allowed humans to spy on their prey without being noticed. Just to the west of the cliffs there were several natural mounds that served as excellent places to hide. The buffalo were chased between the mounds and as they accelerated through they would not have had time to react before stumbling over the cliff edge. The men made rows of rocks to define their positions during this hectic event.

Figure 4.30: Buffalo, Wyoming, USA. Photographed in 1905. Source: Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-136258

Processing the animals was time-consuming. Hides were made into clothing, blankets, and tipi covers. Intestines were dried and then stuffed with meat and roasted over coals. But what made the bison so important was body fat. Fat, not meat, was the primary food source most sought after by the Plains Indians. Other animals like the moose were easier to catch, but were leaner and thus less valued. The pieces of fat were removed and rendered into lard. Drying fat and meat not only reduced their weight, but added to their longevity. Meat spoils because of bacteria taking hold in the moisture. Without moisture, beef and fat can last a considerable time. Dried meat, however, is not particularly tasty and without fat has actually little nutritional value. To compensate, the cooks made something called pemmican. The word comes from the Cree and is derived from the word pimt, meaning “fat, grease.” It is prepared by taking the dried meat and pounding it a powder-like consistency that is then mixed with fat and dried fruits such as saskatoon berries, cranberries, blueberries, or choke cherries. The result is then placed in rawhide pouches and is an ideal nutritional package for long hunting trips.34 Pemmican was an important staple in the Indian diet and was made for thousands of years on the plains.

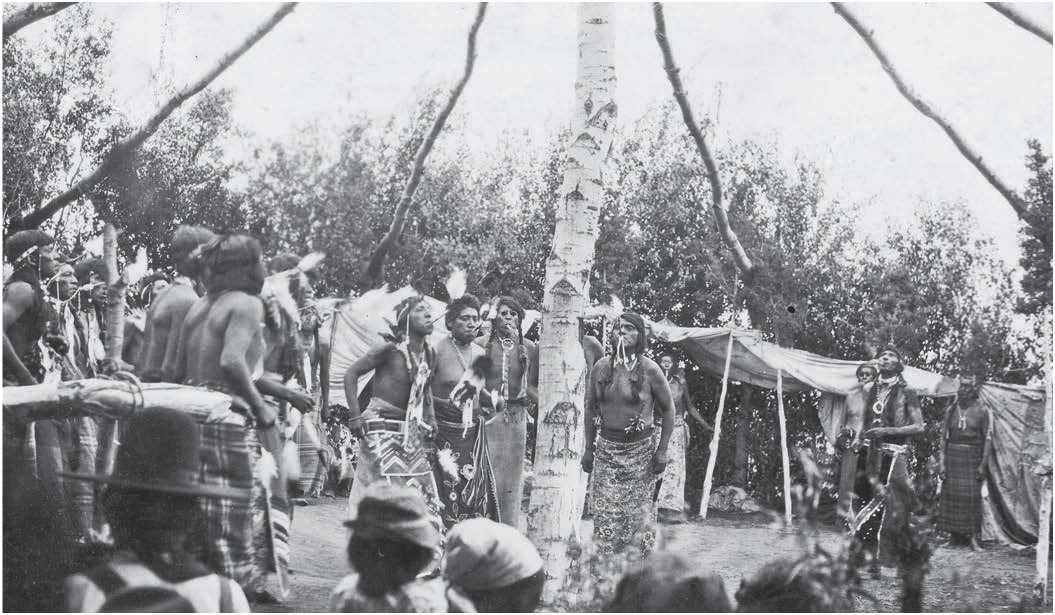

Given their centrality to the Plains Indians, it stands to reason that bison were associated with ritual celebrations, dances and feasts, and ceremonial events, the most important of which was the Sun Dance. Though it was practiced differently by several North American Indians, it had the intention of proving the continuity between life and death and between human and animal. Usually held once a year at the time of the summer solstice, the dance could last from four to eight days. The events were run by a priest who instructed the participants in building a preparatory tipi.35

Although the practice was banned by the United States government in the 1880s, photographs and ethnographic evidence give us a good picture of the event. It takes place inside a special circular structure made by men known for their eminence in the tribe (Figure 4.33). They identify a tree with a fork in the top that will become the center pole of the lodge. The notch represents the eagle’s nest. The eagle flying close to the sun is the link between men and the spirit world. Before raising the sun-pole, a fresh buffalo head with a broad center

Figure 4.33: Shoshone Sun Dance, Fort Hall Reservation, Idaho, 1925. Source: U. S. National Archives and Records Administration, No. 298649

Strip of the back of the hide and tail was fastened with throngs to the notch. The tree with the buffalo head facing the setting sun represents the center of the world, connecting the heavens to the earth. A medicine man may use the pole as a source of energy, touching his eagle feather to it and then touching the patient. The pole is festooned with sweetgrass that represents communication with the spirit world. Poles are placed against the top of the pole in a radiating fashion. Its east edge is considered the entrance and there is a fireplace between the entrance and the sacred pole, with the chief’s position being to the west of the pole facing the entrance.

The dance is a type of contest between man and animal. The warriors must show courage and stand up to the buffalo before the buffalo finds him worthy. The dancer has to learn to see through the buffalo’s eyes and become one with it. Making the buffalo sacred, symbolically giving new life to it, and treating it with respect and reverence acts as a sort of reconciliation. Without the buffalo there would be death, and the Plains Indians saw that the buffalo not only provided them with physical well-being, but kept their souls alive, too. They believed that the buffaloes gave themselves to the humans for food. The sacrifice of the dancers through fasting, thirst, and self-inflicted pain reflects the desire to return something of themselves to nature. At the end of the ceremony, the dancers are laid on beds of sage to continue fasting and to recite their visions to the priest. These visions may hold new songs, new dance steps, or even prophecies of the future.

World History

World History