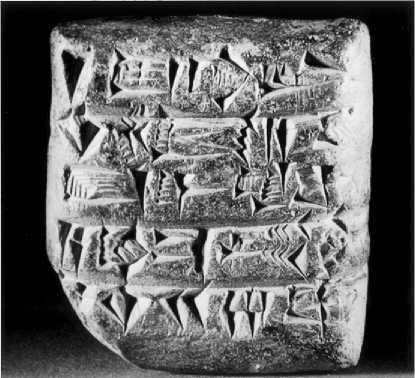

The word ‘cuneiform’ derives from the Latin word cuneus, meaning ‘wedge’. It refers to the wedge - or nail-shaped signs of the Mesopotamian script after the adoption of a blunt reed stylus about 2800 BC. (Figure 7) In order to write faster, the scribes exchanged the previous prismatic stylus for one with a triangular end that could be rotated quickly between the fingers to impress strokes in 8 different positions. In time, the cuneiform signs became more and more simplified. The sign for sheep and that for an arrow head were reduced to a few strokes that no longer looked like the original token or pictograph they derived from. Philologists generally advocate that the cuneiform

Figure 7 Cuneiform economic tablet, from Drehem.

Signs became rotated 90° counter-clockwise early in the third millennium BC, but the fact that the script on the monumental inscriptions always remained vertical does not support this assumption.

The scribes strived to enter more and more information on the clay tablets by covering all the faces of a tablet; the obverse, reverse and sometimes even spilling along the edges. Writing on the reverse meant turning the tablet on the side (like the page of a book) or more frequently rotating the tablet over the lower edge. The economic tablets became partitioned into multiple cases, each dealing with a separate transaction and long texts were divided into horizontal or vertical columns. No punctuation was used and neither was there any division between words. After a short phase when writing was entered boustrophedon, that is, alternately reversing course at each line, the direction of the script from left to right became standard. Tablets could be fired to ensure permanence, but in practice only the texts of royal archives were subjected to the kiln.

The Mesopotamian cuneiform script always remained a complex system which relied on a mixture of several types of signs such as logograms, determinatives and phonetic signs. Common terms such as ‘sheep’ udu, or ‘shepherd’ siba, were never spelled out, but were indicated by a logogram. Determinatives were signs placed before or after a logogram to clarify the general class of items the object belonged to. For example, a star indicated the name of deities. There were also determinatives for birds, fish, plant, trees, objects of wood, leather, and stone, rivers, towns, or countries. Finally, names were written phonetically with signs standing for sounds. The drawing of the head of a man stood for the sound LU and that of the mouth for KA; these were the sounds of the words for ‘man’ and ‘mouth’ in the Sumerian language. The syllables or words composing an individual’s name were written like a rebus. For example, the modern name Lucas, could have been written with the two signs mentioned above ‘lu - ka’. Foreign loan words like MA-NA, a measure of weight, or TAM-KAR, merchant, were also among the first words transcribed phonetically.

Polyvalence and polyphony were added difficulties in writing, reading and deciphering Mesopotamian cuneiform. Polyvalence refers to the instances when one sign bore different meanings. For example, the star-shape sign could be either the determinative for a god’s name, or it could stand for ‘An’, the sky god, as well as for ‘sky’. Moreover, signs could be used in two ways: as a logograph or as a phonetic sign. For instance, the sketch of an arrow could stand for ‘arrow’ or for the sound TI that was the sound of the word for arrow in Sumerian. This does not seem to have bothered the scribes who knew according to the context if the sign was to be read logographically or phonetically. For example, if the sign for ‘arrow’ was preceded by a numeral, it meant a number of arrows. But if the sign was preceded by a star, the determinative for ‘god’, it meant the familiar personal name ‘God is life’, because the word for ‘life’ in Sumerian was pronounced ‘ti’ the same way as that for ‘arrow’.

Polyphony refers to the many signs that had several possible phonetic values. The Sumerian agglutinative language had few verbal inflexions to be translated phonetically because each word or verb was expressed by a single syllable modified by prefixes and postfixes. For example, du, was the verb ‘to build’, i-du = ‘he builds’, nu-i-du = he did not build. Plural was indicated by adding ‘me’ to nouns. For example ab-me is translated as ‘elders’.

Literary texts were already present in the Early Dynastic III period c. 2500 BC at Fara and Abu Salabigh. But cuneiform writing reached its classical period about 2100 BC, during the rule of Gudea of Lagash, when the texts achieved an unprecedented clarity and precision of language. At the time the cuneiform script was still used predominantly to register economic transactions. But there were also lengthy cuneiform royal texts written on large hollow cylinders; literary and religious texts including hymns, incantation and prayers; lists of omens according to the observations of the livers of sacrificial sheep; private or state correspondence; lexical texts entering the corresponding signs in two or three languages, and school texts.

Writing gave great prestige to Mesopotamia and in particular to Sumer, the culture deemed to have invented the first script. Writing was therefore adopted by neighbors and conquerors such as the Akkadians, Elamites, Eblaites, Hittites, Luwians, Hurrians, and Persians. About 2330, the adaptation of the cuneiform script, created for the mostly monosyllabic Sumerian language, to the Semitic-inflected Akkadian tongue - meaning that words change forms to indicate the grammatical function, gender, number, or tense (like the Latin cases) - proved particularly awkward. The Akkadians adopted the Sumerian phonetic values while also adding their own. For example the sign for ‘hand’ could be read ‘A’, as the Sumerians did, but also ‘IDU’ ( or ‘id’, ‘ed’, ‘it’, ‘et’,) the Akkadian word for ‘hand’.

Wherever it was adopted in the ancient Near East, writing brought schools. The first Mesopotamian schools, such as that at Nippur, played an especially important role in the standardization of the script. Despite the distance that separated the various cities, all Mesopotamian student scribes were learning signs for all possible things, such as plants, utensils, geographical names or professions, from identical lists, written in the same way and even in exactly the same order. This avoided the creation of multiple local writing systems that would have complicated communication. Of course the Mesopotamian schools had only a few students. Even the Mesopotamian kings did not know how to read and write but had to rely on their scribes for their correspondence.

It is difficult to assess the rate of literacy in ancient Mesopotamia from the distribution of tablets. The houses of the elite yielded a few tablets, generally found scattered in several rooms. Archives of cuneiform texts were recovered at the sites of Girsu, Drehem, Mari and Nineveh. Formal libraries were uncovered at Umma, Sippar and Larsa. The most famous library remains that of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal at Nineveh that may have held some 5000-6000 tablets. It was sacked by the Babylonian and Mede coalition in 612 BC.

The cuneiform script stands out as a unique source of information on the ancient Near East. It portrays powerfully and vividly the values and beliefs, the myths and legends of long vanished civilizations. But starting in the first millennium BC the cuneiform script waned, challenged by alphabetic scripts. The transition was slow and incremental, for example, in the seventh century BC the Assyrian king Ashurbani-pal was dictating his edicts to two scribes. The first wrote the king’s words in Akkadian, impressing the corresponding cuneiform text with a stylus on a clay tablet. The second wrote in Aramaic, a language spoken by many subject peoples. Aramaic was an alphabetic script that was traced with a flowing hand on a papyrus scroll. The last known cuneiform clay tablets are dated to about 300 AD.

World History

World History